Introduction

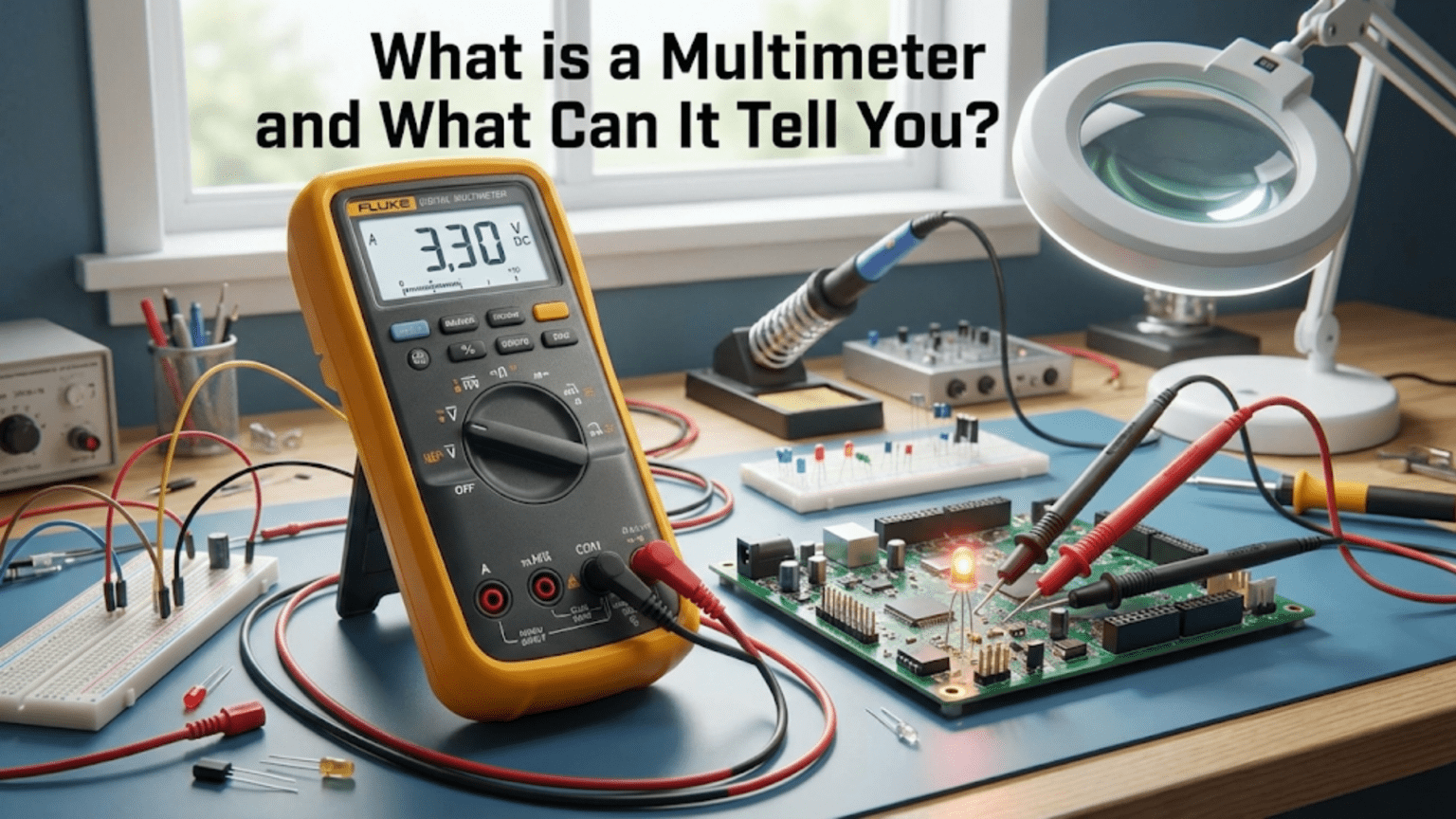

A multimeter is the single most essential measurement tool in electronics, functioning as the eyes and diagnostic instrument that reveal the invisible electrical quantities flowing through circuits, transforming abstract concepts of voltage, current, and resistance into concrete numerical readings that confirm whether circuits operate correctly or help identify problems when they malfunction. Without a multimeter, electronics work becomes largely guesswork because you cannot verify that power supplies deliver expected voltages, confirm that resistors have correct values, check whether connections conduct electricity, or measure the current flowing through components. The multimeter transforms invisible electrical phenomena into visible measurements, enabling the transition from reading about electronics to actually understanding what happens inside working circuits through direct observation and verification.

