Introduction: Why Version Control is Critical for Machine Learning

Every machine learning project evolves through countless iterations. You experiment with different preprocessing techniques, try various models, adjust hyperparameters, and refine feature engineering. Without proper tracking, you quickly lose track of what worked, what didn’t, and why. You might achieve excellent results, then make changes and lose that configuration forever. You might want to collaborate with teammates but struggle to merge everyone’s contributions. You need version control.

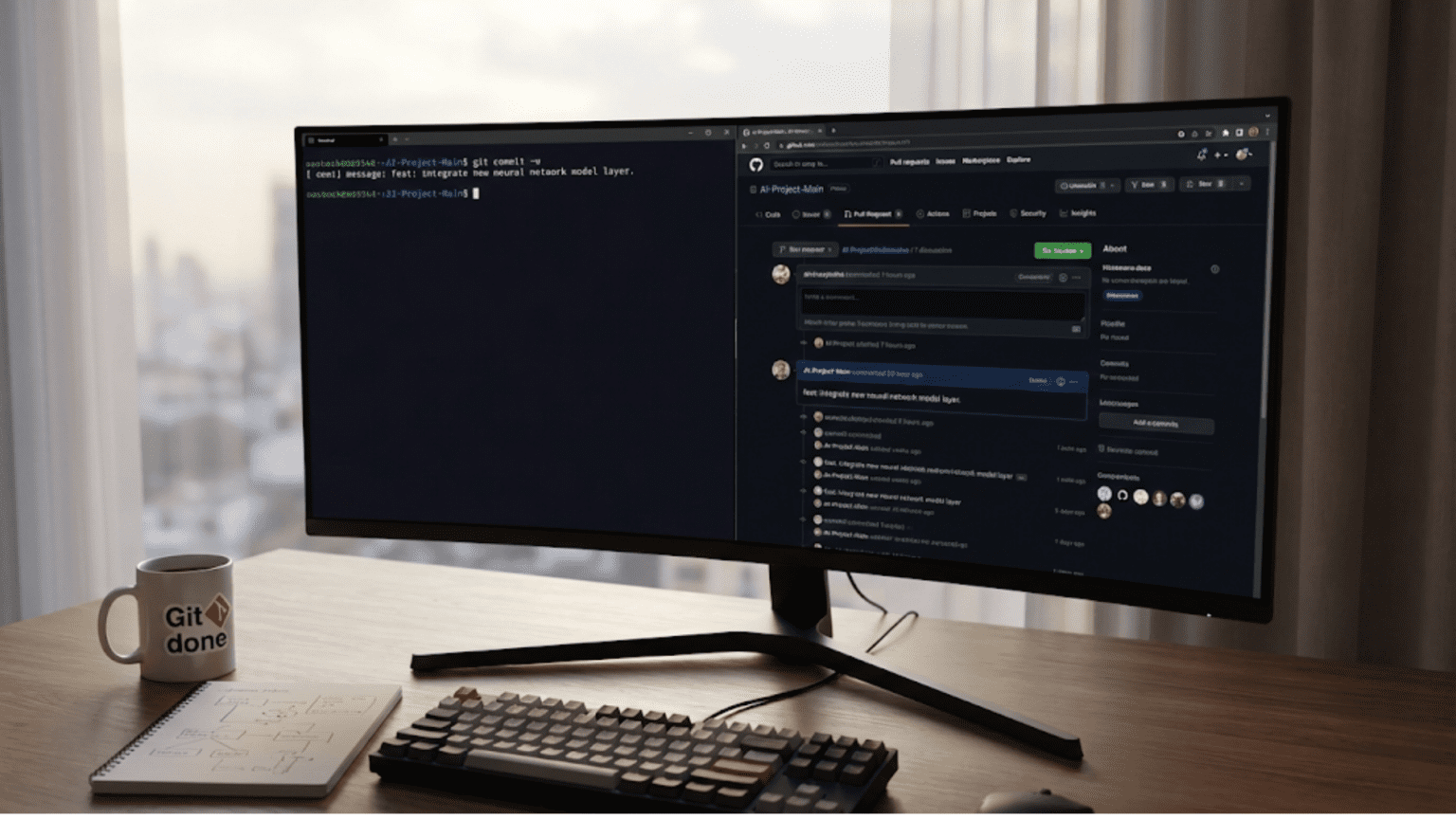

Version control systems track changes to your code over time, creating a complete history of your project’s evolution. Git is the industry-standard version control system, and GitHub is the most popular platform for hosting Git repositories and collaborating with others. Together, they provide the infrastructure for professional software development and data science work.

