Introduction

After learning to store data in collections like lists and dictionaries and to organize code into reusable functions, you face a fundamental challenge: how do you perform the same operation on every item in a collection without writing the same code hundreds or thousands of times? If you have a list of temperatures and want to convert each one from Fahrenheit to Celsius, you could access each item individually and perform the calculation, but this approach becomes impossible with large datasets. Loops solve this problem by letting you repeat blocks of code automatically, processing each item in a collection or continuing until some condition is met.

Loops represent one of the most powerful concepts in programming, transforming tedious repetitive tasks into single lines of code that process any amount of data. Think about common data science operations: calculating the mean requires adding every number in a dataset, cleaning text requires processing every string in a column, and training machine learning models involves iterating through data points repeatedly. All these operations fundamentally rely on loops. Understanding loops deeply separates those who can only work with tiny toy datasets from those who confidently process real-world data of any size.

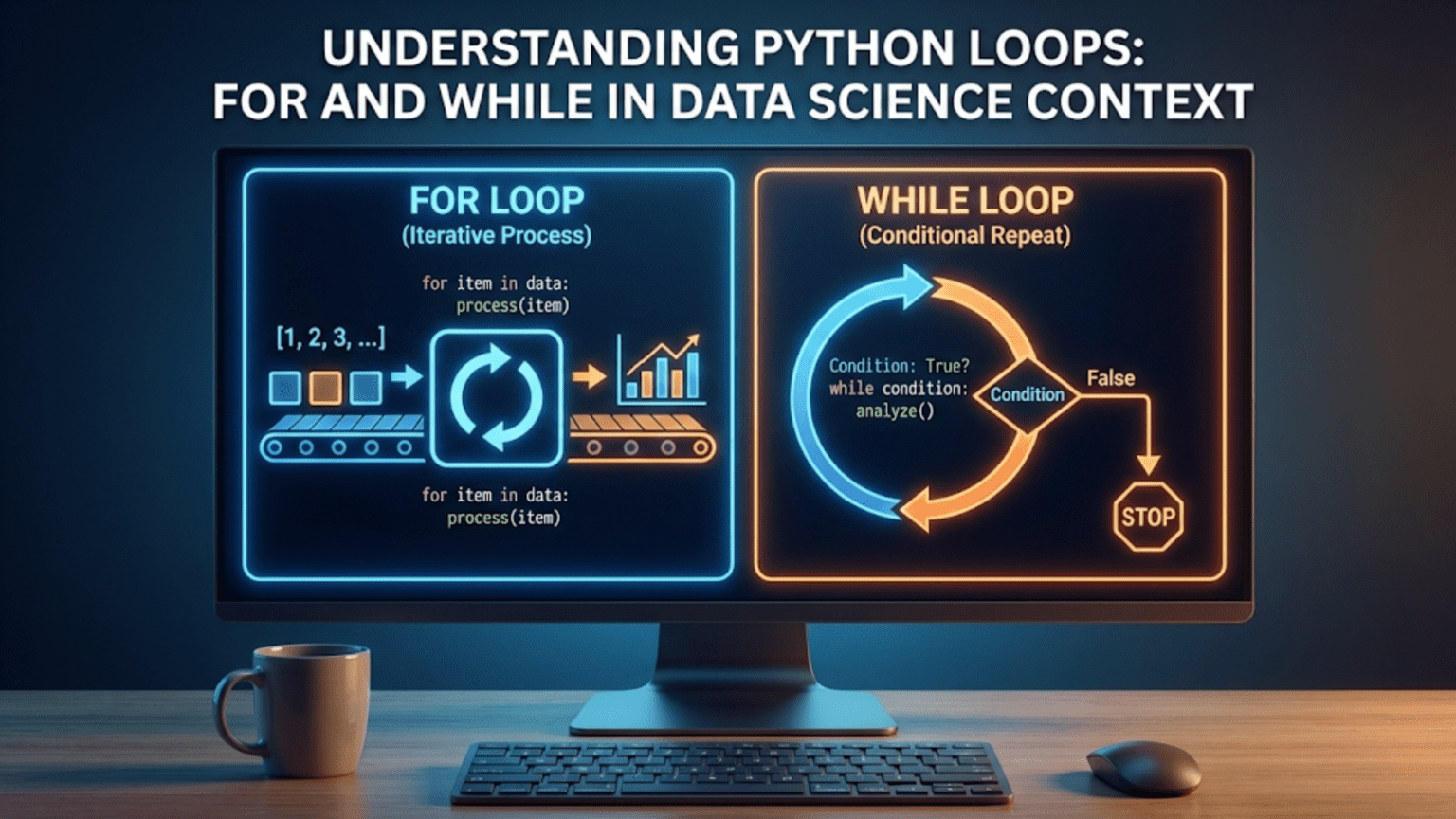

Python provides two main types of loops, each suited for different situations. For loops excel at iterating through collections when you know what items you want to process. While loops continue executing as long as some condition remains true, making them perfect for situations where you do not know in advance how many iterations you need. Both loop types appear constantly in data science code, from the simple task of summing values to the complex job of iteratively training neural networks until they converge. Mastering both types gives you complete control over repetitive operations.

This comprehensive guide takes you from your first loop through confident mastery of iteration in Python. You will learn how for loops iterate through lists, dictionaries, and other collections, how while loops continue until conditions are met, how to control loop execution with break and continue statements, and common patterns that appear repeatedly in data science code. You will also discover best practices for writing efficient loops and when to use comprehensions or vectorized operations instead. By the end, loops will feel natural and you will recognize opportunities to use them throughout your data analysis work.

The For Loop: Iterating Through Collections

