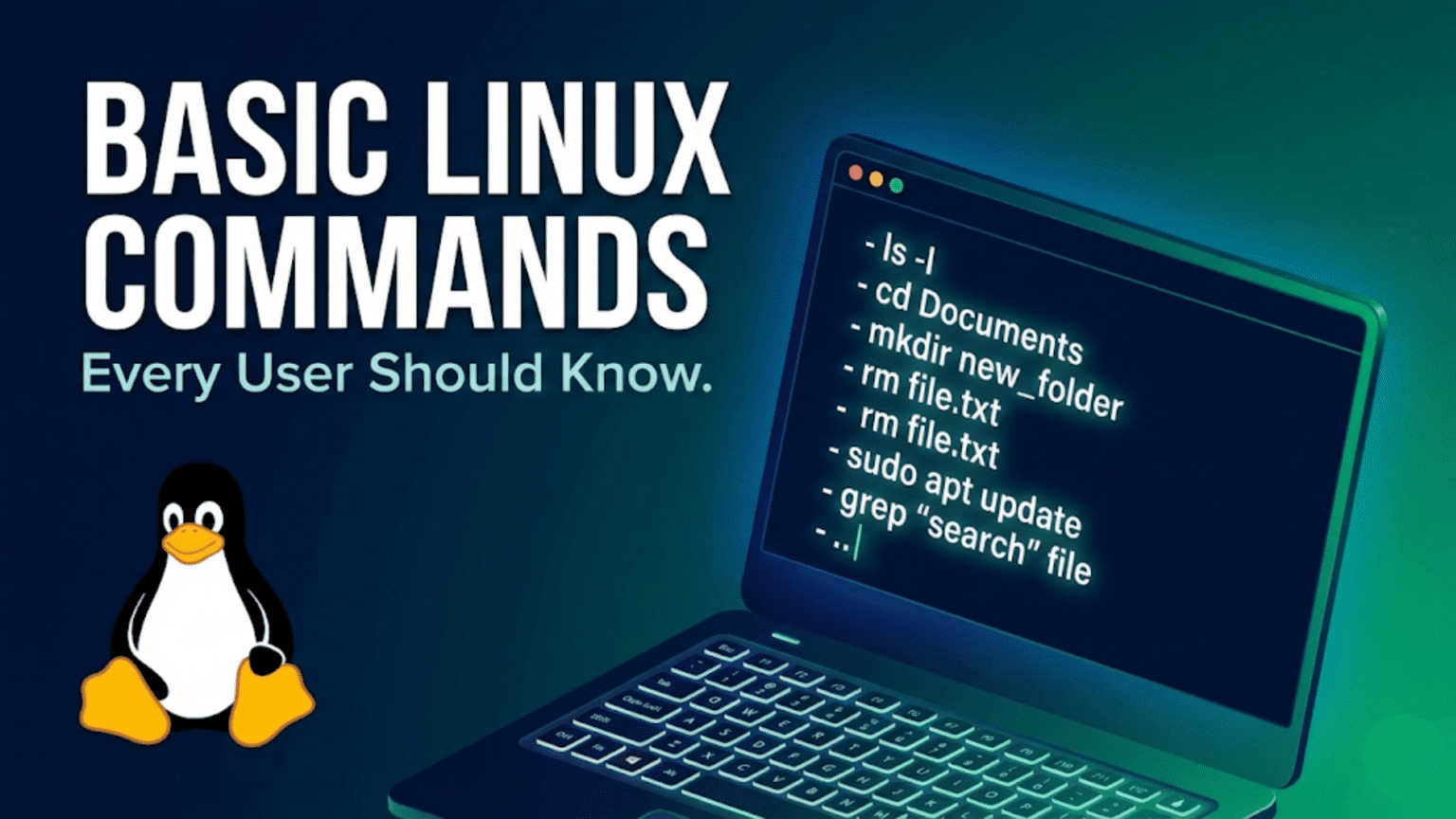

The most essential basic Linux commands fall into five categories: navigation (pwd, cd, ls), file management (cp, mv, rm, mkdir, touch), viewing file contents (cat, less, head, tail), system information (df, free, uname, whoami), and getting help (man, –help). Mastering these commands gives you the foundation to accomplish the vast majority of everyday tasks in the Linux terminal and serves as the launch pad for learning more advanced commands.