For machine learning practitioners, version control serves several critical purposes beyond simple code backup. It enables experimentation without fear—you can try radical changes knowing you can always return to working versions. It facilitates collaboration, allowing multiple people to work on the same project simultaneously without overwriting each other’s work. It documents your project’s history, showing exactly when you made each change and why. It enables code review, letting teammates examine and suggest improvements to your code. It supports reproducibility, ensuring others can recreate your exact environment and results.

Many machine learning practitioners initially resist version control, viewing it as overhead or complexity. This perspective changes quickly once you experience losing hours of work to an ill-advised change you can’t undo, or struggle to integrate a collaborator’s modifications. Version control isn’t overhead—it’s insurance, documentation, and collaboration infrastructure rolled into one. The time invested learning Git pays dividends throughout your career.

This comprehensive guide will transform you from a version control novice into a confident Git and GitHub user. We’ll start by understanding what version control is and why it matters specifically for machine learning. We’ll explore Git’s core concepts and mental model, which prevents confusion about how Git works. We’ll master essential Git commands for tracking changes, viewing history, and managing your work. We’ll learn branching and merging, which enable safe experimentation and parallel development. We’ll discover GitHub for collaboration, code hosting, and professional portfolio building. We’ll explore best practices specific to machine learning projects, including handling large datasets and model files. Throughout, we’ll focus on practical workflows you’ll use daily in your AI projects.

Understanding Version Control: The Core Concepts

Before diving into Git commands, you need to understand what version control fundamentally does and the mental model behind it. This conceptual foundation prevents confusion and helps you use Git effectively rather than memorizing commands blindly.

What is Version Control?

Version control is a system that records changes to files over time, allowing you to recall specific versions later. Think of it as an unlimited “undo” feature for your entire project, but much more powerful. Instead of just undoing recent changes, you can jump to any previous state, compare different versions, merge changes from multiple people, and maintain parallel versions of your project simultaneously.

Without version control, people typically manage versions manually: project_v1.py, project_v2.py, project_final.py, project_final_really.py, project_final_for_real_this_time.py. This approach quickly becomes chaotic. Which version actually worked? What changed between versions? Who made each change? Version control systems answer these questions automatically and reliably.

Why Git Dominates

Several version control systems exist—Subversion (SVN), Mercurial, Perforce—but Git has become the de facto standard, especially in data science and machine learning. Git is distributed, meaning each developer has a complete copy of the repository and its history. This enables offline work and makes operations fast since they don’t require server access.

Git was designed for speed and efficiency, even with large projects containing thousands of files. It uses clever algorithms to store changes efficiently, tracking what changed rather than storing complete copies of every file version. Git’s branching model is lightweight and flexible, encouraging experimentation and parallel development workflows.

The Git Mental Model: Snapshots, Not Differences

Understanding how Git thinks about your files prevents confusion. Unlike some systems that store changes as lists of file modifications, Git thinks of your data as a series of snapshots. When you commit changes, Git essentially takes a picture of your entire project at that moment. If files haven’t changed, Git stores a reference to the previous identical file rather than duplicating it.

This snapshot model has important implications. Each commit is a complete snapshot of your project, not just a list of changes. You can check out any commit and have a complete, working version of your project at that point in time. Branches are just pointers to specific commits. This simplicity—everything is commits, branches are pointers—makes Git’s apparent complexity more manageable.

The Three States: Working Directory, Staging Area, Repository

Git has three main states your files can be in, and understanding these states is crucial for effective Git use.

