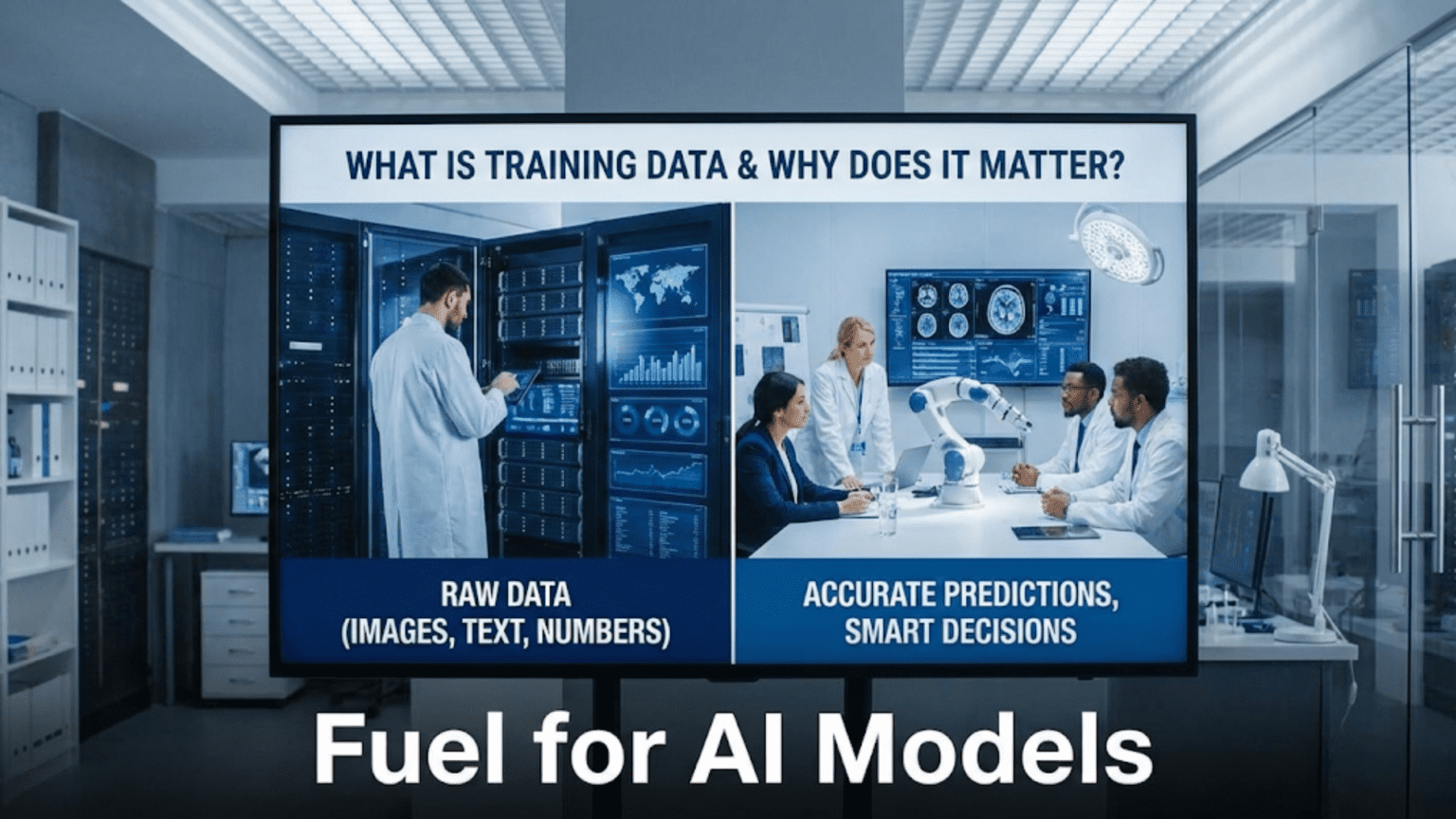

You’ve probably heard that artificial intelligence and machine learning are “data-driven” technologies. Perhaps you’ve read that AI systems “learn from data” or that “data is the new oil” in the AI economy. But what does this actually mean? What is this data that’s supposedly so valuable, and why do AI systems need it?

The answer centers on a concept called training data—the examples that machine learning algorithms learn from. Training data is quite literally what teaches AI systems to perform their tasks. Without appropriate training data, even the most sophisticated machine learning algorithm is useless. With high-quality training data, even relatively simple algorithms can achieve impressive results.

