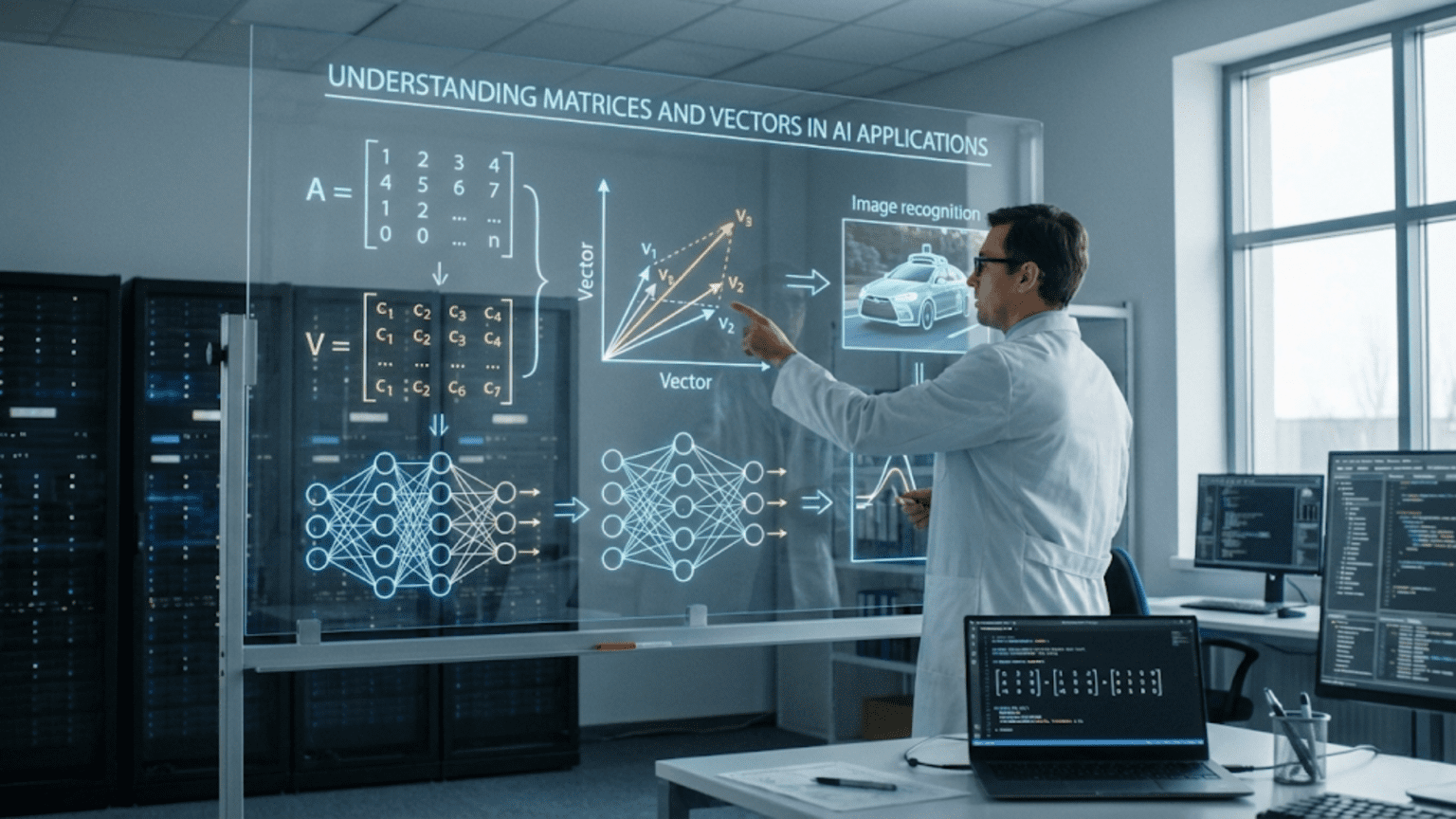

If you’ve learned about matrices and vectors from a mathematical perspective, you might still be wondering: “Okay, but what do these actually do in artificial intelligence?” The abstract mathematical definitions—arrays of numbers, linear transformations, dot products—don’t immediately reveal how these concepts power the AI systems you interact with daily.

