Introduction

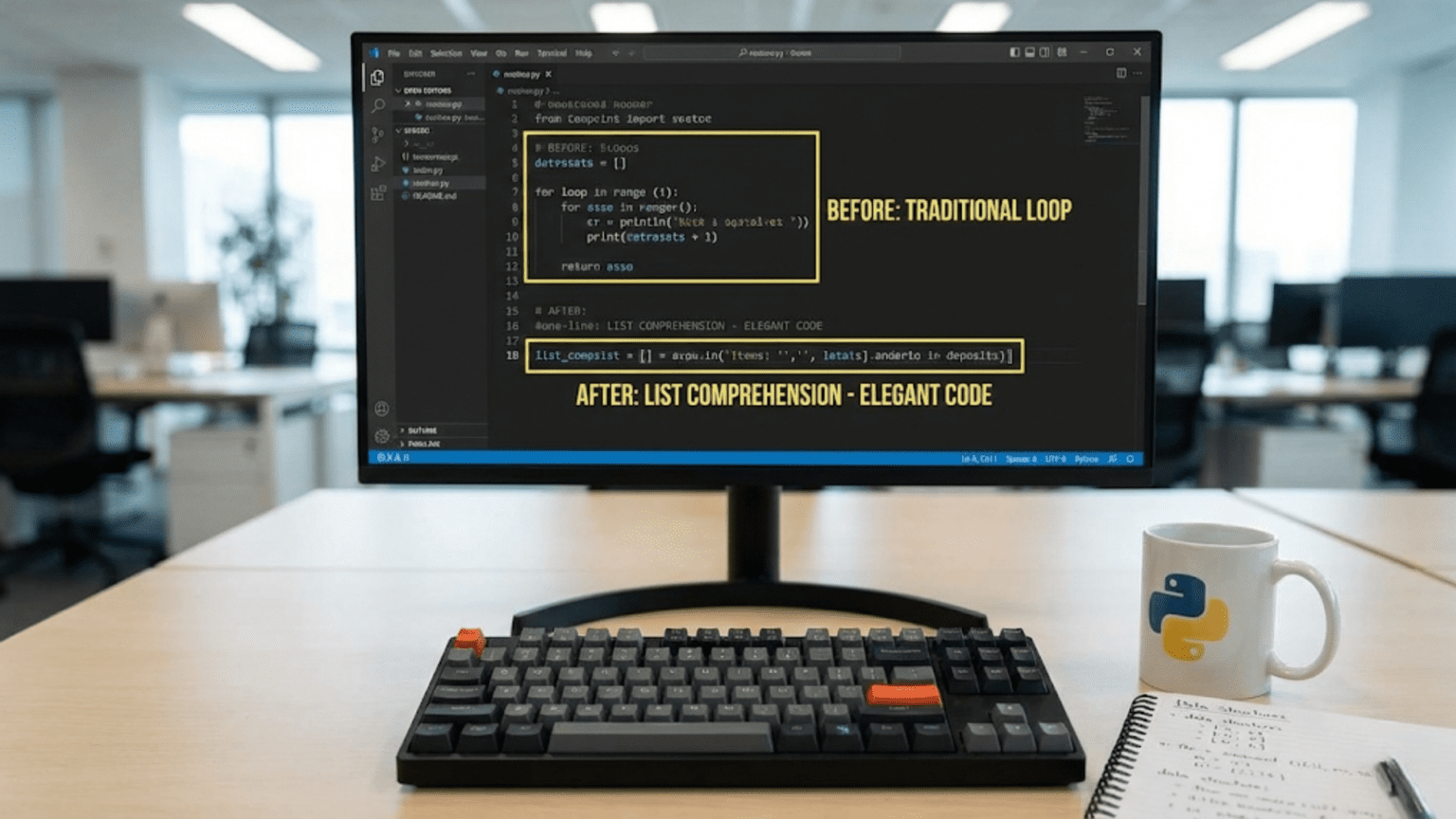

After mastering loops, you have the power to process collections systematically, transforming data, filtering values, and building new lists through iteration. However, the standard loop syntax requires multiple lines even for simple operations: initialize an empty list, write a for loop, append each transformed item, and finally use the result. This verbosity makes code longer than necessary and can obscure the actual logic beneath the boilerplate. List comprehensions solve this problem by condensing common loop patterns into single, readable expressions that clearly communicate your intent while often executing faster than equivalent loops.