Introduction: Your First Vocabulary in a New Language

Learning the Linux terminal is similar to learning a new language. Before you can have conversations or express complex ideas, you need a basic vocabulary — a core set of words that appear constantly and form the building blocks of everything more advanced. In the Linux terminal, that vocabulary is a set of commands that experienced users type dozens or hundreds of times every day.

This article is your essential vocabulary list. It covers the commands that every Linux user needs to know, regardless of whether they are a developer, a system administrator, a student, or simply someone who wants to get the most from their Linux desktop. Each command is explained clearly with its purpose, its most useful options, and concrete examples you can run immediately on your own system.

The commands in this article are organized into logical groups based on what they do. You do not need to memorize everything at once — read through the article to understand what is available, then return to specific sections as you encounter situations that call for each command. Over time, the most useful commands will become muscle memory, and you will find yourself reaching for them automatically.

One important note before we begin: all of the commands in this article are safe for beginners. None of them will damage your system, and the few that can delete files will be clearly marked with appropriate warnings. You can try every example shown here without risk.

Before You Start: Setting Up to Practice

To follow along with this article, open a terminal on your Linux system. Press Ctrl+Alt+T to open a terminal window, or search for “Terminal” in your application menu.

When the terminal opens, you will see a prompt similar to:

username@hostname:~$The ~ symbol tells you that you are currently in your home directory. This is your starting point for everything that follows.

Category 1: Navigating the File System

Navigation commands let you move around the Linux directory structure, see where you are, and understand what is around you. These are the commands you will use most frequently — every terminal session begins with some form of navigation.

pwd — Print Working Directory

pwd tells you exactly where you are in the file system right now. It prints the full absolute path of your current directory.

$ pwd

/home/sarahUse pwd whenever you are disoriented and need to confirm your location. It is especially useful in scripts where you want to verify the current directory before performing operations.

Example:

$ cd /etc

$ pwd

/etc

$ cd ~

$ pwd

/home/sarahls — List Directory Contents

ls lists the files and directories in your current location (or any location you specify). It is one of the most frequently used commands in Linux.

$ ls

Desktop Documents Downloads Music Pictures Videosls has many useful options that change what information it shows and how it is displayed:

ls -l — long format, showing permissions, owner, size, and modification date for each item:

$ ls -l

total 48

drwxr-xr-x 2 sarah sarah 4096 Feb 10 09:22 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 5 sarah sarah 4096 Feb 17 14:31 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 3 sarah sarah 4096 Feb 18 08:15 Downloadsls -a — show all files, including hidden files that start with a dot:

$ ls -a

. .. .ba.sh_history .ba.shrc .config Desktop Documents Downloadsls -lh — long format with human-readable file sizes (KB, MB, GB instead of raw bytes):

$ ls -lh

total 48K

drwxr-xr-x 2 sarah sarah 4.0K Feb 10 09:22 Desktopls -la — combines long format and all files (the most commonly used combination):

$ ls -lals /path/.to/directory — list a specific directory without navigating to it:

$ ls /etcPro tip: ls -la is so commonly used that many Linux users create an alias ll that runs it automatically. We will cover aliases later in this series.

cd — Change Directory

cd moves you from your current directory to a different one. It is the navigation command you will use constantly.

$ cd Documents

$ pwd

/home/sarah/DocumentsEssential cd patterns:

cd ~ or just cd — return to your home directory from anywhere:

$ cd /usr/.bin

$ cd

$ pwd

/home/sarahcd .. — move up one level to the parent directory:

$ pwd

/home/sarah/Documents

$ cd ..

$ pwd

/home/sarahcd ../.. — move up two levels:

$ pwd

/home/sarah/Documents/projects

$ cd ../..