The truth is that matrices and vectors aren’t just mathematical abstractions in AI—they’re the fundamental way that data, models, and computations are represented and manipulated. Every image you upload, every word a language model processes, every recommendation Netflix makes, every prediction a neural network produces—all of these involve matrices and vectors working behind the scenes.

In this article, we’ll explore exactly how matrices and vectors are used in real AI applications. Rather than focusing on abstract mathematics, we’ll look at concrete examples that show why these structures are so perfectly suited to artificial intelligence. You’ll see how images become matrices, how words become vectors, how neural networks use matrices for computation, and how these mathematical objects enable the AI capabilities that seem almost magical.

By understanding these practical applications, you’ll gain insight into how AI actually works—not just what it can do, but how it does it. Let’s dive into the real-world applications of matrices and vectors in artificial intelligence.

Images as Matrices: Computer Vision Foundations

One of the most intuitive applications of matrices in AI is representing images. An image is literally a matrix of numbers.

Grayscale Images

A grayscale image is a 2D matrix where each element represents one pixel’s brightness value.

Example: 5×5 Grayscale Image

[245 240 238 242 246]

[238 235 230 234 240]

[230 225 220 222 228]

[225 220 215 218 224]

[220 215 210 212 218]

Each number (typically 0-255) represents how bright that pixel is:

- 0 = black

- 255 = white

- Values in between = shades of gray

A real image might be 1920×1080 (Full HD), which is a matrix with 1,920 rows and 1,080 columns—over 2 million numbers!

Color Images: Three Matrices

A color image has three color channels (Red, Green, Blue), so it’s represented by three matrices stacked together:

Red Channel: Green Channel: Blue Channel:

[245 240 238] [200 195 190] [180 175 170]

[238 235 230] [195 190 185] [175 170 165]

[230 225 220] [190 185 180] [170 165 160]

Each pixel’s color is the combination of its Red, Green, and Blue values. This 3D structure (height × width × channels) is technically a tensor, but it’s built from three matrices.

Image Operations as Matrix Operations

Common image processing operations are matrix operations:

Brightness adjustment: Add a constant to every matrix element

brighter_image = original_image + 50

Contrast adjustment: Multiply every element by a constant

higher_contrast = original_image * 1.5

Flip horizontal: Reverse the order of columns

flipped = image[:, ::-1]

Crop: Extract a sub-matrix

cropped = image[100:300, 200:400] # rows 100-300, columns 200-400

Blur: Each pixel becomes the average of surrounding pixels (convolution with a matrix)

Convolutional Neural Networks

When AI processes images, it uses convolutional layers that apply filters—small matrices that slide across the image:

Filter (3×3 matrix): Image patch: Result:

[-1 -1 -1] [100 150 120]

[ 0 0 0] × [110 140 130] = Edge detection value

[ 1 1 1] [120 130 140]

The filter is a matrix, the image patch is a matrix, and the operation (element-wise multiply and sum) produces a number indicating whether an edge is present. This happens millions of times as the filter slides across the entire image, and the network learns the best filter values for detecting patterns.

Real Application: Face Recognition

When a face recognition system processes your photo:

- Input: Image converted to matrix (or tensor with RGB channels)

- Convolutional layers: Multiple filter matrices detect features (edges, shapes, textures)

- Pooling: Reduce matrix size while preserving important information

- Fully connected layers: Flatten matrices to vectors, multiply by weight matrices

- Output: Vector of numbers representing your face’s unique characteristics

The entire pipeline is matrices transforming into other matrices, eventually producing a feature vector that uniquely represents your face.

Words as Vectors: Natural Language Processing

One of the most fascinating applications of vectors in AI is representing words as vectors of numbers—word embeddings.

The Challenge

Computers work with numbers, not words. How do we convert text into numbers for machine learning?

Bad approach: Number words alphabetically

- “apple” = 1

- “banana” = 2

- “zebra” = 26

This doesn’t capture meaning. “apple” and “banana” are similar (both fruits), but their numbers don’t reflect this.

Word Embeddings: Words as Vectors

Word embeddings represent each word as a vector in high-dimensional space (typically 100-300 dimensions) where similar words have similar vectors.

