Introduction

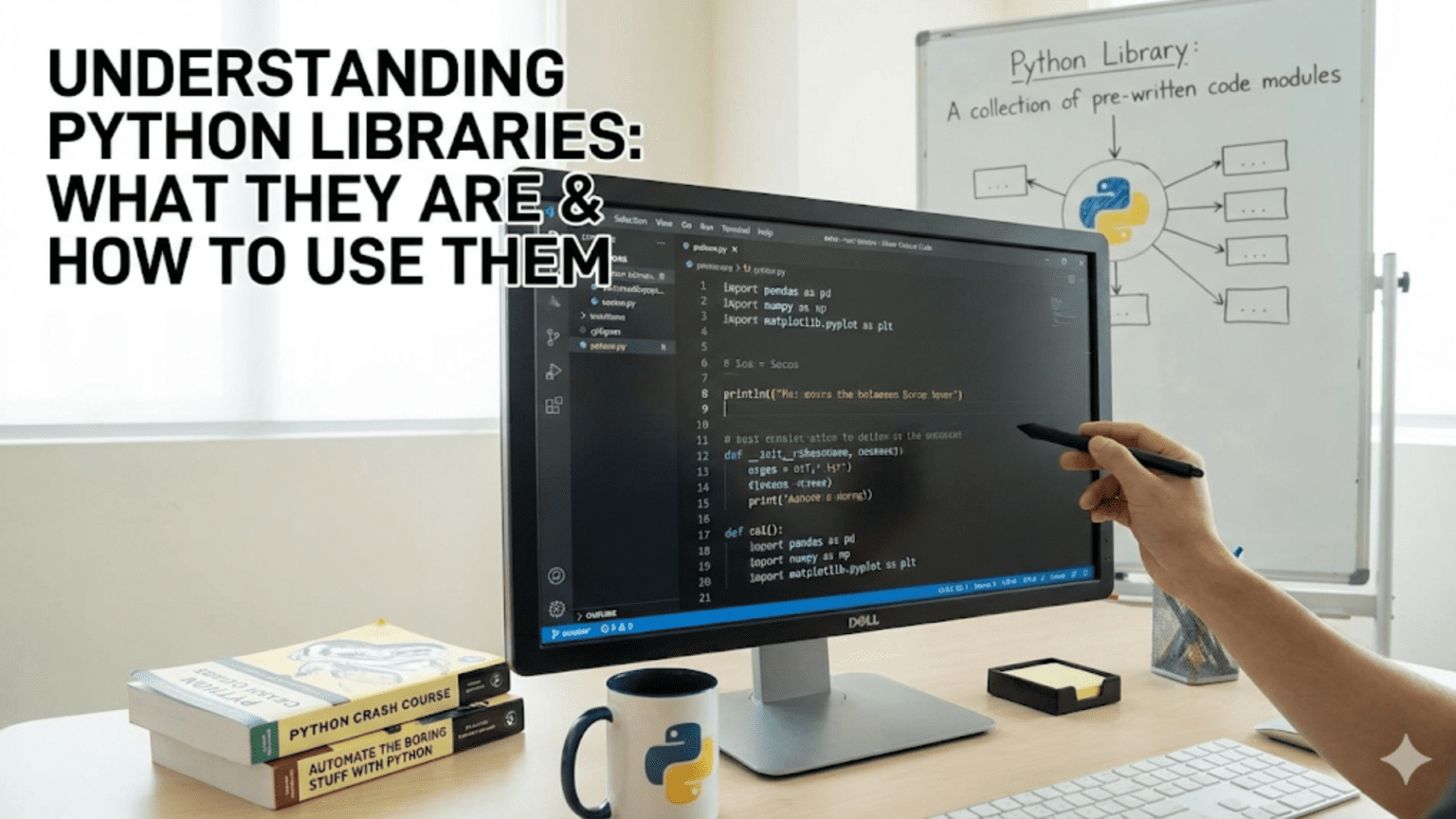

After learning Python’s fundamental syntax including variables, loops, functions, and data structures, you might notice that many common tasks still require substantial code. Calculating advanced statistics, reading different file formats, creating visualizations, or working with dates all demand considerable programming effort if you build everything from scratch. This is where Python libraries come to your rescue, providing pre-written, tested code that solves common problems so you can focus on your specific analysis rather than reinventing solutions to universal challenges.

Python libraries represent collections of code that others have written and shared for everyone to use. Think of them as toolboxes containing specialized tools for specific tasks. Just as a carpenter does not forge their own hammer but selects the right tool from their toolbox, programmers do not write every function from scratch but import appropriate libraries that provide needed functionality. For data science, libraries like NumPy handle numerical computations, pandas manages tabular data, matplotlib creates visualizations, and scikit-learn implements machine learning algorithms. These libraries save countless hours of development time while providing robust, efficient implementations that have been refined through years of community use.

