Cross-validation is a resampling technique that evaluates machine learning models by training and testing on multiple different data splits to obtain more reliable performance estimates. The most common method, k-fold cross-validation, divides data into k subsets (folds), trains on k-1 folds and tests on the remaining fold, repeating k times with different test folds. This produces k performance scores that are averaged for a robust estimate, revealing whether good performance on a single split was luck or genuine model quality.

Introduction: The Problem with Single Splits

Imagine evaluating a student’s knowledge by asking just one question. They might happen to know that specific topic well—or poorly—giving you a misleading impression of their overall understanding. You’d get a much more accurate assessment by asking multiple questions covering different topics and averaging the results.

Machine learning faces exactly this challenge. When you split data into a single train-test set and evaluate once, performance depends partly on luck—which specific examples ended up in which set. You might get fortunate with an easy test set, yielding overly optimistic estimates. Or unlucky with a particularly challenging test set, underestimating your model’s true capability.

This single-split evaluation has high variance. Train the same model on different random splits, and you’ll get different performance scores—sometimes dramatically different. A model might achieve 85% accuracy on one split, 78% on another, and 91% on a third. Which number represents true performance? You simply don’t know.

Cross-validation solves this problem by evaluating models on multiple different splits and averaging the results. Instead of one train-test split giving one performance estimate, you get multiple estimates from multiple splits, producing a more stable, reliable assessment of true model quality.

This comprehensive guide explores cross-validation in depth. You’ll learn why it matters, how different methods work, when to use which approach, how to implement them properly, and common pitfalls to avoid. Whether you’re comparing models, tuning hyperparameters, or seeking rigorous performance estimates, understanding cross-validation is essential for reliable machine learning.

Why Cross-Validation Matters

Cross-validation addresses several critical challenges in model evaluation.

Problem 1: Variance in Performance Estimates

Single Split Example:

Same model, different random splits:

Split 1: 82% accuracy

Split 2: 88% accuracy

Split 3: 79% accuracy

Split 4: 85% accuracy

Split 5: 91% accuracy

Which is the "true" performance?

Range: 79% to 91% (12 percentage points!)High Variance: Single split gives unreliable estimate

Cross-Validation Solution:

5-fold cross-validation:

Fold 1: 82%

Fold 2: 88%

Fold 3: 79%

Fold 4: 85%

Fold 5: 91%

Average: 85%

Standard deviation: 4.5%

Report: 85% ± 4.5%Lower Variance: Averaged estimate more reliable

Problem 2: Inefficient Data Use

Traditional Split:

1000 total examples

700 training (70%)

300 test (30%)

Only 70% of data used for training

Only 30% evaluatedCross-Validation:

5-fold CV uses all 1000 examples:

- Each example used for training in 4 folds

- Each example tested in 1 fold

- 100% data utilizationEspecially valuable with limited data.

Problem 3: Lucky/Unlucky Splits

Lucky Split:

By chance, easy examples in test set

Model achieves 95% accuracy

Overestimates true performance

Deploy model → actual performance is 80%

Disappointing!Unlucky Split:

By chance, hard examples in test set

Model achieves 75% accuracy

Underestimates true performance

Reject good model

Miss opportunity!Cross-Validation: Averages across multiple splits, reducing luck factor

Problem 4: Small Dataset Reliability

Challenge: With only 200 examples:

Traditional 70-30 split:

140 training

60 test

Test set too small for reliable estimate

High variance in test performanceCross-Validation: 10-fold CV:

Each fold: 180 training, 20 test

Average 10 folds → more stable estimate

Better use of limited dataK-Fold Cross-Validation: The Standard Approach

The most widely used cross-validation method.