Understanding training data is fundamental to understanding modern AI. It shapes what AI systems can do, determines their performance, influences their biases, and constrains their applications. Whether you’re planning to work with AI, make decisions about AI systems, or simply want to understand how AI works, you need to understand training data.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore what training data is, why it matters so much, what makes training data good or bad, how it’s collected and prepared, and what challenges and considerations surround its use. By the end, you’ll understand one of the most critical—yet often overlooked—aspects of artificial intelligence.

What Exactly Is Training Data?

At its most basic, training data is the set of examples that a machine learning algorithm learns from. It’s the information used to teach an AI system to perform a specific task.

A Simple Analogy

Think about how you learned to recognize different types of fruit as a child. Your parents or teachers showed you many examples:

- “This red, round fruit with a stem is an apple”

- “This yellow, curved fruit is a banana”

- “This small, round, purple fruit in bunches is a grape”

After seeing enough examples, you learned to recognize these fruits on your own, even varieties you’d never seen before. You learned the patterns that distinguish apples from bananas from grapes.

Training data works the same way for AI. When building a fruit recognition system, you provide the algorithm with many labeled images:

- Image of Red Delicious apple → Label: “apple”

- Image of Granny Smith apple → Label: “apple”

- Image of Cavendish banana → Label: “banana”

- Image of plantain → Label: “banana”

- Image of red grapes → Label: “grape”

- Image of green grapes → Label: “grape”

The algorithm examines these examples, identifies patterns that distinguish different fruits, and learns to classify new images it hasn’t seen before.

Formal Definition

More formally, training data is a dataset consisting of input examples (also called features or attributes) and corresponding output values (also called labels or targets in supervised learning). The machine learning algorithm analyzes this data to learn the relationship between inputs and outputs, creating a model that can make predictions on new, unseen data.

Components of Training Data

Training data typically includes:

Input Features: The information provided to the algorithm

- For image recognition: pixel values

- For spam detection: email text, sender, subject

- For house price prediction: square footage, bedrooms, location

- For speech recognition: audio waveforms

Output Labels (for supervised learning): The correct answer for each example

- For image recognition: “cat”, “dog”, “car”

- For spam detection: “spam” or “not spam”

- For house price prediction: actual sale price

- For speech recognition: the words spoken

Metadata: Additional information about the data

- When it was collected

- How it was collected

- What preprocessing was applied

- Quality ratings or confidence scores

Why Training Data Matters So Much

Training data isn’t just important for AI—it’s absolutely fundamental. Here’s why it matters more than you might think.

Training Data Determines What AI Can Learn

An AI system can only learn patterns present in its training data. If you train a dog-recognition system exclusively on images of golden retrievers and German shepherds, it will struggle with poodles and pugs. The system doesn’t have a magical ability to generalize beyond its training examples—it learns what it’s shown.

This has profound implications:

Limited training data = Limited capabilities: Systems trained on narrow datasets can’t handle situations outside their training distribution. A medical diagnosis system trained only on data from one hospital might perform poorly when deployed at a different hospital with different equipment or patient demographics.

Diverse training data = Broader capabilities: Systems trained on diverse, representative data generalize better to real-world variety. An image recognition system trained on photos from different countries, seasons, lighting conditions, and camera angles will be more robust than one trained on homogeneous data.

Training Data Determines Performance

The quantity and quality of training data directly impact AI system performance. This relationship is so strong that researchers often find that more and better data improves results more than algorithmic innovations.

Data quantity matters: With few training examples, algorithms struggle to learn robust patterns. With many examples, they can learn more subtle and reliable patterns. Studies have shown that increasing training data often improves performance more than switching to more sophisticated algorithms.

Data quality matters even more: High-quality training data with accurate labels, representative samples, and relevant features produces better models than low-quality data, regardless of quantity. Garbage in, garbage out applies forcefully to machine learning.

Training Data Embeds Biases

Training data doesn’t just teach AI what to do—it also teaches biases, stereotypes, and historical patterns present in the data. If training data reflects societal biases, the resulting AI system will likely perpetuate or even amplify those biases.

Historical hiring data: Train an AI on historical hiring decisions, and it may learn that certain groups were historically hired less frequently—not because they were less qualified, but due to discrimination. The AI then perpetuates this discrimination.

Facial recognition: Systems trained primarily on images of light-skinned individuals perform worse on dark-skinned faces, not because of algorithmic limitations but because of imbalanced training data.

