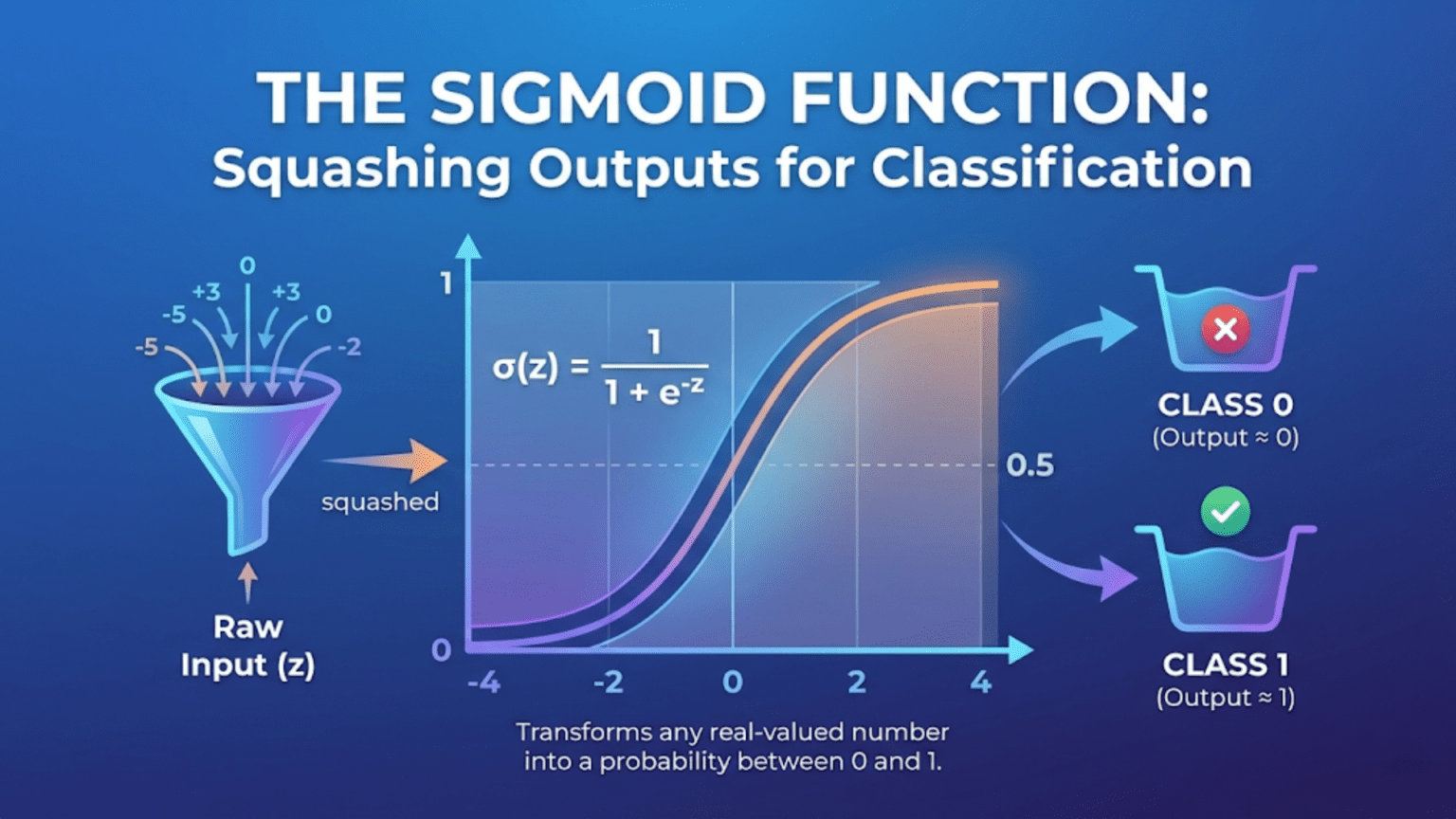

The sigmoid function σ(z) = 1 / (1 + e^(−z)) is a mathematical function that maps any real number to a value between 0 and 1, making it ideal for converting raw model scores into probabilities. Its S-shaped curve smoothly transitions from near-0 for very negative inputs to near-1 for very positive inputs, crossing exactly 0.5 at z=0. In machine learning, sigmoid is used as the output activation in binary classification (logistic regression and neural networks), and its derivative σ'(z) = σ(z)(1 − σ(z)) makes backpropagation computationally elegant. Understanding sigmoid deeply means understanding why logistic regression produces valid probabilities and how neural network classification works.

