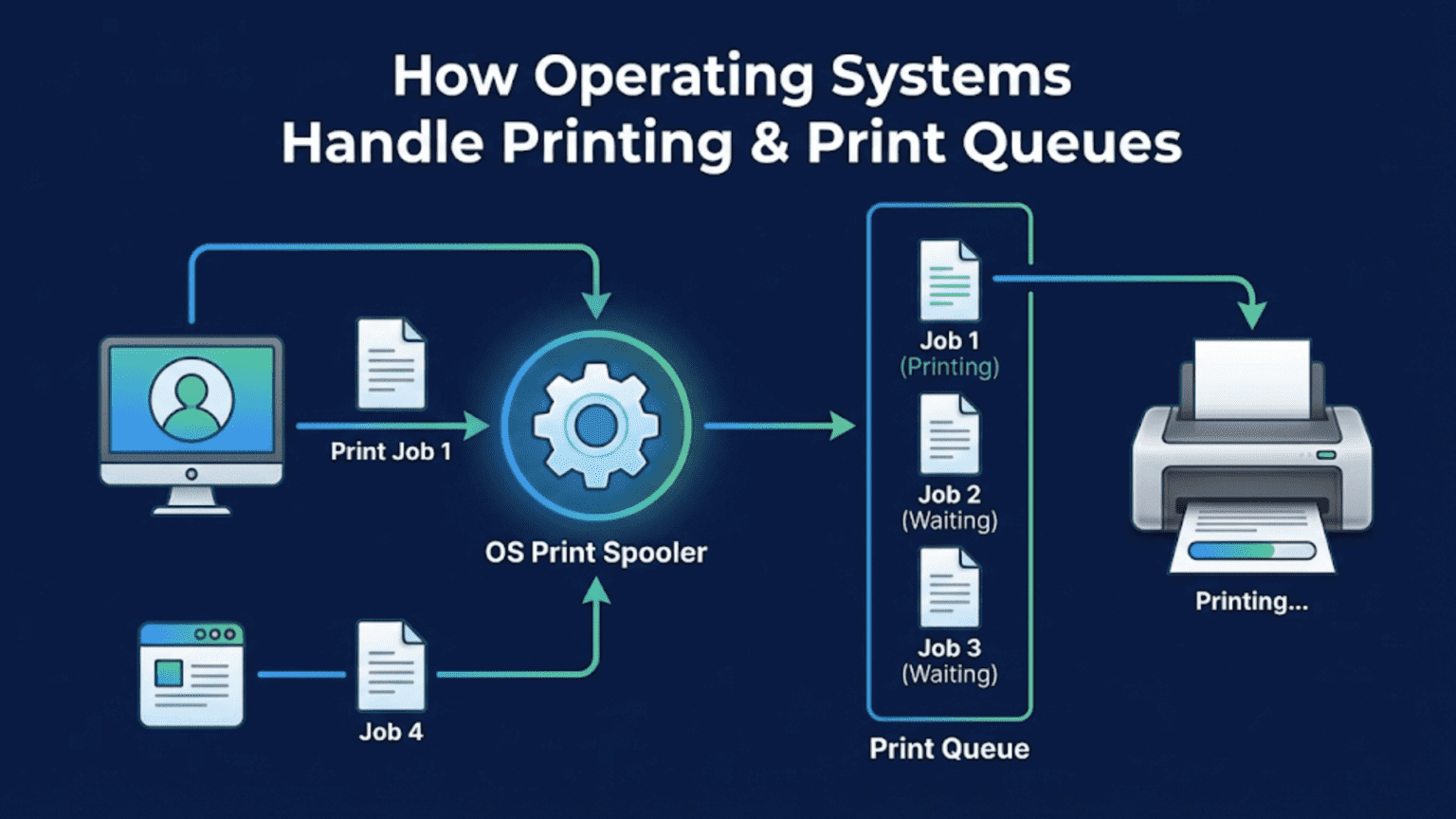

Operating systems manage printing through a print spooler—a background service that receives print jobs from applications, stores them in a queue, and sends them to printers in an orderly sequence. The print spooler translates application output into printer-specific formats using printer drivers, manages simultaneous print requests from multiple applications or users, handles printer communication, and provides status information about jobs in progress, making printing reliable and transparent to the applications requesting it.