For beginners encountering multimeters for the first time, these devices might appear intimidating with their multiple dial positions, various input jacks, and displays showing numbers whose meaning may not be immediately clear. Yet multimeters are fundamentally straightforward instruments once you understand their basic organization and purpose. The dial or buttons select what quantity you want to measure—voltage, current, resistance, or other functions. The display shows the measured value in appropriate units. The input jacks accept the test probes that connect to the circuit being measured. This simple input-process-output organization underlies all multimeter operation, with the complexity arising mainly from the variety of quantities that can be measured and the different ranges needed to accommodate values spanning many orders of magnitude from millivolts to hundreds of volts, from microamps to tens of amperes, and from ohms to megohms.

The name “multimeter” reflects the instrument’s ability to measure multiple electrical quantities in one device, replacing what previously required separate voltmeters, ammeters, and ohmmeters with a single versatile instrument that performs all three measurements plus additional functions. Modern digital multimeters, often abbreviated DMM, display measurement results as numerical values on digital screens, contrasting with older analog multimeters that used moving needle indicators on printed scales. Digital meters have largely replaced analog types for most applications because they are easier to read, more accurate, more rugged, and less expensive to manufacture, though analog meters still offer advantages for observing rapidly changing values where the moving needle provides visual indication of variation that numerical displays cannot easily convey.

The practical value of multimeters extends far beyond electronics hobbyists to encompass professional electricians testing household wiring, automotive technicians diagnosing vehicle electrical systems, HVAC technicians troubleshooting heating and cooling equipment, and anyone working with electrical or electronic systems who needs to measure electrical quantities to verify proper operation or diagnose faults. This universal applicability makes multimeter skills valuable life skills extending beyond electronics hobbies into practical home maintenance, automotive work, and countless other domains where electrical measurements provide essential information for troubleshooting and repair.

This comprehensive guide will build your understanding of multimeters from basic concepts through practical usage, examining what multimeters measure and why these measurements matter, how multimeters are organized with their dials, displays, and input jacks, the different measurement functions and when to use each, how to read and interpret measurements correctly, common measurement mistakes and how to avoid them, and the progression from basic measurements to more advanced multimeter capabilities as your skills develop. By the end, you will understand multimeters thoroughly enough to confidently measure voltage, current, and resistance in circuits, interpret readings correctly, and use measurement results to verify circuit operation and troubleshoot problems.

What Multimeters Measure: The Three Fundamental Quantities

Understanding what multimeters measure and why these measurements matter provides the foundation for using them effectively in electronics work.