List comprehensions represent one of Python’s most beloved features, distinguishing Pythonic code from code that simply happens to be written in Python. Where other languages require verbose iteration, Python lets you transform an entire list in one elegant line. This conciseness matters not just for aesthetics but for maintainability, as shorter code with less boilerplate contains fewer places for bugs to hide and makes the actual data transformations more obvious. When you see a list comprehension, you immediately recognize the pattern: “create a new list by applying this transformation to each item in that collection,” without parsing through multiple lines of loop mechanics.

For data scientists, list comprehensions become essential tools for data preprocessing and feature engineering. You might transform a list of temperatures from Fahrenheit to Celsius, filter a list of observations to exclude outliers, extract specific fields from structured data, or create combinations of features for model training. While pandas provides vectorized operations for entire columns, understanding list comprehensions gives you fine-grained control when you need to process individual lists or create custom transformations that do not fit standard operations. Moreover, the mental model of list comprehensions transfers directly to dictionary and set comprehensions, and similar patterns appear in generator expressions that you will use for memory-efficient processing.

This comprehensive guide takes you from your first simple comprehension through confident mastery of this elegant Python feature. You will learn the basic syntax for creating lists through comprehensions, how to filter items using conditional logic within comprehensions, how to transform and combine data in sophisticated ways, and when nested comprehensions help versus when they obscure. You will also discover performance characteristics, common patterns that appear in data science code, and best practices for writing readable comprehensions. By the end, you will recognize opportunities to replace verbose loops with concise comprehensions and write more elegant, Pythonic code.

The Basic List Comprehension Syntax

List comprehensions create new lists by applying an expression to each item in an existing collection. The basic syntax uses square brackets containing an expression followed by a for clause:

# Traditional loop approach

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

squares = []

for num in numbers:

squares.append(num ** 2)

print(squares) # [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

# List comprehension approach

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

squares = [num ** 2 for num in numbers]

print(squares) # [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]The comprehension reads naturally left to right: “create a list of num squared for each num in numbers.” This directness makes comprehensions highly readable once you internalize the syntax.

Breaking down the anatomy:

[expression for item in iterable]

# ↑ ↑ ↑

# | | |

# Transform Loop Source

# to apply var collectionThe expression can be any valid Python expression using the loop variable:

# Simple transformation

names = ["alice", "bob", "charlie"]

uppercase_names = [name.upper() for name in names]

print(uppercase_names) # ['ALICE', 'BOB', 'CHARLIE']

# Calculations

prices = [10.99, 15.50, 8.75]

prices_with_tax = [price * 1.08 for price in prices]

print(prices_with_tax) # [11.8692, 16.74, 9.45]

# Method calls

temperatures_f = [32, 68, 86, 104]

temperatures_c = [(temp - 32) * 5/9 for temp in temperatures_f]

print(temperatures_c) # [0.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0]You can use list comprehensions with any iterable, not just lists:

# From tuple

coordinates = (10, 20, 30)

doubled = [x * 2 for x in coordinates]

print(doubled) # [20, 40, 60]

# From string

word = "Python"

letters = [char.upper() for char in word]

print(letters) # ['P', 'Y', 'T', 'H', 'O', 'N']

# From range

evens = [x * 2 for x in range(5)]

print(evens) # [0, 2, 4, 6, 8]The expression position can include more complex operations:

# Multiple operations

words = ["hello", "world", "python"]

processed = [word.upper().strip() for word in words]

# Function calls

def double_and_add_ten(x):

return x * 2 + 10

numbers = [5, 10, 15]

results = [double_and_add_ten(n) for n in numbers]

print(results) # [20, 30, 40]Adding Filtering with Conditionals

List comprehensions can include conditional filters that determine which items to include in the result. The if clause goes at the end:

# Filter even numbers

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

evens = [n for n in numbers if n % 2 == 0]

print(evens) # [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

# Filter strings by length

words = ["a", "ab", "abc", "abcd", "abcde"]

long_words = [word for word in words if len(word) > 3]

print(long_words) # ['abcd', 'abcde']The syntax now has three parts:

[expression for item in iterable if condition]

# ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑

# | | | |

# Transform Loop Source Filter

# to apply var collection conditionYou can combine transformation and filtering:

# Transform and filter

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

squared_evens = [n ** 2 for n in numbers if n % 2 == 0]

print(squared_evens) # [4, 16, 36]

# Clean and filter text

texts = [" hello ", " ", "world", " python ", ""]

cleaned = [text.strip() for text in texts if text.strip()]

print(cleaned) # ['hello', 'world', 'python']The filter condition can be any boolean expression:

# Multiple conditions with 'and'

numbers = range(1, 21)

filtered = [n for n in numbers if n > 5 and n < 15]

print(filtered) # [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

# Multiple conditions with 'or'

numbers = range(1, 11)

filtered = [n for n in numbers if n < 3 or n > 8]

print(filtered) # [1, 2, 9, 10]

# Using 'in' operator

valid_statuses = ['active', 'pending']

statuses = ['active', 'inactive', 'pending', 'closed']

valid = [s for s in statuses if s in valid_statuses]

print(valid) # ['active', 'pending']Filter on properties of complex objects:

# Filter dictionaries

people = [

{'name': 'Alice', 'age': 30},

{'name': 'Bob', 'age': 17},

{'name': 'Charlie', 'age': 25}

]

adults = [person for person in people if person['age'] >= 18]

print(adults) # [{'name': 'Alice', 'age': 30}, {'name': 'Charlie', 'age': 25}]

# Extract and filter

adult_names = [person['name'] for person in people if person['age'] >= 18]

print(adult_names) # ['Alice', 'Charlie']Conditional Expressions Within Comprehensions

Sometimes you want to transform items differently based on conditions rather than filtering them out. Use conditional expressions (ternary operators) in the expression position:

# Transform based on condition

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

result = ['even' if n % 2 == 0 else 'odd' for n in numbers]

print(result) # ['odd', 'even', 'odd', 'even', 'odd', 'even']The conditional expression syntax differs from the filtering if:

# Conditional expression (ternary operator)

[expr_if_true if condition else expr_if_false for item in iterable]

# Versus filtering if

[expression for item in iterable if condition]Practical examples:

# Categorize values

scores = [85, 92, 78, 65, 95, 58]

grades = ['Pass' if score >= 70 else 'Fail' for score in scores]

print(grades) # ['Pass', 'Pass', 'Pass', 'Fail', 'Pass', 'Fail']

# Handle None values

values = [10, None, 25, None, 15]

cleaned = [v if v is not None else 0 for v in values]

print(cleaned) # [10, 0, 25, 0, 15]

# Cap values at maximum

numbers = [15, 25, 105, 50, 200]

capped = [n if n <= 100 else 100 for n in numbers]

print(capped) # [15, 25, 100, 50, 100]You can combine conditional expressions with filtering:

# Transform some items and filter others

numbers = [-5, 3, -2, 8, -1, 6]

# Square positive numbers, filter out negative

result = [n ** 2 for n in numbers if n > 0]

print(result) # [9, 64, 36]

# Or transform all but handle negative differently

result = [n ** 2 if n > 0 else 0 for n in numbers]

print(result) # [0, 9, 0, 64, 0, 36]Nested List Comprehensions

List comprehensions can nest to work with multi-dimensional data or generate combinations:

# Flatten a 2D list

matrix = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

flattened = [num for row in matrix for num in row]

print(flattened) # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]Reading nested comprehensions requires understanding that later for clauses are nested inside earlier ones:

# Equivalent loop structure

matrix = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]]

flattened = []

for row in matrix: # Outer comprehension clause

for num in row: # Inner comprehension clause

flattened.append(num)Generate combinations:

# Cartesian product

colors = ['red', 'blue']

sizes = ['S', 'M', 'L']

combinations = [(color, size) for color in colors for size in sizes]

print(combinations)