How K-Fold Works

Process:

- Divide data into K equal folds (typically K=5 or K=10)

- For each fold k = 1 to K:

- Use fold k as test set

- Use remaining K-1 folds as training set

- Train model on training folds

- Evaluate on test fold

- Record performance score

- Average K performance scores

- Report mean and standard deviation

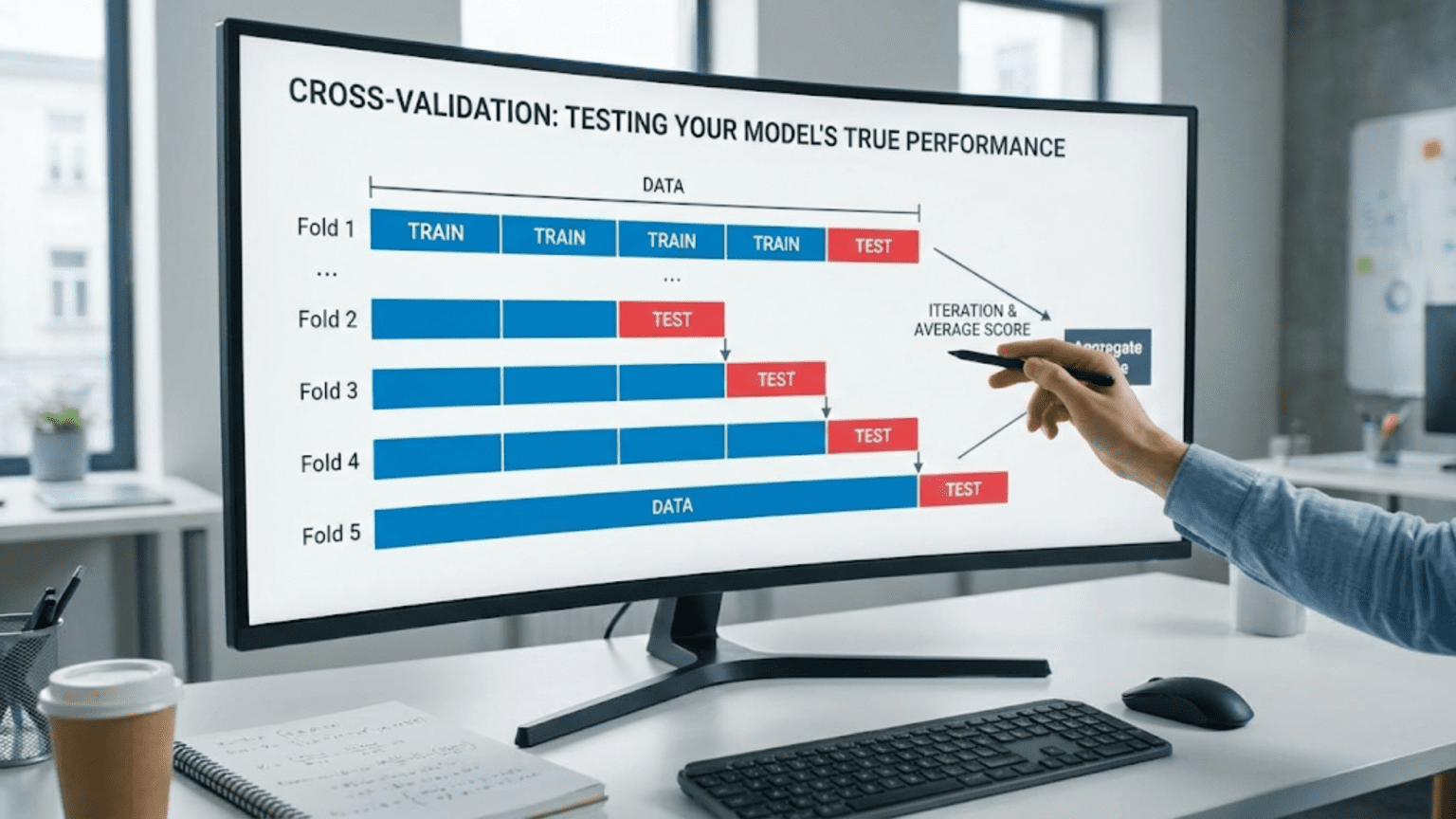

Visual Example (5-Fold):

Iteration 1: [Test][Train][Train][Train][Train] → Score: 82%

Iteration 2: [Train][Test][Train][Train][Train] → Score: 85%

Iteration 3: [Train][Train][Test][Train][Train] → Score: 88%

Iteration 4: [Train][Train][Train][Test][Train] → Score: 84%

Iteration 5: [Train][Train][Train][Train][Test] → Score: 86%

Mean: 85%

Std: 2.3%Implementation Example

Using Scikit-learn:

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

# Initialize model

model = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=100)