Introduction: The Function That Turns Scores Into Probabilities

Imagine a judge scoring contestants in a competition. The raw scores might range from −50 to +200, but you need to turn them into probabilities of winning — numbers between 0 and 1. Simply dividing by 200 doesn’t work if scores go negative. Clipping to [0,1] creates discontinuities. What you need is a smooth, principled transformation that maps the entire real number line to the interval (0, 1).

That transformation is the sigmoid function. Given any real number — positive, negative, large, small — sigmoid returns a number strictly between 0 and 1. The function increases monotonically from near-0 to near-1, creating the characteristic S-shaped curve that gives it its name (sigma is the Greek letter S). At the input value of exactly 0, it returns exactly 0.5 — perfect uncertainty between two classes.

Sigmoid is everywhere in machine learning. It is the output activation of logistic regression, the gate mechanism in LSTM cells, an optional activation in neural network hidden layers, the foundation of the binary cross-entropy loss function, and the function whose properties you must understand to reason about vanishing gradients. It connects probability theory, information theory, and neural computation in a single elegant formula.

This comprehensive guide explores the sigmoid function from every angle. You’ll learn the formula and its derivation, every important mathematical property, geometric intuition, the derivative and why it matters for learning, numerical stability considerations, comparison with related functions (tanh, softmax, ReLU), real-world applications, and complete Python implementations with rich visualizations.

The Formula and Its Components

The Definition

σ(z) = 1 / (1 + e^(−z))

Where:

z = any real number (−∞ to +∞)

e = Euler's number ≈ 2.71828

σ = lowercase sigma (Greek letter S)

σ(z) ∈ (0, 1) — strictly between 0 and 1Breaking Down the Formula

Each part of the formula has a role:

The exponential e^(−z):

z = −6: e^(−(−6)) = e^6 ≈ 403.4 (large positive)

z = 0: e^(−0) = e^0 = 1.0 (exactly 1)

z = +6: e^(−6) ≈ 0.002 (near zero)

As z → −∞: e^(−z) → +∞

As z → +∞: e^(−z) → 0Adding 1: (1 + e^(−z)):

z = −6: 1 + 403.4 = 404.4 (large)

z = 0: 1 + 1.0 = 2.0 (exactly 2)

z = +6: 1 + 0.002 = 1.002 (just above 1)Taking the reciprocal: 1 / (1 + e^(−z)):

z = −6: 1 / 404.4 ≈ 0.0025 (near 0)

z = 0: 1 / 2.0 = 0.5000 (exactly 0.5)

z = +6: 1 / 1.002 ≈ 0.9975 (near 1)

Result always in (0, 1) — a valid probability!Why It’s Called “Sigmoid”

Sigma (σ) is the 18th letter of the Greek alphabet, which resembles an S. The function’s graph is S-shaped, giving it the name. The logistic function (another name for sigmoid) was first described by Pierre-François Verhulst in 1838 to model population growth — populations grow slowly, then rapidly, then level off as resources run out. This S-curve appears throughout nature and mathematics.

Mathematical Properties

Property 1: Range Is Strictly (0, 1)

For all z ∈ (−∞, +∞):

0 < σ(z) < 1

σ(z) never equals exactly 0 or 1:

As z → −∞: σ(z) → 0 (approaches but never reaches)

As z → +∞: σ(z) → 1 (approaches but never reaches)

This makes σ(z) a valid probability for any finite input.Property 2: σ(0) = 0.5 — Perfect Uncertainty

σ(0) = 1 / (1 + e^0) = 1 / (1 + 1) = 1/2 = 0.5

Interpretation:

When z = 0, the model has no preference between classes.