For loops let you execute a block of code once for each item in a collection. This pattern appears constantly in data science when you need to process every element in a list, every key in a dictionary, or every character in a string. The basic syntax uses the for keyword, a variable name to hold each item, the in keyword, the collection to iterate through, and a colon followed by indented code:

temperatures = [72, 75, 78, 82, 85]

for temp in temperatures:

print(f"Temperature: {temp}°F")This loop runs five times, once for each temperature in the list. Each iteration, Python assigns the next value to the variable temp, then executes the indented code. The variable temp exists only inside the loop and automatically gets updated with each item.

You can name the loop variable anything you want, though descriptive names make code more readable:

# Generic but acceptable

for item in temperatures:

print(item)

# More descriptive

for temperature in temperatures:

print(temperature)

# Common single-letter convention for simple loops

for t in temperatures:

print(t)The indented block can contain multiple statements:

prices = [10.99, 15.50, 8.75, 22.00]

for price in prices:

tax = price * 0.08

total = price + tax

print(f"Price: ${price:.2f}, Tax: ${tax:.2f}, Total: ${total:.2f}")For loops work with any iterable object, including lists, tuples, strings, and dictionaries:

# Iterating through a string

word = "Python"

for letter in word:

print(letter) # P, y, t, h, o, n (one per line)

# Iterating through a tuple

coordinates = (10, 20, 30)

for value in coordinates:

print(value)When iterating through dictionaries, the default behavior loops through keys:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

for key in person:

print(key) # Prints: name, age, cityTo access both keys and values, use the items() method:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

for key, value in person.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}")This pattern uses tuple unpacking where each iteration provides both the key and value, which you capture in two variables.

You can iterate through just the values using values():

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

for value in person.values():

print(value) # Prints: Alice, 30, BostonThe Range Function: Generating Number Sequences

The range() function generates sequences of numbers, which proves extremely useful with for loops. It creates an iterable that produces numbers on demand rather than creating a list in memory:

# Numbers from 0 to 4

for i in range(5):

print(i) # 0, 1, 2, 3, 4Notice that range(5) produces five numbers starting at zero and stopping before five. This zero-based counting with exclusive end matches Python’s indexing conventions.

