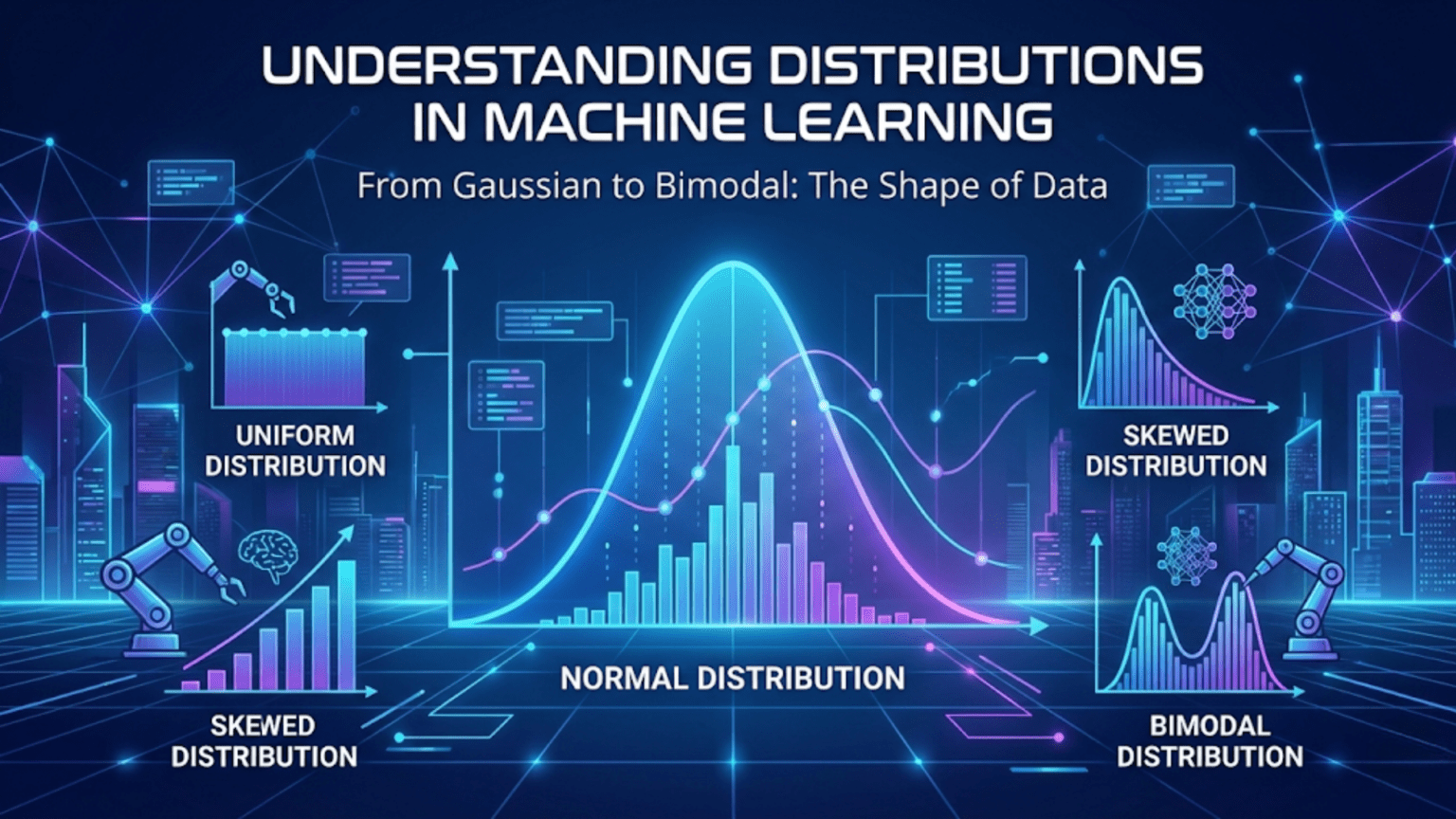

Introduction: Why Distributions Matter in Machine Learning

Probability distributions are mathematical functions that describe the likelihood of different outcomes in a random process. They form the theoretical backbone of machine learning, appearing in every phase from data preprocessing to model training and evaluation. When you generate synthetic data, you sample from distributions. When you train a neural network, you often initialize weights from specific distributions. When you build a probabilistic classifier, you model the likelihood of classes using distributions. Understanding distributions is not optional for serious machine learning practitioners—it is fundamental.

Different types of data and phenomena follow different distributions. The heights of adults follow a normal distribution, clustering around an average with symmetric tails. The number of customers arriving at a store each hour follows a Poisson distribution. The time between earthquake events follows an exponential distribution. Recognizing which distribution best describes your data allows you to choose appropriate models, make valid statistical inferences, and generate realistic synthetic data.

This article provides a comprehensive tour of the probability distributions you will encounter most frequently in machine learning. We will explore both discrete distributions, which describe countable outcomes like the number of heads in coin flips, and continuous distributions, which describe measurable quantities like height or temperature. For each distribution, we will examine its mathematical properties, visualize its shape, implement it in Python, and discuss its applications in machine learning. By the end, you will understand not just the mechanics of different distributions but also how to recognize them in your data and leverage them in your models.

The Normal Distribution: The Bell Curve

The normal distribution, also called the Gaussian distribution, is perhaps the most important distribution in statistics and machine learning. Its characteristic bell shape appears throughout nature and data science. Many real-world phenomena, from measurement errors to biological traits, approximately follow this distribution.

The normal distribution is characterized by two parameters: the mean μ (mu), which determines the center of the distribution, and the variance σ² (sigma squared) or standard deviation σ, which controls the spread. The probability density function is:

This equation might look intimidating, but it simply describes a smooth, symmetric, bell-shaped curve centered at μ. The exponential term ensures that values far from the mean have rapidly decreasing probability density, creating the characteristic tails of the distribution.