Every time you press Ctrl+P in an application and your document begins printing, a sophisticated chain of events unfolds between your application’s print command and the physical paper emerging from the printer. Your operating system intercepts the print request, translates the document into a format the printer understands, queues it alongside any other pending print jobs, communicates with the printer hardware or network printer service, monitors the job’s progress, and handles any errors that arise—all transparently, without requiring you to understand or manage any of these details. This print management infrastructure, centered on the print spooler service and printer driver architecture, represents one of the operating system’s important peripheral management responsibilities and illustrates how OS design enables smooth hardware sharing among multiple applications and users.

Printing presents unique challenges for operating systems compared to other types of I/O. Printers are significantly slower than computers—even a fast printer produces perhaps 50 pages per minute while a computer can generate print data for hundreds of pages per second. This speed mismatch would block applications waiting for printers if the OS didn’t provide queuing. Printers are typically shared resources in office environments, with multiple users sending documents to the same printer. Printers speak proprietary languages (PCL, PostScript, various vendor-specific formats) that applications don’t understand natively. Printers fail in many ways—running out of paper or toner, experiencing paper jams, going offline—that require user notification and job management. The print spooler, driver architecture, and print queue management that operating systems implement address all these challenges, creating the reliable, manageable printing experience we rely upon daily. This guide explores how operating systems handle printing comprehensively, from the driver layer through the spooler to network printing and print management.

The Print Spooler Architecture

The print spooler is the central component of operating system print management, coordinating all aspects of printing from job receipt to completion.

The word “spool” is an acronym for Simultaneous Peripheral Operations On-Line, reflecting the original purpose of allowing applications to continue working while output spools to a peripheral device. Rather than an application waiting directly for the slow printer, it writes data to the spooler (a fast disk operation), which the spooler then feeds to the printer at the printer’s pace. This decoupling means printing an entire 100-page document takes seconds of the application’s time regardless of how long the printer takes.

On Windows, the Print Spooler runs as a system service (spoolsv.exe) that starts automatically at boot. The spooler accepts print jobs from applications via the Windows printing API, stores them as spool files in %SystemRoot%\System32\spool\PRINTERS, manages the queue for each printer, and transmits jobs to the appropriate print processor and then to the printer. The spooler also handles printer notifications, communicating status back to applications and users.

On Linux and macOS, CUPS (Common Unix Printing System) provides equivalent functionality. The cupsd daemon listens for print requests via IPP (Internet Printing Protocol) on port 631, manages printer configurations in /etc/cups/, stores spool files in /var/spool/cups/, and communicates with printers. CUPS serves as both the print spooler and the print server, handling everything from job reception to printer communication through a unified system.

The spooler maintains queue persistence across system operations. If the computer is restarted while print jobs are queued, the spooler restores the queue from spool files upon startup and resumes sending jobs to printers. This persistence ensures print jobs aren’t lost due to system reboots or spooler restarts.

Spooler isolation improves system stability by preventing printer driver problems from crashing the entire system. Windows runs printer driver rendering in a separate process (printfiltersvc.exe), so if a driver crashes while processing a print job, the spooler itself continues running and can restart the failed process. This isolation means a buggy printer driver that crashes during rendering doesn’t cause the entire print queue to fail or require system restart.

Printer Drivers and Language Translation

Printer drivers are the critical software components that translate generic print requests into printer-specific commands, enabling diverse printers to work with applications that know nothing about specific printer models.

Printer drivers perform two primary functions: rendering (converting document descriptions into raster or vector data the printer can process) and language translation (converting that data into the specific printer command language the device understands). Different printers speak different languages—HP PCL (Printer Command Language), Adobe PostScript, various proprietary vendor formats, and modern XML-based formats like XPS (XML Paper Specification).

The GDI (Graphics Device Interface) model used in Windows traditionally had applications render to GDI—Windows’ graphics abstraction layer—and printer drivers convert GDI calls to printer commands. Modern Windows uses XPS (XML Paper Specification) as an intermediate format: applications render to XPS, XPS passes through the print filter pipeline, and printer-specific filters convert XPS to the printer’s native language. This pipeline architecture allows inserting processing stages like watermarking, page reordering, or encryption between rendering and printing.

PostScript is a page description language treating printed pages as programs describing their content through drawing commands, text placement, curves, and fills. PostScript printers receive these programs and execute them to produce output, making PostScript resolution-independent and highly capable. PostScript drivers translate application content into PostScript programs. Many laser printers interpret PostScript, making it particularly common in professional and office printing.