Language models: AI trained on internet text learns stereotypes and biases present in that text, associating certain professions with certain genders or making assumptions based on names or cultural references.

This means training data isn’t neutral—it encodes the patterns, including the problematic ones, of its source.

Training Data Represents Real-World Complexity

AI systems face the real world in all its messy, complicated, ambiguous glory. Training data must somehow capture this complexity. The gap between training data and real-world conditions often explains AI failures.

Controlled vs. Uncontrolled Conditions: Training data collected in controlled conditions may not represent the chaos of real-world deployment. A self-driving car trained on data from perfect weather conditions will struggle in heavy rain or snow.

Edge Cases: Rare but important situations might not appear in training data. A content moderation system might not have seen examples of new types of harmful content, rendering it ineffective against novel threats.

Changing Patterns: The world changes, but training data represents a specific time period. A financial prediction model trained on pre-pandemic data may perform poorly in post-pandemic markets with different dynamics.

Types of Training Data

Training data comes in various forms depending on the learning approach and the problem being solved.

Supervised Learning Data

In supervised learning, training data includes both inputs and correct outputs. The algorithm learns to map inputs to outputs based on these labeled examples.

Classification Data:

- Input: Image of an animal

- Output: “cat”, “dog”, “bird”, etc.

- Input: Email text and metadata

- Output: “spam” or “not spam”

- Input: Medical scan

- Output: “healthy” or “disease present”

Regression Data:

- Input: House characteristics (size, location, age)

- Output: Sale price (numerical value)

- Input: Historical stock data

- Output: Future price (numerical value)

Creating supervised training data requires labeling—humans (or sometimes other algorithms) must provide the correct output for each input example. This labeling process can be time-consuming and expensive but produces the richest learning signal.

Unsupervised Learning Data

In unsupervised learning, training data includes only inputs without explicit labels. The algorithm discovers structure and patterns without being told what to look for.

Clustering Data:

- Input: Customer purchase histories

- Output: Algorithm discovers natural customer segments

- Input: Document collection

- Output: Algorithm discovers topic groupings

Dimensionality Reduction Data:

- Input: High-dimensional data (many features)

- Output: Algorithm finds lower-dimensional representation preserving important information

Unsupervised learning data is easier to obtain (no labeling required) but provides a weaker learning signal. The algorithm must discover meaningful patterns without guidance about what patterns matter.

Semi-Supervised Learning Data

Semi-supervised learning uses training data that’s partially labeled—a large amount of unlabeled data and a smaller amount of labeled data.

Example:

- 10,000 unlabeled images

- 100 labeled images

- Algorithm uses labeled examples for guidance while learning from the broader patterns in unlabeled data

This approach is valuable when labeling is expensive but unlabeled data is abundant—a common situation in practice.

Reinforcement Learning Data

Reinforcement learning uses a different type of training data—experiences of trying actions and receiving rewards.

Training Data Structure:

- State: Current situation

- Action: What the agent did

- Reward: Immediate payoff received

- Next State: Resulting situation

Example (Game Playing):

- State: Current game board position

- Action: Move made

- Reward: Win (+1), loss (-1), or neutral (0)

- Next State: Board after move

The algorithm learns which actions lead to better rewards over time. Training data accumulates through interaction with the environment rather than being collected beforehand.

What Makes Training Data Good or Bad?

Not all training data is created equal. Several factors determine training data quality.

Relevance

Training data must be relevant to the task and representative of real-world conditions.

Good: Training a spam detector on actual emails from the target environment Bad: Training on synthetic examples that don’t reflect real spam characteristics

Good: Training a medical AI on diverse patient data from multiple hospitals Bad: Training only on data from one hospital’s specific patient population

Accuracy

Labels and annotations must be correct. Errors in training data lead to errors in learned models.

Common Accuracy Problems:

- Human labelers making mistakes

- Subjective or ambiguous cases labeled inconsistently

- Automated labeling systems introducing errors

- Outdated labels not reflecting current ground truth

Even small percentages of label errors can significantly degrade model performance, especially for difficult edge cases where the model most needs good examples.

Quantity

More training data generally enables learning more complex patterns and achieving better performance, though with diminishing returns.

Rules of Thumb:

- Simple tasks: Hundreds to thousands of examples might suffice

- Moderate complexity: Thousands to tens of thousands

- Complex tasks (image recognition, language understanding): Millions of examples

- Very complex tasks (large language models): Billions of examples

The exact quantity needed depends on task complexity, input dimensionality, algorithm choice, and acceptable performance thresholds.