# [('red', 'S'), ('red', 'M'), ('red', 'L'),

# ('blue', 'S'), ('blue', 'M'), ('blue', 'L')]Process nested structures:

# Extract values from nested dictionaries

data = [

{'name': 'Alice', 'scores': [85, 90, 88]},

{'name': 'Bob', 'scores': [78, 82, 80]}

]

all_scores = [score for person in data for score in person['scores']]

print(all_scores) # [85, 90, 88, 78, 82, 80]Create matrices:

# Generate 2D matrix

matrix = [[i * j for j in range(1, 4)] for i in range(1, 4)]

print(matrix)

# [[1, 2, 3],

# [2, 4, 6],

# [3, 6, 9]]However, deeply nested comprehensions can become unreadable. Consider breaking them into multiple steps:

# Hard to read

result = [[x * y for y in range(5) if y % 2 == 0]

for x in range(5) if x % 2 != 0]

# Clearer with intermediate step

odd_numbers = [x for x in range(5) if x % 2 != 0]

result = [[x * y for y in range(5) if y % 2 == 0]

for x in odd_numbers]Dictionary and Set Comprehensions

The comprehension syntax extends to dictionaries and sets with similar patterns:

# Dictionary comprehension

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

squared_dict = {n: n ** 2 for n in numbers}

print(squared_dict) # {1: 1, 2: 4, 3: 9, 4: 16, 5: 25}

# Create dictionary from two lists

names = ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']

ages = [30, 25, 35]

people = {name: age for name, age in zip(names, ages)}

print(people) # {'Alice': 30, 'Bob': 25, 'Charlie': 35}Dictionary comprehensions with filtering:

# Filter dictionary

scores = {'Alice': 85, 'Bob': 92, 'Charlie': 78, 'David': 65}

passing = {name: score for name, score in scores.items() if score >= 70}

print(passing) # {'Alice': 85, 'Bob': 92, 'Charlie': 78}Set comprehensions eliminate duplicates:

# Set comprehension

numbers = [1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4, 4]

unique_squares = {n ** 2 for n in numbers}

print(unique_squares) # {1, 4, 9, 16}

# Extract unique words

text = "the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog"

unique_words = {word for word in text.split()}

print(unique_words) # {'the', 'quick', 'brown', 'fox', 'jumps', 'over', 'lazy', 'dog'}Common Data Science Patterns

List comprehensions excel at data preprocessing and feature engineering tasks:

# Normalize numerical data

values = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

max_value = max(values)

normalized = [v / max_value for v in values]

print(normalized) # [0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0]

# Standardize text for analysis

responses = ["Yes", "YES", "no", "No", "Maybe", "MAYBE"]

standardized = [r.lower() for r in responses]

print(standardized) # ['yes', 'yes', 'no', 'no', 'maybe', 'maybe']

# Extract features from structured data

records = [

"2024-01-15,85,Pass",

"2024-01-16,78,Pass",

"2024-01-17,62,Fail"

]

scores = [int(record.split(',')[1]) for record in records]

print(scores) # [85, 78, 62]Creating categorical features:

# Bin continuous values

ages = [15, 25, 35, 45, 55, 65, 75]

categories = ['young' if age < 30 else 'middle' if age < 60 else 'senior'

for age in ages]

print(categories) # ['young', 'young', 'middle', 'middle', 'middle', 'senior', 'senior']

# One-hot encoding (simplified)

categories = ['cat', 'dog', 'cat', 'bird', 'dog']

is_cat = [1 if c == 'cat' else 0 for c in categories]

print(is_cat) # [1, 0, 1, 0, 0]Cleaning and validating data:

# Remove invalid entries

ages = [25, -5, 30, 150, 22, 0, 45]

valid_ages = [age for age in ages if 0 < age < 120]

print(valid_ages) # [25, 30, 22, 45]

# Clean and validate emails

emails = ["user@example.com", "invalid", "test@gmail.com", "@test.com"]

valid_emails = [email for email in emails if '@' in email and email.count('@') == 1]

print(valid_emails) # ['user@example.com', 'test@gmail.com']Performance Considerations