Voltage: Electrical Pressure

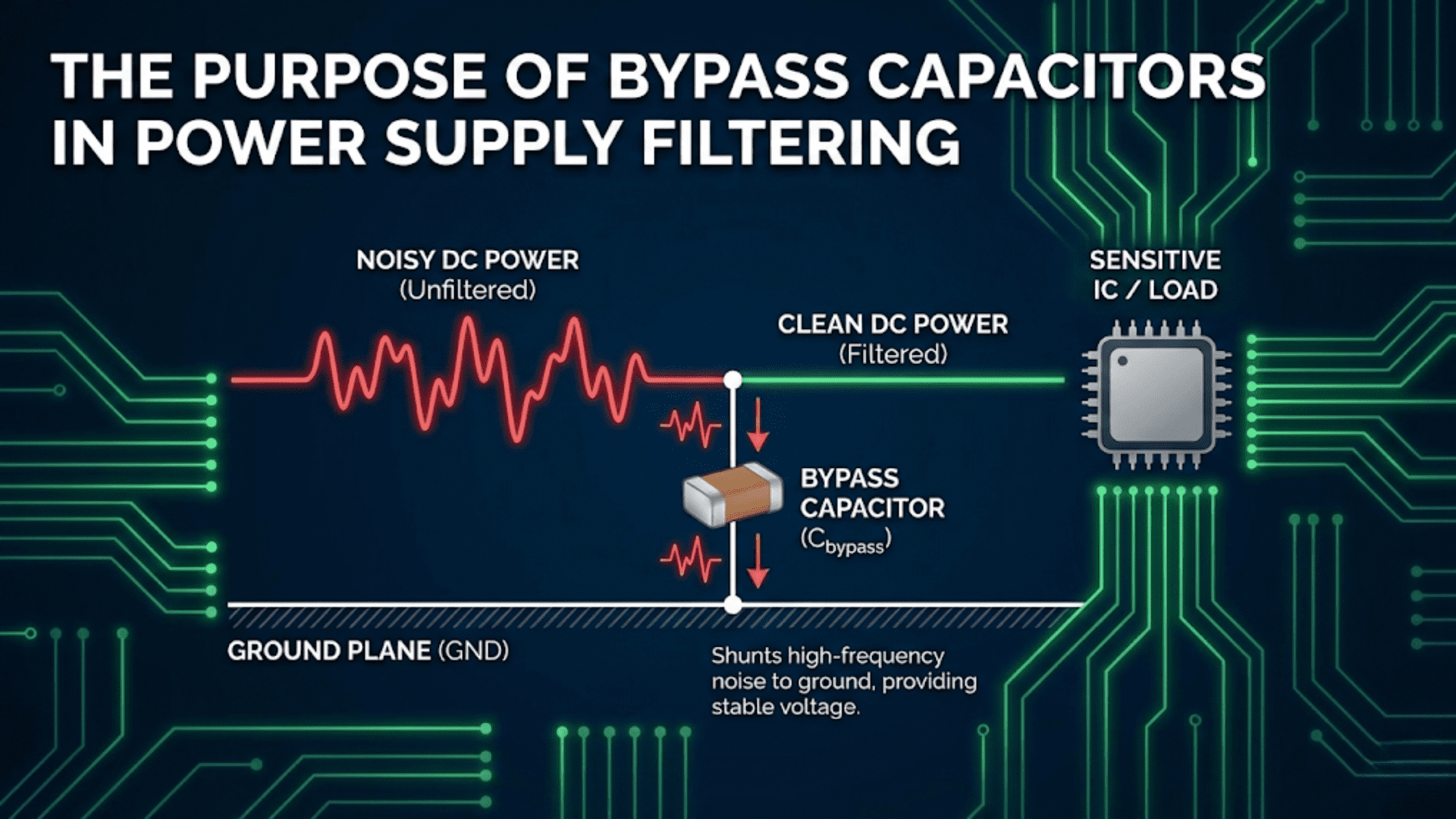

Voltage represents electrical pressure or potential difference between two points, analogous to water pressure in plumbing systems where higher pressure pushes water through pipes with greater force. In electrical terms, voltage measures the energy difference per unit charge between two circuit points, determining how strongly current flows through resistance connecting those points. The multimeter measures voltage by connecting its high-impedance voltage measurement circuit between the two points of interest, drawing negligible current while sensing the voltage difference.

Voltage measurements answer fundamental questions in electronics work. Does this battery still have adequate charge, or has voltage dropped indicating depletion? Does this power supply deliver the specified voltage under load? What voltage appears at this circuit node relative to ground? Is this voltage regulator functioning properly? These questions and countless others are answered through voltage measurement, making it perhaps the most frequently used multimeter function. Voltage is measured in volts, with typical electronics work involving voltages from millivolts for small signals through common power supply voltages of three point three, five, nine, or twelve volts, to line voltages of one hundred twenty or two hundred forty volts in household electrical systems.

Multimeters typically provide separate measurement ranges for DC voltage—steady voltage that does not change polarity—and AC voltage that alternates polarity at specific frequencies like the sixty hertz household power in North America or fifty hertz in many other regions. DC voltage measurement is essential for battery-powered circuits, DC power supplies, and most electronics work. AC voltage measurement applies to household power, transformers, and AC signal sources. The distinction matters because measurement circuits handle DC and AC differently, with AC measurements typically showing RMS or root-mean-square values representing the effective voltage of the alternating waveform.