Balance

For classification tasks, training data should represent all classes appropriately. Imbalanced data can cause models to ignore minority classes.

Imbalanced Example:

- 9,900 “not fraud” examples

- 100 “fraud” examples

A model might achieve 99% accuracy by always predicting “not fraud”—technically high accuracy but completely useless for detecting fraud.

Solutions:

- Collect more minority class examples

- Use sampling techniques to balance classes

- Use algorithms designed for imbalanced data

- Use appropriate evaluation metrics (not just accuracy)

Diversity

Training data should cover the full range of real-world variation the model will encounter.

Dimensions of Diversity:

- Visual: Different lighting, angles, backgrounds, qualities

- Temporal: Different seasons, times of day, trends

- Demographic: Different populations, cultures, languages

- Contextual: Different use scenarios, environments, conditions

Lack of diversity means models fail when encountering variations absent from training data.

Representativeness

Training data should reflect the actual distribution of real-world cases, not just include examples of everything.

Non-Representative Example: If 90% of real medical scans show healthy tissue, but training data is 50% healthy and 50% diseased, the model learns incorrect base rates and will over-predict disease.

Representativeness ensures models make appropriate predictions matching real-world frequencies.

How Training Data Is Collected

Creating training datasets involves various collection methods, each with advantages and trade-offs.

Manual Collection

Human experts or workers collect and label data manually.

Process:

- Define what data is needed

- Collect raw data (photos, text, measurements)

- Have humans provide labels or annotations

- Review for quality

- Compile into training dataset

Advantages:

- High control over quality

- Can ensure diversity and balance

- Can collect exactly what’s needed

Disadvantages:

- Time-consuming and expensive

- Doesn’t scale well to very large datasets

- Subject to human labeler biases and errors

When Used:

- Specialized domains requiring expert knowledge

- Safety-critical applications requiring high quality

- Initial dataset creation for new tasks

Crowdsourcing

Distribute labeling tasks to large numbers of online workers through platforms like Amazon Mechanical Turk, Labelbox, or Scale AI.

Process:

- Break labeling task into simple units

- Distribute to many workers

- Collect multiple labels per example

- Aggregate labels (majority vote)

- Quality control checks

Advantages:

- Scales to large datasets

- Relatively inexpensive

- Can be fast with enough workers

Disadvantages:

- Quality can be variable

- Workers may not have domain expertise

- Difficult for subjective or complex tasks

- Privacy concerns with sensitive data

When Used:

- Large-scale labeling of simple tasks

- Image classification with clear categories

- Bounding box drawing for object detection

- Transcription tasks

Automated Data Collection

Systems automatically collect data from real-world operations.

Examples:

- Web scraping: Collecting text, images, or structured data from websites

- Sensors: IoT devices, vehicles, equipment generating operational data

- Logs: User interactions, system events, transactions

- Synthetic generation: Creating artificial data through simulation

Advantages:

- Can generate massive datasets

- Inexpensive per example

- Continuous collection possible

Disadvantages:

- May lack labels (requires separate labeling)

- Quality can be inconsistent

- May include noise, errors, or irrelevant data

- Ethical and legal considerations (especially web scraping)

When Used:

- Internet-scale datasets

- Continuous learning systems

- Simulation environments

- Data augmentation

Transfer and Pre-existing Datasets

Use publicly available datasets or transfer data from related tasks.

Public Datasets:

- ImageNet: 14 million labeled images

- COCO: Object detection dataset

- Common Crawl: Web-scale text data

- UCI Machine Learning Repository: Various datasets

Advantages:

- Immediate availability

- Often high quality

- Standardized for benchmarking

- No collection cost

Disadvantages:

- May not match specific needs

- Could include biases or limitations

- Privacy or licensing considerations

- Everyone uses same data (less competitive advantage)

When Used:

- Research and education

- Benchmarking algorithms

- Transfer learning base

- Prototyping before custom collection

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

Raw training data rarely goes directly into machine learning algorithms. It requires preparation and preprocessing.

Data Cleaning

Remove or correct errors, inconsistencies, and irrelevant information.

Common Cleaning Tasks:

- Removing duplicates: Identical examples provide no additional information

- Handling missing values: Decide whether to remove, impute, or flag missing data

- Fixing errors: Correct obvious mistakes in data or labels

- Removing outliers: Extremely unusual values might be errors or irrelevant

Data Transformation

Convert data into formats suitable for machine learning algorithms.

