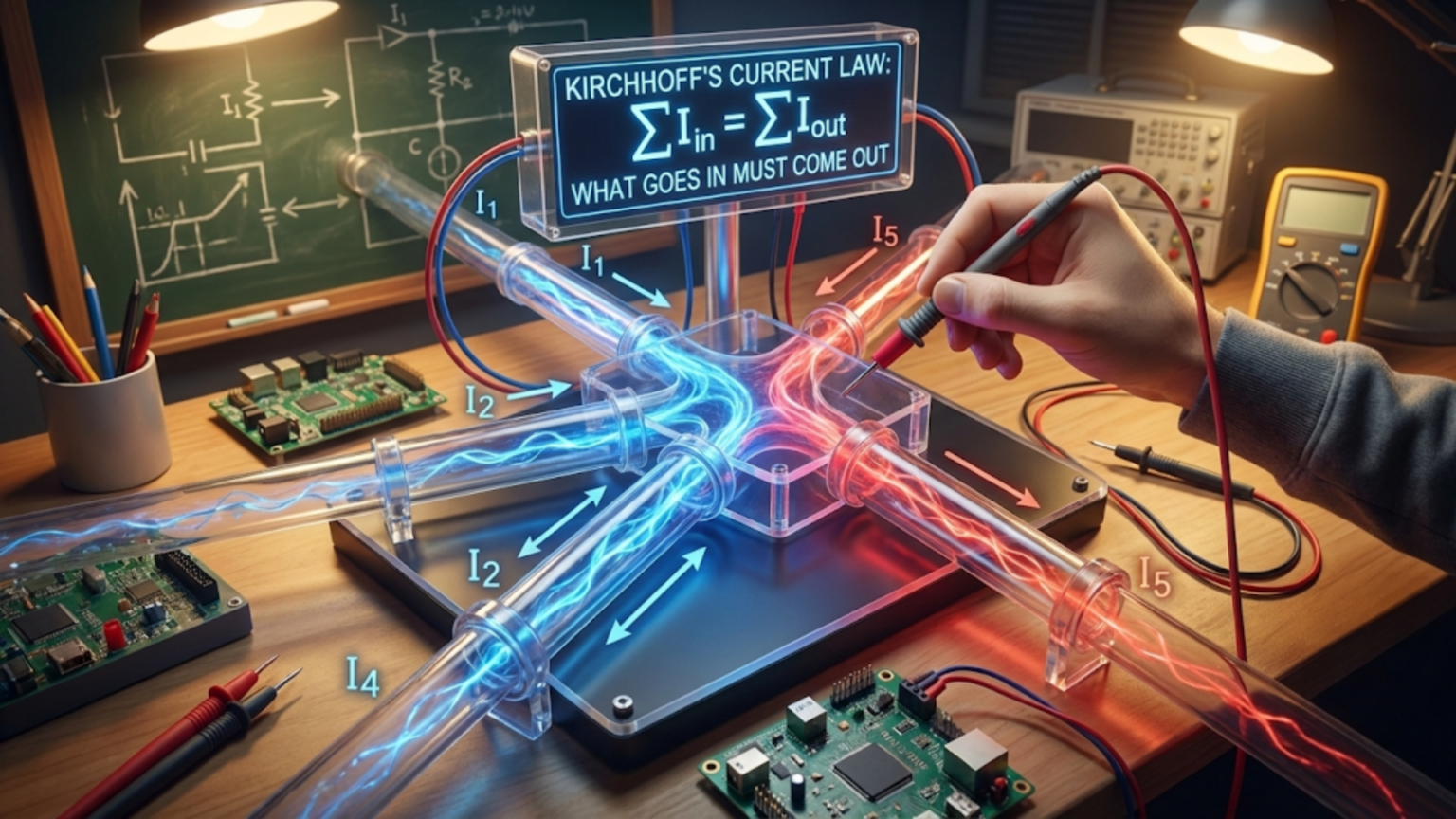

Kirchhoff’s Current Law (KCL) states that the algebraic sum of all currents entering and leaving any node (junction point) in an electrical circuit must equal zero, based on the principle of charge conservation. In simpler terms, the total current flowing into a node must equal the total current flowing out of that node, making it an essential tool for analyzing complex circuits with multiple branches and current paths.

Introduction: The Conservation of Electric Charge

Imagine standing at a busy intersection where multiple roads meet. Cars flow in from various directions and flow out along different paths. If you count carefully, you’ll notice something fundamental: the number of cars entering the intersection must equal the number leaving it (assuming no parking lot at the intersection). Cars don’t mysteriously appear or disappear—they just redistribute themselves along different paths.

This same principle applies to electric current at circuit junctions. Electric charge, like cars at an intersection, cannot be created or destroyed at a junction point. This fundamental truth forms the basis of Kirchhoff’s Current Law (KCL), one of the most important tools in circuit analysis.