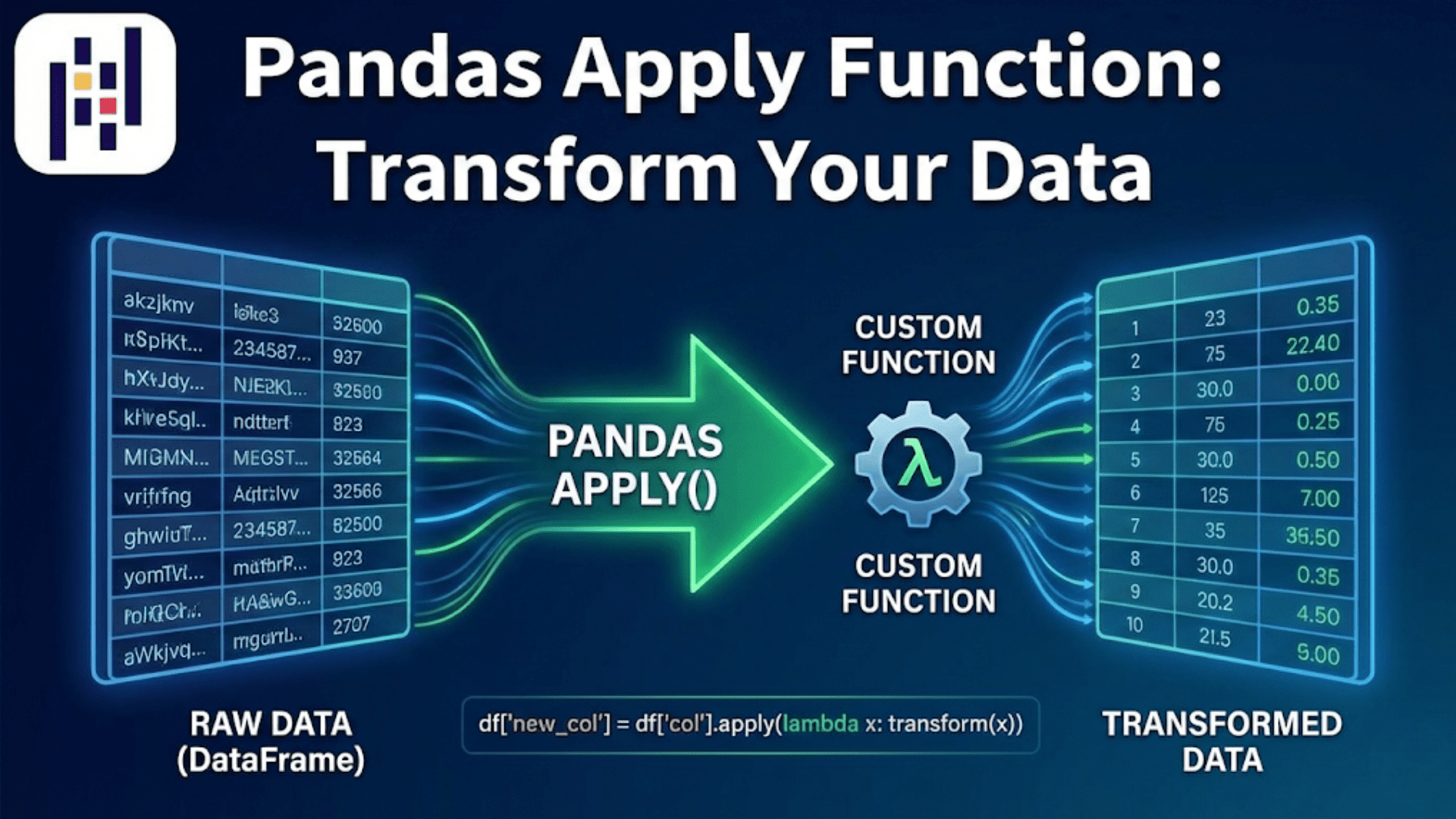

The working directory is your actual project folder where you edit files. This is what you see in your file system—your Python scripts, Jupyter notebooks, data files, etc. Changes you make here aren’t tracked until you explicitly tell Git about them.