$ pwd

/home/sarahcd - — go back to the previous directory (like a browser’s back button):

$ cd /etc

$ cd /var/.log

$ cd -

/etc

$ pwd

/etccd /absolute/.path — navigate directly to any location using an absolute path:

$ cd /usr/.share/doc

$ pwd

/usr/share/docUnderstanding relative vs. absolute paths: When you type cd Documents, you are using a relative path — you are telling the shell to look for a folder called Documents in your current location. When you type cd /home/sarah/Documents, you are using an absolute path — you are specifying the complete path from the root, which works from anywhere.

Category 2: Working with Files and Directories

These commands create, copy, move, rename, and delete files and directories. They are the building blocks of all file management in the terminal.

mkdir — Make Directory

mkdir creates a new directory.

$ mkdir projects

$ ls

Desktop Documents Downloads Music Pictures projects Videosmkdir -p — create nested directories all at once, even if intermediate directories do not exist:

$ mkdir -p projects/2026/january

$ ls projects/2026/

januaryWithout -p, trying to create projects/2026/january when projects/ does not exist yet would fail. With -p, all the necessary parent directories are created automatically.

touch — Create an Empty File or Update Timestamps

touch creates a new, empty file if it does not exist. If the file already exists, it updates the file’s last-modified timestamp without changing its contents.

$ touch notes.txt

$ ls -l notes.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 sarah sarah 0 Feb 18 14:22 notes.txttouch is commonly used in scripts to create placeholder files, create multiple files at once, or update timestamps to signal that a file has been “touched” for automation purposes.

$ touch file1.txt file2.txt file3.txt

$ ls

file1.txt file2.txt file3.txtcp — Copy Files and Directories

cp copies a file from one location to another. The original file remains unchanged; a new copy is created at the destination.

$ cp notes.txt notes_backup.txt

$ ls

notes.txt notes_backup.txtCopy a file to a different directory:

$ cp notes.txt Documents/Copy a file to a different directory with a new name:

$ cp notes.txt Documents/project_notes.txtcp -r — copy a directory and all its contents recursively (required for directories):

$ cp -r projects/ projects_backup/cp -v — verbose mode, showing each file as it is copied (useful for tracking progress with many files):

$ cp -rv projects/ projects_backup/

'projects/' -> 'projects_backup/'

'projects/readme.txt' -> 'projects_backup/readme.txt'cp -p — preserve file attributes (permissions, timestamps, ownership) in the copy:

$ cp -p original.conf backup.confmv — Move or Rename Files and Directories

mv moves a file or directory to a new location. Unlike cp, the original is removed — it is relocated rather than duplicated. When used within the same directory, mv effectively renames the file.

Rename a file:

$ mv notes.txt project_notes.txt

$ ls

project_notes.txtMove a file to a different directory:

$ mv project_notes.txt Documents/Move and rename simultaneously:

$ mv old_name.txt Documents/new_name.txtMove a directory:

$ mv old_folder/ new_location/old_folder/Unlike cp, mv does not need the -r flag for directories — it moves them as a whole unit naturally.

rm — Remove Files and Directories

⚠️ Warning: rm permanently deletes files. There is no Trash or Recycle Bin when using rm in the terminal — deleted files are gone immediately and permanently. Use this command carefully, especially with the -r and -f flags.

Delete a single file:

$ rm old_file.txtrm -i — interactive mode, which asks for confirmation before deleting each file (recommended for beginners):

$ rm -i important.txt

rm: remove regular file 'important.txt'? yrm -r — remove a directory and all its contents recursively (required to delete directories):

$ rm -r old_projects/rm -f — force deletion without asking for confirmation, even for write-protected files. Use with extreme care.

rm -rf — the combination of recursive and force, which deletes a directory and everything inside it without any confirmation. This is the most dangerous rm combination — double-check your target before running it.

Safe alternatives to rm:

- Use

mv filename ~/.lo.cal/.share/Trash/to “delete” by moving to the Trash folder, allowing recovery. - Use the

trash-clipackage (sudo apt install trash-cli) to add atrashcommand that sends files to the graphical Trash with proper integration.

rmdir — Remove Empty Directories

rmdir removes a directory, but only if it is completely empty. This safety requirement makes it safer than rm -r for directory deletion.