Named after German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff, who formulated it in 1845, this law provides a systematic way to analyze circuits that would be impossibly complex using only Ohm’s Law. While Ohm’s Law tells us how voltage, current, and resistance relate in a single component, Kirchhoff’s Current Law helps us understand how current distributes itself when it encounters junctions where circuit paths split or merge.

Whether you’re designing a simple LED circuit with multiple branches, troubleshooting a malfunctioning power distribution system, or analyzing a complex integrated circuit, KCL provides the framework for understanding current flow. It’s not just a mathematical tool—it’s a reflection of a fundamental physical law: the conservation of electric charge.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore KCL from its theoretical foundations to practical applications. We’ll learn how to identify nodes, set up KCL equations, solve for unknown currents, and apply this principle to real-world circuit problems. By the end, you’ll understand not just what KCL states, but why it’s true and how to use it as a powerful analytical tool in your electronics work.

What is Kirchhoff’s Current Law?

The Basic Statement

Kirchhoff’s Current Law can be stated in several equivalent ways:

Formal statement: The algebraic sum of all currents entering and leaving a node equals zero.

Practical statement: The total current flowing into a node equals the total current flowing out of that node.

Mathematical statement: ΣI_in = ΣI_out, or equivalently, ΣI = 0 (when you assign consistent signs to currents)

The symbol Σ (sigma) means “sum of,” so ΣI_in means “the sum of all currents flowing into the node.”

What is a Node?

Before we can apply KCL, we need to understand what constitutes a node:

Definition: A node is any point in a circuit where two or more components connect together. It’s a junction where current can split or combine.

Simple node: The most common type is where exactly three or more wires meet at a single point. For example, where a wire from a battery splits to go to two different resistors.

Extended node: Sometimes an entire section of wire with no components between connection points is considered a single node. If three resistors all connect to the same piece of wire, the entire wire segment is one node, even if the physical connection points are separated.

Important distinction: A point where only two wires meet (one coming in, one going out with no split) is technically a node, but KCL applied there just says “current in equals current out”—which is trivially true and not particularly useful. KCL becomes powerful at junctions where current actually divides.

The Physical Basis: Conservation of Charge

KCL isn’t just a convenient mathematical rule—it’s a consequence of one of the most fundamental laws of physics: conservation of electric charge.

Charge cannot be created or destroyed: In any isolated system, the total electric charge remains constant. Charge can move from place to place (that’s current), but it cannot appear out of nowhere or vanish into nothingness.

Current is moving charge: Electric current is simply the flow rate of electric charge. One ampere equals one coulomb of charge flowing past a point per second.

Nodes don’t store charge (in DC circuits): In direct current (DC) circuits, nodes are just connection points—they don’t accumulate charge. Therefore, any charge (current) flowing in must immediately flow out.

The consequence: Since charge can’t be created, destroyed, or accumulated at a node, the rate at which charge flows in (current in) must equal the rate at which charge flows out (current out). This is KCL.

Analogy: Think of a node as a pipe junction with no storage tank. Water flowing in must equal water flowing out because water can’t accumulate in the junction and can’t disappear. Electric current behaves the same way at a node.

Sign Conventions

One source of confusion for beginners is handling current direction and signs. Here’s how to approach it systematically:

Method 1: Separate in and out

- Define currents flowing INTO the node as positive

- Define currents flowing OUT of the node as positive

- Then: ΣI_in = ΣI_out

Method 2: Unified sign convention

- Choose a reference direction for each current (an arrow on your diagram)

- Currents flowing INTO the node get a positive sign (+)

- Currents flowing OUT of the node get a negative sign (-)

- Then: ΣI = 0

Both methods are equivalent. Most engineers prefer Method 2 because it works uniformly regardless of how many currents you’re dealing with.

Important: The direction you initially assign to a current (your arrow) is just a reference—it doesn’t have to be the actual direction. If your calculated value comes out negative, it just means the actual current flows opposite to your assumed direction.

A Simple Example

Consider a node where three wires meet:

- Wire 1: 5A flowing INTO the node

- Wire 2: 2A flowing OUT of the node

- Wire 3: Unknown current, unknown direction

Applying KCL: Using the “in equals out” approach: Current in = Current out 5A = 2A + I₃ I₃ = 5A – 2A = 3A flowing OUT

Using the sign convention approach: ΣI = 0 (+5A) + (-2A) + (-I₃) = 0 I₃ = 3A (positive means our assumed direction was correct—flowing out)

Both methods give the same answer: 3A must flow out through wire 3.

This makes intuitive sense: 5A flows in, 2A flows out one path, so 3A must flow out the other path to balance.

The Mathematical Foundation of KCL

The General KCL Equation

For a node with n branches (wires) connected to it, KCL states:

Form 1 (separate in and out): I₁ + I₂ + … + Iₘ = Iₘ₊₁ + Iₘ₊₂ + … + Iₙ

Where I₁ through Iₘ are currents entering, and Iₘ₊₁ through Iₙ are currents leaving.

Form 2 (unified with signs): I₁ + I₂ + I₃ + … + Iₙ = 0

Where each current gets a + or – sign based on its direction relative to the node.