Example (simplified to 4 dimensions for illustration):

"king" = [0.5, 0.8, -0.3, 0.6]

"queen" = [0.5, 0.7, -0.4, 0.5]

"man" = [0.6, 0.2, 0.1, 0.3]

"woman" = [0.6, 0.1, 0.0, 0.2]

"dog" = [-0.3, 0.2, 0.8, -0.4]

"puppy" = [-0.3, 0.1, 0.7, -0.5]

Notice:

- “king” and “queen” have similar vectors (royal terms)

- “man” and “woman” have similar vectors (human terms)

- “dog” and “puppy” have similar vectors (canine terms)

- Royal terms differ significantly from animal terms

Vector Arithmetic with Meaning

Amazingly, vector math captures semantic relationships:

"king" - "man" + "woman" ≈ "queen"

This works! Subtracting the “male” concept and adding the “female” concept transforms “king” to “queen.”

More examples:

"Paris" - "France" + "Italy" ≈ "Rome"

"walking" - "walk" + "swim" ≈ "swimming"

The vector arithmetic captures conceptual relationships.

How Embeddings Are Learned

Models learn embeddings by training on text where words appearing in similar contexts get similar vectors:

- “The cat sat on the mat” and “The dog sat on the mat”

- Since “cat” and “dog” appear in similar contexts, they get similar vectors

Training on billions of words from the internet creates embeddings capturing rich semantic relationships.

Sentence and Document Vectors

We can extend vectors beyond individual words:

Sentence vector: Average or learned combination of word vectors

"The dog ran" = average([vector("the"), vector("dog"), vector("ran")])

Document vector: Represents entire document in vector space

These enable:

- Semantic search: Find documents similar to a query

- Sentiment analysis: Vector points toward positive or negative region

- Text classification: Vector’s position determines category

Real Application: Language Translation

When Google Translate converts “Hello” to “Bonjour”:

- Encode: “Hello” becomes a vector in English embedding space

- Transform: Vector is transformed (via learned matrix) to French embedding space

- Decode: Find French word with closest vector → “Bonjour”

The entire translation process is vector and matrix operations!

Transformers and Attention

Modern language models (GPT, BERT) use transformers, which heavily leverage vectors and matrices:

Query, Key, Value vectors: Each word becomes three different vectors

Attention scores: Computed using matrix multiplication

Attention = softmax(Q × K^T / √d) × V

Where Q, K, V are matrices containing query, key, and value vectors for all words.

This single matrix operation determines which words should “attend to” (focus on) which other words—the key mechanism enabling modern NLP breakthroughs.

Recommendation Systems: Matrix Factorization

Matrices are central to recommendation systems like Netflix, Amazon, and Spotify use.

The Rating Matrix

Imagine a matrix where rows are users, columns are items, and values are ratings:

Movie1 Movie2 Movie3 Movie4 Movie5

User1 5 ? 4 ? 3

User2 ? 4 ? 5 4

User3 3 3 ? ? ?

User4 ? 5 4 4 ?

The “?” marks are missing—users haven’t rated these items. The recommendation problem: fill in the missing values to predict what users will like.

Matrix Factorization

The idea: decompose the large, sparse rating matrix into two smaller, dense matrices:

Rating Matrix (users × items) ≈ User Matrix (users × factors) × Item Matrix (factors × items)

Example:

[M1 M2 M3 M4] [F1 F2] [F1 F2 F1 F2]

User1 [5 3 4 2] [0.9 0.2] [5.0 3.0 4.0 2.0]

User2 [4 3 5 3] ≈ [0.8 0.3] × [0.5 0.1 0.8 0.2]

User3 [2 5 3 4] [0.3 0.9] [...]

[... ... ...]

Each user gets a vector of “factor values” (preferences for latent factors like “action vs. romance” or “old vs. new”). Each item gets a vector of “factor values” (how much it has of each factor).

Predicting a rating:

Predicted rating = User_vector · Item_vector (dot product)

The dot product of user and item vectors predicts how much that user will like that item!

Why This Works

The factors capture hidden patterns:

- Factor 1 might represent “action-oriented”

- Factor 2 might represent “family-friendly”

- A user with high Factor 1 and low Factor 2 likes action movies

- A movie with high Factor 1 is an action movie

- Their dot product will be high → good recommendation

Real Application: Netflix

When Netflix recommends a show:

- User vector: Your viewing history produces a vector of latent preferences

- Item vectors: Every show has a learned vector of characteristics

- Prediction: Dot product of your vector with each show’s vector

- Recommendation: Shows with highest predicted ratings

All matrix and vector operations!