$ rmdir empty_folder/If the directory contains any files or subdirectories, rmdir refuses to delete it:

$ rmdir projects/

rmdir: failed to remove 'projects/': Directory not emptyCategory 3: Viewing File Contents

These commands let you read the contents of files without opening them in a text editor. They are invaluable for quickly checking configuration files, log files, and documents.

cat — Concatenate and Display Files

cat (short for concatenate) reads one or more files and prints their contents to the terminal. It is the simplest way to view a file’s contents.

$ cat notes.txt

This is the content of my notes file.

It has multiple lines.cat can display multiple files in sequence:

$ cat file1.txt file2.txt

[contents of file1]

[contents of file2]cat -n — display file contents with line numbers:

$ cat -n script.sh

1 #!/bin/.bash

2 echo "Hello, World!"

3 exit 0cat works well for short files. For long files (more than a screenful), use less instead.

Creating a small file with cat: You can also use cat to create files by redirecting its output:

$ cat > newfile.txt

Type your content here.

Press Ctrl+D when done.Press Ctrl+D on a new line to finish.

less — View Files Page by Page

less is the right tool for reading long files. Unlike cat, which dumps the entire file to the terminal at once, less displays one page at a time and lets you scroll.

$ less /var/.log/syslogNavigating within less:

- Arrow keys or

j/k— scroll down/up one line - Space bar or

f— scroll forward one page b— scroll backward one pageg— go to the beginning of the fileG— go to the end of the file/search_term— search forward for text (pressnfor next match,Nfor previous)?search_term— search backwardq— quit and return to the terminal

less is particularly useful for reading log files, configuration files, and command output piped through it:

$ ls -la /usr/.bin | lesshead — View the Beginning of a File

head shows the first few lines of a file. By default it shows the first 10 lines.

$ head /etc/.passwd

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/.bash

daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/.sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin

bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/.sbin/nologin

...head -n 20 — show the first 20 lines (replace 20 with any number):

$ head -n 20 /var/.log/sysloghead -n 1 — show only the first line (useful for checking file headers or the first record of a CSV):

$ head -n 1 data.csv

date,name,value,categorytail — View the End of a File

tail shows the last few lines of a file. By default it shows the last 10 lines.

$ tail /var/.log/syslogtail -n 50 — show the last 50 lines:

$ tail -n 50 /var/.log/auth.logtail -f — follow mode, the most powerful tail option. It continuously displays new lines as they are added to the file, making it perfect for watching log files in real time:

$ tail -f /var/.log/syslogAs new events are logged, they appear on screen immediately. Press Ctrl+C to stop following.

This is invaluable for watching what is happening on your system in real time — monitor an installation, watch for errors as they occur, or track application activity.

grep — Search for Text in Files

grep (Global Regular Expression Print) searches for text patterns within files and prints matching lines. It is one of the most powerful and frequently used Linux commands.

Search for a word in a file:

$ grep "error" /var/.log/syslog

Feb 18 09:22:01 laptop kernel: error: device not found

Feb 18 10:15:33 laptop app: error: connection refusedSearch case-insensitively with -i:

$ grep -i "error" /var/.log/syslogShow line numbers with -n:

$ grep -n "TODO" my_script.sh

15: # TODO: add error handling

42: # TODO: optimize this loopSearch recursively through a directory with -r:

$ grep -r "database_host" /etc/.myapp/

/etc/.myapp/config.conf:database_host=localhostShow lines that do NOT match with -v:

$ grep -v "debug" /var/.log/syslogCount matching lines with -c:

$ grep -c "error" /var/.log/syslog

47grep becomes even more powerful when combined with other commands through pipes:

$ cat /var/.log/syslog | grep "error" | tail -20This finds all error messages in the log and shows the 20 most recent ones.