# Perform 5-fold CV

scores = cross_val_score(model, X, y, cv=5, scoring='accuracy')

# Results

print(f"Scores: {scores}")

print(f"Mean: {scores.mean():.3f}")

print(f"Std: {scores.std():.3f}")

print(f"95% CI: {scores.mean():.3f} ± {1.96*scores.std():.3f}")Output:

Scores: [0.82, 0.85, 0.88, 0.84, 0.86]

Mean: 0.850

Std: 0.023

95% CI: 0.850 ± 0.045Choosing K

Common Values:

- K=5: Faster, good balance

- K=10: More thorough, standard choice

- K=n (Leave-One-Out): Maximum data use, computationally expensive

Tradeoffs:

Small K (K=3):

- Faster computation (fewer iterations)

- Less data for training each fold

- Higher variance in estimates

- Use when: Computational resources limited

Large K (K=10):

- More computation (more iterations)

- More data for training each fold

- Lower variance in estimates

- Use when: Want reliable estimates

Very Large K (K=20+):

- Expensive computation

- Diminishing returns

- Similar to K=10

- Rarely worth the cost

Recommendation: K=5 or K=10 for most applications

Interpreting Results

Mean Score: Central estimate of model performance

Standard Deviation: Variability across folds

- Small std: Consistent performance

- Large std: Performance varies by data split (concerning)

Example Interpretations:

Model A: 85% ± 2%

- Consistent, reliable

- Performance stable across splits

Model B: 85% ± 12%

- High variance

- Performance depends heavily on data split

- Concerning even with same meanStatistical Significance:

Model A: 85% ± 2%

Model B: 83% ± 2%

Difference: 2 percentage points

Are they significantly different?

Simple test: Check if confidence intervals overlap

A: [81%, 89%]

B: [79%, 87%]

Overlapping → Not clearly different

For rigorous testing: Paired t-test on fold scoresStratified K-Fold: Maintaining Class Distribution

For classification with imbalanced classes.

The Problem with Regular K-Fold

Imbalanced Dataset:

1000 examples: 900 class A, 100 class B (90%-10% split)

Regular 5-fold might create:

Fold 1: 95% A, 5% B

Fold 2: 88% A, 12% B

Fold 3: 92% A, 8% B

Fold 4: 87% A, 13% B

Fold 5: 88% A, 12% B

Each fold has different class distribution!

Unfair comparison, higher varianceStratified Solution

Stratified K-Fold: Each fold maintains overall class distribution

Example:

All folds have:

90% class A

10% class B

Fair comparison across folds

Lower variance in estimatesImplementation:

from sklearn.model_selection import StratifiedKFold

skf = StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=42)

for fold, (train_idx, test_idx) in enumerate(skf.split(X, y)):

X_train, X_test = X[train_idx], X[test_idx]

y_train, y_test = y[train_idx], y[test_idx]

# Check stratification

print(f"Fold {fold+1} - Train class distribution: {np.bincount(y_train)}")

print(f"Fold {fold+1} - Test class distribution: {np.bincount(y_test)}")When to Use:

- Classification problems

- Imbalanced classes

- Want consistent class distribution across folds

Default Choice: Use stratified k-fold for classification unless you have a reason not to

Time Series Cross-Validation: Respecting Temporal Order

For sequential, time-dependent data.

Why Regular CV Fails for Time Series

Problem: Regular k-fold randomly assigns examples to folds

Time Series Issue:

Training on future data to predict past = data leakage!

Example (wrong):

Jan-Mar data in test fold

Apr-Jun data in training folds

Using future to predict past → unrealistic, inflated performanceReal World: Always predict future from past, never vice versa

Time Series Split Approaches

Forward Chaining (Expanding Window)

Method: Progressively expand training set, always test on future

Structure:

Fold 1: Train[1-3], Test[4]

Fold 2: Train[1-4], Test[5]

Fold 3: Train[1-5], Test[6]

Fold 4: Train[1-6], Test[7]

Fold 5: Train[1-7], Test[8]

Training set grows, test always in futureImplementation:

from sklearn.model_selection import TimeSeriesSplit

tscv = TimeSeriesSplit(n_splits=5)

for fold, (train_idx, test_idx) in enumerate(tscv.split(X)):

print(f"Fold {fold+1}")

print(f" Train: indices {train_idx[0]} to {train_idx[-1]}")

print(f" Test: indices {test_idx[0]} to {test_idx[-1]}")When to Use:

- Training data quantity affects performance

- Want to simulate progressive learning

- Standard approach for time series

Sliding Window

Method: Fixed-size training window slides forward

Structure:

Fold 1: Train[1-3], Test[4]

Fold 2: Train[2-4], Test[5]

Fold 3: Train[3-5], Test[6]

Fold 4: Train[4-6], Test[7]

Fold 5: Train[5-7], Test[8]

Training window size constantWhen to Use:

- Recent data more relevant (concept drift)

- Want to evaluate with fixed training size

- Older data becomes less relevant

Implementation Example

Stock Price Prediction:

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.model_selection import TimeSeriesSplit

# Time series data

data = pd.DataFrame({

'date': pd.date_range('2020-01-01', periods=1000, freq='D'),

'price': stock_prices,

'features': feature_data

})

# Sort by time (critical!)

data = data.sort_values('date')

# Time series CV

tscv = TimeSeriesSplit(n_splits=5)

scores = []

for train_idx, test_idx in tscv.split(data):

train = data.iloc[train_idx]

test = data.iloc[test_idx]

# Train model

model.fit(train[features], train['price'])

# Evaluate on future data

score = model.score(test[features], test['price'])

scores.append(score)

print(f"Train: {train['date'].min()} to {train['date'].max()}")

print(f"Test: {test['date'].min()} to {test['date'].max()}")

print(f"Score: {score:.3f}\n")

print(f"Mean Score: {np.mean(scores):.3f}")Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV)

Extreme case where K = n (number of examples).

How LOOCV Works

Process:

- Train on n-1 examples

- Test on 1 example

- Repeat n times (each example as test once)

- Average n scores

Example (10 examples):

Iteration 1: Train[2-10], Test[1]

Iteration 2: Train[1,3-10], Test[2]

Iteration 3: Train[1-2,4-10], Test[3]

...

Iteration 10: Train[1-9], Test[10]Advantages

- Maximum training data: Uses n-1 examples for training

- No randomness: Deterministic (no shuffle needed)

- Unbiased estimate: Each example tested exactly once

Disadvantages

- Computationally expensive: n training runs for n examples

- High variance: Each test set has only 1 example

- Not practical for large datasets

Example Computation:

Dataset with 10,000 examples

LOOCV requires 10,000 training runs!

Compare to:

5-fold CV: 5 training runs

10-fold CV: 10 training runsWhen to Use LOOCV

Good For:

- Very small datasets (n < 100)

- Maximum data efficiency critical

- Computationally cheap models (fast training)

Avoid When:

- Large datasets (too expensive)

- Slow-to-train models

- Need low-variance estimates

Implementation:

from sklearn.model_selection import LeaveOneOut

loo = LeaveOneOut()

scores = []

for train_idx, test_idx in loo.split(X):

model.fit(X[train_idx], y[train_idx])

score = model.score(X[test_idx], y[test_idx])

scores.append(score)

print(f"Mean: {np.mean(scores):.3f}")

print(f"Std: {np.std(scores):.3f}")Nested Cross-Validation: Unbiased Hyperparameter Tuning

For rigorous evaluation when tuning hyperparameters.

The Problem with Standard CV + Hyperparameter Tuning

Typical (Biased) Approach:

1. Use cross-validation to tune hyperparameters

2. Report the best CV score as model performance

Problem: You've "learned" from the CV folds during tuning

The CV score is optimistically biased

True performance on new data will be lowerExample:

Try 100 hyperparameter combinations

Best achieves 87% on 5-fold CV

But: You selected this based on CV performance

Expected performance on truly new data: ~83%

You've overfit to the CV foldsNested CV Solution

Two Loops:

Outer Loop: Generates unbiased performance estimate

- Standard k-fold CV (e.g., 5 folds)

- Each fold treated as “test set”

Inner Loop: Performs hyperparameter tuning

- Nested k-fold CV on training portion (e.g., 3 folds)

- Selects best hyperparameters for that outer fold

Structure:

Outer Fold 1:

Train data: Outer folds 2-5

Inner CV: Tune hyperparameters on folds 2-5

Select best parameters

Test data: Outer fold 1

Evaluate with best parameters → Score 1

Outer Fold 2:

Train data: Outer folds 1, 3-5

Inner CV: Tune hyperparameters

Select best parameters

Test data: Outer fold 2

Evaluate → Score 2

...