Collaborative Filtering Extensions

More sophisticated approaches:

- Factorization Machines: Incorporate additional features beyond user/item IDs

- Neural Collaborative Filtering: Use neural networks to learn non-linear relationships

- Hybrid Systems: Combine matrix factorization with content-based features

All rely on representing users and items as vectors and using vector operations to compute predictions.

Neural Networks: Matrices All the Way Down

Neural networks are essentially sequences of matrix operations. Understanding this demystifies how they work.

Input as Vector

Data enters a neural network as a vector:

Image: Flatten pixels into a long vector

28×28 image → 784-element vector

Text: Word embeddings become sequence of vectors

Tabular data: Each row is already a feature vector

Weight Matrices

Each neural network layer has a weight matrix. For a layer connecting 784 inputs to 128 outputs:

W = 784×128 matrix (100,352 numbers!)

b = 128-element bias vector

Forward Propagation

Computing layer output:

Output = activation(W × Input + b)

This single line represents the entire layer computation:

- Matrix-vector multiplication: W × Input (all neurons computed in parallel)

- Add bias: + b (broadcast addition)

- Activation function: Applied element-wise (ReLU, sigmoid, etc.)

Example: Simple Network

Input layer: 4 features Hidden layer: 3 neurons Output layer: 2 neurons

# Input vector

x = [1.0, 0.5, -0.3, 0.8]

# First layer

W1 = [[0.2, 0.3, -0.1, 0.4], # Neuron 1 weights

[0.1, -0.2, 0.5, 0.2], # Neuron 2 weights

[-0.3, 0.4, 0.1, -0.2]] # Neuron 3 weights

b1 = [0.1, -0.1, 0.2]

h = activation(W1 × x + b1) # Hidden layer output (3 values)

# Second layer

W2 = [[0.5, -0.3, 0.2], # Output neuron 1 weights

[-0.4, 0.6, 0.1]] # Output neuron 2 weights

b2 = [0.0, 0.1]

output = activation(W2 × h + b2) # Final output (2 values)

The entire network: two matrix multiplications with activations!

Batch Processing

Real networks process multiple inputs simultaneously using matrices:

Outputs = activation(W × Inputs + B)

Where:

- Inputs: Matrix (batch_size × input_features)

- W: Weight matrix (input_features × output_features)

- B: Bias matrix (batch_size × output_features)

- Outputs: Matrix (batch_size × output_features)

Processing 100 examples simultaneously is barely slower than processing 1, thanks to matrix operations optimized on GPUs!

Convolutional Layers

Convolutional layers use small weight matrices (filters) applied across the image:

Filter matrix (3×3):[w1 w2 w3]

[w4 w5 w6]

[w7 w8 w9]

This 9-number matrix slides across the image, performing matrix operations at each position. A single convolutional layer might have 64 different filter matrices, each learning different patterns.

Real Application: Image Classification

Classifying a cat photo:

- Input: Image as matrix (or RGB tensor)

- Conv Layer 1: 32 filter matrices detect low-level features

- Output: 32 feature matrices (one per filter)

- Conv Layer 2: 64 filters find higher-level patterns

- Fully Connected: Flatten to vector, multiply by weight matrix

- Output: Vector of class probabilities [0.9, 0.05, 0.03, 0.02] (90% cat)

Every step involves matrices and vectors!

Dimensionality Reduction: Matrices Simplify Data

When data has too many features, we use matrices to reduce dimensions while preserving information.

The Problem

Dataset with 1000 features:

- Hard to visualize

- Computationally expensive

- May contain redundant information

- Risk of overfitting

Solution: Reduce to 50 features while keeping most information.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA uses matrix operations to find new features that capture maximum variance:

- Data matrix: X (samples × features)

- Covariance matrix: Measures how features vary together

- Eigenvectors: Computed from covariance matrix

- Principal components: Eigenvectors are the new feature directions

- Transform: Multiply data by eigenvector matrix to get reduced representation

Matrix operation:

X_reduced = X × Eigenvector_matrix

Where Eigenvector_matrix contains top k eigenvectors (columns).