PCL (Printer Command Language) is HP’s printer language, simpler than PostScript and interpreted as commands that control printer behavior rather than programs that describe output. PCL has evolved through multiple versions with PCL 6 (PCL XL) being the modern variant. PCL drivers translate print content into PCL commands. PCL’s widespread adoption through HP’s market dominance made it a de facto standard supported by most laser printers.

Raster printing sends bitmapped images directly to printers that don’t interpret programming languages. The driver renders each page to a full-resolution bitmap matching the printer’s resolution, then sends this bitmap as raw pixel data. Raster printing requires substantial bandwidth and processing but works with simple, inexpensive printers. Modern inkjet printers typically use raster printing with proprietary command sets.

Universal Print Drivers reduce the proliferation of device-specific drivers by providing drivers that work across entire product families or multiple manufacturers’ products. Microsoft’s Universal Print Driver, HP’s Universal Print Driver, and manufacturer-specific universal drivers use standard printer communication protocols to control printers without device-specific code, simplifying driver management especially in enterprise environments with diverse printer fleets.

IPP (Internet Printing Protocol) drivers work with IPP-capable printers directly without device-specific code. IPP is a standardized network printing protocol allowing print submission, job management, and printer status queries. IPP Everywhere (driverless printing) allows modern operating systems to communicate with IPP printers using printer-provided capabilities descriptions, eliminating traditional driver installation entirely for many modern printers.

Windows Print Queue Management

Windows provides comprehensive print queue management through both graphical and command-line interfaces.

The print queue viewer (accessible by clicking the printer icon in the taskbar notification area or through Settings > Bluetooth & devices > Printers & scanners > Open print queue) shows all pending, active, and paused jobs for a specific printer. Each entry shows document name, status (Printing, Spooling, Paused, Deleting, Error), owner, pages, size, and submission time. From this view, users can cancel specific jobs, pause and resume jobs, and reorder jobs if multiple are queued.

Job management operations include canceling (deleting a job from the queue permanently), pausing (temporarily stopping a job without deleting, resuming later), resuming (continuing a paused job), and restarting (starting a failed or paused job from the beginning). Administrators with appropriate permissions can manage all users’ print jobs on shared printers, while regular users can typically only manage their own jobs.

Printer status monitoring integrates with the spooler to provide real-time printer state information. Windows displays status messages like “Ready,” “Printing,” “Out of Paper,” “Paper Jam,” “Offline,” and “Printer Error” based on communication with the printer. Status bidirectional communication requires the printer to support status feedback (most modern printers do via USB or network protocols) and the driver to support status monitoring.

The Printers & Scanners settings page in Windows provides printer management beyond individual print queues. Here you can add printers (triggering driver installation and printer configuration), set default printers, view printer properties (paper sizes, color capabilities, printer preferences), manage printer permissions (who can print, who can manage the queue, who has full control), and configure printer sharing for other network users.

Printer permissions use Windows access control to manage who can use shared printers. Standard users have Print permission allowing them to submit and manage their own jobs. Power users or print operators may have Manage Documents permission allowing management of all jobs. Administrators have full control including Manage Printers permission to change printer configuration and settings. These permissions integrate with Windows’ standard security model.

The Windows Print Management administrative console (available on Windows Server and Windows 10/11 Pro and Enterprise) provides centralized management of multiple printers and print servers. Administrators can view all printers, monitor queue status across printers, deploy printers to users through Group Policy, and manage drivers across printer servers from a single interface. This centralized management is essential in enterprise environments with dozens or hundreds of printers.

CUPS: Linux and macOS Printing

CUPS (Common Unix Printing System), developed by Apple and now the standard on both Linux and macOS, provides a unified printing infrastructure combining print spooling, network printing, and web-based management.

CUPS uses IPP as its native protocol, treating all printers as IPP printers internally even when communicating with printers using other protocols through backend scripts. This IPP-centric architecture aligns with modern standards and enables straightforward network printing. Applications communicate with CUPS using the standard CUPS API or directly via IPP, submitting jobs to printer queues identified by URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) like ipp://localhost/printers/printername.

The CUPS web interface at http://localhost:631 provides browser-based printer management. Through this interface, administrators can add printers, modify printer settings, manage print queues, view job status, and configure CUPS server settings. This web interface works on both Linux and macOS, providing a consistent management experience.