Common Transformations:

- Normalization/Scaling: Adjust features to similar ranges (e.g., 0-1 or standardized)

- Encoding: Convert categorical variables to numerical representations

- Feature extraction: Create useful features from raw data (e.g., extracting date components)

- Dimensionality reduction: Reduce number of features while preserving information

Data Augmentation

Create additional training examples by applying transformations to existing data.

For Images:

- Rotate, flip, crop

- Adjust brightness, contrast, saturation

- Add noise

- Apply filters

For Text:

- Synonym replacement

- Sentence reordering

- Back-translation (translate to another language and back)

For Audio:

- Time stretching

- Pitch shifting

- Adding background noise

Benefits:

- Increases effective dataset size

- Improves model robustness

- Reduces overfitting

- Makes models invariant to irrelevant variations

Caution:

- Augmentations should preserve labels (don’t flip images with directional text)

- Should reflect real-world variations

- Excessive augmentation can introduce unrealistic examples

Feature Engineering

Create new features from existing data to help algorithms learn better.

Examples:

- From timestamps: Extract hour, day of week, season

- From text: Count words, calculate sentiment, identify entities

- From multiple features: Create interaction terms, ratios, differences

Good feature engineering can dramatically improve model performance, though deep learning has reduced its necessity by learning features automatically.

Training, Validation, and Test Data: The Split

Training data doesn’t all serve the same purpose. It’s typically split into three subsets.

Training Set (Typically 60-80% of Data)

Actually used to train the model—the algorithm adjusts parameters based on this data.

Purpose: Teach the model patterns in the data

Validation Set (Typically 10-20% of Data)

Used during model development to:

- Tune hyperparameters

- Select between different model architectures

- Decide when to stop training (early stopping)

- Prevent overfitting

Purpose: Guide model development without contaminating test evaluation

The model never learns directly from validation data, but validation results influence development decisions.

Test Set (Typically 10-20% of Data)

Set aside completely until final evaluation. Never used during development.

Purpose: Provide unbiased estimate of model performance on new data

The test set simulates real-world data the model has never seen. Using it only once for final evaluation ensures the performance estimate isn’t optimistically biased by development decisions.

Why This Split Matters

Without proper splitting, you can’t trust performance estimates. A model that performs well on data it trained on might fail on new data (overfitting). The split ensures honest evaluation:

- Training performance: How well the model learned the training data (optimistic)

- Validation performance: How well the model generalizes during development (somewhat optimistic, as development decisions optimize for it)

- Test performance: True estimate of real-world performance (most reliable)

Cross-Validation

For smaller datasets, use cross-validation instead of simple splits:

- Divide data into K folds (typically 5 or 10)

- Train on K-1 folds, validate on remaining fold

- Repeat K times, each fold serving as validation once

- Average results across all folds

This provides more reliable estimates with limited data.

Challenges and Considerations

Working with training data involves several important challenges and considerations.

Privacy and Ethics

Training data often contains personal or sensitive information, raising privacy concerns.

Issues:

- Consent: Did data subjects consent to their data being used for AI training?

- De-identification: Can individuals be re-identified from supposedly anonymized data?

- Sensitive attributes: Does data include protected information (health, financial, etc.)?

- Purpose limitation: Is training data used for purposes beyond original collection intent?

Best Practices:

- Obtain appropriate consent

- Minimize collection of sensitive information

- Apply privacy-preserving techniques

- Consider differential privacy approaches

- Regular privacy impact assessments

Bias and Fairness

Training data biases become model biases, potentially causing discriminatory outcomes.

Sources of Bias:

- Historical bias: Data reflects past discrimination

- Selection bias: Training data isn’t representative of target population

- Measurement bias: How data was collected disadvantages certain groups

- Aggregation bias: Different subgroups need different models but are treated identically

Mitigation Strategies:

- Diverse, representative data collection

- Bias testing and measurement

- Debiasing techniques

- Fairness constraints in training

- Human oversight and appeals

Cost and Scalability

Creating high-quality training data can be prohibitively expensive.

Cost Factors:

- Data collection infrastructure

- Labeling (especially expert labeling)

- Quality control

- Storage and management

- Legal compliance

Scaling Challenges:

- Some tasks require huge datasets (millions of examples)

- Rare events need many examples to see sufficient instances

- Multi-label problems multiply annotation costs

- Continuous updating as world changes

Cost Reduction Strategies:

- Active learning (intelligently select which examples to label)

- Transfer learning (reuse models trained on large datasets)

- Semi-supervised learning (leverage unlabeled data)

- Synthetic data generation

- Data augmentation

Data Quality Control

Ensuring training data quality requires systematic processes.