Geometric Interpretation

Imagine data in 3D space, but all points roughly lie on a 2D plane:

- Original data: 3D vectors

- PCA finds the 2D plane’s orientation (two eigenvector directions)

- Projects data onto this plane (matrix multiplication)

- Reduced data: 2D vectors (less storage, same information)

Real Application: Face Recognition

Eigenfaces technique for face recognition:

- Face dataset: Each face is a vector (flattened pixel values)

- Face matrix: Stack all face vectors as rows

- PCA: Find eigenvectors (eigenfaces) that capture facial variation

- Representation: Each face as a vector of eigenface coefficients

- Recognition: Compare coefficient vectors (much smaller than original images)

A 100×100 face image (10,000 pixels) might be represented by just 50 eigenface coefficients—200× reduction while keeping identity information!

t-SNE for Visualization

Another dimensionality reduction technique using matrices:

t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding):

- Preserves local structure (nearby points stay nearby)

- Reduces to 2D or 3D for visualization

- Involves matrix operations on pairwise distances

Used to visualize:

- Word embeddings in 2D

- High-dimensional data clusters

- Neural network internal representations

Similarity and Distance: Vector Operations

Many AI tasks require measuring similarity or distance between data points, which are vector operations.

Cosine Similarity

Measures similarity based on vector direction (ignoring magnitude):

similarity = (v1 · v2) / (||v1|| × ||v2||)

Where:

- v1 · v2 is dot product

- ||v|| is vector length (norm)

Result ranges from -1 (opposite) to 1 (identical).

Applications:

Document similarity: Treat documents as vectors of word frequencies

Doc1: [word1_count, word2_count, ...]

Doc2: [word1_count, word2_count, ...]

similarity = cosine_similarity(Doc1, Doc2)

Recommendation systems: Find users with similar preference vectors

Plagiarism detection: Compare document vectors

Search engines: Compare query vector to document vectors

Euclidean Distance

Measures straight-line distance between vectors:

distance = √[(v1₁-v2₁)² + (v1₂-v2₂)² + ... + (v1ₙ-v2ₙ)²]

Or in vector notation: ||v1 – v2||

Applications:

K-Nearest Neighbors: Find k closest training examples (smallest distances)

Clustering: Group points with small mutual distances

Anomaly detection: Flag points far from others (large distances)

Image similarity: Pixel vectors with small distances look similar

Real Application: Semantic Search

When searching “deep learning tutorials”:

- Query vector: “deep learning tutorials” → embedding vector

- Document vectors: Each indexed document has a vector

- Similarity: Compute cosine similarity between query and all documents

- Ranking: Return documents with highest similarity

This finds semantically similar documents even if they don’t contain exact keywords!

Transformations and Feature Engineering

Matrices transform data from one space to another—crucial for feature engineering and data preprocessing.

Standardization Matrix

Centering and scaling features:

X_standardized = (X - mean_vector) / std_vector

Can be implemented as matrix operations, especially for multiple features simultaneously.

Rotation and Augmentation

For computer vision, data augmentation applies transformations:

Rotation matrix (2D):

[cos(θ) -sin(θ)][sin(θ) cos(θ)]

Multiply each point (x, y) by this matrix to rotate by angle θ.

Affine transformations: General transformations combining rotation, scaling, translation:

New_image = Transformation_matrix × Original_image + Translation_vector

Feature Crosses

Creating interaction features:

Original features: [x1, x2] Expanded features: [x1, x2, x1×x2, x1², x2²]

This can be viewed as transforming the feature vector through a non-linear mapping, though it’s often implemented explicitly.

Real Application: Data Preprocessing Pipeline

Before training a model:

- Raw data matrix: X_raw (samples × features)

- Handle missing values: Matrix operations to fill or remove

- Standardize: X_scaled = (X_raw – μ) / σ (vectorized operation)

- Create polynomial features: Transform to higher-dimensional space

- PCA: Reduce dimensions if needed

- Result: X_processed ready for training

Each step involves vector or matrix operations on the entire dataset efficiently!

Optimization: Gradient Vectors

Training AI models requires optimization, where gradients are crucial vectors.

The Gradient Vector

The gradient is a vector of partial derivatives showing how to change parameters to reduce error:

∇Loss = [∂Loss/∂w1, ∂Loss/∂w2, ..., ∂Loss/∂wn]

It points in the direction of steepest increase. Moving opposite to the gradient reduces loss.

Gradient Descent Update

Update parameters using the gradient vector:

w_new = w_old - learning_rate × ∇Loss

This is vector subtraction (and scalar multiplication)!