Range accepts start, stop, and step parameters:

# Start at 1, stop before 6

for i in range(1, 6):

print(i) # 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

# Start at 0, stop before 10, step by 2

for i in range(0, 10, 2):

print(i) # 0, 2, 4, 6, 8

# Count backwards

for i in range(10, 0, -1):

print(i) # 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1Range commonly appears when you need to repeat an action a specific number of times:

# Repeat an action 10 times

for i in range(10):

print("Processing...")Or when you need both the index and the value from a list:

names = ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"]

for i in range(len(names)):

print(f"Index {i}: {names[i]}")However, Python provides a more elegant approach for this pattern using enumerate():

names = ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"]

for index, name in enumerate(names):

print(f"Index {index}: {name}")Enumerate returns pairs of index and value, which you can unpack into two variables. This pattern appears frequently when you need both position and value during iteration.

Common For Loop Patterns in Data Science

Several patterns appear repeatedly in data science code. Recognizing these patterns helps you write effective loops quickly.

Accumulating values builds a total by adding each item:

numbers = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

total = 0

for number in numbers:

total += number

print(f"Total: {total}") # 150While Python’s built-in sum() function handles this specific case, the pattern generalizes to many accumulation tasks:

# Count items meeting a condition

ages = [25, 17, 30, 15, 22, 19, 35]

adults = 0

for age in ages:

if age >= 18:

adults += 1

print(f"Adults: {adults}")Building new lists by transforming each element:

fahrenheit = [32, 68, 86, 104]

celsius = []

for temp_f in fahrenheit:

temp_c = (temp_f - 32) * 5/9

celsius.append(temp_c)

print(celsius) # [0.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0]Note that list comprehensions provide more concise syntax for this pattern, which you will learn in a future article.

Processing parallel lists using zip():

names = ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"]

scores = [85, 92, 78]

for name, score in zip(names, scores):

print(f"{name}: {score}")Zip combines multiple iterables, stopping when the shortest one is exhausted.

Filtering lists based on conditions:

numbers = [12, 7, 19, 4, 22, 15, 8]

large_numbers = []

for num in numbers:

if num > 10:

large_numbers.append(num)

print(large_numbers) # [12, 19, 22, 15]Finding maximum or minimum values with tracking:

scores = [85, 92, 78, 95, 88]

max_score = scores[0]

for score in scores:

if score > max_score:

max_score = score

print(f"Maximum score: {max_score}")Again, Python’s max() function handles this specific case, but the pattern applies to finding items with maximum custom properties.

Nested Loops: Iterating Through Multiple Dimensions

Sometimes you need to iterate through nested collections like lists of lists or process combinations of items. Nested loops handle these situations by placing one loop inside another:

matrix = [

[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9]

]

for row in matrix:

for value in row:

print(value, end=' ')

print() # New line after each rowThis prints each row of the matrix. The outer loop iterates through rows, and the inner loop iterates through values within each row.

Nested loops let you generate combinations:

sizes = ["Small", "Medium", "Large"]

colors = ["Red", "Blue", "Green"]

for size in sizes:

for color in colors:

print(f"{size} {color}")

# Generates all 9 combinationsProcessing two-dimensional data appears frequently in data science:

# Temperature readings from multiple cities over multiple days

city_temperatures = [

[72, 75, 78], # City 1

[65, 68, 70], # City 2

[80, 82, 85] # City 3

]

for city_index, temperatures in enumerate(city_temperatures):

avg_temp = sum(temperatures) / len(temperatures)

print(f"City {city_index + 1} average: {avg_temp:.1f}°F")Be cautious with nested loops as they can become slow with large datasets. A loop inside a loop means the inner code runs outer_length times inner_length times, which grows quickly.

The While Loop: Continuing Until a Condition Changes

While loops repeat code as long as a condition remains true, making them suitable for situations where you do not know in advance how many iterations you need. The syntax uses the while keyword, a condition, a colon, and indented code:

count = 0

while count < 5:

print(f"Count: {count}")

count += 1This loop continues while count is less than 5, printing the count and incrementing it each iteration. Eventually count reaches 5, the condition becomes false, and the loop exits.

While loops require careful management to avoid infinite loops where the condition never becomes false:

# Dangerous - infinite loop!

count = 0

while count < 5:

print(count)

# Forgot to increment count - loop never ends!Always ensure that something inside the loop eventually makes the condition false.