Several properties make the normal distribution special. First, it is completely symmetric around the mean. The probability of being a certain distance above the mean equals the probability of being the same distance below it. Second, the mean, median, and mode are all equal and located at the center. Third, about 68% of values fall within one standard deviation of the mean, about 95% within two standard deviations, and about 99.7% within three standard deviations. This 68-95-99.7 rule provides a quick way to interpret standard deviation and identify outliers.

The central limit theorem explains why normal distributions appear so frequently. This fundamental theorem states that the sum or average of many independent random variables tends toward a normal distribution, regardless of the original distributions of those variables. Since many real-world quantities result from numerous small, independent effects, they naturally approximate normality.

Let’s implement and visualize the normal distribution:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import stats

# Create a range of x values

x = np.linspace(-10, 10, 1000)

# Define several normal distributions with different parameters

distributions = [

(0, 1, 'μ=0, σ=1 (Standard Normal)'),

(0, 2, 'μ=0, σ=2'),

(0, 0.5, 'μ=0, σ=0.5'),

(2, 1, 'μ=2, σ=1'),

]

# Plot all distributions

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

for mu, sigma, label in distributions:

pdf = stats.norm.pdf(x, mu, sigma)

plt.plot(x, pdf, linewidth=2, label=label)

plt.xlabel('Value')

plt.ylabel('Probability Density')

plt.title('Normal Distributions with Different Parameters')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

# Demonstrate the 68-95-99.7 rule

print("The 68-95-99.7 Rule for Standard Normal Distribution")

print("=" * 60)

mu, sigma = 0, 1

# Calculate probabilities for different ranges

prob_1sigma = stats.norm.cdf(mu + sigma, mu, sigma) - stats.norm.cdf(mu - sigma, mu, sigma)

prob_2sigma = stats.norm.cdf(mu + 2*sigma, mu, sigma) - stats.norm.cdf(mu - 2*sigma, mu, sigma)

prob_3sigma = stats.norm.cdf(mu + 3*sigma, mu, sigma) - stats.norm.cdf(mu - 3*sigma, mu, sigma)

print(f"Probability within 1 standard deviation: {prob_1sigma:.4f} ({prob_1sigma*100:.2f}%)")

print(f"Probability within 2 standard deviations: {prob_2sigma:.4f} ({prob_2sigma*100:.2f}%)")

print(f"Probability within 3 standard deviations: {prob_3sigma:.4f} ({prob_3sigma*100:.2f}%)")

print()

# Generate random samples and verify they follow the distribution

np.random.seed(42)

samples = np.random.normal(mu, sigma, 10000)

print("Verification with Random Samples (n=10,000)")

print("=" * 60)

print(f"Theoretical mean: {mu}, Sample mean: {np.mean(samples):.4f}")

print(f"Theoretical std: {sigma}, Sample std: {np.std(samples, ddof=1):.4f}")

print()

# Visual verification

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 5))

# Histogram with theoretical curve

axes[0].hist(samples, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.7,

edgecolor='black', color='skyblue', label='Sample data')

x_plot = np.linspace(samples.min(), samples.max(), 100)

axes[0].plot(x_plot, stats.norm.pdf(x_plot, mu, sigma),

'r-', linewidth=2, label='Theoretical PDF')

axes[0].set_xlabel('Value')

axes[0].set_ylabel('Density')

axes[0].set_title('Histogram vs Theoretical Distribution')

axes[0].legend()

axes[0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Q-Q plot to check normality

stats.probplot(samples, dist="norm", plot=axes[1])

axes[1].set_title('Q-Q Plot (Quantile-Quantile)')

axes[1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()In machine learning, the normal distribution appears in numerous contexts. Many algorithms assume that data or errors follow a normal distribution. Linear regression assumes that residuals are normally distributed. Naive Bayes classifiers for continuous features often assume Gaussian distributions. Principal component analysis seeks directions of maximum variance, which relates to the covariance structure of multivariate normal distributions. When initializing neural network weights, we often sample from normal distributions to break symmetry while keeping initial values reasonable.

The Standard Normal Distribution and Z-Scores

A special case of the normal distribution deserves particular attention: the standard normal distribution, which has mean 0 and standard deviation 1. This distribution is denoted as N(0, 1) and serves as a reference distribution for statistical inference.

Any normal distribution can be transformed into the standard normal distribution through standardization or z-score transformation:

The z-score tells you how many standard deviations a value is from the mean. A z-score of 2 means the value is two standard deviations above the mean. A z-score of -1.5 means it is one and a half standard deviations below the mean. Z-scores allow you to compare values from different normal distributions on a common scale.

In machine learning, standardization using z-scores is one of the most common preprocessing steps. Many algorithms, including support vector machines, k-nearest neighbors, and neural networks, perform better when features are standardized because it puts all features on the same scale and prevents features with larger ranges from dominating the learning process.