Current: Electrical Flow Rate

Current measures the rate of electrical charge flow through a circuit, analogous to water flow rate in gallons per minute or liters per second. Higher current means more charge flows per unit time, delivering more energy and potentially creating more heating in resistive elements. Current is measured in amperes or amps, with typical electronics work involving currents from microamps or milliamps for small signal circuits through hundreds of milliamps for LEDs and small motors to multiple amperes for high-power devices.

Current measurement requires inserting the multimeter in series with the current path, meaning the circuit must be broken and the meter inserted so all current flows through the meter’s current-sensing circuit. This series insertion requirement distinguishes current measurement from voltage and resistance which measure across components in parallel. The multimeter’s current measurement circuit presents very low resistance—often less than one ohm—so inserting it in series does not significantly affect current flow, though this low resistance also means accidentally connecting the meter in parallel when set to current mode creates a short circuit that may blow the meter’s protective fuse.

Current measurements answer different questions than voltage measurements. How much current does this circuit draw from the power supply? Does this LED’s current-limiting resistor actually limit current to the intended value? Does this motor draw normal current, or does excessive current indicate bearing problems or overload? Is this circuit consuming more power than expected? These practical questions require current measurement, making it an essential capability despite being less frequently used than voltage measurement in typical electronics troubleshooting.

Resistance: Opposition to Current Flow

Resistance quantifies how strongly materials oppose current flow, measured in ohms with the Greek letter omega as the symbol. Conductors like copper wire have very low resistance—milliohms per foot—allowing substantial current flow with minimal voltage drop. Insulators have extremely high resistance—megohms or higher—preventing significant current flow even at high voltages. Resistors provide controlled amounts of resistance for current limiting, voltage division, and other circuit functions, with values spanning ohms through megohms.

Resistance measurement applies test current to the component being measured and measures resulting voltage, calculating resistance using Ohm’s Law. This measurement must occur with no other voltage sources present because external voltages would affect measurement accuracy or potentially damage the meter. Therefore, resistance measurements always require powering off circuits and often require removing one lead of the component being measured to isolate it from other circuit elements that would parallel its resistance and affect readings.

Resistance measurements verify that resistors have expected values matching color code markings, that wires and connections have low resistance indicating good conductivity, that insulation has high resistance preventing current leakage, and that components suspected of failure have reasonable resistance rather than opens or shorts indicating damage. Resistance measurement also enables crude testing of component functionality—measuring transistor junction resistances or checking whether diodes show high resistance in reverse and low resistance in forward bias—though these tests are fairly coarse compared to dedicated component testing functions.

Additional Measurement Functions

Beyond the three basic measurements, many multimeters provide additional functions increasing their versatility. Continuity testing applies small test current and beeps if resistance is very low—typically below a few dozen ohms—enabling quick verification that wires are connected without watching resistance values. This audible feedback dramatically speeds checking multiple connections because you listen for the beep rather than reading the display.

Diode testing applies forward bias voltage and measures the voltage drop across the diode junction, typically around zero point six to zero point seven volts for silicon diodes or one point eight to three volts for LEDs depending on color. This measurement confirms diodes function correctly and have expected forward voltage drop, while also revealing shorts where voltage drop is near zero or opens where no current flows. Capacitance measurement found on some meters determines capacitor values, particularly useful for unmarked capacitors or verifying that capacitors match nominal ratings.

Frequency measurement determines how many cycles per second occur in AC signals, useful for checking oscillator frequencies or diagnosing AC power problems. Temperature measurement with thermocouple probes enables monitoring circuit temperatures to verify adequate cooling or identify overheating components. These additional functions vary widely across multimeter models, with basic meters offering perhaps voltage, current, resistance, and continuity while advanced meters add many specialized measurements supporting professional troubleshooting applications.

Multimeter Anatomy: Controls and Connections

Understanding the physical organization of multimeters and how to operate their controls enables correct measurement setup and prevents damage from improper connections.