The staging area (also called the index) is a intermediate step where you prepare changes for committing. Think of it as a holding area where you gather changes you want to save together. You might modify five files but only want to commit three of them—you stage those three, leaving the other two in the working directory.

The repository (the .git directory) is where Git permanently stores committed snapshots. Once you commit staged changes, they’re safely recorded in the repository with a unique identifier, timestamp, author information, and your commit message explaining what changed and why.

This three-stage workflow—modify in working directory, stage what you want to commit, commit staged changes to repository—might seem complex initially but provides precise control over what gets saved when.

Commits: The Building Blocks

A commit is a snapshot of your project at a specific point in time. Each commit contains the complete state of all tracked files, metadata (author, date, commit message), and a unique identifier (a 40-character SHA-1 hash like a3f5c912d8b5e7a9f3c2d1e4b8a7c6d9e2f1a0b3).

Commits link to parent commits, creating a history chain. Your first commit has no parent. Subsequent commits point to their parent (the previous commit), creating a linear history. When you merge branches, a commit can have multiple parents. This linked structure creates a directed acyclic graph (DAG) that represents your project’s complete history.

Good commit messages are crucial. A commit message should explain what changed and why, not how (the code shows how). Future you, or your teammates, will read these messages to understand the project’s evolution. A message like “fix bug” is unhelpful. “Fix off-by-one error in batch size calculation causing training instability” explains what was wrong and why it mattered.

Branches: Parallel Development

Branches in Git are incredibly lightweight—they’re just pointers to commits. Creating a branch doesn’t copy files or take up significant space; it simply creates a new pointer. This makes branching cheap and encourages its use for experimentation, feature development, and parallel work.

The default branch is typically called main (formerly master). When you create a new branch, you’re creating a new pointer that initially points to the same commit as your current branch. As you make commits on the new branch, its pointer moves forward while the original branch stays put. This enables parallel development: you can have multiple branches representing different features, experiments, or versions, all coexisting without interference.

Branches enable safe experimentation. Want to try a different model architecture? Create a branch, implement your changes, test thoroughly. If it works, merge the branch back into main. If it doesn’t, delete the branch—no harm done to your working main branch. This workflow encourages experimentation without fear of breaking working code.

Essential Git Commands: Basic Workflow

Understanding concepts is important, but proficiency requires knowing specific commands. Let’s walk through the essential Git workflow you’ll use daily.

Initializing and Configuring Git

Before using Git for the first time, configure your identity. Git attaches your name and email to every commit, so setting these is essential:

# Set your name (use your real name)

git config --global user.name "Your Name"

# Set your email (use your professional email)

git config --global user.email "your.email@example.com"

# Verify configuration

git config --listThe --global flag sets configuration for all repositories on your computer. Omitting it sets configuration only for the current repository, useful if you want different settings for work and personal projects.

To start tracking a project with Git, initialize a repository:

# Navigate to your project directory

cd /path/to/your/ml-project

# Initialize Git repository

git init

# This creates a hidden .git directory containing all Git internals

# Your project files remain unchangedAlternatively, if you’re starting from an existing GitHub repository, you clone it instead:

# Clone a repository from GitHub

git clone https://github.com/username/repository-name.git

# This creates a directory, initializes a Git repository inside it,

# downloads all repository data, and checks out the latest versionChecking Status: Understanding What’s Happening

The most frequently used Git command is git status, which shows the current state of your working directory and staging area:

git statusThis command tells you:

- Which branch you’re on

- Which files have been modified

- Which files are staged for commit

- Which files are untracked (not yet added to Git)

Example output:

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: train_model.py

Untracked files:

new_preprocessing.py

no changes added to commitRun git status frequently. It’s fast, harmless, and invaluable for understanding what’s happening. Before committing, after committing, when confused—run git status.

Tracking Changes: Add and Commit

The basic workflow for saving changes follows three steps:

Step 1: Modify files in your working directory. Edit code, create notebooks, update documentation—normal work.