Understanding libraries fundamentally changes your relationship with Python programming. Instead of viewing Python as just the language features you have learned so far, you begin seeing it as an ecosystem where the core language provides syntax and basic functionality while libraries extend capabilities infinitely. This ecosystem approach explains Python’s dominance in data science: while the language itself is relatively simple, the rich library ecosystem enables virtually any analytical task. Learning to find, install, import, and use libraries effectively represents a crucial step in your evolution from beginner to productive data scientist.

This comprehensive guide demystifies Python libraries from the ground up. You will learn what libraries, modules, and packages are and how they relate to each other, how to import functionality using various import statements, what the Python Standard Library includes and why it matters, how third-party libraries extend Python’s capabilities, and best practices for organizing imports and using libraries effectively. You will also discover how to read documentation, explore library contents, and troubleshoot common import issues. By the end, you will confidently incorporate libraries into your code, dramatically expanding what you can accomplish with Python.

What Are Modules, Packages, and Libraries?

Before diving into how to use libraries, understanding the terminology prevents confusion. The terms module, package, and library are related but distinct, and using them correctly helps you understand documentation and discussions about Python code.

A module is simply a Python file containing definitions and statements. When you save code in a file with a .py extension, you have created a module. For example, if you create a file named statistics_helpers.py containing useful statistical functions, that file is a module:

# statistics_helpers.py

def calculate_mean(numbers):

return sum(numbers) / len(numbers)

def calculate_median(numbers):

sorted_nums = sorted(numbers)

n = len(sorted_nums)

if n % 2 == 0:

return (sorted_nums[n//2 - 1] + sorted_nums[n//2]) / 2

return sorted_nums[n//2]Other Python files can import and use functions from this module, avoiding code duplication and promoting reusability.

A package is a collection of related modules organized in a directory hierarchy. Packages let you structure large codebases logically by grouping related modules together. For instance, a data analysis package might contain separate modules for cleaning, visualization, and statistical tests. Python identifies directories as packages when they contain a special file named __init__.py, which can be empty or contain initialization code.

A library typically refers to a collection of packages and modules designed to accomplish related tasks. While Python documentation sometimes uses “library” and “package” interchangeably, in common usage, a library represents the entire distribution you install and import. For example, pandas is a library that contains multiple packages and modules working together to provide DataFrame functionality. When people say “import the pandas library,” they mean importing the pandas package and its constituent modules.

The Python Standard Library deserves special mention as the collection of modules distributed with Python itself, requiring no separate installation. It includes modules for file I/O, mathematics, date and time operations, internet protocols, and much more. You have already used parts of the Standard Library whenever you called print() or used built-in types like lists and dictionaries, though these fundamental features do not require explicit imports.

Understanding this hierarchy matters when reading documentation or error messages. When you see “ImportError: No module named pandas,” you know you are trying to import a module or package that Python cannot find. When documentation refers to the statistics module, you understand it is a single file of related functions, while the NumPy library encompasses multiple modules and packages providing comprehensive numerical computing capabilities.

The Import Statement: Bringing Libraries into Your Code

The import statement makes library functionality available in your Python programs. The simplest form imports an entire module or package:

import math

# Now you can use math functions

result = math.sqrt(16)

print(result) # 4.0

circle_area = math.pi * (5 ** 2)

print(circle_area) # 78.53981633974483After importing math, you access its contents using dot notation: module_name.function_name. This explicit naming prevents conflicts if multiple modules provide functions with the same names.

You can import specific items from a module using the from keyword:

from math import sqrt, pi

# Now use them directly without the math prefix

result = sqrt(16)

circle_area = pi * (5 ** 2)This approach lets you use imported names directly but requires listing each item explicitly. It works well when you need only a few functions from a large module.

Import everything from a module using the asterisk wildcard:

from math import *

# All math functions and constants are now available

result = sqrt(16)

angle = sin(pi / 2)However, wildcard imports are discouraged because they make code less readable and can cause naming conflicts. You cannot easily tell which functions come from which module when reading the code, and imported names might override variables you define elsewhere. Use explicit imports instead.

The as keyword lets you create aliases for imported modules or functions, useful for long names or conventional abbreviations:

import numpy as np # Standard NumPy alias

import pandas as pd # Standard pandas alias

# Now use shorter aliases

array = np.array([1, 2, 3])

dataframe = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1, 2, 3]})The data science community has established conventions for these aliases. Always use np for NumPy, pd for pandas, plt for matplotlib.pyplot, and similar standard abbreviations. This consistency makes code readable across projects and documentation.