Category 4: System Information Commands

These commands tell you about your system’s current state — disk usage, memory, running processes, system identity, and more. They are essential for monitoring and understanding your Linux system.

df — Disk Free Space

df shows how much disk space is used and available on all mounted filesystems.

$ df -h

File.system Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/.sda1 50G 18G 30G 38% /

tmpfs 3.9G 0 3.9G 0% /dev/.shm

/dev/.sda2 200G 45G 145G 23% /homeThe -h flag makes sizes human-readable (G for gigabytes, M for megabytes). Without it, sizes are shown in 1K blocks.

df -h /home — check disk usage for a specific filesystem:

$ df -h /home

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/.sda2 200G 45G 145G 23% /homeCheck this regularly to avoid running out of disk space, which can cause system instability.

du — Disk Usage of Files and Directories

While df shows overall filesystem usage, du (disk usage) shows how much space specific files and directories consume.

du -h — show size of current directory and all subdirectories:

$ du -h ~/Documents

4.0K /home/sarah/Documents/notes

128M /home/sarah/Documents/projects

132M /home/sarah/Documentsdu -sh — show just the total size of a directory (summary, human-readable):

$ du -sh ~/Down.loads

2.3G /home/sarah/Downloadsdu -sh * — show the size of each item in the current directory:

$ du -sh *

4.0K Desktop

132M Documents

2.3G DownloadsThis is invaluable for finding which directories are consuming the most disk space when you are running low.

free — Memory Usage

free shows how much RAM and swap space is being used and how much is available.

$ free -h

total used free shared buff/cache available

Mem: 15Gi 4.2Gi 5.1Gi 512Mi 6.1Gi 10Gi

Swap: 2.0Gi 0B 2.0GiThe -h flag makes values human-readable. The most important column for available memory is available rather than free — available includes memory currently used for caching that can be immediately reclaimed if applications need it.

uname — System and Kernel Information

uname displays information about the operating system and kernel.

uname -r — show the kernel version currently running:

$ uname -r

6.8.0-35-genericuname -a — show all available system information (kernel name, hostname, kernel version, machine hardware):

$ uname -a

Linux laptop 6.8.0-35-generic #35-Ubuntu SMP PREEMPT_DYNAMIC Mon Apr 29 14:15:58 UTC 2024 x86_64 x86_64 x86_64 GNU/LinuxThis is useful when reporting bugs, checking compatibility, or verifying that a kernel update was applied successfully.

whoami — Current User Identity

whoami prints the username of the currently logged-in user. Simple but surprisingly useful in scripting and when working with multiple user accounts or sudo.

$ whoami

sarahid — User and Group Identity

id provides more detailed identity information, including your user ID number, primary group, and all group memberships.

$ id

uid=1000(sarah) gid=1000(sarah) groups=1000(sarah),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip)Seeing sudo in the groups list confirms that your account has administrator privileges.

uptime — System Running Time

uptime shows how long the system has been running, how many users are logged in, and the system load averages.

$ uptime

14:33:42 up 3 days, 6:22, 1 user, load average: 0.52, 0.41, 0.38The load averages show system load over the last 1, 5, and 15 minutes. Values below the number of CPU cores indicate a system with capacity to spare.

lsblk — List Block Devices

lsblk lists all storage devices (hard drives, SSDs, USB drives) and their partitions.

$ lsblk

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINT

sda 8:0 0 238.5G 0 disk

├─sda1 8:1 0 50G 0 part /

├─sda2 8:2 0 200G 0 part /home

└─sda3 8:3 0 2.0G 0 part [SWAP]

sdb 8:16 1 29.7G 0 disk

└─sdb1 8:17 1 29.7G 0 part /media/.sarah/USBThis command is useful for identifying drives before mounting, checking partition layouts, and understanding your storage configuration.

Category 5: Getting Help

Knowing how to get help from within the terminal itself is one of the most important meta-skills you can develop.

man — Manual Pages

man is the built-in documentation system for Linux commands. Every standard command has a manual page accessible through man.

$ man lsThis opens the full manual for the ls command, showing all its options, their descriptions, and usage examples. Navigate with arrow keys, search with /, and press q to quit.