Form 3 (summation notation): Σᵢ₌₁ⁿ Iᵢ = 0

This is the most compact mathematical form, used in formal circuit analysis.

Applying KCL to Multiple Nodes

Real circuits have multiple nodes. KCL applies to every single node independently. If a circuit has 5 nodes, you can write 5 separate KCL equations.

However, one of these equations is always redundant (it can be derived from the others), so for a circuit with n nodes, you can write (n-1) independent KCL equations.

Why the redundancy? Because of overall charge conservation in the entire circuit. If you account for current at every node except one, the current at the last node is automatically determined.

Practical implication: When analyzing circuits, you typically don’t need to write KCL for every single node—just enough nodes to determine all unknown currents.

Relationship to Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law

Kirchhoff gave us two laws: Current Law (KCL) and Voltage Law (KVL). They’re complementary:

KCL (this article): Deals with currents at nodes (junctions) KVL (next article): Deals with voltages around loops

Together with Ohm’s Law, these two laws allow you to analyze any linear circuit, no matter how complex. They form the foundation of systematic circuit analysis techniques like nodal analysis and mesh analysis.

Think of them as two different lenses for viewing the same circuit:

- KCL focuses on “what happens at junctions?”

- KVL focuses on “what happens in closed paths?”

Both are necessary for complete circuit understanding.

From Physics to Engineering

The beautiful thing about KCL is that it connects fundamental physics (charge conservation) to practical engineering (circuit analysis):

Physics level: Charge is conserved in the universe. The total charge in any closed system remains constant.

Circuit level: At any node, charge flowing in must equal charge flowing out (because charge can’t accumulate or disappear at that point).

Mathematical level: This physical truth becomes the equation ΣI = 0, which we can use to solve for unknown currents.

Engineering level: This equation helps us design circuits, size components, troubleshoot problems, and predict behavior.

This progression from fundamental physical law to practical engineering tool is what makes circuit analysis so elegant and powerful.

Identifying Nodes in Real Circuits

Types of Nodes

Essential nodes (junctions): Points where three or more elements connect. These are the nodes where KCL provides useful information.

Example: Three resistor leads soldered together, or a point on a circuit board where multiple traces meet.

Simple connection points: Where only two elements connect. KCL still applies but trivially (in equals out for the same current).

Example: Two resistors connected end-to-end in series.

Reference node (ground): One node is typically chosen as the reference (0V). This is often the negative terminal of the power supply or the circuit’s ground connection.

Supernode: An advanced concept where two nodes are grouped together when a voltage source connects them. This is used in nodal analysis techniques.

Visualizing Nodes in Schematics

In circuit schematics, nodes are often indicated by:

Dots: A dot at a wire junction explicitly shows that wires connect there Continuous lines: Wires that merge without a break are connected Crossing wires without dots: In most conventions, wires that cross without a junction dot do NOT connect Named nodes: Important nodes might be labeled (VCC, GND, OUT, etc.)

Common beginner mistake: Assuming all intersecting lines in a schematic connect. Always look for junction dots or explicit labels.

Nodes in Physical Circuits

On actual circuit boards or breadboards:

Breadboard rails: An entire rail (row of connected holes) is a single node PCB copper pour: A continuous copper area is one node Wire segments: A piece of wire with no components in between is one node Solder joints: Points where multiple component leads are soldered together

Important: Physical distance doesn’t matter. A copper trace that meanders across a PCB but has no components interrupting it is still one node, even if it’s physically long.

Practice: Counting Nodes

Simple circuit: Battery connected to two resistors in parallel

- Node 1: Positive battery terminal and both resistor tops

- Node 2: Negative battery terminal and both resistor bottoms

- Total: 2 essential nodes

More complex circuit: Battery connected to three resistors—two in parallel, then one in series

- Node 1: Positive battery terminal and tops of parallel resistors

- Node 2: Bottoms of parallel resistors and top of series resistor

- Node 3: Bottom of series resistor and negative battery terminal

- Total: 3 essential nodes

The Reference Node Concept

When analyzing circuits, we often choose one node as the “reference” and measure all voltages relative to it:

Why it helps: Voltages are always differences between two points. Choosing a reference lets us talk about “the voltage at node A” meaning “voltage at node A relative to reference.”

Common choice: The negative terminal of the power supply or circuit ground becomes the reference, assigned 0V.

Effect on KCL: The choice of reference node doesn’t affect KCL equations at all—KCL deals with currents, not voltages. But it helps organize the overall circuit analysis.

Step-by-Step: Applying KCL to Simple Circuits

Example 1: Three-Branch Parallel Circuit

The Circuit: A 12V battery connected to three resistors in parallel:

- R₁ = 12Ω

- R₂ = 24Ω

- R₃ = 8Ω

Question: Find the current through each resistor and the total current from the battery.