The Selector Dial or Buttons

The most prominent control on most multimeters is a rotary selector dial with positions for different measurement functions and ranges, or on some digital meters, buttons that select functions electronically. Each dial position selects a specific measurement type—DC voltage, AC voltage, DC current, AC current, resistance, or other functions—and often also selects a measurement range indicating the maximum value the meter can display in that position. For example, a twenty-volt DC voltage position measures DC voltages from zero to twenty volts, while a two-hundred-volt position measures up to two hundred volts.

Manual ranging meters require selecting appropriate ranges before measuring, starting with the highest range if the expected value is unknown to avoid overloading the meter, then switching to lower ranges that provide better resolution once you determine the approximate value. Auto-ranging meters automatically select appropriate ranges eliminating manual range selection, making them easier to use particularly for beginners unfamiliar with estimating voltages before measurement. The trade-off is slightly higher cost and sometimes slower measurement updates as the meter determines the best range.

The selector dial must be set correctly for the intended measurement type because selecting current mode when measuring voltage, or vice versa, can damage the meter or the circuit. Always verify the dial position matches your intended measurement before connecting test probes to circuits. Some meters include position labels with symbols indicating measurement types—a V with straight and dashed lines for DC voltage, a V with sine wave symbol for AC voltage, an A for current, and the omega symbol for resistance—so learning these symbols helps operate different multimeter models that might arrange dial positions differently.

Input Jacks and Test Probe Connections

Multimeters typically have three or four input jacks accepting test probe connections. The common jack, usually labeled COM and often colored black, accepts the black or negative test probe and serves as the reference point for all measurements. This jack connects to circuit ground or the negative test point for voltage measurements, and forms one end of the current path for current measurements.

The voltage and resistance jack, often labeled with a V-omega symbol and colored red, accepts the red or positive test probe for voltage and resistance measurements. When measuring voltage, this probe touches the positive or higher-potential circuit point, with the voltage displayed being the difference between this probe and the common probe. For resistance measurements, the polarity does not matter since resistance is symmetric, though by convention the red probe typically touches one component lead while the black probe touches the other.

Current measurement requires moving the red test probe to a separate current jack because current measurement circuits differ substantially from voltage measurement circuits. Meters often provide two current jacks—one for small currents perhaps up to two hundred milliamps or four hundred milliamps, and another for larger currents up to ten or twenty amperes. The small current jack typically has a replaceable fuse protecting the meter from overcurrent, while the large current jack may be unfused or have a very high-rated fuse. Always estimate expected current and use the appropriate jack to avoid blowing fuses or damaging the meter.

The critical importance of connecting probes to correct jacks cannot be overstated because measuring voltage with probes connected to the current jacks creates a short circuit through the meter’s low-resistance current shunt, potentially damaging circuits or blowing protective fuses. Similarly, attempting current measurement with probes in the voltage jacks prevents current flow and yields no reading. Developing habits of always verifying probe jack connections match the selected measurement function prevents these common errors.

The Display and Its Indicators

Digital multimeters use numeric displays showing measurement values along with indicators for units, decimal point position, and various status symbols. Seven-segment LCD displays are most common, showing numbers typically with three and a half or four and a half digits of resolution. Three and a half digits means the display can show up to 1999—the most significant digit can be only one or blank—while four and a half digits displays up to 19999, providing finer resolution.

Decimal point position shifts automatically based on the measured value or selected range, with the meter displaying results in the most readable form. A voltage measurement of zero point zero five volts might display as “50 mV” on the meter with the decimal point positioned and the “mV” indicator lit to show millivolts, making the value easier to read than “0.050 V” would be. Understanding these automatic scaling and decimal point adjustments prevents misreading values by orders of magnitude.

Status indicators include low battery warnings signaling when the internal battery needs replacement, overvoltage or overload indicators warning that the measured value exceeds the selected range, continuity or diode test symbols showing which mode is active, and hold indicators if the meter has a hold function freezing the display at the current reading. Reading these indicators prevents incorrect interpretation of measurements and alerts you to conditions requiring attention like battery replacement or range selection adjustment.

Making Basic Measurements Correctly

Practical measurement techniques ensure accurate results while preventing damage to meters, circuits, or components being measured.