Step 2: Stage changes you want to commit:

# Stage a specific file

git add train_model.py

# Stage multiple files

git add train_model.py evaluate_model.py

# Stage all changed files in current directory

git add .

# Stage all changes in repository

git add -AUse git add selectively to create logical commits. If you modified five files but they represent two different features, stage and commit them separately. Each commit should represent one logical change.

Step 3: Commit staged changes with a descriptive message:

# Commit with inline message

git commit -m "Add learning rate scheduler to improve convergence"

# Commit with detailed message (opens text editor)

git commitFor simple commits, inline messages with -m work fine. For complex changes, use git commit without -m to open your text editor where you can write a detailed, multi-paragraph message.

Complete example workflow:

# Check current status

git status

# Shows: train_model.py modified, new_preprocessing.py untracked

# Stage the modified file

git add train_model.py

# Check status again

git status

# Shows: train_model.py staged, new_preprocessing.py still untracked

# Commit with message

git commit -m "Implement early stopping with patience parameter

- Add early stopping callback to prevent overfitting

- Set default patience to 5 epochs

- Monitor validation loss for stopping criterion"

# Check status again

git status

# Shows: Working directory clean (except new_preprocessing.py still untracked)

# Stage and commit the new file

git add new_preprocessing.py

git commit -m "Add text preprocessing pipeline for NLP tasks"What this workflow demonstrates: This example shows the standard Git workflow. You modify files, check status to see what changed, stage specific changes you want to commit together, and commit with descriptive messages. Each commit represents a logical unit of work. The working directory stays clean except for intentionally untracked files.

Viewing History: Log and Diff

Understanding your project’s history is essential for debugging, learning from past decisions, and finding when bugs were introduced.

View commit history:

# Full log with all details

git log

# Compact one-line per commit

git log --oneline

# Show last 5 commits

git log -5

# Show commits with file changes

git log --stat

# Show commits affecting specific file

git log train_model.py

# Show commits by specific author

git log --author="Your Name"

# Show commits in date range

git log --since="2024-01-01" --until="2024-01-31"View changes:

# See unstaged changes (working directory vs. last commit)

git diff

# See staged changes (staging area vs. last commit)

git diff --staged

# See changes in specific file

git diff train_model.py

# Compare two commits

git diff commit1_hash commit2_hash

# Compare current state to specific commit

git diff commit_hashExample usage:

# View recent history

git log --oneline -10

# Output:

# a3f5c91 Add early stopping callback

# 7b2e4d8 Implement learning rate scheduler

# 9c1a5f3 Refactor data loading pipeline

# 4e8b2a7 Add unit tests for preprocessing

# ...

# See what changed in specific commit

git show a3f5c91

# Compare current code to version from 2 weeks ago

git diff HEAD~14Undoing Changes: Reset, Checkout, Revert

Mistakes happen—you make bad edits, commit wrong code, or want to undo changes. Git provides several mechanisms for undoing work, each appropriate for different situations.

Discard unstaged changes (working directory):

# Discard changes in specific file

git checkout -- train_model.py

# This returns the file to its last committed state

# WARNING: This is permanent - unstaged changes are lost

# Discard all unstaged changes

git checkout -- .Unstage files (move from staging area back to working directory):

# Unstage specific file (keeps changes in working directory)

git reset HEAD train_model.py

# Unstage everything

git reset HEADUndo last commit but keep changes:

# Undo commit, keep files staged

git reset --soft HEAD~1

# Undo commit, keep changes unstaged

git reset --mixed HEAD~1

# or simply

git reset HEAD~1

# Undo commit and discard changes (DANGEROUS)

git reset --hard HEAD~1Revert a commit (create new commit that undoes previous commit):

# Safer alternative to reset - doesn't rewrite history

git revert commit_hash

# Git creates a new commit that undoes the specified commit

# This is preferred when working with shared branchesWhen to use each:

checkout: Discard local changes not yet committedreset --soft: Undo commit but keep changes staged (rare usage)reset --mixed: Undo commit and unstage changes (common for fixing commit mistakes)reset --hard: Nuclear option – undo commits and discard all changes (dangerous)revert: Undo a commit in shared history (safe for collaboration)

Branching and Merging: Safe Experimentation

Branches are Git’s killer feature for machine learning development. They enable you to experiment freely, develop features in isolation, and maintain multiple versions of your project simultaneously.