Let’s demonstrate z-score transformation:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import stats

# Generate data from different normal distributions

np.random.seed(42)

height_cm = np.random.normal(170, 10, 1000) # Heights in cm, mean=170, std=10

weight_kg = np.random.normal(70, 15, 1000) # Weights in kg, mean=70, std=15

print("Before Standardization")

print("=" * 60)

print(f"Height: mean={np.mean(height_cm):.2f}, std={np.std(height_cm, ddof=1):.2f}")

print(f"Weight: mean={np.mean(weight_kg):.2f}, std={np.std(weight_kg, ddof=1):.2f}")

print()

# Standardize using z-scores

height_z = (height_cm - np.mean(height_cm)) / np.std(height_cm, ddof=1)

weight_z = (weight_kg - np.mean(weight_kg)) / np.std(weight_kg, ddof=1)

print("After Standardization (Z-scores)")

print("=" * 60)

print(f"Height: mean={np.mean(height_z):.6f}, std={np.std(height_z, ddof=1):.6f}")

print(f"Weight: mean={np.mean(weight_z):.6f}, std={np.std(weight_z, ddof=1):.6f}")

print()

# Visualize the transformation

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(14, 10))

# Original height distribution

axes[0, 0].hist(height_cm, bins=30, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='lightblue')

axes[0, 0].axvline(np.mean(height_cm), color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2, label='Mean')

axes[0, 0].set_xlabel('Height (cm)')

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Frequency')

axes[0, 0].set_title('Original Height Distribution')

axes[0, 0].legend()

axes[0, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Original weight distribution

axes[0, 1].hist(weight_kg, bins=30, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='lightcoral')

axes[0, 1].axvline(np.mean(weight_kg), color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2, label='Mean')

axes[0, 1].set_xlabel('Weight (kg)')

axes[0, 1].set_ylabel('Frequency')

axes[0, 1].set_title('Original Weight Distribution')

axes[0, 1].legend()

axes[0, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Standardized height distribution

axes[1, 0].hist(height_z, bins=30, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='lightblue')

axes[1, 0].axvline(0, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2, label='Mean=0')

axes[1, 0].axvline(-1, color='orange', linestyle='--', linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.7, label='±1 SD')

axes[1, 0].axvline(1, color='orange', linestyle='--', linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.7)

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel('Z-score')

axes[1, 0].set_ylabel('Frequency')

axes[1, 0].set_title('Standardized Height Distribution')

axes[1, 0].legend()

axes[1, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Standardized weight distribution

axes[1, 1].hist(weight_z, bins=30, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='lightcoral')

axes[1, 1].axvline(0, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2, label='Mean=0')

axes[1, 1].axvline(-1, color='orange', linestyle='--', linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.7, label='±1 SD')

axes[1, 1].axvline(1, color='orange', linestyle='--', linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.7)

axes[1, 1].set_xlabel('Z-score')

axes[1, 1].set_ylabel('Frequency')

axes[1, 1].set_title('Standardized Weight Distribution')

axes[1, 1].legend()

axes[1, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Practical example: outlier detection using z-scores

print("Outlier Detection Using Z-scores")

print("=" * 60)

threshold = 3 # Common threshold: values beyond ±3 standard deviations

height_outliers = np.abs(height_z) > threshold

weight_outliers = np.abs(weight_z) > threshold

print(f"Height outliers (|z| > {threshold}): {np.sum(height_outliers)}")

print(f"Weight outliers (|z| > {threshold}): {np.sum(weight_outliers)}")

print()

if np.sum(height_outliers) > 0:

print("Height outlier values (original scale):")

print(height_cm[height_outliers])This implementation shows how standardization transforms different distributions to a common scale, which is essential for many machine learning algorithms that are sensitive to feature magnitudes.

Discrete Distributions: Bernoulli and Binomial

While the normal distribution describes continuous data, discrete distributions describe countable outcomes. The Bernoulli and binomial distributions are fundamental discrete distributions that model binary events.

Bernoulli Distribution

The Bernoulli distribution models a single trial with two possible outcomes: success (1) or failure (0). It has one parameter p, the probability of success. The probability mass function is:

The mean of a Bernoulli distribution is E[X] = p, and the variance is Var(X) = p(1 – p). Notice that variance is maximized when p = 0.5, meaning the outcome is most uncertain when both outcomes are equally likely.

In machine learning, Bernoulli distributions model binary classification problems. Each prediction can be viewed as a Bernoulli trial with parameter p equal to the predicted probability of the positive class. Bernoulli Naive Bayes uses Bernoulli distributions to model binary features in text classification.

Binomial Distribution

The binomial distribution generalizes the Bernoulli distribution to multiple trials. It describes the number of successes in n independent Bernoulli trials, each with success probability p. The probability mass function is:

where C(n, k) = n! / (k!(n-k)!) is the binomial coefficient, representing the number of ways to choose k successes from n trials.

The mean is E[X] = np and the variance is Var(X) = np(1-p). As n increases and p remains moderate, the binomial distribution approaches the normal distribution, illustrating the central limit theorem in action.

Let’s implement both distributions:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import stats

from math import comb

# Bernoulli Distribution

print("Bernoulli Distribution")

print("=" * 60)

p = 0.7

print(f"Parameter: p = {p}")

print(f"P(X = 0) = {1-p}")

print(f"P(X = 1) = {p}")

print(f"Mean: {p}")

print(f"Variance: {p*(1-p):.4f}")

print()

# Simulate Bernoulli trials

np.random.seed(42)

n_trials = 1000

bernoulli_samples = np.random.binomial(1, p, n_trials)

print(f"Simulated {n_trials} Bernoulli trials:")

print(f"Number of successes: {np.sum(bernoulli_samples)}")

print(f"Empirical probability: {np.mean(bernoulli_samples):.4f}")

print()

# Binomial Distribution

print("Binomial Distribution")

print("=" * 60)

n = 10

p = 0.5

print(f"Parameters: n = {n}, p = {p}")

print(f"Mean: {n*p}")

print(f"Variance: {n*p*(1-p)}")

print()

# Calculate probabilities for each possible outcome

k_values = np.arange(0, n + 1)

probabilities = [comb(n, k) * (p**k) * ((1-p)**(n-k)) for k in k_values]

print("Probability distribution:")

for k, prob in zip(k_values, probabilities):

print(f"P(X = {k:2d}) = {prob:.4f}")

print()