Quality Control Methods:

- Multiple annotators per example

- Expert review of subset

- Consistency checks

- Agreement metrics (inter-annotator agreement)

- Automated error detection

- Regular audits

Legal and Licensing Issues

Training data may be subject to copyright, licensing, or other legal restrictions.

Considerations:

- Copyright: Images, text, code may be copyrighted

- Terms of Service: Web scraping may violate ToS

- Licensing: Dataset licenses may restrict commercial use

- Regulatory: GDPR, CCPA, sector-specific regulations

- Fair use: Legal questions around training AI on copyrighted content

Best Practices:

- Review licensing for all data sources

- Obtain necessary permissions

- Respect copyright and ToS

- Consider synthetic alternatives for restricted data

- Consult legal experts

The Future of Training Data

Training data practices continue evolving with several emerging trends.

Synthetic Training Data

Generating artificial training data through simulation or generative models.

Advantages:

- Perfect labels (simulation knows ground truth)

- Unlimited quantity

- Control over diversity and edge cases

- No privacy concerns with generated people/scenarios

- Cost-effective at scale

Challenges:

- Reality gap (synthetic may not match real-world perfectly)

- Requires good simulators or generative models

- May not capture all real-world complexity

Current Use:

- Self-driving car training (simulated environments)

- Robotics (simulated physics)

- Data augmentation

- Privacy-preserving alternatives

Self-Supervised Learning

Training on data where labels are created automatically from the data itself.

Example: Language models predict next word from context—labels come from the text itself, requiring no manual annotation.

Benefits:

- Learn from massive unlabeled datasets

- Reduce labeling costs dramatically

- Often produces models that transfer well

Few-Shot Learning

Techniques enabling learning from very few examples, reducing training data requirements.

Approaches:

- Meta-learning (learning how to learn from few examples)

- Transfer learning (leveraging pre-trained models)

- Data augmentation specialized for few examples

Continual Learning

Systems that continue learning from new data after initial training, adapting to changing conditions.

Challenges:

- Catastrophic forgetting (forgetting old knowledge when learning new)

- Maintaining performance on original tasks

- Managing continuous data streams

Federated Learning

Training on distributed data without centralizing it, addressing privacy concerns.

How It Works:

- Model sent to data locations (phones, hospitals, etc.)

- Local training on local data

- Only model updates sent to central server

- Updates aggregated to improve global model

- Data never leaves local devices

Benefits:

- Privacy preservation

- Use data that can’t be centralized

- Leverage distributed data sources

Conclusion: Data Is the Foundation

Training data is the foundation upon which all machine learning is built. Algorithms, no matter how sophisticated, can only learn what training data teaches them. Quality training data leads to quality AI systems. Biased, incomplete, or inappropriate training data leads to flawed AI, regardless of algorithmic sophistication.

Understanding training data means understanding:

- What patterns an AI system has learned

- What situations it can handle well

- Where it might fail or be biased

- What limitations it has

- How it might need to improve

As AI becomes more prevalent in society, the question “What training data was used?” becomes increasingly important. It’s the question that reveals what an AI system really knows, what assumptions it makes, and whose perspectives and experiences it reflects.

For anyone working with AI, training data deserves as much attention as algorithms—perhaps more. A moderately good algorithm trained on excellent data will outperform an excellent algorithm trained on poor data. The data is the message.

For anyone evaluating AI systems, understanding training data helps ask the right questions: Is the data representative? Is it biased? Is it current? Does it match the deployment context? These questions often matter more than technical algorithm details.

Training data isn’t just a technical detail—it’s where human choices, biases, and values enter AI systems. It’s where the real world gets translated into patterns that machines learn. Understanding training data is understanding the foundation of artificial intelligence.

Every impressive AI capability you encounter—from language translation to medical diagnosis to autonomous driving—emerges from training data. Every AI limitation, failure, or bias can usually be traced back to training data. It’s not the only factor in AI success, but it’s arguably the most critical one.

Welcome to understanding the foundation of machine learning. Now when someone says “AI learns from data,” you know exactly what that means, why it matters, and what complexities lie beneath that simple statement. Training data is where AI begins, and understanding it is where your deeper comprehension of artificial intelligence begins too.