You can also alias specific imports:

from datetime import datetime as dt

# Use the alias

now = dt.now()

print(now)Import multiple items on separate lines for clarity:

# Less clear

from math import sqrt, sin, cos, pi, e

# Clearer

from math import sqrt, sin, cos

from math import pi, eOr use parentheses for multi-line imports:

from math import (

sqrt, sin, cos,

pi, e

)Exploring the Python Standard Library

The Python Standard Library provides extensive functionality without requiring any installation beyond Python itself. Understanding what the Standard Library offers prevents you from reinventing solutions to common problems.

The math module provides mathematical functions beyond basic arithmetic:

import math

# Trigonometric functions

print(math.sin(math.pi / 2)) # 1.0

print(math.cos(0)) # 1.0

# Logarithms and exponentials

print(math.log(10)) # Natural log

print(math.log10(100)) # Base 10 log: 2.0

print(math.exp(1)) # e^1: 2.718...

# Other useful functions

print(math.factorial(5)) # 120

print(math.ceil(4.2)) # 5

print(math.floor(4.8)) # 4The random module generates random numbers and selections:

import random

# Random float between 0 and 1

print(random.random())

# Random integer in range

print(random.randint(1, 100))

# Random choice from list

colors = ['red', 'blue', 'green']

print(random.choice(colors))

# Shuffle a list in place

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

random.shuffle(numbers)

print(numbers)

# Random sample without replacement

sample = random.sample(range(100), 5)

print(sample)The datetime module handles dates and times:

from datetime import datetime, date, timedelta

# Current date and time

now = datetime.now()

print(now)

# Current date only

today = date.today()

print(today)

# Create specific dates

birthday = date(1990, 5, 15)

print(birthday)

# Date arithmetic

tomorrow = today + timedelta(days=1)

print(tomorrow)

next_week = today + timedelta(weeks=1)

print(next_week)

# Format dates as strings

formatted = now.strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

print(formatted)The statistics module provides basic statistical functions:

import statistics

data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

print(statistics.mean(data)) # 5.5

print(statistics.median(data)) # 5.5

print(statistics.mode([1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4])) # 3

print(statistics.stdev(data)) # Standard deviation

print(statistics.variance(data)) # VarianceThe json module works with JSON data:

import json

# Convert Python dictionary to JSON string

data = {'name': 'Alice', 'age': 30, 'city': 'Boston'}

json_string = json.dumps(data)

print(json_string) # '{"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}'

# Convert JSON string to Python dictionary

parsed = json.loads(json_string)

print(parsed['name']) # 'Alice'The collections module provides specialized container types:

from collections import Counter, defaultdict

# Count occurrences

words = ['apple', 'banana', 'apple', 'cherry', 'banana', 'apple']

counts = Counter(words)

print(counts) # Counter({'apple': 3, 'banana': 2, 'cherry': 1})

print(counts.most_common(2)) # [('apple', 3), ('banana', 2)]

# Dictionary with default values

dd = defaultdict(int) # Default value is 0

dd['count'] += 1

print(dd['count']) # 1

print(dd['other']) # 0 (automatic default)These modules represent just a fraction of the Standard Library, which also includes modules for regular expressions, file paths, CSV handling, HTTP requests, and much more. Familiarizing yourself with the Standard Library prevents reinventing functionality that already exists.

Third-Party Libraries: Extending Python’s Capabilities

While the Standard Library provides essential functionality, third-party libraries extend Python into specialized domains. For data science, several libraries have become indispensable.

NumPy provides efficient numerical computing with multi-dimensional arrays and mathematical operations. It forms the foundation for most scientific Python libraries:

import numpy as np

# Create arrays

array = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

print(array)

# Perform vectorized operations

doubled = array * 2

squared = array ** 2

print(doubled) # [ 2 4 6 8 10]

print(squared) # [ 1 4 9 16 25]

# Statistical operations

print(np.mean(array)) # 3.0

print(np.std(array)) # Standard deviationPandas provides DataFrame structures for tabular data manipulation, similar to Excel or SQL tables but with powerful Python integration:

import pandas as pd

# Create DataFrame

data = {

'Name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie'],

'Age': [25, 30, 35],

'City': ['Boston', 'Seattle', 'Chicago']

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print(df)

# Access columns

print(df['Name'])

# Filter rows

adults = df[df['Age'] > 25]

print(adults)Matplotlib creates static, animated, and interactive visualizations:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Simple line plot

x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

y = [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

plt.plot(x, y)

plt.title('Simple Line Plot')

plt.xlabel('X values')

plt.ylabel('Y values')

plt.show()Scikit-learn provides machine learning algorithms:

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

# Create and train model

model = LinearRegression()

X = [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]

y = [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

model.fit(X, y)

# Make predictions

predictions = model.predict([[6], [7]])

print(predictions) # Approximately [12, 14]These libraries work together seamlessly. You might load data with pandas, process it with NumPy, train models with scikit-learn, and visualize results with matplotlib, all within the same analysis.