# Visualization

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(14, 10))

# Bernoulli distribution

axes[0, 0].bar([0, 1], [1-p, p], width=0.4, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='skyblue')

axes[0, 0].set_xlabel('Outcome')

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[0, 0].set_title(f'Bernoulli Distribution (p={p})')

axes[0, 0].set_xticks([0, 1])

axes[0, 0].set_xticklabels(['Failure (0)', 'Success (1)'])

axes[0, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3, axis='y')

# Binomial distribution

axes[0, 1].bar(k_values, probabilities, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='lightcoral')

axes[0, 1].set_xlabel('Number of Successes (k)')

axes[0, 1].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[0, 1].set_title(f'Binomial Distribution (n={n}, p={p})')

axes[0, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3, axis='y')

# Different binomial distributions varying p

axes[1, 0].clear()

n = 20

for p_val in [0.2, 0.5, 0.8]:

k_vals = np.arange(0, n + 1)

probs = stats.binom.pmf(k_vals, n, p_val)

axes[1, 0].plot(k_vals, probs, marker='o', linewidth=2, label=f'p={p_val}')

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel('Number of Successes (k)')

axes[1, 0].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[1, 0].set_title(f'Binomial Distributions (n={n}, varying p)')

axes[1, 0].legend()

axes[1, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Binomial approaching normal as n increases

axes[1, 1].clear()

p = 0.5

for n_val in [10, 30, 50]:

k_vals = np.arange(0, n_val + 1)

probs = stats.binom.pmf(k_vals, n_val, p)

axes[1, 1].plot(k_vals, probs, marker='o', linewidth=2, markersize=3, label=f'n={n_val}')

axes[1, 1].set_xlabel('Number of Successes (k)')

axes[1, 1].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[1, 1].set_title('Binomial Approaching Normal (p=0.5, increasing n)')

axes[1, 1].legend()

axes[1, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Real-world example: A/B testing

print("Real-World Application: A/B Testing")

print("=" * 60)

n_visitors = 1000

conversion_rate_A = 0.10

conversion_rate_B = 0.12

conversions_A = np.random.binomial(n_visitors, conversion_rate_A)

conversions_B = np.random.binomial(n_visitors, conversion_rate_B)

print(f"Website A: {conversions_A} conversions out of {n_visitors} visitors")

print(f"Observed rate: {conversions_A/n_visitors:.4f}")

print(f"Website B: {conversions_B} conversions out of {n_visitors} visitors")

print(f"Observed rate: {conversions_B/n_visitors:.4f}")

print(f"Difference: {(conversions_B - conversions_A)/n_visitors:.4f}")These discrete distributions form the foundation for modeling binary and count data, which appears frequently in classification problems, A/B testing, and categorical data analysis.

The Poisson Distribution: Modeling Rare Events

The Poisson distribution models the number of events occurring in a fixed interval of time or space when events occur independently at a constant average rate. It has one parameter λ (lambda), which represents both the mean and variance of the distribution.

The probability mass function is:

where k is the number of events, e is Euler’s number (approximately 2.71828), and k! is the factorial of k.

The Poisson distribution applies when counting rare events: the number of customers arriving at a store per hour, the number of typos per page in a book, the number of server requests per second, or the number of earthquakes per year. The key assumptions are that events occur independently and at a constant average rate.

As λ increases, the Poisson distribution becomes more symmetric and eventually approximates a normal distribution. For small λ, the distribution is highly right-skewed with most probability concentrated at small values.

Here’s a comprehensive implementation:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import stats

import math

# Poisson Distribution basics

print("Poisson Distribution")

print("=" * 60)

lambda_val = 3.5

print(f"Parameter: λ = {lambda_val}")

print(f"Mean: {lambda_val}")

print(f"Variance: {lambda_val}")

print(f"Standard Deviation: {np.sqrt(lambda_val):.4f}")

print()

# Calculate probabilities

k_values = np.arange(0, 15)

probabilities = [(lambda_val**k * np.exp(-lambda_val)) / math.factorial(k) for k in k_values]

print("Probability distribution:")

for k, prob in zip(k_values, probabilities):

print(f"P(X = {k:2d}) = {prob:.4f}")

print()

# Generate samples

np.random.seed(42)

samples = np.random.poisson(lambda_val, 10000)

print(f"Generated 10,000 samples:")

print(f"Sample mean: {np.mean(samples):.4f}")

print(f"Sample variance: {np.var(samples, ddof=1):.4f}")

print()

# Visualizations

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(14, 10))

# Single Poisson distribution

axes[0, 0].bar(k_values, probabilities, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='skyblue')

axes[0, 0].set_xlabel('Number of Events (k)')

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[0, 0].set_title(f'Poisson Distribution (λ={lambda_val})')

axes[0, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3, axis='y')

# Multiple Poisson distributions

for lam in [1, 3, 5, 10]:

k = np.arange(0, 25)

pmf = stats.poisson.pmf(k, lam)

axes[0, 1].plot(k, pmf, marker='o', linewidth=2, label=f'λ={lam}')

axes[0, 1].set_xlabel('Number of Events (k)')

axes[0, 1].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[0, 1].set_title('Poisson Distributions with Different λ')

axes[0, 1].legend()

axes[0, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Histogram of samples vs theoretical

axes[1, 0].hist(samples, bins=range(0, max(samples)+2), density=True,

alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='lightgreen', label='Sample data')

k_plot = np.arange(0, max(samples)+1)

pmf_plot = stats.poisson.pmf(k_plot, lambda_val)

axes[1, 0].plot(k_plot, pmf_plot, 'ro-', linewidth=2, markersize=6, label='Theoretical PMF')