Step 1: Identify the nodes

- Node A: Positive terminal of battery and tops of all three resistors

- Node B: Negative terminal of battery and bottoms of all three resistors

Step 2: Find currents through each resistor using Ohm’s Law All resistors have 12V across them (parallel configuration):

I₁ = V ÷ R₁ = 12V ÷ 12Ω = 1A I₂ = V ÷ R₂ = 12V ÷ 24Ω = 0.5A I₃ = V ÷ R₃ = 12V ÷ 8Ω = 1.5A

Step 3: Apply KCL at Node A Current from battery (I_total) flows IN Currents through R₁, R₂, R₃ flow OUT

Using KCL: ΣI = 0 I_total – I₁ – I₂ – I₃ = 0 I_total = I₁ + I₂ + I₃ I_total = 1A + 0.5A + 1.5A = 3A

Verification at Node B: Currents through R₁, R₂, R₃ flow IN Current back to battery flows OUT

Using KCL: I₁ + I₂ + I₃ – I_total = 0 I₁ + I₂ + I₃ = I_total 1A + 0.5A + 1.5A = 3A ✓

The analysis is consistent!

Example 2: Series-Parallel Combination

The Circuit:

- 9V battery

- R₁ = 100Ω in series with the battery

- R₂ = 200Ω and R₃ = 300Ω in parallel after R₁

Question: Find all branch currents.

Step 1: Identify nodes

- Node 1: Positive battery terminal and top of R₁

- Node 2: Bottom of R₁, tops of R₂ and R₃ (junction where current splits)

- Node 3: Bottoms of R₂ and R₃, negative battery terminal

Step 2: Find parallel resistance of R₂ and R₃ R_parallel = (R₂ × R₃) ÷ (R₂ + R₃) R_parallel = (200Ω × 300Ω) ÷ (200Ω + 300Ω) R_parallel = 60,000 ÷ 500 = 120Ω

Step 3: Find total current (through R₁) R_total = R₁ + R_parallel = 100Ω + 120Ω = 220Ω I₁ = V ÷ R_total = 9V ÷ 220Ω ≈ 0.0409A ≈ 41mA

Step 4: Find voltage at Node 2 Voltage drop across R₁: V_R1 = I₁ × R₁ = 0.0409A × 100Ω = 4.09V

Voltage at Node 2: V_node2 = 9V – 4.09V = 4.91V

Step 5: Find currents through parallel resistors I₂ = V_node2 ÷ R₂ = 4.91V ÷ 200Ω ≈ 0.0246A ≈ 24.6mA I₃ = V_node2 ÷ R₃ = 4.91V ÷ 300Ω ≈ 0.0164A ≈ 16.4mA

Step 6: Verify with KCL at Node 2 Current I₁ flows IN from R₁ Currents I₂ and I₃ flow OUT to R₂ and R₃

KCL: I₁ = I₂ + I₃ 41mA ≟ 24.6mA + 16.4mA 41mA ≈ 41mA ✓

Perfect! (Small rounding differences are expected)

Example 3: Four-Branch Junction

The Circuit: A node where four wires meet:

- Wire A: 8A flowing IN

- Wire B: 3A flowing OUT

- Wire C: 2A flowing IN

- Wire D: Unknown current and direction

Question: Find the current in Wire D.

Step 1: Set up KCL with sign convention Currents IN are positive, currents OUT are negative:

ΣI = 0 I_A + I_B + I_C + I_D = 0 (+8A) + (-3A) + (+2A) + I_D = 0

Step 2: Solve for I_D 8A – 3A + 2A + I_D = 0 7A + I_D = 0 I_D = -7A

Step 3: Interpret the result The negative sign means I_D flows in the opposite direction to our assumption. Since we assumed it as a variable without direction, the negative result means:

Wire D carries 7A flowing OUT of the node.

Verification: Current IN: 8A + 2A = 10A Current OUT: 3A + 7A = 10A IN = OUT ✓

This makes intuitive sense: 10A enters the node through wires A and C, and 10A leaves through wires B and D.

Practical Applications of KCL

Application 1: Designing Parallel LED Circuits

The Scenario: You want to power 9 LEDs from a 5V supply. For reliability, you design three parallel branches with three LEDs in series per branch. Each LED draws 15mA when properly lit.

Using KCL to determine supply current:

Step 1: Identify the node Node is the positive supply rail where current splits into three branches.

Step 2: Determine branch currents Each branch has LEDs in series, so current through each branch: I_branch = 15mA (same current through all series components)

Step 3: Apply KCL I_supply = I_branch1 + I_branch2 + I_branch3 I_supply = 15mA + 15mA + 15mA = 45mA

Design decisions based on this:

- Power supply must provide at least 45mA

- USB port (500mA max) is more than adequate

- Small coin cell battery (100mA typical) would work

- 78L05 voltage regulator (100mA max) would work

Extension: If one branch has two LEDs instead of three: That branch draws slightly more current (lower total voltage drop across LEDs means more across resistor, slightly higher current—maybe 16-17mA).

KCL at the supply node becomes: I_supply = 15mA + 15mA + 17mA = 47mA

Application 2: Troubleshooting Unbalanced Currents

The Scenario: You’ve built a circuit with three identical parallel resistors (1kΩ each) across a 12V supply. Theory says each should draw 12mA, for a total of 36mA. But your ammeter shows the supply delivering 48mA.