How to Read Library Documentation

Learning to read documentation efficiently accelerates your mastery of new libraries. Most Python libraries follow similar documentation patterns.

Start with the library’s main documentation page, typically hosted on ReadTheDocs or the library’s website. Look for:

- Getting Started or Quickstart guides that introduce basic concepts

- Installation instructions

- Tutorials that walk through common use cases

- API Reference that details every function and class

When you encounter a new function, read its documentation string (docstring) using the help() function:

import math

help(math.sqrt)This displays the function’s signature, parameters, return value, and description. Many IDEs show this information automatically when you hover over function names or type opening parentheses.

Documentation typically includes:

- Function signature showing required and optional parameters

- Parameter descriptions explaining what each accepts

- Return value description

- Examples showing typical usage

- Notes about edge cases or important behaviors

For example, pandas documentation might show:

DataFrame.drop(labels=None, axis=0, columns=None, inplace=False)

Remove rows or columns by specifying label names and axis.

Parameters:

----------

labels : single label or list-like

Index or column labels to drop.

axis : {0 or 'index', 1 or 'columns'}, default 0

Whether to drop labels from index (0 or 'index') or columns (1 or 'columns').This tells you drop() can remove rows or columns, requires you to specify labels, and has optional parameters controlling behavior.

Best Practices for Using Libraries

Following established patterns makes your code more readable and maintainable.

Organize imports at the top of files in three groups, separated by blank lines:

- Standard Library imports

- Third-party library imports

- Local application imports

# Standard library

import math

import json

from datetime import datetime

# Third-party libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Local imports

from my_module import my_functionWithin each group, sort imports alphabetically for easy scanning.

Use standard aliases for common libraries:

import numpy as np # Not numpy as numpy or numpy as n

import pandas as pd # Not pandas as pandas or pandas as p

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Not matplotlib.pyplot as pyplotThese conventions are nearly universal in data science code, and following them makes your code immediately familiar to others.

Avoid wildcard imports in production code:

# Bad - unclear where names come from

from numpy import *

result = array([1, 2, 3])

# Good - explicit about source

import numpy as np

result = np.array([1, 2, 3])Import only what you need from large libraries:

# If you only need specific items

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

# Rather than importing the entire library

import sklearnUse absolute imports rather than relative imports for clarity:

# Clear

from my_package.data_processing import clean_data

# Less clear

from ..data_processing import clean_dataCommon Import Issues and How to Solve Them

Understanding common import problems helps you debug issues quickly.

ImportError or ModuleNotFoundError means Python cannot find the module:

import pandas # ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'pandas'Solutions:

- Verify the library is installed:

pip listshows installed packages - Install the library:

pip install pandas - Check you are using the correct Python environment

- Verify spelling in the import statement

Circular imports occur when two modules import each other:

# module_a.py

from module_b import function_b

# module_b.py

from module_a import function_a # Circular import!Solution: Restructure code to break the circular dependency or use imports inside functions rather than at module level.

Attribute errors mean the imported module does not contain what you expected:

import math

math.square(4) # AttributeError: module 'math' has no attribute 'square'Solutions:

- Check documentation for correct function names

- Verify you imported the right module

- Use dir(module) to see available attributes

Name shadowing happens when you name variables the same as modules:

math = 5 # Overwrites the math module!

import math

math.sqrt(16) # AttributeError: 'int' object has no attribute 'sqrt'Solution: Never use library names as variable names.

Conclusion

Python libraries transform Python from a programming language into a powerful ecosystem for data science and countless other applications. Understanding that libraries consist of modules and packages, knowing how to import them using various import statements, familiarizing yourself with the Standard Library, and learning to work with third-party libraries dramatically expands what you can accomplish with Python. Rather than writing everything from scratch, you leverage the work of thousands of developers who have solved common problems and shared their solutions.

The data science workflow relies almost entirely on libraries. You will use pandas for data manipulation, NumPy for numerical operations, matplotlib and seaborn for visualization, scikit-learn for machine learning, and dozens of other libraries for specialized tasks. Each library builds on Python’s core language, providing domain-specific functionality through intuitive interfaces. Learning to find appropriate libraries, read their documentation, and incorporate them into your code represents a crucial skill that separates beginners from productive practitioners.

As you continue your data science journey, you will encounter new libraries constantly. The process of learning each new library follows the same pattern: read introductory documentation, work through basic examples, consult API references for specific functions, and practice with real problems. The effort you invest now in understanding how libraries work, how imports function, and how to read documentation pays dividends every time you encounter a new tool. Master these library fundamentals, and you gain the ability to leverage the entire Python ecosystem, dramatically accelerating your productivity and capabilities as a data scientist.