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel('Number of Events (k)')

axes[1, 0].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[1, 0].set_title('Sample Distribution vs Theoretical')

axes[1, 0].legend()

axes[1, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Poisson approaching normal for large λ

lambda_large = 30

k_large = np.arange(0, 60)

poisson_large = stats.poisson.pmf(k_large, lambda_large)

normal_approx = stats.norm.pdf(k_large, lambda_large, np.sqrt(lambda_large))

axes[1, 1].bar(k_large, poisson_large, alpha=0.6, edgecolor='black',

color='skyblue', label='Poisson')

axes[1, 1].plot(k_large, normal_approx, 'r-', linewidth=2, label='Normal Approximation')

axes[1, 1].set_xlabel('Number of Events (k)')

axes[1, 1].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[1, 1].set_title(f'Poisson (λ={lambda_large}) Approaching Normal')

axes[1, 1].legend()

axes[1, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Real-world application: Website traffic modeling

print("Real-World Application: Website Traffic")

print("=" * 60)

# Simulate hourly visitors for 24 hours

average_visitors_per_hour = 25

hourly_visitors = np.random.poisson(average_visitors_per_hour, 24)

print(f"Average visitors per hour: {average_visitors_per_hour}")

print(f"Total visitors in 24 hours: {np.sum(hourly_visitors)}")

print(f"Mean visitors per hour (observed): {np.mean(hourly_visitors):.2f}")

print(f"Max visitors in any hour: {np.max(hourly_visitors)}")

print(f"Min visitors in any hour: {np.min(hourly_visitors)}")

print()

# Calculate probability of specific events

prob_more_than_30 = 1 - stats.poisson.cdf(30, average_visitors_per_hour)

prob_less_than_20 = stats.poisson.cdf(19, average_visitors_per_hour)

prob_exactly_25 = stats.poisson.pmf(25, average_visitors_per_hour)

print("Event probabilities:")

print(f"P(X > 30): {prob_more_than_30:.4f}")

print(f"P(X < 20): {prob_less_than_20:.4f}")

print(f"P(X = 25): {prob_exactly_25:.4f}")

# Visualize the simulated traffic

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

hours = range(24)

plt.bar(hours, hourly_visitors, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='coral')

plt.axhline(y=average_visitors_per_hour, color='red', linestyle='--',

linewidth=2, label=f'Expected (λ={average_visitors_per_hour})')

plt.xlabel('Hour of Day')

plt.ylabel('Number of Visitors')

plt.title('Simulated Hourly Website Traffic (Poisson Distribution)')

plt.xticks(hours)

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3, axis='y')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()The Poisson distribution is particularly valuable in machine learning for modeling count data, rare events, and arrival processes. It appears in text analysis for modeling word counts, in anomaly detection for identifying unusual event frequencies, and in time series analysis for modeling discrete event occurrences.

The Exponential Distribution: Time Between Events

While the Poisson distribution counts events in an interval, the exponential distribution models the time between events in a Poisson process. If events occur at an average rate of λ per unit time, the time until the next event follows an exponential distribution with parameter λ.

The probability density function is:

The mean is 1/λ and the variance is 1/λ². The exponential distribution is memoryless, meaning that the probability of an event occurring in the next time interval is independent of how much time has already passed. This property makes it useful for modeling lifetimes and waiting times.

The cumulative distribution function, which gives the probability that the event occurs before time t, is:

Let’s explore this distribution:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import stats

# Exponential Distribution basics

print("Exponential Distribution")

print("=" * 60)

lambda_val = 0.5 # Average 0.5 events per unit time

mean_time = 1 / lambda_val

variance_time = 1 / (lambda_val ** 2)

print(f"Parameter: λ = {lambda_val}")

print(f"Mean time between events: {mean_time}")

print(f"Variance: {variance_time}")

print(f"Standard deviation: {np.sqrt(variance_time):.4f}")

print()

# Generate samples

np.random.seed(42)

samples = np.random.exponential(scale=mean_time, size=10000)

print(f"Generated 10,000 samples:")

print(f"Sample mean: {np.mean(samples):.4f}")

print(f"Sample variance: {np.var(samples, ddof=1):.4f}")

print()

# Visualizations

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(14, 10))

# PDF for different λ values

x = np.linspace(0, 10, 1000)

for lam in [0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0]:

pdf = lam * np.exp(-lam * x)

axes[0, 0].plot(x, pdf, linewidth=2, label=f'λ={lam}')

axes[0, 0].set_xlabel('Time')

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Probability Density')

axes[0, 0].set_title('Exponential Distributions with Different λ')

axes[0, 0].legend()

axes[0, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# CDF for different λ values

for lam in [0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0]:

cdf = 1 - np.exp(-lam * x)

axes[0, 1].plot(x, cdf, linewidth=2, label=f'λ={lam}')

axes[0, 1].set_xlabel('Time')

axes[0, 1].set_ylabel('Cumulative Probability')

axes[0, 1].set_title('Cumulative Distribution Functions')

axes[0, 1].legend()

axes[0, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Histogram of samples vs theoretical

axes[1, 0].hist(samples, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.7,

edgecolor='black', color='lightgreen', label='Sample data')

x_plot = np.linspace(0, max(samples), 100)

pdf_plot = stats.expon.pdf(x_plot, scale=mean_time)

axes[1, 0].plot(x_plot, pdf_plot, 'r-', linewidth=2, label='Theoretical PDF')

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel('Time')

axes[1, 0].set_ylabel('Density')

axes[1, 0].set_title(f'Sample Distribution vs Theoretical (λ={lambda_val})')

axes[1, 0].legend()

axes[1, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Demonstrating memoryless property

axes[1, 1].clear()