Printer configuration in CUPS uses PPD (PostScript Printer Description) files describing printer capabilities—supported paper sizes, print quality settings, duplexing capabilities, color modes, and other options. PPD files enable applications to present appropriate print options and enable drivers to generate correct print data. Modern driverless printing reduces PPD dependence for IPP-capable printers, which provide capability information directly through IPP queries.

CUPS filters are programs that convert print data from application formats to printer-native formats. The CUPS filter chain processes print jobs through multiple filters—each converting from one format to another—before submitting to the printer backend. For example, printing a PDF might pass through: application → PDF → CUPS → pdftops filter → PostScript → pstoraster filter → raster data → driver-specific filter → printer commands. CUPS selects appropriate filter chains based on input format and printer capabilities.

Backends handle printer communication—the final step transmitting data to physical printers. CUPS includes backends for USB (directly connected printers), network protocols (LPD, IPP, HP’s JetDirect/port 9100), Bluetooth, and others. Third-party backends extend support to proprietary protocols. When printing over a network, the appropriate backend connects to the printer’s IP address and port, transmitting the processed print data.

The lpr command submits print jobs from the command line: “lpr -P PrinterName filename” sends a file to the specified printer. “lpq” displays the print queue, “lprm” removes jobs. These commands, standardized across Unix-like systems, provide scriptable print management accessible from shells and scripts.

Network Printing

Network printing extends the print management architecture to support printers shared over networks, enabling multiple computers to share printers efficiently.

Network printing protocols carry print data and commands between computers and printers. IPP (Internet Printing Protocol) is the modern standard, supporting print submission, job management, and printer status over HTTP. LPD/LPR (Line Printer Daemon/Line Printer Remote) is the older Unix standard, still widely supported. HP JetDirect (port 9100) provides a simple raw TCP printing protocol. SMB/CIFS enables Windows file and printer sharing. Each protocol has different capabilities for job management and status feedback.

Windows Printer Sharing allows one Windows computer to share its locally connected printer with other network users. The sharing computer runs the print spooler as a print server, accepting jobs from clients and managing the printer. Windows clients automatically download drivers from the print server when connecting—Point and Print simplifies client setup by eliminating manual driver installation. When a client sends a job, it is rendered on the client using the downloaded driver and submitted to the server’s spooler in a standard format.

Print servers are dedicated devices or computers managing network printers. Hardware print servers are small network devices that connect to printers via USB or parallel port and join the network via Ethernet or Wi-Fi, making non-network-capable printers network accessible. Software print servers run on computers or servers, managing queues for many network printers and providing centralized administration. Enterprise print servers using Windows Server or CUPS on Linux manage printer fleets, user quotas, and printing policies.

Cloud printing services enable printing from anywhere. Google Cloud Print (discontinued 2021) was an early cloud printing service. Microsoft Universal Print, available with Microsoft 365, allows printers to be registered in Azure and accessed from anywhere without print servers. Apple’s AirPrint standard enables iOS and macOS devices to print to compatible printers on the same network without driver installation. These cloud and standard-based approaches simplify printing in modern environments where users move between locations and use diverse devices.

Network printer discovery enables automatic printer detection. Bonjour (Apple’s mDNS/DNS-SD), WS-Discovery (Windows), and SNMP-based discovery protocols allow operating systems to automatically find printers on local networks, presenting them for easy installation without requiring manual IP address entry. When you add a printer on macOS or Windows, discovered network printers appear automatically in the list, dramatically simplifying setup.

Print Quality and Configuration

Operating systems provide mechanisms for controlling print quality, paper handling, and printer-specific features through driver interfaces and printing preferences.

Printer preferences dialogs (accessible via printer properties or the print dialog in applications) expose printer-specific options: print quality (draft, normal, best), paper type, paper size, orientation (portrait/landscape), color or black-and-white, duplex (two-sided) printing, copies count, and printer-specific features like stapling, hole-punching, or booklet printing. These preferences are stored and applied to print jobs, communicating to the driver which printer capabilities to utilize.

Per-document printing preferences can override defaults for individual print jobs. When you click the printer properties button in a print dialog, you access settings that apply only to that job rather than changing global defaults. This allows printing a draft at low quality for proofreading then printing the final version at highest quality without permanently changing settings.