Outer Fold 5:

...

Evaluate → Score 5

Final estimate: Average of 5 outer scoresImplementation

Manual Implementation:

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score, GridSearchCV

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

# Outer CV

outer_cv = StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=42)

outer_scores = []

for train_idx, test_idx in outer_cv.split(X, y):

X_train_outer, X_test_outer = X[train_idx], X[test_idx]

y_train_outer, y_test_outer = y[train_idx], y[test_idx]

# Inner CV for hyperparameter tuning

inner_cv = StratifiedKFold(n_splits=3, shuffle=True, random_state=42)

param_grid = {

'n_estimators': [50, 100, 200],

'max_depth': [5, 10, 15]

}

grid_search = GridSearchCV(

RandomForestClassifier(),

param_grid,

cv=inner_cv,

scoring='accuracy'

)

# Tune on outer training fold

grid_search.fit(X_train_outer, y_train_outer)

# Evaluate best model on outer test fold

score = grid_search.score(X_test_outer, y_test_outer)

outer_scores.append(score)

print(f"Best params: {grid_search.best_params_}")

print(f"Outer fold score: {score:.3f}\n")

print(f"Nested CV Score: {np.mean(outer_scores):.3f} ± {np.std(outer_scores):.3f}")Using cross_validate:

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_validate

# GridSearchCV acts as the estimator

grid_search = GridSearchCV(

RandomForestClassifier(),

param_grid={'n_estimators': [50, 100, 200], 'max_depth': [5, 10, 15]},

cv=3 # Inner CV

)

# Outer CV

nested_scores = cross_val_score(

grid_search,

X, y,

cv=5, # Outer CV

scoring='accuracy'

)

print(f"Nested CV: {nested_scores.mean():.3f} ± {nested_scores.std():.3f}")When to Use Nested CV

Essential For:

- Rigorous performance estimates

- Academic publications

- Critical applications (medical, financial)

- When hyperparameter tuning is involved

- Comparing fundamentally different approaches

Overkill For:

- Quick prototyping

- Computationally expensive (nested CV takes 25-50x longer)

- Clear winners without rigorous testing

Tradeoff: Unbiased estimates vs. computational cost

Group K-Fold: Keeping Related Examples Together

For grouped data where examples aren’t independent.

The Problem

Scenario: Medical data with multiple scans per patient

Regular K-Fold Problem:

Patient A has 10 scans

Random k-fold might put:

- 7 scans in training

- 3 scans in test

Model learns Patient A's specific characteristics

Inflated performance (recognizing same patient)

Doesn't reflect real-world (new patients)Group K-Fold Solution

Ensure all examples from same group in same fold

Example:

Patients: A, B, C, D, E (each with multiple scans)

Fold 1: Train[B,C,D,E], Test[A] (all scans from A in test)

Fold 2: Train[A,C,D,E], Test[B]

Fold 3: Train[A,B,D,E], Test[C]

Fold 4: Train[A,B,C,E], Test[D]

Fold 5: Train[A,B,C,D], Test[E]

No patient in both training and testImplementation:

from sklearn.model_selection import GroupKFold

# Groups indicate which patient each scan belongs to

groups = [1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, 5, 5]

# Patient 1: scans 0-2

# Patient 2: scans 3-4

# etc.

gkf = GroupKFold(n_splits=5)

for train_idx, test_idx in gkf.split(X, y, groups=groups):

print(f"Train groups: {set(groups[i] for i in train_idx)}")

print(f"Test groups: {set(groups[i] for i in test_idx)}")When to Use

Required For:

- Multiple measurements per patient/customer/sensor

- Time series data for multiple entities

- Hierarchical data (students within schools)

- Any non-independent observations

Examples:

- Medical: Multiple scans/tests per patient

- Finance: Multiple transactions per customer

- IoT: Multiple readings per sensor

- Social: Multiple posts per user

Practical Example: Complete Cross-Validation Workflow

Let’s walk through a complete example.