Measuring Voltage Safely and Accurately

Voltage measurement begins by setting the multimeter selector to the appropriate voltage function—DC voltage for batteries and DC power supplies, AC voltage for household power or AC signal sources. If the expected voltage is unknown, start with the highest voltage range and work downward to find a range providing adequate resolution without overloading. Connect the black probe to circuit ground or the negative measurement point and the red probe to the positive measurement point or the circuit node whose voltage you want to measure relative to ground.

The meter displays the voltage difference between the probes, showing positive values when the red probe is at higher potential than the black probe, and negative values when polarity is reversed. For DC voltage measurements, polarity matters because the sign indicates whether the red probe is more positive or more negative than the black probe. For AC voltage measurements, polarity is meaningless since AC voltages alternate polarity, and the meter displays the RMS magnitude regardless of probe orientation.

Common voltage measurement applications include checking battery voltage to verify charge state, measuring power supply outputs to confirm proper regulation, probing circuit nodes to trace signals and verify expected voltage levels, and checking voltage drops across components to verify correct operation. Always measure with circuit power on since voltage only exists when energy sources are active, and maintain probe contact firmly during measurement ensuring good electrical connection that does not create intermittent readings.

Measuring Current Without Damage

Current measurement requires significantly more care than voltage measurement because the meter must be inserted in series with the current path, requiring breaking the circuit by disconnecting a component lead or cutting a wire, and because accidentally measuring current across a voltage source creates a short circuit. Before measuring current, estimate the expected current and verify the meter can handle it without exceeding its maximum rated current for the selected range.

With the circuit power off, break the circuit at a point where you want to measure current—typically by removing a component lead from the breadboard or disconnecting a wire. Set the multimeter to the appropriate current function and range, moving the red probe to the correct current jack based on whether expected current falls in the small current range or large current range. Connect the black probe to one side of the break and the red probe to the other side, effectively inserting the meter in series so current flows through the meter’s internal current sensing circuit.

Power on the circuit and read the current from the meter display. The very low resistance of the meter’s current measurement circuit means it does not significantly affect circuit operation beyond what would occur if the circuit were simply reconnected without the meter present. However, if measured current exceeds the meter’s maximum rating for the selected range, the protective fuse may blow or the meter may be damaged, so always ensure your current estimate and selected range are appropriate before powering the circuit.

After completing current measurement, power off the circuit before removing the meter and reconnecting the circuit to its normal configuration. Leaving the circuit broken with the meter inserted prevents normal operation, and removing the meter without reconnecting the circuit leaves an open circuit that will not function. Current measurement is inherently more disruptive than voltage or resistance measurement because it requires breaking and reconnecting circuits, motivating careful planning of measurement points to minimize circuit disruption.