Color management integrates with printing through ICC (International Color Consortium) profiles that describe color characteristics of printers and displays. The operating system’s color management system (ColorSync on macOS, Windows Color System on Windows) can apply color profiles to print jobs, converting colors from document color spaces to printer color spaces to ensure output colors match on-screen appearance as closely as the printer’s capabilities allow. This color accuracy is critical for photography, graphic design, and professional printing.

Paper size and media handling configuration tells the printer which paper tray to use, what media type is loaded, and special handling requirements. Operating systems communicate these settings through the driver to printers with multiple paper trays, enabling automatic selection of the correct tray based on requested paper size.

Print quality settings control the resolution and rendering approach. Higher quality settings increase DPI (dots per inch) and may use more sophisticated halftoning algorithms to improve detail and gradations, at the cost of slower printing and higher ink or toner consumption. Operating systems pass these quality preferences to drivers which implement them through appropriate printer commands.

Troubleshooting Print Problems

Understanding the print architecture helps diagnose and resolve common printing problems effectively.

Print queue stuck jobs are a frequent problem where jobs remain in “Deleting” state or the queue appears frozen. The standard solution involves stopping the Print Spooler service, deleting spool files from %SystemRoot%\System32\spool\PRINTERS, and restarting the Spooler service. PowerShell commands automate this: stopping the service, removing files in the spool directory, and restarting. This procedure clears corrupted or stuck spool files that prevent the queue from advancing.

Printer appears offline despite being connected occurs when the OS incorrectly reports printer status. On Windows, right-clicking the printer and selecting “See what’s printing” then checking “Printer > Use Printer Offline” toggle resolves cases where offline mode was accidentally set. Verifying network connectivity for network printers, checking USB connections for local printers, and ensuring the printer is powered on address physical connectivity issues.

Driver corruption causes print failures, garbled output, or application crashes when printing. Reinstalling the printer driver—removing the existing printer and driver from Printers & Scanners settings, then re-adding—resolves driver corruption. On Windows, using “Print Management” to remove driver packages from the driver store ensures complete driver removal before reinstallation.

Print quality problems like streaks, faded output, wrong colors, or blurry text indicate driver configuration issues, low ink or toner, printer maintenance needs, or hardware problems. Running printer diagnostic and cleaning utilities through the printer’s built-in maintenance tools (accessible through printer properties or printer software) addresses ink/toner and hardware issues. Verifying print quality settings in driver preferences addresses configuration causes.

CUPS troubleshooting on Linux uses log files at /var/log/cups/error_log for detailed error information. The CUPS web interface shows job status with error details. Testing with simple command-line printing (echo “test” | lpr) isolates application issues from system printing issues.

The Future of Printing

Printing technology and operating system print management continue evolving with new standards and capabilities.

IPP Everywhere (driverless printing) represents the future of printer connectivity. Modern printers advertise their capabilities through IPP, and operating systems like macOS, modern Linux distributions, and Windows 10/11 can discover and use these printers without installing manufacturer-specific drivers. The printer provides PDF or PWG Raster as input formats, and the OS handles all rendering. This approach simplifies printer setup dramatically—modern AirPrint-compatible or Mopria-certified printers work immediately when connected.

Universal Print from Microsoft brings enterprise print management to the cloud. Rather than relying on Windows print servers that require on-premise infrastructure, Universal Print connects printers directly to Azure, allowing users to discover and use printers from any location and device with Microsoft 365 credentials. This cloud-based approach eliminates print server management while maintaining enterprise features like access control and usage reporting.

Security improvements in printing address the long-underappreciated security risks that printers present. Modern printer management increasingly implements TLS encryption for all printer communication, certificate-based authentication, secure print release (jobs only print when the user authenticates at the printer), and comprehensive audit logging. The PrintNightmare vulnerabilities in 2021 that exploited Windows Print Spooler to achieve privilege escalation highlighted printing infrastructure as a significant security attack surface, driving renewed focus on hardening print management components.

3D printing integration into operating systems represents an emerging printing category. Windows 10 included native 3D printing support through the 3D Print API and 3D Builder application, treating 3D printers as peripherals managed through the standard printing architecture. As 3D printing becomes more mainstream, deeper OS integration for 3D print queue management, object preparation, and printer management will likely follow the path of traditional 2D printing support.