While loops work well for iterative processes in data science:

# Simple convergence example

value = 100

tolerance = 1.0

while value > tolerance:

value = value * 0.9

print(f"Current value: {value:.2f}")

print(f"Converged to {value:.2f}")This pattern appears in optimization algorithms that iterate until convergence.

Another common pattern involves continuing until finding what you are looking for:

numbers = [5, 12, 8, 23, 15, 7, 19]

target = 15

index = 0

while index < len(numbers):

if numbers[index] == target:

print(f"Found {target} at index {index}")

break

index += 1For loops generally provide cleaner code for this pattern, but while loops work when you need more control over iteration.

While loops suit iterative numerical methods:

# Newton's method example (simplified)

guess = 10

target = 25

tolerance = 0.01

while abs(guess * guess - target) > tolerance:

guess = (guess + target / guess) / 2

print(f"Current guess: {guess:.4f}")

print(f"Square root of {target} is approximately {guess:.4f}")Controlling Loop Execution: Break and Continue

Python provides keywords to modify how loops execute. The break statement immediately exits the loop, while continue skips the rest of the current iteration and moves to the next one.

Break exits the loop entirely when you find what you need:

numbers = [1, 5, 12, 8, 15, 22, 7]

for num in numbers:

if num > 20:

print(f"Found number greater than 20: {num}")

break

print(f"Checking {num}")This stops as soon as it finds a number greater than 20, not checking the remaining numbers.

Continue skips to the next iteration:

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

for num in numbers:

if num % 2 == 0:

continue # Skip even numbers

print(num) # Only prints odd numbersBoth keywords work in while loops too:

count = 0

while count < 10:

count += 1

if count % 2 == 0:

continue # Skip even numbers

if count > 7:

break # Stop when greater than 7

print(count) # Prints: 1, 3, 5, 7Use these keywords judiciously. Overuse makes code hard to follow. Often you can restructure logic to avoid them:

# With continue

for num in numbers:

if num % 2 == 0:

continue

print(num)

# Without continue - equally clear

for num in numbers:

if num % 2 != 0:

print(num)Loop Best Practices and Common Mistakes

Writing effective loops requires understanding common pitfalls and following established patterns.

Avoid modifying lists while iterating through them:

# Dangerous - don't do this

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

for num in numbers:

if num % 2 == 0:

numbers.remove(num) # Modifying while iterating!

# This produces unexpected results

# Safe approach - create new list

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

odd_numbers = [num for num in numbers if num % 2 != 0]Preallocate lists when building large collections:

# Less efficient - list grows repeatedly

result = []

for i in range(10000):

result.append(i * 2)

# More efficient for known size

result = [0] * 10000

for i in range(10000):

result[i] = i * 2

# Best - use list comprehension

result = [i * 2 for i in range(10000)]Minimize work inside loops:

# Inefficient - recalculates len() every iteration

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

for i in range(len(numbers)):

print(numbers[i])

# Better - len() called once

length = len(numbers)

for i in range(length):

print(numbers[i])

# Best - iterate directly

for num in numbers:

print(num)Use meaningful variable names even in loops:

# Unclear

for x in data:

y = x * 2

z.append(y)

# Clear

for value in data:

doubled = value * 2

results.append(doubled)Check for empty collections before looping when it matters:

numbers = []

# This works but runs zero iterations

for num in numbers:

print(num)

# Better when you need to handle empty case differently

if numbers:

for num in numbers:

print(num)

else:

print("No data to process")When to Use Loops vs. Alternatives

While loops are powerful, Python often provides more efficient or readable alternatives for common patterns.