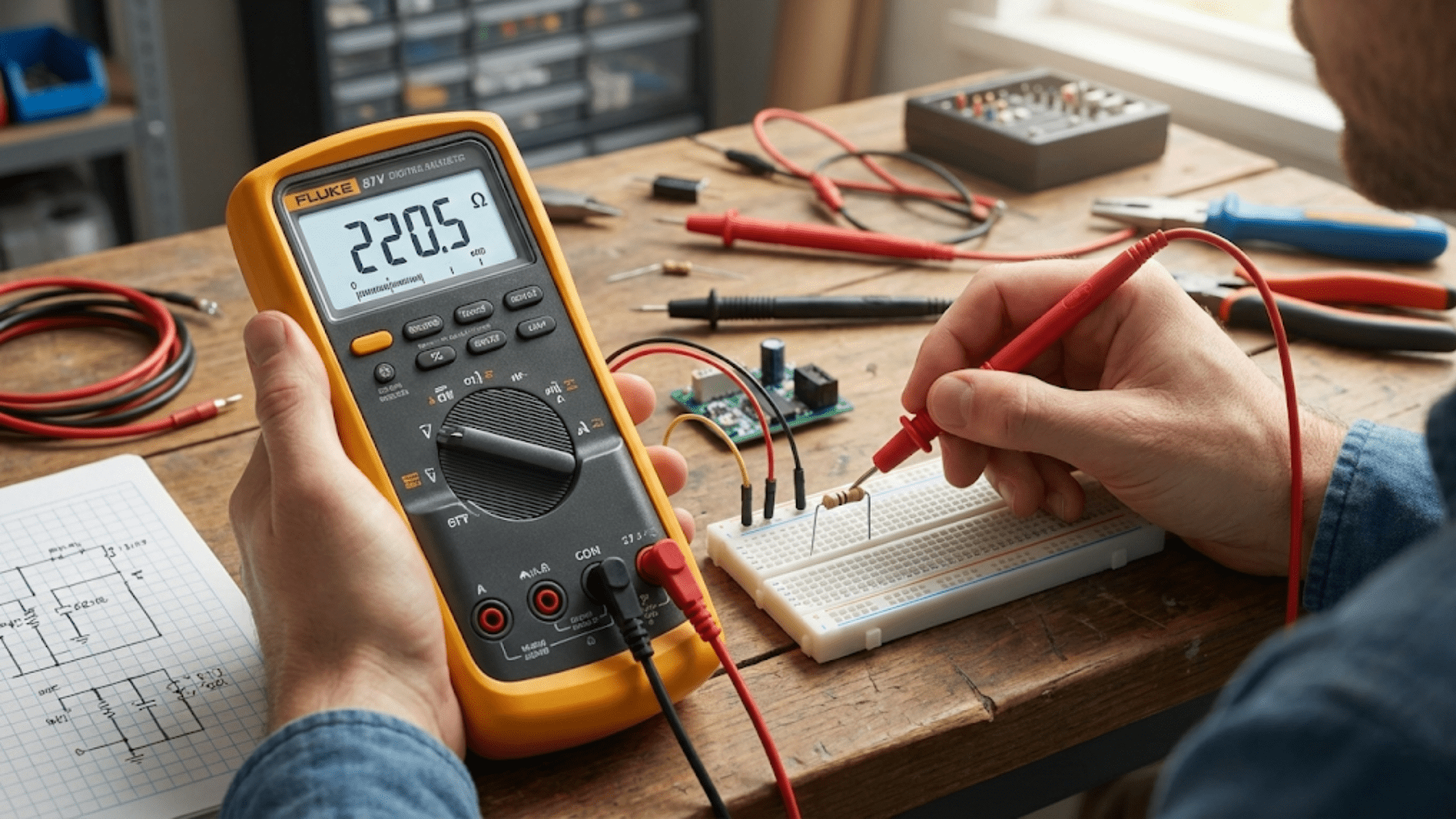

Measuring Resistance and Testing Continuity

Resistance measurement and continuity testing require circuits to be powered off and, ideally, the component being measured to be isolated from other circuit elements. The meter applies a small test current—typically a milliamp or less—and measures the resulting voltage to calculate resistance. Any external voltages from batteries or power supplies will interfere with this measurement, potentially giving erroneous readings or damaging the meter. Always disconnect power before resistance measurements.

For components in circuits, resistance measurements often show combined resistance of parallel paths through the component you want to measure and other circuit elements connected to it. Removing one component lead isolates it from parallel paths, ensuring the measured resistance represents only that component rather than the parallel combination. This isolation is particularly important when measuring resistors in circuits containing other resistors, capacitors, or semiconductor devices that might provide parallel conduction paths.

Continuity testing works similarly to resistance measurement but provides audible feedback—a beep or tone—when resistance is below a threshold typically around one hundred ohms or less. This enables quickly checking whether wires are connected, switches are closed, or circuit board traces are continuous without needing to watch the display. Continuity testing is invaluable for verifying breadboard connections, checking cables and wires for breaks, and confirming solder joints conduct properly.

Common Measurement Mistakes and Safety Considerations

Understanding typical errors prevents damage to meters and circuits while ensuring measurement accuracy and personal safety.

Incorrect Function or Range Selection

Setting the meter to measure current when you intend to measure voltage, or vice versa, ranks among the most common and potentially damaging multimeter mistakes. Measuring voltage with the meter set to current mode creates a short circuit through the meter’s low-resistance current shunt, potentially blowing the protective fuse or damaging the meter if current exceeds fuse rating. Measuring current with the meter set to voltage mode prevents current flow and yields no reading because the meter’s high input impedance when measuring voltage blocks current.