# P(X > s + t | X > s) = P(X > t) for all s, t > 0

s = 2.0

t_values = np.linspace(0, 5, 100)

conditional_prob = np.exp(-lambda_val * t_values) # Should equal unconditional probability

unconditional_prob = np.exp(-lambda_val * t_values)

axes[1, 1].plot(t_values, conditional_prob, linewidth=2,

label=f'P(X > t+{s} | X > {s})')

axes[1, 1].plot(t_values, unconditional_prob, linewidth=2,

linestyle='--', label='P(X > t)')

axes[1, 1].set_xlabel('Time (t)')

axes[1, 1].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[1, 1].set_title('Memoryless Property of Exponential Distribution')

axes[1, 1].legend()

axes[1, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Real-world application: Customer service wait times

print("Real-World Application: Customer Service Wait Times")

print("=" * 60)

# Average service rate: 4 customers per hour

service_rate = 4.0 # customers per hour

avg_wait_time = 60 / service_rate # minutes

print(f"Service rate: {service_rate} customers per hour")

print(f"Average wait time: {avg_wait_time} minutes")

print()

# Simulate wait times for 100 customers

wait_times = np.random.exponential(scale=avg_wait_time, size=100)

print(f"Simulated 100 customers:")

print(f"Mean wait time: {np.mean(wait_times):.2f} minutes")

print(f"Median wait time: {np.median(wait_times):.2f} minutes")

print(f"Max wait time: {np.max(wait_times):.2f} minutes")

print()

# Calculate probabilities

prob_wait_less_10 = stats.expon.cdf(10, scale=avg_wait_time)

prob_wait_more_20 = 1 - stats.expon.cdf(20, scale=avg_wait_time)

prob_wait_between_5_15 = (stats.expon.cdf(15, scale=avg_wait_time) -

stats.expon.cdf(5, scale=avg_wait_time))

print("Wait time probabilities:")

print(f"P(wait < 10 min): {prob_wait_less_10:.4f} ({prob_wait_less_10*100:.1f}%)")

print(f"P(wait > 20 min): {prob_wait_more_20:.4f} ({prob_wait_more_20*100:.1f}%)")

print(f"P(5 min < wait < 15 min): {prob_wait_between_5_15:.4f} ({prob_wait_between_5_15*100:.1f}%)")

# Visualize simulated wait times

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

plt.hist(wait_times, bins=20, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black', color='coral', density=True)

x_plot = np.linspace(0, max(wait_times), 100)

pdf_plot = stats.expon.pdf(x_plot, scale=avg_wait_time)

plt.plot(x_plot, pdf_plot, 'b-', linewidth=2, label='Theoretical Distribution')

plt.axvline(avg_wait_time, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2,

label=f'Mean: {avg_wait_time:.1f} min')

plt.xlabel('Wait Time (minutes)')

plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.title('Customer Service Wait Time Distribution')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()The exponential distribution is widely used in machine learning for modeling survival times, system lifetimes, and inter-arrival times in queuing systems. Its memoryless property makes it particularly useful for Markov chains and certain types of stochastic processes.

The Uniform Distribution: Equal Probability

The uniform distribution assigns equal probability to all values within a specified range. For a continuous uniform distribution on the interval [a, b], every value between a and b has the same probability density.

The probability density function is:

The mean is (a+b)/2 and the variance is (b-a)²/12. The uniform distribution represents maximum uncertainty within a bounded range, as no value is more likely than any other.

The discrete uniform distribution assigns equal probability to each of a finite set of outcomes, like rolling a fair die where each of the six outcomes has probability 1/6.

Let’s implement both versions:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import stats

# Continuous Uniform Distribution

print("Continuous Uniform Distribution")

print("=" * 60)

a, b = 2, 8

mean = (a + b) / 2

variance = ((b - a) ** 2) / 12

print(f"Parameters: a={a}, b={b}")

print(f"Mean: {mean}")

print(f"Variance: {variance:.4f}")

print(f"Standard deviation: {np.sqrt(variance):.4f}")

print()

# Generate samples

np.random.seed(42)

samples = np.random.uniform(a, b, 10000)

print(f"Generated 10,000 samples:")

print(f"Sample mean: {np.mean(samples):.4f}")

print(f"Sample variance: {np.var(samples, ddof=1):.4f}")

print()

# Discrete Uniform Distribution

print("Discrete Uniform Distribution (Die Roll)")

print("=" * 60)

outcomes = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

prob = 1/6

print(f"Outcomes: {outcomes}")

print(f"Probability for each outcome: {prob:.4f}")

print(f"Mean: {np.mean(outcomes)}")

print()

# Visualizations

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(14, 10))

# Continuous uniform PDF

x = np.linspace(0, 10, 1000)

pdf = stats.uniform.pdf(x, a, b-a)

axes[0, 0].plot(x, pdf, 'b-', linewidth=2)

axes[0, 0].fill_between(x, pdf, where=(x>=a) & (x<=b), alpha=0.3, color='skyblue')

axes[0, 0].set_xlabel('Value')

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Probability Density')

axes[0, 0].set_title(f'Continuous Uniform PDF [a={a}, b={b}]')

axes[0, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

axes[0, 0].axvline(mean, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2, label=f'Mean={mean}')

axes[0, 0].legend()

# Continuous uniform CDF

cdf = stats.uniform.cdf(x, a, b-a)

axes[0, 1].plot(x, cdf, 'b-', linewidth=2)

axes[0, 1].set_xlabel('Value')

axes[0, 1].set_ylabel('Cumulative Probability')

axes[0, 1].set_title(f'Continuous Uniform CDF [a={a}, b={b}]')

axes[0, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Histogram of continuous samples

axes[1, 0].hist(samples, bins=30, density=True, alpha=0.7,

edgecolor='black', color='lightgreen', label='Sample data')

axes[1, 0].axhline(y=1/(b-a), color='red', linestyle='--',

linewidth=2, label='Theoretical density')