List comprehensions generally execute faster than equivalent loops because they are optimized at the C level in CPython:

import time

# Loop approach

start = time.time()

squares = []

for i in range(1000000):

squares.append(i ** 2)

loop_time = time.time() - start

# Comprehension approach

start = time.time()

squares = [i ** 2 for i in range(1000000)]

comp_time = time.time() - start

print(f"Loop: {loop_time:.4f}s")

print(f"Comprehension: {comp_time:.4f}s")

# Comprehension is typically 20-30% fasterHowever, readability sometimes matters more than minor performance gains:

# Fast but hard to read

result = [x for x in [y ** 2 for y in range(100)] if x % 10 == 0]

# Slower but clearer

squares = [y ** 2 for y in range(100)]

result = [x for x in squares if x % 10 == 0]For very large datasets, consider generator expressions that produce items on-demand rather than creating entire lists in memory:

# List comprehension - creates entire list in memory

squares = [x ** 2 for x in range(1000000)]

# Generator expression - produces items on demand

squares = (x ** 2 for x in range(1000000))When to Use Comprehensions vs. Loops

List comprehensions excel for straightforward transformations and filtering, but traditional loops remain better for complex logic:

# Good for comprehensions - simple and clear

doubled = [x * 2 for x in numbers]

adults = [p for p in people if p['age'] >= 18]

# Better as loops - complex logic

results = []

for item in items:

if complex_condition(item):

processed = process(item)

if validate(processed):

results.append(transform(processed))

else:

results.append(default_value)Use loops when:

- Logic involves multiple statements per item

- You need to handle exceptions for individual items

- The code is more readable as explicit loops

- You need to break or continue based on conditions

Use comprehensions when:

- Transformation is simple and clear

- Filtering logic is straightforward

- The entire operation fits readably on one or a few lines

Best Practices

Follow these guidelines for effective comprehensions:

Keep comprehensions short and readable:

# Too complex

result = [transform(x) if condition1(x) else alternative(x)

for x in items if prefilter(x) and validate(x)]

# Better - break into steps

filtered = [x for x in items if prefilter(x) and validate(x)]

result = [transform(x) if condition1(x) else alternative(x)

for x in filtered]Use meaningful variable names:

# Unclear

result = [x.upper() for x in xs]

# Clear

uppercase_names = [name.upper() for name in names]Avoid side effects in comprehensions:

# Bad - don't do this

[results.append(x * 2) for x in numbers] # Creates unnecessary list

# Good - use loop for side effects

for number in numbers:

results.append(number * 2)Consider readability over cleverness:

# Clever but confusing

result = [x if x > 0 else 0 if x > -5 else -5 for x in values]

# Clearer with explicit function

def clip(value, minimum=-5, maximum=None):

if maximum and value > maximum:

return maximum

if value < minimum:

return minimum

return value

result = [clip(x) for x in values]Conclusion

List comprehensions represent elegant, Pythonic code that transforms verbose loops into concise expressions. They make your intent clear, reduce boilerplate, and often execute faster than equivalent loops. For data scientists, comprehensions become essential tools for preprocessing data, creating features, filtering observations, and transforming values. The syntax transfers to dictionary and set comprehensions, providing consistent patterns across different collection types.

Mastering list comprehensions requires practice recognizing when they improve code versus when explicit loops communicate better. Simple transformations and filtering operations benefit greatly from comprehensions. Complex logic with multiple steps per item often reads more clearly as explicit loops. Developing judgment about this tradeoff comes with experience, but the guideline remains: if you can express the operation clearly in a comprehension that fits on one to three lines, use a comprehension; otherwise, use a loop.

As you continue in data science, you will encounter comprehensions throughout Python code and libraries. Pandas operations often return results you process with comprehensions. Data preprocessing pipelines use comprehensions extensively. Understanding this syntax deeply enables you to read others’ code fluently and write your own code elegantly. Practice converting loops to comprehensions when appropriate, and soon the pattern will feel natural, letting you focus on the data transformations themselves rather than iteration mechanics.