The remedy is always verifying that the selector dial matches your intended measurement before connecting probes to the circuit. Make it a habit to consciously check the dial position and think “I am measuring voltage, so the dial should be on DC volts or AC volts” before touching probes to circuits. This conscious verification prevents automatic or distracted probe placement while the meter is set incorrectly.

Selecting too low a range causes meter overload indicated by display blanking, showing an overload symbol, or displaying the maximum value the range can show. While generally not damaging to the meter, overload prevents obtaining actual measurements and requires switching to a higher range. Conversely, selecting too high a range reduces resolution and may show zero or very small values when the actual measurement is within the meter’s capability but below the selected range’s sensitivity.

Probe Connection Errors

Connecting test probes to wrong input jacks creates the same problems as incorrect function selection because the jacks determine whether the meter measures with high impedance for voltage or low impedance for current. Always verify the red probe connects to the voltage jack for voltage measurements and moves to the appropriate current jack for current measurements. Many meters have the voltage and resistance jack combined since both use similar high-impedance input circuits, but current jacks are always separate requiring deliberate probe relocation when switching between voltage and current measurement.

Poor probe contact with circuit points causes intermittent readings or incorrect measurements as contact resistance affects readings or connection breaks entirely. Probe tips should press firmly against metal contacts, wire ends, or component leads ensuring reliable electrical connection. Oxidized probe tips develop insulating layers preventing good contact, requiring periodic cleaning with fine sandpaper or replacing probes when tips become too degraded to maintain good contact.

Safety Hazards in High Voltage Measurement

Measuring line voltage—one hundred twenty or two hundred forty volts AC in household electrical systems—presents shock hazards requiring careful probe handling and awareness of electrocution risks. The meter itself withstands these voltages safely if rated for CAT II or higher electrical safety categories, but human contact with exposed probe tips or circuit conductors at line voltage can deliver dangerous or fatal shocks.

When measuring line voltage, ensure only the insulated probe handles contact your hands with no contact with metal probe tips or shafts. Use one hand for probe placement while keeping the other hand away from circuits and grounded metal objects to prevent creating a current path through your body. Never assume circuits are de-energized—always verify with the multimeter that voltage is actually absent before working on circuits. Many electrical accidents occur when people assume circuits are off when they are actually still energized.

Low voltage DC circuits below fifty volts present minimal shock hazards under normal conditions, though short circuits can create fire or explosion hazards in high current systems like automotive batteries or large battery packs. Always use appropriate caution and awareness when working with electrical systems regardless of voltage levels.

Conclusion: The Multimeter as Your Electronics Companion

The multimeter transforms invisible electrical phenomena into visible, quantifiable measurements, enabling verification that circuits operate correctly and providing diagnostic information when they malfunction. Understanding what multimeters measure—voltage, current, and resistance as the three fundamental electrical quantities—and how these measurements reveal circuit behavior provides the foundation for effective multimeter use. The physical organization of multimeters with selector dials, input jacks, and displays follows logical patterns that become intuitive with practice, though careful attention to function selection and probe connections prevents common errors that damage meters or yield incorrect readings.

Voltage measurement as the most frequently used multimeter function enables checking power supply outputs, verifying battery charge states, probing circuit nodes to trace signals, and confirming expected voltage levels throughout circuits. Current measurement reveals how much electrical flow occurs through circuit paths, enabling verification that power consumption matches expectations and identification of excessive current indicating faults. Resistance measurement confirms component values, verifies continuity of connections, and provides crude component testing revealing opens or shorts.

Proper measurement technique ensures accuracy while preventing damage to meters and circuits. Voltage measurements require parallel connection with power on, current measurements require series insertion with appropriate range selection and jack connections, and resistance measurements require power off and often component isolation from circuits. Common mistakes including incorrect function selection and improper probe placement are easily avoided through conscious verification of meter settings before connecting probes to circuits.

The multimeter deserves its status as the single most essential electronics tool because measurement capability is fundamental to understanding circuit operation, verifying correct assembly, and diagnosing problems. Every electronics workspace needs a multimeter, and developing confidence in measurement techniques through regular practice accelerates learning by enabling immediate verification of theoretical predictions against actual circuit behavior. The modest investment in even an inexpensive multimeter pays enormous dividends in capability, understanding, and troubleshooting effectiveness throughout your electronics journey.