Creating and Switching Branches

Create a new branch:

# Create branch from current commit

git branch feature-new-model

# Create and switch to new branch (common usage)

git checkout -b feature-new-model

# Modern Git syntax (Git 2.23+)

git switch -c feature-new-modelSwitch between branches:

# Switch to existing branch

git checkout main

# Modern syntax

git switch mainList branches:

# List local branches

git branch

# List all branches including remote

git branch -a

# List branches with last commit info

git branch -vWorking with Branches: Practical Workflow

Here’s a typical machine learning experimentation workflow using branches:

# Start on main branch

git checkout main

# Ensure main is up to date

git pull origin main

# Create branch for experiment

git checkout -b experiment-lstm-model

# Make changes to implement LSTM model

# ... edit files ...

# Stage and commit changes

git add model.py train.py

git commit -m "Implement LSTM architecture for sequence classification

- Add LSTM layers with dropout

- Configure for 128 hidden units

- Add bidirectional option"

# Continue working, making more commits

# ... more edits ...

git add utils.py

git commit -m "Add utility functions for sequence padding"

# View branch history

git log --oneline --graph

# Switch back to main to work on something else

git checkout main

# Main branch is unchanged - experiment isolated on feature branchWhat this workflow demonstrates: Branches enable non-destructive experimentation. You create a branch, work freely making multiple commits, and main remains stable. If the experiment succeeds, you merge it. If it fails, you delete the branch—no harm to main. You can switch between branches as needed, working on multiple tasks in parallel.

Merging Branches: Integrating Changes

When your experimental branch succeeds, you merge it back into main:

# Switch to branch you want to merge into (typically main)

git checkout main

# Merge the feature branch

git merge experiment-lstm-model

# If no conflicts, Git automatically creates a merge commit

# If conflicts exist, Git pauses and asks you to resolve themUnderstanding merge types:

Fast-forward merge: When main hasn’t changed since you created the branch, Git simply moves the main pointer forward. No merge commit is created—the history remains linear.

Three-way merge: When both branches have new commits, Git creates a merge commit with two parents. This preserves the history of both branches.

Merge conflicts: When the same parts of files were modified in both branches, Git can’t automatically merge them. You must manually resolve conflicts.

Resolving Merge Conflicts

Conflicts are inevitable when collaborating. Git marks conflicts in files like this:

<<<<<<< HEAD

# Code from current branch (main)

model = Sequential([

LSTM(64, return_sequences=True),

Dropout(0.2)

])

=======

# Code from branch being merged

model = Sequential([

LSTM(128, return_sequences=True),

Dropout(0.5)

])

>>>>>>> experiment-lstm-modelTo resolve:

- Open the conflicted file

- Manually edit to keep desired code (removing conflict markers)

- Stage the resolved file:

git add filename - Commit the merge:

git commit

# After resolving conflicts in all files

git add .

git commit -m "Merge experiment-lstm-model into main

Resolved conflict by keeping higher LSTM units (128) and dropout (0.5)

from experiment branch based on validation performance."Deleting Branches

After merging, delete the feature branch to keep your branch list clean:

# Delete merged branch (safe - Git prevents deleting unmerged branches)

git branch -d experiment-lstm-model

# Force delete unmerged branch (if experiment failed and you want to discard it)

git branch -D failed-experimentGitHub: Collaboration and Remote Repositories

Git manages local version control. GitHub (and alternatives like GitLab, Bitbucket) provide remote repository hosting, enabling collaboration, backup, and public code sharing.

Understanding Remote Repositories

A remote is a version of your repository hosted elsewhere—typically on GitHub’s servers. You can push your local commits to the remote, pull others’ commits from the remote, and synchronize changes between local and remote repositories.