P(class 1) = P(class 0) = 0.5 — maximum uncertainty.

The decision boundary in logistic regression is exactly z = 0,

i.e., where σ(z) = 0.5.Property 3: Symmetry Around (0, 0.5)

1 − σ(z) = σ(−z)

Proof:

1 − σ(z) = 1 − 1/(1+e^(−z))

= e^(−z) / (1+e^(−z))

= 1 / (1+e^z)

= σ(−z) ✓

Implication:

σ(3) = 1 − σ(−3)

σ(5) = 1 − σ(−5)

"Confidence of class 1 at z" equals "Confidence of class 0 at −z"

P(class 1 | z) = P(class 0 | −z)Property 4: Monotonically Increasing

If z₁ < z₂, then σ(z₁) < σ(z₂)

Consequence:

Larger z → higher probability

The ranking of examples by z equals

the ranking by σ(z) — crucial for ROC-AUC calculations

ROC-AUC computed on z (raw scores) equals

ROC-AUC computed on σ(z) (probabilities)Property 5: The Elegant Derivative

The sigmoid derivative is one of the most beautiful in mathematics:

dσ/dz = σ(z) × (1 − σ(z))

Proof:

σ(z) = (1 + e^(−z))^(−1)

dσ/dz = −(1 + e^(−z))^(−2) × (−e^(−z))

= e^(−z) / (1 + e^(−z))²

= [1/(1+e^(−z))] × [e^(−z)/(1+e^(−z))]

= σ(z) × [1 − 1/(1+e^(−z))]

= σ(z) × (1 − σ(z)) ✓

Beauty: The derivative is expressed entirely in terms of σ(z) itself.

Once you've computed σ(z) during the forward pass,

the derivative is free — just multiply σ(z) × (1 − σ(z)).Derivative values:

z = −6: σ'(−6) = 0.0025 × 0.9975 ≈ 0.0025 (nearly flat)

z = −3: σ'(−3) = 0.0474 × 0.9526 ≈ 0.045 (shallow)

z = 0: σ'(0) = 0.5 × 0.5 = 0.25 (maximum slope)

z = +3: σ'(3) = 0.9526 × 0.0474 ≈ 0.045 (shallow)

z = +6: σ'(6) = 0.9975 × 0.0025 ≈ 0.0025 (nearly flat)

Maximum derivative at z=0: σ'(0) = 0.25

The sigmoid is steepest at its midpoint.Property 6: Saturation in Tails

For |z| >> 0, σ(z) approaches 0 or 1 very slowly:

σ(3) = 0.9526 (0.048 from 1)

σ(6) = 0.9975 (0.003 from 1)

σ(10) = 0.9999546 (0.00005 from 1)

In saturated regions, σ'(z) ≈ 0.

Gradients vanish → backpropagation fails to update early layers.

This is the vanishing gradient problem for deep networks.

(Why ReLU replaced sigmoid in hidden layers)Complete Python Implementation and Visualization

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.gridspec import GridSpec

# ── Core sigmoid functions ─────────────────────────────────────

def sigmoid(z):

"""Standard sigmoid — may overflow for large negative z."""

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(-z))

def sigmoid_stable(z):

"""

Numerically stable sigmoid using two-branch computation.

Avoids overflow in exp(-z) for very negative z,

and overflow in exp(z) for very positive z.

"""

return np.where(

z >= 0,

1 / (1 + np.exp(-z)), # Safe for z >= 0

np.exp(z) / (1 + np.exp(z)) # Safe for z < 0

)

def sigmoid_derivative(z):

"""dσ/dz = σ(z)(1 − σ(z))."""

s = sigmoid_stable(z)

return s * (1 - s)

def sigmoid_inverse(p):

"""

Logit function — inverse of sigmoid.