Problem Setup

Task: Predict customer churn Data: 5,000 customers Features: 25 features (demographics, usage, billing) Label: Binary (churned=1, retained=0) Class Distribution: 20% churned, 80% retained (imbalanced)

Step 1: Initial Evaluation with Simple Split

Baseline:

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

# Simple 80-20 split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42

)

model = RandomForestClassifier()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

score = model.score(X_test, y_test)

print(f"Test Accuracy: {score:.3f}")Result: Test Accuracy: 0.847

Problem: Single split, could be lucky/unlucky

Step 2: 5-Fold Cross-Validation

Better Estimate:

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

scores = cross_val_score(

RandomForestClassifier(),

X, y,

cv=5,

scoring='accuracy'

)

print(f"CV Scores: {scores}")

print(f"Mean: {scores.mean():.3f} ± {scores.std():.3f}")Result:

CV Scores: [0.832, 0.858, 0.841, 0.829, 0.855]

Mean: 0.843 ± 0.012Insight: Average 0.843, consistent across folds (low std)

Step 3: Stratified K-Fold (Account for Imbalance)

Maintain Class Distribution:

from sklearn.model_selection import StratifiedKFold

skf = StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=42)

scores = cross_val_score(

RandomForestClassifier(),

X, y,

cv=skf,

scoring='accuracy'

)

print(f"Stratified CV: {scores.mean():.3f} ± {scores.std():.3f}")Result: Stratified CV: 0.844 ± 0.011

Comparison:

Regular CV: 0.843 ± 0.012

Stratified CV: 0.844 ± 0.011

Similar but stratified slightly more stableStep 4: Multiple Metrics

Don’t Rely on Accuracy Alone:

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_validate

scoring = {

'accuracy': 'accuracy',

'precision': 'precision',

'recall': 'recall',

'f1': 'f1',

'roc_auc': 'roc_auc'

}

results = cross_validate(

RandomForestClassifier(),

X, y,

cv=StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=42),

scoring=scoring,

return_train_score=True

)

for metric in scoring.keys():

test_scores = results[f'test_{metric}']

print(f"{metric}: {test_scores.mean():.3f} ± {test_scores.std():.3f}")Results:

accuracy: 0.844 ± 0.011

precision: 0.791 ± 0.023

recall: 0.712 ± 0.031

f1: 0.749 ± 0.021

roc_auc: 0.892 ± 0.015Insight:

- Good accuracy and AUC

- Moderate precision and recall

- Recall lower (missing some churners)

Step 5: Hyperparameter Tuning with Nested CV

Rigorous Evaluation:

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

# Hyperparameter grid

param_grid = {

'n_estimators': [50, 100, 200],

'max_depth': [5, 10, 15, None],

'min_samples_split': [2, 5, 10]

}

# Inner CV for tuning

inner_cv = StratifiedKFold(n_splits=3, shuffle=True, random_state=42)

grid_search = GridSearchCV(

RandomForestClassifier(),

param_grid,

cv=inner_cv,

scoring='f1'

)

# Outer CV for unbiased estimate

outer_cv = StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=42)

nested_scores = cross_val_score(

grid_search,

X, y,

cv=outer_cv,

scoring='f1'

)

print(f"Nested CV F1: {nested_scores.mean():.3f} ± {nested_scores.std():.3f}")Results:

Nested CV F1: 0.756 ± 0.019Comparison:

Non-nested (biased): 0.749 ± 0.021

Nested CV (unbiased): 0.756 ± 0.019

Nested actually slightly better here

(Sometimes nested is lower due to removing optimistic bias)Step 6: Final Model Training

After CV confirms good performance:

# Train on all available data

grid_search.fit(X, y)

print(f"Best parameters: {grid_search.best_params_}")

print(f"Best CV score: {grid_search.best_score_:.3f}")

# Final model ready for deployment

final_model = grid_search.best_estimator_Results:

Best parameters: {

'n_estimators': 200,

'max_depth': 15,

'min_samples_split': 5

}

Best CV score: 0.758

Expected production performance: ~0.756 (from nested CV)Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Pitfall 1: Data Leakage in Preprocessing

Wrong:

# Normalize entire dataset

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X) # Uses all data!