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel('Value')

axes[1, 0].set_ylabel('Density')

axes[1, 0].set_title('Sample Distribution vs Theoretical')

axes[1, 0].legend()

axes[1, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Discrete uniform (die roll)

dice_samples = np.random.randint(1, 7, 10000)

unique, counts = np.unique(dice_samples, return_counts=True)

axes[1, 1].bar(unique, counts/len(dice_samples), alpha=0.7,

edgecolor='black', color='coral', label='Sample frequencies')

axes[1, 1].axhline(y=1/6, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2,

label='Theoretical probability')

axes[1, 1].set_xlabel('Die Face')

axes[1, 1].set_ylabel('Probability')

axes[1, 1].set_title('Discrete Uniform Distribution (10,000 Die Rolls)')

axes[1, 1].set_xticks(outcomes)

axes[1, 1].legend()

axes[1, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3, axis='y')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Application in machine learning: Random initialization

print("ML Application: Random Weight Initialization")

print("=" * 60)

# Neural network weight initialization using uniform distribution

n_inputs = 10

n_neurons = 5

# Xavier/Glorot uniform initialization

limit = np.sqrt(6 / (n_inputs + n_neurons))

weights = np.random.uniform(-limit, limit, (n_inputs, n_neurons))

print(f"Weight matrix shape: {weights.shape}")

print(f"Initialization range: [{-limit:.4f}, {limit:.4f}]")

print(f"Weight mean: {np.mean(weights):.6f}")

print(f"Weight std: {np.std(weights, ddof=1):.4f}")

print()

# Visualize weight distribution

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

plt.hist(weights.flatten(), bins=30, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black',

color='skyblue', density=True)

x_plot = np.linspace(weights.min(), weights.max(), 100)

pdf_plot = stats.uniform.pdf(x_plot, -limit, 2*limit)

plt.plot(x_plot, pdf_plot, 'r-', linewidth=2, label='Theoretical PDF')

plt.xlabel('Weight Value')

plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.title('Neural Network Weight Initialization (Xavier/Glorot Uniform)')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Application: Random sampling

print("Application: Random Sampling for Train-Test Split")

print("=" * 60)

n_samples = 1000

test_fraction = 0.2

# Generate random indices uniformly

indices = np.arange(n_samples)

np.random.shuffle(indices)

split_point = int(n_samples * (1 - test_fraction))

train_indices = indices[:split_point]

test_indices = indices[split_point:]

print(f"Total samples: {n_samples}")

print(f"Training samples: {len(train_indices)} ({len(train_indices)/n_samples*100:.1f}%)")

print(f"Test samples: {len(test_indices)} ({len(test_indices)/n_samples*100:.1f}%)")The uniform distribution is fundamental in machine learning for random initialization, data shuffling, and generating random samples. It represents maximum uncertainty and serves as a default choice when no prior information about the distribution is available.

The Beta Distribution: Modeling Probabilities

The beta distribution is a continuous distribution defined on the interval [0, 1], making it perfect for modeling probabilities, proportions, and percentages. It has two shape parameters, α (alpha) and β (beta), that control its shape.

The probability density function is:

where B(α, β) is the beta function, which acts as a normalizing constant. The mean is α/(α+β) and the variance is (αβ)/((α+β)²(α+β+1)).

The beta distribution is extremely flexible. Different values of α and β produce vastly different shapes, from uniform to highly skewed to U-shaped distributions. This flexibility makes it useful for Bayesian inference, where it often serves as a conjugate prior for binomial proportions.

Here’s a comprehensive implementation:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import stats

# Beta Distribution with various parameter combinations

print("Beta Distribution")

print("=" * 60)

param_combinations = [

(1, 1, 'Uniform'),

(2, 2, 'Symmetric bell'),

(5, 2, 'Right-skewed'),

(2, 5, 'Left-skewed'),

(0.5, 0.5, 'U-shaped'),

]

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 3, figsize=(15, 10))

axes = axes.ravel()

x = np.linspace(0, 1, 1000)

for idx, (alpha, beta, description) in enumerate(param_combinations):

pdf = stats.beta.pdf(x, alpha, beta)

mean = alpha / (alpha + beta)

variance = (alpha * beta) / ((alpha + beta)**2 * (alpha + beta + 1))

axes[idx].plot(x, pdf, linewidth=2, color='steelblue')

axes[idx].fill_between(x, pdf, alpha=0.3, color='skyblue')

axes[idx].axvline(mean, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2,

label=f'Mean={mean:.3f}')

axes[idx].set_xlabel('Value')

axes[idx].set_ylabel('Probability Density')

axes[idx].set_title(f'Beta(α={alpha}, β={beta})\n{description}')

axes[idx].legend()

axes[idx].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

axes[idx].set_xlim(0, 1)

print(f"Beta(α={alpha}, β={beta}) - {description}:")

print(f" Mean: {mean:.4f}")

print(f" Variance: {variance:.4f}")

print()

# Remove extra subplot

fig.delaxes(axes[5])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Application in Bayesian inference: Click-through rate estimation

print("Bayesian Application: Click-Through Rate Estimation")

print("=" * 60)