Maps probability p ∈ (0,1) back to real number z.

logit(p) = log(p / (1−p))

"""

p = np.clip(p, 1e-15, 1 - 1e-15)

return np.log(p / (1 - p))

# ── Key values table ───────────────────────────────────────────

z_vals = np.array([-6, -4, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 4, 6])

print("┌───────┬──────────┬──────────┐")

print("│ z │ σ(z) │ σ'(z) │")

print("├───────┼──────────┼──────────┤")

for z in z_vals:

s = sigmoid_stable(z)

ds = sigmoid_derivative(z)

print(f"│ {z:+5.1f} │ {s:.6f} │ {ds:.6f} │")

print("└───────┴──────────┴──────────┘")Output:

┌───────┬──────────┬──────────┐

│ z │ σ(z) │ σ'(z) │

├───────┼──────────┼──────────┤

│ -6.0 │ 0.002473│ 0.002467│

│ -4.0 │ 0.017986│ 0.017663│

│ -2.0 │ 0.119203│ 0.104994│

│ -1.0 │ 0.268941│ 0.196612│

│ +0.0 │ 0.500000│ 0.250000│

│ +1.0 │ 0.731059│ 0.196612│

│ +2.0 │ 0.880797│ 0.104994│

│ +4.0 │ 0.982014│ 0.017663│

│ +6.0 │ 0.997527│ 0.002467│

└───────┴──────────┴──────────┘Comprehensive Visualization

z = np.linspace(-8, 8, 500)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(16, 10))

gs = GridSpec(2, 3, figure=fig, hspace=0.4, wspace=0.35)

# ── Panel 1: Sigmoid curve ────────────────────────────────────

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 0])

ax1.plot(z, sigmoid_stable(z), 'steelblue', linewidth=2.5)

ax1.axhline(0.5, color='gray', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7,

linewidth=1, label='σ(0) = 0.5')

ax1.axhline(0.0, color='lightgray', linestyle='-', alpha=0.5, linewidth=0.8)

ax1.axhline(1.0, color='lightgray', linestyle='-', alpha=0.5, linewidth=0.8)

ax1.axvline(0.0, color='gray', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7, linewidth=1)

ax1.scatter([0], [0.5], color='red', s=60, zorder=5)

ax1.set_title('σ(z) = 1/(1+e⁻ᶻ)', fontsize=11)

ax1.set_xlabel('z')

ax1.set_ylabel('σ(z)')

ax1.set_ylim(-0.05, 1.05)

ax1.legend(fontsize=9)

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax1.annotate('σ(0)=0.5\n(decision\nboundary)',

xy=(0, 0.5), xytext=(2, 0.3),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->', color='red'),

fontsize=8, color='red')

# ── Panel 2: Derivative ────────────────────────────────────────

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 1])

ax2.plot(z, sigmoid_derivative(z), 'coral', linewidth=2.5,

label="σ'(z) = σ(z)(1−σ(z))")

ax2.scatter([0], [0.25], color='red', s=60, zorder=5,

label='Max at z=0: σ\'(0)=0.25')

ax2.set_title("Sigmoid Derivative σ'(z)", fontsize=11)

ax2.set_xlabel('z')

ax2.set_ylabel("σ'(z)")

ax2.legend(fontsize=9)

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax2.fill_between(z, sigmoid_derivative(z), alpha=0.2, color='coral')

# ── Panel 3: Symmetry property ────────────────────────────────

ax3 = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 2])

s_pos = sigmoid_stable(z[z >= 0])

s_neg = 1 - sigmoid_stable(-z[z >= 0])

ax3.plot(z[z >= 0], s_pos, 'steelblue', linewidth=2.5, label='σ(z)')

ax3.plot(z[z >= 0], s_neg, 'coral', linewidth=2.5,

linestyle='--', label='1−σ(−z)')

ax3.set_title('Symmetry: σ(z) = 1 − σ(−z)', fontsize=11)

ax3.set_xlabel('z ≥ 0')

ax3.set_ylabel('Value')

ax3.legend(fontsize=9)

ax3.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# ── Panel 4: Saturation zones ─────────────────────────────────