Searching for a command by keyword: If you know what you want to do but not which command does it, man -k searches manual page descriptions:

$ man -k "disk usage"

df (1) - report file system disk space usage

du (1) - estimate file space usage–help — Quick Option Summary

Most commands support the --help flag (or sometimes -h), which displays a compact summary of the command’s options — much shorter and more immediately useful than the full man page.

$ ls --help

Usage: ls [OPTION]... [FILE]...

List information about the FILEs (the current directory by default).

...--help is ideal when you remember a command but forget a specific option. It is faster than opening the full man page when you just need a quick reminder.

type — Find Out What a Command Is

type tells you what kind of thing a command name refers to — whether it is an external program, a shell built-in, an alias, or a function.

$ type ls

ls is aliased to 'ls --color=auto'

$ type cd

cd is a shell builtin

$ type python3

python3 is /usr/.bin/python3This is useful when a command behaves unexpectedly and you want to understand whether it is calling a custom alias or the actual system program.

which — Locate a Command

which shows the full path of the executable that would be run when you type a command name.

$ which python3

/usr/.bin/python3

$ which bash

/bin/.bashUseful for confirming which version of a program is being used when multiple versions are installed.

Category 6: Working with Command Output

These commands help you manage and process the output of other commands.

echo — Display Text

echo prints text to the terminal. While simple, it is extremely useful in scripts for displaying messages, and it works as a quick test of variable values.

$ echo "Hello, World!"

Hello, World!

$ echo $HOME

/home/sarah

$ echo "Today is $(date)"

Today is Wed Feb 18 14:33:22 UTC 2026The $(command) syntax (command substitution) runs the command inside the parentheses and inserts its output into the echo string.

wc — Word, Line, and Character Count

wc (word count) counts lines, words, and characters in files or piped input.

wc -l — count lines:

$ wc -l /etc/.passwd

45 /etc/.passwdwc -w — count words:

$ wc -w document.txt

1247 document.txtwc -c — count characters (bytes):

$ wc -c image.jpg

2847392 image.jpgCombined with pipes, wc -l is especially useful for counting results:

$ ls /usr/.bin | wc -l

1284sort — Sort Lines

sort arranges lines of text in alphabetical or numerical order.

$ sort names.txt

Alice

Bob

Carol

Davidsort -r — reverse order (Z to A or descending numbers):

$ sort -r names.txtsort -n — numerical sort (so 10 comes after 9, not before 2):

$ sort -n numbers.txtsort -u — sort and remove duplicate lines:

$ sort -u file.txthistory — Command History

history displays a numbered list of previously executed commands in your current shell session (and from previous sessions saved in ~/.ba.sh_history).

$ history

498 cd /etc

499 cat hosts

500 cd ~

501 ls -la

502 historyRerun a command by number: Type ! followed by the command number:

$ !499

cat hostsRerun the last command: !! repeats the most recent command:

$ !!

historySearch history: Press Ctrl+R in the terminal to enter reverse history search. Start typing any part of a previous command and the most recent matching command appears. Press Ctrl+R again to cycle through older matches. Press Enter to execute the found command.

Clear history: history -c clears the current session’s history (useful for security when you have typed sensitive information like passwords).

Combining Commands: Quick Examples

The real power of the terminal emerges when you combine these basic commands. Here are a few practical combinations using only the commands covered in this article:

Find the 10 largest items in your Downloads folder:

$ du -sh ~/Down.loads/* | sort -rh | head -10Count how many error messages appeared in today’s system log:

$ grep "$(date '+%b %e')" /var/.log/syslog | grep -i "error" | wc -lFind all .txt files in your Documents folder:

$ ls ~/Docu.ments/*.txtSee the last 20 lines of the system log, updated in real time:

$ tail -f /var/.log/syslog | grep -i "error"Create a backup of a configuration file before editing it:

$ cp /etc/.hosts /etc/.hosts.backupEssential Command Reference Table

| Command | Purpose | Most Useful Option | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

pwd | Show current directory | — | pwd |

ls | List directory contents | -la (all, long format) | ls -la |

cd | Change directory | .. (go up), ~ (go home) | cd ~/Docu.ments |

mkdir | Create directory | -p (create parents) | mkdir -p a/b/c |

touch | Create empty file | — | touch notes.txt |

cp | Copy file/directory | -r (recursive) | cp -r dir/ backup/ |

mv | Move or rename | — | mv old.txt new.txt |

rm | Delete file/directory | -i (confirm each) | rm -i file.txt |

cat | Display file contents | -n (line numbers) | cat -n script.sh |

less | Page through file | — | less /var/.log/syslog |

head | Show first N lines | -n (number) | head -n 20 file.txt |

tail | Show last N lines | -f (follow) | tail -f /var/.log/syslog |

grep | Search text in files | -i (case insensitive) | grep -i "error" log.txt |

df | Disk space usage | -h (human readable) | df -h |

du | Directory/file sizes | -sh (summary) | du -sh ~/Down.loads |

free | Memory usage | -h (human readable) | free -h |

uname | System information | -a (all info) | uname -a |

whoami | Current username | — | whoami |

uptime | System uptime/load | — | uptime |

man | Command manual | -k (keyword search) | man ls |

echo | Print text | — | echo $HOME |

wc | Count lines/words | -l (lines only) | wc -l file.txt |

sort | Sort lines | -n (numeric) | sort -n numbers.txt |

history | Command history | — | history |

Tips for Building Command Habits

Knowing commands intellectually is different from having them as muscle memory. A few practices will help you build genuine fluency faster.

Use Tab completion for everything. The moment you start typing a command or filename, press Tab. If there is only one possibility, it completes immediately. If there are multiple possibilities, Tab twice shows them all. Using Tab constantly prevents typos and speeds up everything you do in the terminal.

Use the Up arrow to recall recent commands. Rather than retyping a long command you ran a few minutes ago, press Up to scroll through your command history. This is especially useful for long commands with many options that would be tedious to retype.

Make mistakes on purpose in a safe environment. Create a temporary directory (mkdir ~/practice) and experiment freely there. Create files, delete them, move them around, search through them. Learning through hands-on experimentation is faster and more durable than reading alone.

Read error messages carefully. When a command fails, the terminal prints an error message explaining what went wrong. These messages are not just noise — they are specific, informative, and usually tell you exactly what the problem is. New users often gloss over error messages; experienced users read them carefully because they usually contain the solution.

Run one command at a time when learning. Avoid copying and pasting multi-command sequences from tutorials until you understand what each command does. Run commands individually so you can see each command’s output and understand what happened before proceeding to the next step.

What You Can Do Right Now

With the commands in this article, you are already capable of accomplishing a meaningful range of real tasks:

You can navigate your entire file system, exploring any directory you choose. You can create organized folder structures for your projects. You can copy important files before modifying them. You can read configuration files and log files without opening a graphical editor. You can monitor disk space and memory to keep your system healthy. You can search through files for specific text. You can review your command history to recall what you did earlier. You can look up the documentation for any command you encounter.

This foundation is genuinely useful. Many everyday Linux administration tasks require only these basic commands — checking why an application failed (looking at log files with tail -f and grep), managing disk space (checking with df and du), organizing files (using cp, mv, mkdir), and understanding your system (using uname, free, uptime).

Conclusion: A Foundation That Builds on Itself

The commands in this article are not just a beginner’s list to be discarded as your skills grow. They are the permanent foundation of all terminal work. Professional system administrators with decades of experience use ls, cat, grep, and cd constantly — not because they have not learned anything more advanced, but because these commands are genuinely the right tool for the tasks they perform most often.

As you continue through this Linux series, every more advanced topic — managing permissions, writing shell scripts, installing software, configuring services — builds directly on these basics. Each new command you learn extends and refines the vocabulary you have built here.

The next article in this series covers installing software in Linux using package managers — one of Linux’s greatest strengths and a topic that immediately becomes practical from your first day of Linux use.