Using KCL to diagnose:

Step 1: Apply KCL at the supply node I_supply = I_R1 + I_R2 + I_R3 48mA = I_R1 + I_R2 + I_R3

Step 2: Measure individual branch currents Suppose measurements show:

- I_R1 = 12mA (correct)

- I_R2 = 12mA (correct)

- I_R3 = ?

Step 3: Use KCL to find I_R3 48mA = 12mA + 12mA + I_R3 I_R3 = 48mA – 24mA = 24mA

Step 4: Analyze the problem R3 is drawing twice the expected current. Possible causes:

- Wrong resistor value installed (maybe 500Ω instead of 1kΩ)

- Solder bridge creating a parallel path

- Damaged resistor with lower resistance

Verification using Ohm’s Law: If I_R3 = 24mA at V = 12V: R_actual = V ÷ I = 12V ÷ 0.024A = 500Ω

Indeed, R3 is 500Ω, not 1kΩ. Replace it with the correct value.

Application 3: Current Sensing and Monitoring

The Scenario: You’re monitoring power consumption in a circuit with three subsystems. Each has a current sensor (shunt resistor). The readings are:

- Subsystem A: 1.2A

- Subsystem B: 0.8A

- Subsystem C: 0.5A

Using KCL to verify power supply current:

All three subsystems connect to the same power rail (node), so: I_total = I_A + I_B + I_C I_total = 1.2A + 0.8A + 0.5A = 2.5A

Your power supply must provide at least 2.5A. If using a 3A-rated supply, you have 500mA margin (20%) which is reasonable.

If one subsystem is disabled: Suppose subsystem C is turned off (I_C = 0A): I_total = 1.2A + 0.8A + 0A = 2.0A

This shows how current demand changes with operating conditions.

Application 4: Battery Life Estimation with Multiple Loads

The Scenario: A portable device has a 2000mAh battery and three components:

- Microcontroller: 50mA continuous

- Display: 100mA when on (50% duty cycle → average 50mA)

- Radio: 200mA during transmission (10% duty cycle → average 20mA)

Using KCL to find total current draw:

At the battery node, current splits to all three loads: I_battery = I_micro + I_display_avg + I_radio_avg I_battery = 50mA + 50mA + 20mA = 120mA average

Battery life calculation: Runtime = Capacity ÷ Current Runtime = 2000mAh ÷ 120mA ≈ 16.7 hours

But apply real-world derating (~70% capacity at this discharge rate): Actual runtime ≈ 16.7 hours × 0.7 ≈ 11.7 hours

Application 5: Grounding and Return Current Paths

The Scenario: Three circuits share a common ground wire. Each circuit returns different currents to ground:

- Circuit 1: 2A

- Circuit 2: 1.5A

- Circuit 3: 0.8A

Using KCL at the ground node:

All three return currents merge at the ground node, then flow back to the power supply through one ground wire:

I_ground_wire = I_circuit1 + I_circuit2 + I_circuit3 I_ground_wire = 2A + 1.5A + 0.8A = 4.3A

Important design considerations: The shared ground wire must carry 4.3A safely. Using wire ampacity tables:

- 22 AWG: 7A max (insufficient margin)

- 20 AWG: 11A max (better)

- 18 AWG: 16A max (good margin)

Choose 18 AWG or 20 AWG for the common ground return.

Voltage drop analysis: If using 20 AWG (0.0331Ω/m) and ground wire is 2m long: R_ground = 2m × 0.0331Ω/m = 0.0662Ω V_drop = I × R = 4.3A × 0.0662Ω ≈ 0.285V

This 285mV drop in the ground path could affect sensitive circuits. For precision work, use thicker wire (lower resistance) or separate ground returns.

KCL in Complex Circuit Analysis

Nodal Analysis: A Systematic Approach

Nodal analysis is a formal technique that uses KCL systematically to solve complex circuits. It’s one of the most powerful circuit analysis methods.

The process:

Step 1: Choose a reference node (ground) Usually the negative terminal of the main power supply.

Step 2: Label all other nodes Assign names or numbers (A, B, C or 1, 2, 3) to all essential nodes.

Step 3: Assign node voltages Each node has a voltage (V₁, V₂, V₃) relative to the reference node.

Step 4: Write KCL equations for each non-reference node Express all currents in terms of node voltages using Ohm’s Law.

Step 5: Solve the system of equations Use algebra or matrix methods to find all node voltages.

Step 6: Calculate branch currents Once you know node voltages, use Ohm’s Law to find currents.

Example: Three-Node Circuit

The Circuit:

- 12V source between Node 0 (ground) and Node 1

- R₁ = 100Ω between Node 1 and Node 2

- R₂ = 200Ω between Node 2 and ground

- R₃ = 300Ω between Node 1 and ground

Step 1: Node equations

At Node 1 (V₁ = 12V, known from voltage source): No need to write KCL; voltage is given.