ax4 = fig.add_subplot(gs[1, 0])

s = sigmoid_stable(z)

ds = sigmoid_derivative(z)

ax4.plot(z, s, 'steelblue', linewidth=2, label='σ(z)')

ax4.plot(z, ds, 'coral', linewidth=1.5, label="σ'(z)")

ax4.fill_between(z, ds, alpha=0.3, color='coral')

ax4.fill_between(z[z < -4], s[z < -4], alpha=0.15, color='gray',

label='Saturation zones\n(vanishing gradient)')

ax4.fill_between(z[z > 4], s[z > 4], alpha=0.15, color='gray')

ax4.axvspan(-8, -4, alpha=0.07, color='red')

ax4.axvspan(4, 8, alpha=0.07, color='red')

ax4.set_title('Saturation Zones\n(gradient ≈ 0)', fontsize=11)

ax4.set_xlabel('z')

ax4.legend(fontsize=8)

ax4.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# ── Panel 5: Logit (inverse sigmoid) ─────────────────────────

ax5 = fig.add_subplot(gs[1, 1])

p = np.linspace(0.001, 0.999, 500)

ax5.plot(p, sigmoid_inverse(p), 'seagreen', linewidth=2.5)

ax5.axhline(0, color='gray', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

ax5.axvline(0.5, color='gray', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7,

label='logit(0.5) = 0')

ax5.scatter([0.5], [0.0], color='red', s=60, zorder=5)

ax5.set_title('Logit(p) = σ⁻¹(p) = log(p/(1−p))', fontsize=11)

ax5.set_xlabel('Probability p')

ax5.set_ylabel('z = logit(p)')

ax5.set_ylim(-6, 6)

ax5.legend(fontsize=9)

ax5.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# ── Panel 6: Comparing activation functions ───────────────────

ax6 = fig.add_subplot(gs[1, 2])

relu = np.maximum(0, z)

tanh = np.tanh(z)

ax6.plot(z, sigmoid_stable(z), 'steelblue', lw=2, label='Sigmoid σ(z)')

ax6.plot(z, tanh, 'coral', lw=2, label='Tanh(z)')

ax6.plot(z, relu/6, 'seagreen', lw=2, label='ReLU(z)/6')

ax6.axhline(0, color='gray', linewidth=0.8)

ax6.set_title('Sigmoid vs. Tanh vs. ReLU\n(ReLU scaled for visibility)',

fontsize=10)

ax6.set_xlabel('z')

ax6.set_ylabel('Activation')

ax6.legend(fontsize=9)

ax6.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.suptitle('The Sigmoid Function: Complete Visual Reference',

fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

plt.show()The Logit Function: Sigmoid’s Inverse

Definition

logit(p) = σ⁻¹(p) = log(p / (1−p))

The logit maps probabilities back to real numbers:

p = 0.01 → logit = log(0.01/0.99) = −4.60

p = 0.25 → logit = log(0.25/0.75) = −1.10

p = 0.50 → logit = log(0.50/0.50) = 0.00

p = 0.75 → logit = log(0.75/0.25) = +1.10

p = 0.99 → logit = log(0.99/0.01) = +4.60Log-Odds Interpretation

logit(p) = log(p / (1−p)) = log(odds)

Odds: p/(1−p) = "How many times more likely is class 1 vs. class 0?"

p = 0.75: odds = 3:1 ("three times more likely")

p = 0.50: odds = 1:1 ("equally likely")

In logistic regression:

logit(P(y=1|x)) = w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + ... + b

Interpretation of w₁:

"Each unit increase in x₁ increases the log-odds by w₁"

"Each unit increase multiplies the odds by e^(w₁)"

Example: w₁ = 0.5 for age in churn prediction

Each additional year of age multiplies churn odds by e^0.5 ≈ 1.65

→ 65% higher odds per year of ageSigmoid in Neural Networks

As Output Layer Activation (Binary Classification)

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class BinaryClassifier(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_dim, hidden_dim):

super().__init__()

self.network = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(input_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.ReLU(), # Hidden: ReLU (not sigmoid!)