The standard workflow involves:

- Local repository on your computer where you work

- Remote repository on GitHub as central synchronization point

- Other collaborators’ local repositories synchronized via the remote

Connecting to GitHub

Create repository on GitHub:

- Log into GitHub

- Click “New repository”

- Name it (e.g., “customer-churn-prediction”)

- Add description (optional but recommended)

- Choose public or private

- Initialize with README (optional)

- Click “Create repository”

Connect local repository to GitHub:

# Add remote (do this once per repository)

git remote add origin https://github.com/yourusername/customer-churn-prediction.git

# Verify remote was added

git remote -v

# Push initial commits to GitHub

git push -u origin main

# -u sets upstream tracking so future pushes can use just 'git push'Clone existing repository:

# Clone from GitHub to your computer

git clone https://github.com/username/repository-name.git

# This creates a directory, downloads all data, and sets up remote automatically

cd repository-name

git remote -v # Shows origin is configuredPush and Pull: Synchronizing Changes

Push sends your local commits to GitHub:

# Push current branch to GitHub

git push

# Push specific branch

git push origin main

# Push new branch to GitHub

git push -u origin feature-branchPull downloads commits from GitHub and merges them into your local branch:

# Pull latest changes from GitHub

git pull

# This is equivalent to:

# git fetch (download new commits)

# git merge (merge them into current branch)Fetch downloads changes without merging:

# Download changes but don't merge

git fetch origin

# Useful to see what changed before merging

git log origin/main

# Then merge when ready

git merge origin/mainTypical Collaborative Workflow

Here’s how teams typically work with Git and GitHub:

# Morning: Start working

git checkout main

git pull origin main # Get latest changes

# Create feature branch

git checkout -b feature-improved-preprocessing

# Work, making multiple commits

# ... edit files ...

git add preprocessing.py

git commit -m "Add text normalization function"

# ... more work ...

git add preprocessing.py tests/test_preprocessing.py

git commit -m "Add unit tests for normalization"

# Push feature branch to GitHub

git push -u origin feature-improved-preprocessing

# Create Pull Request on GitHub for team review

# ... team reviews, suggests changes ...

# Make requested changes

git add preprocessing.py

git commit -m "Use regex for more robust normalization per review feedback"

git push # Updates the same Pull Request

# After approval, merge Pull Request on GitHub

# Then update local main branch

git checkout main

git pull origin main

# Delete feature branch locally and on GitHub

git branch -d feature-improved-preprocessing

git push origin --delete feature-improved-preprocessingWhat this workflow demonstrates: Professional teams use Pull Requests (PRs) for code review before merging. You push your feature branch to GitHub, create a PR, receive feedback, make changes, and merge after approval. This ensures code quality and knowledge sharing.

.gitignore: Excluding Files

Machine learning projects often contain files you don’t want to track: large datasets, trained model files, virtual environment directories, temporary files. The .gitignore file specifies patterns for files Git should ignore.

Create .gitignore:

# In project root, create .gitignore

touch .gitignoreExample .gitignore for ML projects:

# Python

__pycache__/

*.py[cod]

*$py.class

*.so

.Python

env/

venv/

ENV/

# Jupyter Notebook

.ipynb_checkpoints

*.ipynb_checkpoints

# Data files

*.csv

*.tsv

*.parquet

data/raw/*

data/processed/*

# Model files

*.h5

*.pkl

*.pth

*.ckpt

models/

# Environment

.env

.venv

# IDE

.vscode/

.idea/

*.swp

*.swo

# OS

.DS_Store

Thumbs.dbAfter creating .gitignore:

# Add and commit it

git add .gitignore

git commit -m "Add .gitignore for Python ML project"Files already tracked by Git won’t be ignored—you must remove them first:

# Remove from Git but keep local copy

git rm --cached large_dataset.csv

git commit -m "Remove large dataset from version control"Best Practices for Machine Learning Projects

Machine learning projects have unique version control needs. Here are practices that prevent common problems:

Commit Frequently, Push Regularly

Make small, focused commits after completing logical units of work. Don’t wait until the end of the day to commit everything at once. Commit after implementing a function, fixing a bug, or completing a feature.