Conclusion

Operating system print management—encompassing the print spooler, driver architecture, queue management, and network printing infrastructure—transforms the complex challenge of communicating with diverse printer hardware into a consistent, reliable experience for applications and users. The print spooler’s queuing eliminates the speed mismatch between fast computers and slow printers. Driver architecture translates universal print requests into device-specific commands. Network printing protocols enable printer sharing across offices and networks. Queue management provides visibility and control over pending and active print jobs. Together, these components make printing transparent: applications request printing, the operating system handles everything else, and documents emerge from printers.

While printing might seem mundane compared to other operating system capabilities, the print subsystem’s design reflects important OS principles—hardware abstraction through drivers, service-based background processing through the spooler, multi-user resource sharing through queue management, and standardized protocols enabling interoperability. Understanding how your operating system manages printing transforms mysterious print failures into diagnosable problems and clarifies the architecture enabling something as seemingly simple as clicking Print to reliably produce physical documents across an enormous variety of printer hardware, network configurations, and application types. As printing evolves toward driverless IPP printers, cloud management, and enhanced security, these fundamental architectural patterns persist, adapted to modern technologies while maintaining the transparency and reliability that users and businesses depend upon.

Summary Table: Printing Architecture Comparison Across Operating Systems

| Aspect | Windows | macOS | Linux |

|---|---|---|---|

| Print Spooler Service | Print Spooler (spoolsv.exe) — Windows Service | CUPS (cupsd) | CUPS (cupsd) |

| Spool File Location | %SystemRoot%\System32\spool\PRINTERS\ | /var/spool/cups/ | /var/spool/cups/ |

| Printer Configuration | Settings > Bluetooth & devices > Printers & Scanners | System Settings > Printers & Scanners | CUPS web UI (localhost:631), system-settings |

| Print Architecture | GDI/XPS → Print Filter Pipeline → Driver | CUPS filter chain → Backend | CUPS filter chain → Backend |

| Printer Language Support | PCL, PostScript, XPS, raster, proprietary | PostScript, PCL, PDF, raster | PostScript, PCL, PDF, raster (via Ghostscript) |

| Driverless Printing | IPP Everywhere, Mopria (Windows 10/11) | AirPrint, IPP Everywhere (native) | IPP Everywhere, Mopria |

| Network Printing Protocol | SMB/CIFS, IPP, LPD, HP JetDirect | IPP, AirPrint (Bonjour), LPD | IPP, LPD, SMB (via Samba), HP JetDirect |

| Cloud Printing | Microsoft Universal Print (M365) | AirPrint (local network focus) | Third-party solutions |

| Print Server Role | Windows Print Server (spooler + sharing) | CUPS server mode | CUPS server mode |

| Printer Discovery | WS-Discovery, Bonjour, manual | Bonjour/mDNS, manual | Bonjour/mDNS, manual, network scan |

| Admin Tool | Print Management console (Pro/Enterprise) | CUPS web interface | CUPS web interface, system-config-printer |

| Queue CLI Management | sc stop/start spooler, PowerShell | lpq, lprm, cancel, lpstat | lpq, lprm, cancel, lpstat |

| Color Management | Windows Color System, ICC profiles | ColorSync, ICC profiles | CUPS color management, ICC profiles |

| Permission Model | Print/Manage Docs/Manage Printers (ACLs) | Admin controls sharing | CUPS access control lists |

| Troubleshoot Tool | Printer Troubleshooter, Event Viewer | Printer queue app, /var/log/cups | /var/log/cups/error_log, CUPS web UI |

Common Print Job States and Meanings:

| Status | Meaning | Common Cause | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spooling | Job being received from application | Normal — data transfer in progress | Wait |

| Printing | Job being sent to printer | Normal — active printing | Wait |

| Paused | Job manually or automatically paused | User paused, printer issue, admin policy | Resume when ready |

| Error | Job failed — printer reported error | Paper jam, offline, out of toner | Fix printer, restart job |

| Deleting | Job removal in progress | Cancellation requested | Usually resolves; restart spooler if stuck |

| Offline | Printer not communicating | Disconnected, powered off, network issue | Check printer connection and power |

| Out of Paper | Printer needs paper | Paper tray empty | Refill paper tray |

| Held | Job held for authentication or release | Secure print, quota exceeded | Authenticate at printer or check quota |

| Completed | Job finished successfully | Normal completion | Job will clear from history |