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim // 2),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim // 2, 1),

nn.Sigmoid() # Output: Sigmoid for probability

)

def forward(self, x):

return self.network(x).squeeze()

# BCELoss = Binary Cross-Entropy Loss

# Used with sigmoid output

criterion = nn.BCELoss()

# Alternative: BCEWithLogitsLoss (more numerically stable)

# Combines sigmoid + BCE in one numerically stable operation

criterion_stable = nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss()

# → Use this in practice: skip Sigmoid layer, use raw logitsWhy Modern Networks Use BCEWithLogitsLoss

# STANDARD (less stable):

output = sigmoid(raw_logit) # σ(z)

loss = -[y*log(output) + (1-y)*log(1-output)]

# Problem: log(sigmoid(z)) can underflow for large z

# BETTER (numerically stable):

# BCEWithLogitsLoss combines both in one operation:

# loss = max(z, 0) - z*y + log(1 + exp(-|z|))

# Avoids overflow/underflow automatically

# PyTorch example:

model_logits = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(input_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 1)

# NO sigmoid here — output raw logits

)

criterion = nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss()

loss = criterion(logits, y_float) # Applies sigmoid internally, stablyIn LSTM Gates

Sigmoid appears as a gating mechanism in Long Short-Term Memory networks:

LSTM gates use sigmoid for binary-like decisions:

Forget gate: f_t = σ(W_f·[h_{t-1}, x_t] + b_f)

→ Values near 0: "forget this information"

→ Values near 1: "keep this information"

Input gate: i_t = σ(W_i·[h_{t-1}, x_t] + b_i)

→ Controls how much new information to write

Output gate: o_t = σ(W_o·[h_{t-1}, x_t] + b_o)

→ Controls what to expose from memory cell

Sigmoid is perfect for gates: output in (0,1) = how open/closedNumerical Stability: A Critical Practical Concern

The Overflow Problem

# Naive sigmoid can fail:

z_large_neg = -1000.0

naive = 1 / (1 + np.exp(-z_large_neg)) # np.exp(1000) → overflow!

# RuntimeWarning: overflow encountered in exp

# Fix 1: numpy handles large values with inf

import numpy as np

np.exp(1000) # Returns inf

1 / (1 + np.inf) # Returns 0.0 — correct!

# numpy's exp is smart enough to handle this for scalar

# Fix 2: Use scipy.special.expit (production-ready sigmoid)

from scipy.special import expit

safe_sigmoid = expit(np.array([-1000, -6, 0, 6, 1000]))

print(safe_sigmoid)

# [0. 0.00247 0.5 0.99753 1.]

# Fix 3: Two-branch implementation (our sigmoid_stable above)

def sigmoid_stable(z):

return np.where(

z >= 0,

1 / (1 + np.exp(-z)),

np.exp(z) / (1 + np.exp(z))

)The Log-of-Sigmoid Problem

Computing log(σ(z)) directly can underflow:

def log_sigmoid(z):

"""

Numerically stable log(σ(z)).

Uses log-sum-exp trick.

Direct: log(1/(1+e^(−z))) = −log(1+e^(−z))

For large negative z: 1+e^(−z) → ∞, log → ∞ (overflow in exp)

Stable version: −log(1+e^(−z)) = −softplus(−z)

"""

return -np.logaddexp(0, -z) # log(1/(1+e^{-z})) stably

def log_one_minus_sigmoid(z):

"""Numerically stable log(1 − σ(z)) = log(σ(−z))."""

return -np.logaddexp(0, z)

# Test

z_test = np.array([-100, -10, 0, 10, 100])

print("log(σ(z)) comparison:")

for z_val in z_test:

direct = np.log(sigmoid_stable(z_val) + 1e-300)

stable = log_sigmoid(z_val)

print(f" z={z_val:5.0f}: direct={direct:.4f} stable={stable:.4f}")Binary Cross-Entropy: Stable Implementation

def binary_cross_entropy_stable(y_true, z):

"""

Numerically stable BCE from raw logits z (before sigmoid).