At Node 2: Currents entering Node 2:

- From R₁: I₁ = (V₁ – V₂) ÷ R₁ = (12 – V₂) ÷ 100

Currents leaving Node 2:

- Through R₂: I₂ = V₂ ÷ R₂ = V₂ ÷ 200

KCL at Node 2: I₁ = I₂ (12 – V₂) ÷ 100 = V₂ ÷ 200

Step 2: Solve for V₂ Multiply both sides by 200: 2(12 – V₂) = V₂ 24 – 2V₂ = V₂ 24 = 3V₂ V₂ = 8V

Step 3: Find all currents I₁ = (12V – 8V) ÷ 100Ω = 4V ÷ 100Ω = 0.04A = 40mA I₂ = 8V ÷ 200Ω = 0.04A = 40mA I₃ = 12V ÷ 300Ω = 0.04A = 40mA

Verification at Node 1: Current from source flows IN I₁ and I₃ flow OUT

I_source = I₁ + I₃ = 40mA + 40mA = 80mA

Total circuit current = 80mA ✓

When Circuits Have Current Sources

Current sources complicate KCL slightly because their current is fixed regardless of voltage.

Example: Node with:

- 2A current source flowing IN

- Resistor (unknown current) flowing OUT to ground

- Another resistor (unknown current) flowing OUT to another node

KCL equation: 2A = I_R1 + I_R2

The current source provides exactly 2A, which divides between the two resistors according to their resistances (current divider principle).

Supernodes: Handling Voltage Sources Between Nodes

When a voltage source connects two non-reference nodes, nodal analysis uses a “supernode” technique:

The concept: Treat the two nodes connected by the voltage source as one “supernode” and write KCL for the combined node, ignoring the current through the voltage source.

Then add a constraint equation from the voltage source: V_nodeA – V_nodeB = V_source

This gives you the equations needed to solve for both node voltages.

Why this works: The voltage source enforces a fixed voltage difference between the two nodes, and KCL still applies to the combined system (current in equals current out of the supernode).

Common Mistakes and Misconceptions

Mistake 1: Confusing Nodes and Loops

The error: Applying KCL around a loop instead of at a node, or mixing up current and voltage relationships.

The truth:

- KCL applies to NODES (junctions): ΣI = 0

- KVL applies to LOOPS (closed paths): ΣV = 0

How to avoid it: Always identify clearly whether you’re analyzing a junction (use KCL) or a loop (use KVL, covered in the next article).

Mistake 2: Incorrect Sign Assignment

The error: Mixing up signs when writing KCL equations, leading to wrong answers.

Example of error: Node with 5A in and 2A and 3A out: Wrong: 5A + 2A + 3A = 0 Right: 5A – 2A – 3A = 0 (using in as + and out as -) Or right: 5A = 2A + 3A (separating in and out)

How to avoid it:

- Choose a sign convention and stick to it consistently

- Draw arrows on your diagram showing assumed current directions

- Double-check that your equation makes physical sense

Mistake 3: Forgetting About Hidden Currents

The error: Writing KCL without accounting for all currents entering or leaving a node.

Example: A node where three resistors meet. You write: I₁ + I₂ + I₃ = 0

But you forgot that this node also connects to a power supply, so there’s actually a fourth current from the supply!

How to avoid it: Carefully trace every wire connected to the node. Don’t assume—verify that you’ve accounted for all paths.

Mistake 4: Misidentifying Nodes

The error: Treating separate nodes as one node, or separating what should be one continuous node.

Common scenario: Two points on a long wire with no components between them—these are the same node, even if physically separated.

Or: Two wires that cross in a schematic but don’t connect (no junction dot)—these are NOT the same node.

How to avoid it:

- In schematics, look for junction dots or explicit connection indicators

- In physical circuits, trace the copper/wire continuity

- When in doubt, use a multimeter in continuity mode to verify if two points are electrically connected

Mistake 5: Applying KCL to Components Instead of Nodes

The error: Trying to apply KCL to a component (like a resistor) rather than to a junction point.

Example: “The current into the resistor equals the current out” is true but trivial—it’s just saying the same current flows through the whole resistor, not a useful application of KCL.

The truth: KCL is useful at nodes where current actually splits or combines. For a single component, current in equals current out automatically.

How to avoid it: Focus KCL analysis on junction points where three or more elements meet.

Mistake 6: Ignoring Current Direction Reality

The error: Getting a negative answer for current and thinking you made a mistake.

The truth: Negative current just means the actual direction is opposite your assumed direction. This is perfectly normal and valid!

Example: You assume I₁ flows left-to-right, calculate I₁ = -3A. This means I₁ actually flows right-to-left at 3A.

How to avoid confusion:

- Remember that initial current direction is just an assumption

- Negative results are valid—just reinterpret the direction

- Verify your final answer makes physical sense (currents should balance)

Mistake 7: Unit Inconsistency

The error: Mixing units (mA with A, µA with mA) in KCL equations.