Example with 3 parameters:

w_old = [0.5, -0.3, 0.8]

gradient = [0.1, -0.2, 0.05]

learning_rate = 0.01

w_new = [0.5, -0.3, 0.8] - 0.01 × [0.1, -0.2, 0.05]

= [0.5, -0.3, 0.8] - [0.001, -0.002, 0.0005]

= [0.499, -0.298, 0.7995]

Batch Gradient Computation

For neural networks with millions of parameters:

Gradients = Matrix of partial derivatives (same shape as weights)

The gradient computation for weight matrix W:

∂Loss/∂W = (∂Loss/∂Output) × Input^T

This is matrix multiplication! The entire backpropagation algorithm is sequences of matrix operations.

Real Application: Training Deep Networks

Training a neural network:

- Forward pass: Matrix multiplications compute predictions

- Loss: Scalar measuring error

- Backward pass: Matrix multiplications compute gradients

- Update: Vector/matrix operations update all parameters

- Repeat: Thousands of iterations

All operations are matrix and vector manipulations, enabling efficient training on GPUs.

Attention Mechanisms: The Power of Matrices

Attention mechanisms, fundamental to transformers and modern NLP, are essentially matrix operations.

Attention Concept

When processing “The cat sat on the mat”, determining that “sat” relates more to “cat” than to “mat” requires attention.

Attention as Matrix Operation

Self-attention computes relationships between all words:

- Input: Matrix of word vectors (sequence_length × embedding_dim)

- Query, Key, Value: Three transformations of input (via learned matrices)

Q = Input × W_query

K = Input × W_key

V = Input × W_value

- Attention scores: Matrix multiplication and softmax

Attention = softmax(Q × K^T / √d)

This produces a matrix where element (i,j) shows how much word i attends to word j.

- Output: Weighted combination of values

Output = Attention × V

The entire attention mechanism is matrix multiplications!

Multi-Head Attention

Transformer models use multiple attention “heads” in parallel:

- Multiple sets of Q, K, V weight matrices

- Each head learns different relationship types

- Outputs concatenated and transformed again (matrix operation)

All implemented as efficient matrix operations on GPUs.

Real Application: Machine Translation

Translating “I love machine learning” to French:

- Encoder: Self-attention matrices relate English words to each other

- Decoder: Self-attention relates French words being generated

- Cross-attention: Matrices relate French words to English words

- Output: Each step produces a vector of word probabilities

The entire translation is sequences of matrix operations on word vector matrices!

Conclusion: Matrices and Vectors Are AI’s Language

Matrices and vectors aren’t just convenient mathematical notation for AI—they’re the fundamental way that data, computations, and transformations are represented and executed:

Images are matrices where each element represents pixel information

Words are vectors in semantic space where position encodes meaning

Neural networks are sequences of matrix multiplications that transform inputs to outputs

Recommendations emerge from factoring user-item matrices into latent factor vectors

Similarities are computed through vector dot products and norms

Training happens through gradient vectors guiding parameter updates

Attention mechanisms use matrices to determine what information to focus on

Understanding these applications reveals why linear algebra is so central to AI. It’s not that AI researchers arbitrarily chose matrices and vectors—it’s that these mathematical objects perfectly match the structure of AI problems:

- Data comes in array form (images, text embeddings, datasets)

- Computations are parallelizable (process all data simultaneously)

- Transformations are systematic (apply same operations across data)

- Hardware is optimized for it (GPUs excel at matrix operations)

Every impressive AI capability you encounter—from recognizing faces to translating languages to generating images—ultimately reduces to matrices and vectors being manipulated through linear algebra operations. The seemingly magical intelligence emerges from these simple mathematical structures combined in deep, complex architectures.

When you understand how matrices represent images, how vectors capture word meanings, how matrix multiplication implements neural computation, you’re not just learning mathematics—you’re understanding the fundamental language of artificial intelligence itself. These aren’t abstract concepts disconnected from real applications; they’re the actual implementation of every AI system that exists.

The next time you see an AI system work, you can think: somewhere in that system, matrices are multiplying, vectors are being compared, and linear algebra is enabling what appears to be intelligent behavior. You now understand not just that AI uses mathematics, but exactly how matrices and vectors make modern artificial intelligence possible.