Standard: −[y·log(σ(z)) + (1−y)·log(1−σ(z))]

Stable: max(z,0) − z·y + log(1 + e^(−|z|))

This avoids computing σ(z) explicitly,

preventing overflow in exp.

"""

return np.maximum(z, 0) - z * y_true + np.log1p(np.exp(-np.abs(z)))

# Verify equivalence

z_sample = np.array([2.0, -1.5, 0.5, -3.0])

y_sample = np.array([1.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0])

bce_naive = -( y_sample * np.log(sigmoid_stable(z_sample) + 1e-15)

+ (1-y_sample) * np.log(1 - sigmoid_stable(z_sample) + 1e-15))

bce_stable = binary_cross_entropy_stable(y_sample, z_sample)

print("BCE comparison (should be identical):")

print(f" Naive: {bce_naive.round(6)}")

print(f" Stable: {bce_stable.round(6)}")Sigmoid vs. Related Functions

Sigmoid vs. Tanh

Sigmoid: σ(z) = 1/(1+e^(−z)), range (0,1), centered at 0.5

Tanh: tanh(z) = (e^z−e^(−z))/(e^z+e^(−z)), range (−1,1), centered at 0

Relationship: tanh(z) = 2σ(2z) − 1

Properties compared:

Sigmoid: 0 to 1 (useful for probabilities)

Tanh: −1 to 1 (zero-centered — better for hidden layers)

Sigmoid: not zero-centered → can cause zig-zagging gradient updates

Tanh: zero-centered → more stable gradient updates

Both saturate in tails → vanishing gradient problem

Both superseded by ReLU in hidden layers of deep networksz = np.linspace(-6, 6, 400)

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

# Functions

ax1.plot(z, sigmoid_stable(z), 'steelblue', lw=2.5, label='Sigmoid (0,1)')

ax1.plot(z, np.tanh(z), 'coral', lw=2.5, label='Tanh (−1,1)')

ax1.axhline(0, color='gray', linewidth=0.8, linestyle='-')

ax1.set_title('Sigmoid vs. Tanh: Output Range')

ax1.set_xlabel('z')

ax1.legend()

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Derivatives

ax2.plot(z, sigmoid_derivative(z), 'steelblue', lw=2.5,

label="σ'(z) — max 0.25")

ax2.plot(z, 1 - np.tanh(z)**2, 'coral', lw=2.5,

label="tanh'(z) — max 1.0")

ax2.set_title('Sigmoid vs. Tanh: Derivatives')

ax2.set_xlabel('z')

ax2.legend()

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Sigmoid vs. Softmax

Sigmoid: For binary classification (2 classes)

Output: Single probability P(class 1)

P(class 0) = 1 − σ(z) automatically

Softmax: For multi-class classification (K > 2 classes)

softmax(z)_k = exp(z_k) / Σⱼ exp(z_j)

Outputs K probabilities that sum to 1

Relationship:

Softmax with K=2 reduces to sigmoid:

softmax([z, 0])₁ = exp(z)/(exp(z)+1) = σ(z)

Use sigmoid: Binary output (single neuron)

Use softmax: Multi-class output (K neurons)Sigmoid vs. ReLU (for Hidden Layers)

Sigmoid:

Range: (0, 1)

Saturates: Yes — vanishing gradient problem

Not zero-centered: Causes zig-zag gradient updates

Computationally: exp() is expensive

Used in: Output layers (binary), LSTM gates

ReLU:

Range: [0, ∞)

Saturates: Only for z < 0

Not zero-centered: But sparse, helps computation

Computationally: Very cheap (max(0,z))

Used in: Hidden layers of almost all modern networks

Verdict: ReLU for hidden layers, Sigmoid for binary output layersThe Sigmoid in Probability Theory

Connection to the Bernoulli Distribution

The Bernoulli distribution models binary outcomes:

P(y=1) = p

P(y=0) = 1−p

Logistic regression models:

p = P(y=1|x) = σ(wᵀx + b)

This means:

y | x ~ Bernoulli(σ(wᵀx + b))

The sigmoid is the canonical link function for

the Bernoulli distribution in the generalized linear model (GLM) framework.Connection to Information Theory

The binary cross-entropy loss:

H(y, ŷ) = −[y·log(ŷ) + (1−y)·log(1−ŷ)]

Is the cross-entropy between the true distribution (y)

and the predicted distribution (ŷ = σ(z)).