Example: I_total = 2A + 500mA + 100µA Without conversion: 2 + 500 + 100 = 602 (nonsense!) With conversion: 2A + 0.5A + 0.0001A = 2.5001A ✓

How to avoid it:

- Convert all currents to the same unit before adding

- Usually convert to amperes (A) for consistency

- Or convert to the most convenient unit (mA if all currents are in that range)

Advanced Topics and Extensions

AC Circuits and Complex Currents

In alternating current (AC) circuits, KCL still applies, but currents are represented as complex numbers (phasors) because they vary sinusoidally with time.

The principle remains the same: ΣI = 0 at every node

But currents are complex: I = I_magnitude × e^(jωt + φ)

Where:

- I_magnitude is the current amplitude

- ω is angular frequency

- φ is phase angle

- j is the imaginary unit

Practical meaning: At any instant in time, KCL is satisfied. Over time, currents vary, but at each moment, charge conservation still holds.

Example: Node with:

- I₁ = 5∠0° A (5A at 0° phase)

- I₂ = 3∠90° A (3A at 90° phase)

- I₃ = unknown

KCL (using phasor addition): I₁ + I₂ + I₃ = 0

Convert to rectangular form: I₁ = 5 + j0 I₂ = 0 + j3 I₁ + I₂ = 5 + j3

Therefore: I₃ = -(5 + j3) = -5 – j3

Magnitude: |I₃| = √(5² + 3²) = √34 ≈ 5.83A Phase: φ₃ = arctan(-3/-5) ≈ -149° (third quadrant)

Transient Analysis

During transients (circuit switches on/off, sudden changes), KCL still applies at every instant:

Capacitors: I_C = C × dV/dt The current through a capacitor depends on how fast voltage changes.

Inductors: V_L = L × dI/dt The voltage across an inductor depends on how fast current changes.

KCL with capacitors and inductors: At a node with capacitors or inductors, KCL becomes a differential equation because currents involve derivatives.

Example: Node with resistor (I_R) and capacitor (I_C) to ground: I_source = I_R + I_C I_source = V/R + C × dV/dt

This is a differential equation that describes how voltage at the node changes over time.

KCL at High Frequencies

At very high frequencies (RF, microwave), parasitic effects become significant:

Parasitic capacitance: Every node has small capacitance to ground/other nodes Parasitic inductance: Every wire has small inductance Electromagnetic radiation: At very high frequencies, circuits can radiate energy

Modified KCL: At high frequencies, KCL must account for displacement current (current through capacitance) and sometimes radiation losses.

For most practical electronics below ~100 MHz, standard KCL applies without modification.

Quantum Circuits and the Limits of KCL

At extremely small scales (nanometers) and low temperatures, quantum effects appear:

Single-electron transistors: Current flows one electron at a time Quantum dots: Electrons are quantized Superconducting circuits: Zero resistance, quantum coherence

Does KCL still apply? In a time-averaged sense, yes—charge conservation holds even in quantum systems. But instantaneously, current might be “lumpy” (discrete electrons) rather than continuous.

For practical electronics engineering, these quantum effects are negligible, and KCL applies universally.

Practical Problem-Solving Strategies

Strategy 1: The Systematic Node-by-Node Approach

When to use: Circuits with multiple nodes and unknown currents

Process:

- Number all nodes (choose one as reference)

- Write KCL for each non-reference node

- Express currents in terms of node voltages using Ohm’s Law

- Solve the system of equations

- Calculate branch currents from node voltages

Example application: Power distribution network with multiple loads

Strategy 2: The Current-Tracing Method

When to use: Troubleshooting or when you know some currents and need to find others

Process:

- Start at a node where you know all but one current

- Apply KCL to find the unknown current

- Move to the next node where you now know all but one current

- Repeat until all currents are known

Example application: Finding the fault current in a circuit with a suspected short

Strategy 3: The Symmetry Shortcut

When to use: Circuits with symmetrical structure

Process:

- Identify symmetrical elements (identical components in identical positions)

- Recognize that symmetrical elements carry identical currents

- Use this to simplify KCL equations

Example application: Wheatstone bridge in balanced condition, where center current is zero by symmetry

Strategy 4: The Limiting Case Check

When to use: Verifying complex circuit analysis

Process:

- Consider extreme cases (resistor becomes open or short)

- Check if your KCL solution makes sense in these limits

- If limits don’t make sense, recheck your analysis

Example: If R → ∞ (open circuit), current through that branch should → 0 If R → 0 (short circuit), current through that branch should → maximum

Combining KCL with Other Tools

KCL + Ohm’s Law: The most common combination. KCL gives current relationships, Ohm’s Law relates currents to voltages and resistances.

KCL + KVL: Together they allow complete circuit analysis. KCL at nodes, KVL around loops.

KCL + Power equations: Once currents are known from KCL, calculate power: P = V × I or P = I² × R

KCL + Thevenin/Norton: Use KCL to find short-circuit current (Norton current) or to verify Thevenin equivalent circuits.