Use built-in functions when available:

# With loop

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

total = 0

for num in numbers:

total += num

# Better - use built-in

total = sum(numbers)Use list comprehensions for transformations:

# With loop

squares = []

for num in range(10):

squares.append(num ** 2)

# Better - list comprehension

squares = [num ** 2 for num in range(10)]Use any() and all() for boolean checks:

# With loop

numbers = [2, 4, 6, 8]

all_even = True

for num in numbers:

if num % 2 != 0:

all_even = False

break

# Better - use all()

all_even = all(num % 2 == 0 for num in numbers)For data science work, vectorized operations with NumPy or pandas often replace explicit loops:

# With loop

import time

numbers = list(range(1000000))

squared = []

start = time.time()

for num in numbers:

squared.append(num ** 2)

print(f"Loop: {time.time() - start:.4f} seconds")

# With NumPy - much faster

import numpy as np

numbers = np.arange(1000000)

start = time.time()

squared = numbers ** 2

print(f"NumPy: {time.time() - start:.4f} seconds")The vectorized version runs orders of magnitude faster for large datasets.

However, loops remain valuable when logic does not fit vectorized operations, when clarity matters more than small performance differences, or when working with complex nested structures.

Practical Data Science Examples

Let us explore loops in realistic data science contexts.

Cleaning survey data:

survey_responses = ["yes", "YES ", " no", " Yes", "NO", "maybe "]

cleaned_responses = []

for response in survey_responses:

# Clean each response

cleaned = response.strip().lower()

cleaned_responses.append(cleaned)

print(cleaned_responses) # ['yes', 'yes', 'no', 'yes', 'no', 'maybe']

# Count responses

counts = {}

for response in cleaned_responses:

if response in counts:

counts[response] += 1

else:

counts[response] = 1

print(counts) # {'yes': 3, 'no': 2, 'maybe': 1}Processing multiple data files:

file_names = ["data_2020.csv", "data_2021.csv", "data_2022.csv"]

all_records = []

for file_name in file_names:

print(f"Processing {file_name}...")

# In real code, you would read the file here

# For this example, simulating with a list

records = [file_name] * 3 # Placeholder

all_records.extend(records)

print(f"Total records: {len(all_records)}")Iterative calculation with convergence:

# Simple gradient descent example

learning_rate = 0.1

value = 10.0

target = 2.0

max_iterations = 100

for iteration in range(max_iterations):

error = value - target

value = value - learning_rate * error

if abs(error) < 0.01:

print(f"Converged after {iteration + 1} iterations")

break

if iteration % 10 == 0:

print(f"Iteration {iteration}: value = {value:.4f}, error = {error:.4f}")

print(f"Final value: {value:.4f}")Binning continuous data:

ages = [15, 22, 34, 45, 67, 23, 19, 52, 71, 28]

bins = [0, 18, 35, 55, 100]

bin_labels = ["child", "young_adult", "middle_aged", "senior"]

categorized = []

for age in ages:

for i in range(len(bins) - 1):

if bins[i] <= age < bins[i + 1]:

categorized.append(bin_labels[i])

break

print("Ages:", ages)

print("Categories:", categorized)Conclusion

Loops represent fundamental building blocks for processing data in Python. For loops let you iterate through collections, processing each item systematically. While loops continue until conditions are met, handling situations where you do not know in advance how many iterations you need. Together, these loop types give you complete control over repetitive operations that appear constantly in data science work.

Understanding loops deeply separates beginners who struggle with any dataset larger than they can process manually from practitioners who confidently handle data of any size. Every time you calculate statistics across observations, apply transformations to features, clean text data, or train models iteratively, you rely on loops either explicitly or through higher-level abstractions that use loops internally.

As you progress in data science, you will learn more sophisticated iteration techniques including list comprehensions, generator expressions, and vectorized operations with NumPy and pandas. However, these advanced techniques build directly on the loop fundamentals you have learned here. The patterns of accumulation, transformation, filtering, and convergence that you practice with loops transfer directly to these more advanced tools.

Practice writing loops for common operations: summing values, finding maximums, transforming data, and filtering collections. Build intuition about when to use for versus while, when to break or continue, and when alternatives like built-in functions or comprehensions provide cleaner solutions. The muscle memory you develop now makes loops feel natural when you encounter them in real data science projects. Master loops, and you unlock the ability to process data systematically and efficiently, a skill that remains valuable throughout your entire data science career.