Minimizing cross-entropy = Maximum likelihood estimation

of the Bernoulli distribution parameters.

This gives logistic regression its statistical foundation:

Gradient descent on BCE = MLE for Bernoulli modelPractical Reference: When to Use Sigmoid

Use Sigmoid When:

✓ Binary classification output layer

(Predict probability of one of two classes)

✓ LSTM/GRU gates

(Control information flow: 0=closed, 1=open)

✓ Output layer for multi-label classification

(Multiple independent binary decisions simultaneously)

e.g., "Is image: [cat? dog? bird?]" — each independent

✓ When output must be a valid probability in (0,1)

✓ Attention mechanisms (sometimes)Avoid Sigmoid When:

✗ Hidden layers of deep networks

→ Use ReLU, Leaky ReLU, or GELU instead

→ Sigmoid's vanishing gradient will slow/stop training

✗ Multi-class output (mutually exclusive classes)

→ Use Softmax instead (probabilities must sum to 1)

✗ When computing log(σ(z)) directly

→ Use log-sigmoid stable implementation

✗ When z values are very large/small

→ Ensure numerical stability implementationComparison Table: Sigmoid vs. Related Activation Functions

| Property | Sigmoid | Tanh | ReLU | Softmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | 1/(1+e^(−z)) | (e^z−e^(−z))/(e^z+e^(−z)) | max(0,z) | e^zₖ/Σe^zⱼ |

| Output range | (0, 1) | (−1, 1) | [0, ∞) | (0,1), sums to 1 |

| Zero-centered | No | Yes | No | N/A |

| Saturates | Yes (both tails) | Yes (both tails) | Yes (z<0 only) | No |

| Max derivative | 0.25 at z=0 | 1.0 at z=0 | 1 (constant) | Varies |

| Vanishing gradient | Severe | Moderate | Mild (dead ReLU) | No |

| Computationally | Moderate (exp) | Moderate (exp) | Very cheap | Moderate |

| Use: hidden layers | Avoid | Avoid | Default | No |

| Use: binary output | Standard | No | No | No |

| Use: multi-class | No | No | No | Standard |

| Use: LSTM gates | Standard | Standard | No | No |

Conclusion: Simple Formula, Profound Impact

The sigmoid function is one of the most important functions in all of machine learning. A single formula — 1/(1+e^(−z)) — performs a transformation so useful that it appears at the heart of logistic regression, in every binary classification neural network output layer, in every LSTM gate, and in the foundation of the binary cross-entropy loss.

Its mathematical elegance is real, not incidental:

The range (0,1) makes it a natural probability interpreter — any linear score, no matter how large or small, becomes a valid probability with no additional constraints.

The symmetry σ(z) = 1−σ(−z) ensures that the model treats both classes consistently — the probability of class 1 at score z equals the probability of class 0 at score −z.

The derivative σ'(z) = σ(z)(1−σ(z)) is computationally free once σ(z) is computed in the forward pass, making backpropagation through sigmoid neurons efficient.

The logit inverse connects logistic regression to log-odds, giving coefficients an interpretable meaning in terms of how features affect the relative likelihood of outcomes.

The vanishing gradient in the tails is the function’s primary weakness — the reason ReLU replaced it in hidden layers. Understanding this limitation is just as important as understanding the function’s strengths.

Wherever in machine learning a number needs to become a probability, wherever a gate needs to open or close smoothly, wherever a binary decision needs a continuous differentiable foundation — sigmoid is the answer. That is why, despite being one of the oldest activation functions in the field, it remains irreplaceable at the output of every binary classifier built today.