Comparison Table: KCL vs. Related Circuit Laws

| Aspect | Kirchhoff’s Current Law (KCL) | Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL) | Ohm’s Law | Conservation of Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What it describes | Current conservation at nodes | Voltage conservation around loops | V-I-R relationship | Energy conservation in circuits |

| Physical basis | Conservation of electric charge | Conservation of energy | Material resistivity | First law of thermodynamics |

| Mathematical form | ΣI = 0 at any node | ΣV = 0 around any loop | V = I × R | P_in = P_out + P_dissipated |

| Where it applies | Junction points (nodes) | Closed loops (meshes) | Individual components | Entire circuits or components |

| Primary use | Finding unknown currents | Finding unknown voltages | Relating V, I, and R | Power budget analysis |

| Sign convention | IN positive, OUT negative (or vice versa) | Voltage rise positive, drop negative | Fixed relationship | Energy in positive, out negative |

| Works in AC circuits? | Yes (with phasors/complex notation) | Yes (with phasors/complex notation) | Yes (with impedance Z instead of R) | Yes (with reactive power) |

| Exceptions/limitations | None in lumped circuits | None in lumped circuits | Only for ohmic materials | None (universal law) |

| Typical units | Amperes (A) | Volts (V) | V, A, Ω | Watts (W) or Joules (J) |

| Beginner difficulty | Medium | Medium | Easy | Medium to Hard |

| Independence | Independent law | Independent law | Independent law | Derived from power relationships |

Conclusion: Mastering Current Conservation

Kirchhoff’s Current Law stands as one of the foundational principles of circuit analysis, right alongside Ohm’s Law and Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law. Its beauty lies in its simplicity: charge doesn’t appear or disappear at circuit junctions, so current in must equal current out.

Why KCL Matters

For circuit design: KCL helps you calculate how current distributes among parallel branches, size wires and components appropriately, and ensure power supplies can deliver needed current.

For troubleshooting: When measured currents don’t balance at a node, KCL immediately tells you something is wrong—a short circuit, wrong component value, or measurement error.

For understanding: KCL develops your intuition about current flow. After working with it extensively, you’ll start to “see” how current must flow in a circuit, even before doing calculations.

For advanced analysis: Nodal analysis, one of the most powerful circuit analysis techniques, is built entirely on systematic application of KCL at every node.

From Physical Law to Practical Tool

The progression from fundamental physics to practical engineering tool is what makes circuit analysis so elegant:

Physics: Charge is conserved in the universe Circuit theory: Charge doesn’t accumulate at ideal nodes Mathematics: ΣI = 0 at every node Engineering: We can calculate unknown currents and design functional circuits

This connection ensures that our circuit analysis isn’t just mathematical abstraction—it’s grounded in physical reality.

Beyond DC Circuits

While we’ve focused mainly on DC circuits in this article, KCL’s universality extends far beyond:

- AC power systems: KCL applies to power distribution networks

- Signal processing: Audio and RF circuits obey KCL

- Digital circuits: Even fast logic signals respect current conservation

- Mixed circuits: Combined analog-digital systems use KCL throughout

The form might become more complex (phasors, complex impedances), but the fundamental principle—current conservation at nodes—remains unchanged.

Building Your Skills

Mastering KCL requires:

Conceptual understanding: Know why it’s true (charge conservation) and when it applies (everywhere in lumped circuits)

Problem-solving practice: Work through diverse examples until setting up KCL equations becomes automatic

Circuit intuition: Develop the ability to estimate current distributions before calculating

Integration with other tools: Learn to combine KCL with Ohm’s Law, KVL, and power equations for complete circuit analysis

Your Next Steps

Now that you understand Kirchhoff’s Current Law:

- Practice identifying nodes in various circuits—schematics and physical layouts

- Work through problems with increasing complexity, from simple parallel circuits to complex multi-node networks

- Verify with measurements when possible—build circuits and confirm that measured currents balance at nodes

- Move to KVL (the next article) to complete your understanding of Kirchhoff’s Laws

- Learn nodal analysis as a systematic way to apply KCL to complex circuits

The Complementary Pair

KCL and KVL are complementary tools:

- KCL focuses on junctions and currents

- KVL focuses on loops and voltages

Together, they provide complete information about circuit behavior. Master both, and you can analyze any linear circuit, no matter how complex.

Final Thought

Kirchhoff’s Current Law, first formulated in 1845, remains as relevant today as it was nearly 180 years ago. Whether Gustav Kirchhoff was analyzing telegraph circuits or whether modern engineers are designing smartphone power management systems, the same fundamental principle applies: at any junction, what goes in must come out.

This timeless truth, rooted in the conservation of electric charge, continues to guide circuit design, analysis, and troubleshooting. It’s a testament to the power of understanding fundamental physical principles—they don’t become obsolete with changing technology.

Master KCL, and you’ve gained a tool that will serve you throughout your entire electronics journey, from your first LED circuit to the most complex systems you’ll ever design.

Current conservation at nodes: ΣI = 0. Simple equation. Profound implications. Universal application.