# Prior: uniform distribution (Beta(1, 1))

prior_alpha = 1

prior_beta = 1

# Observed data: 30 clicks out of 100 impressions

clicks = 30

impressions = 100

non_clicks = impressions - clicks

# Posterior: Beta(α + clicks, β + non_clicks)

posterior_alpha = prior_alpha + clicks

posterior_beta = prior_beta + non_clicks

print(f"Prior: Beta({prior_alpha}, {prior_beta}) - Uniform")

print(f"Data: {clicks} clicks, {non_clicks} non-clicks")

print(f"Posterior: Beta({posterior_alpha}, {posterior_beta})")

print()

# Calculate statistics

prior_mean = prior_alpha / (prior_alpha + prior_beta)

posterior_mean = posterior_alpha / (posterior_alpha + posterior_beta)

posterior_std = np.sqrt((posterior_alpha * posterior_beta) /

((posterior_alpha + posterior_beta)**2 * (posterior_alpha + posterior_beta + 1)))

print(f"Prior mean (before seeing data): {prior_mean:.4f}")

print(f"Posterior mean (after seeing data): {posterior_mean:.4f}")

print(f"Posterior std: {posterior_std:.4f}")

print(f"95% Credible interval: [{posterior_mean - 1.96*posterior_std:.4f}, "

f"{posterior_mean + 1.96*posterior_std:.4f}]")

print()

# Visualize prior and posterior

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

x_plot = np.linspace(0, 1, 1000)

prior_pdf = stats.beta.pdf(x_plot, prior_alpha, prior_beta)

posterior_pdf = stats.beta.pdf(x_plot, posterior_alpha, posterior_beta)

plt.plot(x_plot, prior_pdf, linewidth=2, label='Prior', linestyle='--')

plt.plot(x_plot, posterior_pdf, linewidth=2, label='Posterior')

plt.axvline(posterior_mean, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2,

label=f'Posterior Mean={posterior_mean:.3f}')

plt.fill_between(x_plot, posterior_pdf, alpha=0.3)

plt.xlabel('Click-Through Rate')

plt.ylabel('Probability Density')

plt.title('Bayesian Update: Prior to Posterior')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Sequential updating with more data

print("Sequential Bayesian Updates")

print("=" * 60)

# Start with uniform prior

alpha = 1

beta = 1

batches = [

(10, 40), # 10 clicks, 40 impressions

(20, 80), # 20 clicks, 80 impressions

(30, 120), # 30 clicks, 120 impressions

]

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

x_plot = np.linspace(0, 1, 1000)

# Plot initial prior

pdf = stats.beta.pdf(x_plot, alpha, beta)

plt.plot(x_plot, pdf, linewidth=2, label=f'Initial: Beta({alpha}, {beta})', linestyle='--')

for idx, (new_clicks, new_impressions) in enumerate(batches, 1):

# Update parameters

alpha += new_clicks

beta += (new_impressions - new_clicks)

# Plot updated distribution

pdf = stats.beta.pdf(x_plot, alpha, beta)

mean = alpha / (alpha + beta)

plt.plot(x_plot, pdf, linewidth=2, label=f'After batch {idx}: Beta({alpha}, {beta}), mean={mean:.3f}')

plt.xlabel('Click-Through Rate')

plt.ylabel('Probability Density')

plt.title('Sequential Bayesian Updates with Increasing Data')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

total_clicks = sum(c for c, _ in batches)

total_impressions = sum(i for _, i in batches)

print(f"Total data: {total_clicks} clicks out of {total_impressions} impressions")

print(f"Final estimate: {alpha/(alpha+beta):.4f}")

print(f"Frequentist estimate: {total_clicks/total_impressions:.4f}")The beta distribution is particularly important in Bayesian machine learning for modeling uncertainties about probabilities and proportions. It’s the conjugate prior for the binomial distribution, meaning that if you start with a beta prior and observe binomial data, your posterior is also beta, making calculations tractable.

Conclusion: Choosing and Applying Distributions in Machine Learning

Understanding probability distributions is essential for effective machine learning practice. Each distribution has distinct characteristics that make it suitable for different types of data and problems. The normal distribution describes continuous data with symmetric variation around a mean, appearing in measurement errors, natural phenomena, and as a limiting distribution through the central limit theorem. The binomial and Bernoulli distributions model binary outcomes and count discrete successes in fixed trials. The Poisson distribution describes rare events occurring at a constant average rate. The exponential distribution models waiting times between events. The uniform distribution represents maximum uncertainty within bounds. The beta distribution models probabilities and proportions.

Recognizing which distribution fits your data guides important decisions throughout the machine learning pipeline. During exploratory data analysis, identifying the distribution helps you understand your data’s characteristics and detect anomalies. For preprocessing, knowing the distribution informs transformation choices—log transforms for right-skewed data, standardization for normal data. In feature engineering, understanding distributions helps you create meaningful derived features. For model selection, some algorithms assume specific distributions—linear regression assumes normal residuals, naive Bayes with continuous features often assumes Gaussian distributions.

Many machine learning algorithms are fundamentally probabilistic, making distribution knowledge critical. Generative models explicitly model the distribution of features for each class. Bayesian methods require specifying prior distributions and updating them with data. Neural networks often use specific distributions for weight initialization to ensure stable training. Reinforcement learning uses distributions over actions in policy gradient methods.

Beyond theoretical importance, practical skills matter. Learn to visualize distributions using histograms and density plots. Use Q-Q plots to check if data follows a particular distribution. Apply statistical tests like the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality or the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for general distribution fitting. Master Python libraries like scipy.stats and numpy.random for working with distributions efficiently.

As you continue your machine learning journey, distributions will appear repeatedly. When you encounter a new algorithm or technique, ask yourself what distributional assumptions it makes. When you analyze data, consider what distribution best describes it. When you debug model performance, check if violations of distributional assumptions might be the cause. This distributional thinking, combined with solid implementation skills, will make you a more effective machine learning practitioner.