Push to GitHub regularly—at least daily. This creates backups and enables collaboration. If your laptop fails, your work is safe on GitHub.

Write Meaningful Commit Messages

Good messages explain what and why, not how (code shows how):

Bad messages:

- “update”

- “fix”

- “changes”

- “asdf”

Good messages:

Add dropout layers to prevent overfitting

Model was overfitting training data (98% train acc vs 72% val acc).

Added dropout layers (0.5 rate) after dense layers to improve

generalization. Validation accuracy improved to 85%.Never Commit Large Files

Git is designed for code, not large binary files. Committing large datasets or model files bloats your repository, making it slow to clone and work with.

Solutions:

- Add large files to

.gitignore - Store data separately (S3, Google Drive, data repositories)

- Use Git LFS (Large File Storage) for necessary large files

- Document how to obtain data in README

Commit Notebook Outputs Separately

Jupyter notebook JSON includes both code and output. Large outputs (plots, tables) make repositories bulky and diffs hard to read.

Best practice:

# Clear outputs before committing

# In Jupyter: Cell → All Output → Clear

# Or use nbstripout tool to automatically strip outputs

pip install nbstripout

nbstripout --install # Configures git to strip outputs automaticallyUse Branches for Experiments

Never experiment directly on main. Create branches for:

- New model architectures

- Different preprocessing approaches

- Hyperparameter optimization experiments

- Refactoring code

# Create branch for experiment

git checkout -b experiment-transformer-model

# Work freely without affecting main

# ... experiment ...

# If successful, merge back

git checkout main

git merge experiment-transformer-model

# If unsuccessful, delete branch

git branch -D experiment-transformer-modelTag Important Versions

Use tags to mark important milestones:

# Tag final model for paper submission

git tag -a v1.0 -m "Model version for ICML 2024 submission"

# Tag model deployed to production

git tag -a production-v2.1 -m "Deployed to production June 2024"

# Push tags to GitHub

git push origin --tags

# List tags

git tag -lTags create permanent bookmarks in history, making it easy to return to specific versions.

Keep README Updated

Maintain a comprehensive README explaining:

- Project purpose and goals

- Setup instructions (dependencies, data requirements)

- How to run training

- How to make predictions

- Results and performance metrics

- Team members and contributions

Good documentation makes your project accessible to others and to future you.

Conclusion: Version Control as Professional Practice

Mastering Git and GitHub transforms you from someone who codes in isolation into a professional who collaborates effectively, maintains project history, and works confidently knowing every change is tracked and recoverable. Version control isn’t just about code backup—it’s about professional development practices that enable serious machine learning work.

The skills covered in this guide—understanding Git’s mental model, using essential commands for daily work, leveraging branches for safe experimentation, collaborating through GitHub, and following machine learning-specific best practices—form the foundation of modern software development and data science workflows. These aren’t optional skills; they’re expectations in professional environments.

Git might seem complex initially with its staging area, branches, merges, and remotes. This complexity serves a purpose: it provides the flexibility and power needed for sophisticated development workflows. The mental effort learning Git pays enormous dividends. You’ll work more confidently, experiment more freely, collaborate more effectively, and maintain more professional projects.

As you continue your machine learning journey, integrate Git into your daily workflow. Create a repository for every project, even small experiments. Practice branching for new features. Push to GitHub regularly. Review your commit history to understand project evolution. Over time, Git becomes second nature—you’ll think in terms of commits, branches, and merges without conscious effort.

Remember that Git proficiency comes from regular use, not memorization. Keep this guide as a reference, consult it when needed, but most importantly, use Git actively in your projects. Start simple with basic add, commit, push workflows. Gradually incorporate branching, merging, and collaboration features. Make mistakes in practice projects where stakes are low. The confidence you build through regular use makes you a more effective machine learning practitioner and a more attractive collaborator and hire.

Version control distinguishes hobbyists from professionals. By mastering Git and GitHub, you demonstrate technical competence, collaborative readiness, and professional discipline—qualities that matter as much as machine learning expertise in building a successful career in artificial intelligence.