# Then cross-validate

scores = cross_val_score(model, X_scaled, y, cv=5)

# Biased! Test folds influenced by their own dataRight:

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

# Pipeline ensures preprocessing happens within CV

pipeline = Pipeline([

('scaler', StandardScaler()),

('model', RandomForestClassifier())

])

scores = cross_val_score(pipeline, X, y, cv=5)

# Correct! Each fold preprocessed independentlyPitfall 2: Not Shuffling Data

Problem: Data might be ordered

Example:

First 80% examples: Class A

Last 20% examples: Class B

Without shuffling:

Some folds have only Class A

Some folds have only Class B

Invalid evaluationSolution: Always shuffle (except time series)

kf = KFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=42)Pitfall 3: Different Random States

Problem: Comparing models with different random splits

Wrong:

# Model A

scores_A = cross_val_score(modelA, X, y, cv=5) # Random state varies

# Model B (different splits!)

scores_B = cross_val_score(modelB, X, y, cv=5)

# Unfair comparisonRight:

# Use same CV splitter for both

cv = StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=42)

scores_A = cross_val_score(modelA, X, y, cv=cv)

scores_B = cross_val_score(modelB, X, y, cv=cv)

# Fair comparison, same foldsPitfall 4: Using Test Set Multiple Times

Problem: Evaluating and tuning based on test performance

Wrong:

# Try different models, check test performance each time

for model in models:

test_score = evaluate_on_test_set(model)

if test_score > best_score:

best_model = model

# You've overfit to test set through selectionRight:

# Use CV for model selection

for model in models:

cv_score = cross_val_score(model, X_train, y_train, cv=5).mean()

if cv_score > best_score:

best_model = model

# Only evaluate best model on test set once

final_score = best_model.score(X_test, y_test)Pitfall 5: Ignoring Computational Cost

Problem: Nested CV with expensive models

Example:

Nested CV: 5 outer × 3 inner = 15 folds

Grid search: 100 parameter combinations

Total training runs: 15 × 100 = 1,500

If each takes 10 minutes: 250 hours!Solutions:

- Use smaller inner CV (2-3 folds)

- Random search instead of grid search

- Reduce parameter grid

- Use simpler models

- Sample data for hyperparameter tuning

Pitfall 6: Wrong CV for Time Series

Problem: Using regular k-fold for temporal data

Example:

Stock price prediction with regular k-fold

→ Training on future data

→ Inflated performance estimates

→ Fails in productionSolution: Always use TimeSeriesSplit for temporal data

Advanced Cross-Validation Techniques

Repeated K-Fold

Idea: Run k-fold multiple times with different random states

Process:

5-fold CV repeated 3 times = 15 evaluations

Average all 15 scores

Even more stable estimateImplementation:

from sklearn.model_selection import RepeatedStratifiedKFold

rskf = RepeatedStratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, n_repeats=3, random_state=42)

scores = cross_val_score(model, X, y, cv=rskf)

print(f"15 scores from 3 repeats of 5-fold CV")

print(f"Mean: {scores.mean():.3f} ± {scores.std():.3f}")When to Use:

- Small datasets (need maximum reliability)

- High-stakes decisions

- Small performance differences to detect

Monte Carlo CV (Shuffle-Split)

Idea: Random train-test splits repeated many times

Difference from K-Fold: Splits are random, not exhaustive

Implementation:

from sklearn.model_selection import ShuffleSplit

ss = ShuffleSplit(n_splits=10, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

scores = cross_val_score(model, X, y, cv=ss)Advantages:

- Control train/test sizes independently

- Can repeat many times

- More randomness in estimates

Disadvantages:

- Some examples may never be in test set

- Some examples may be in test set multiple times

- Less efficient than k-fold

Comparison: Cross-Validation Methods

| Method | Best For | Pros | Cons | Computation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Fold | General purpose | Balanced, efficient | Variance in small K | K × training |

| Stratified K-Fold | Imbalanced classification | Maintains distribution | Only for classification | K × training |

| Time Series CV | Temporal data | Respects time order | Can’t shuffle | K × training |

| LOOCV | Small datasets | Maximum data use | High variance, expensive | n × training |

| Group K-Fold | Grouped data | Prevents leakage | Reduced effective samples | K × training |

| Nested CV | Rigorous evaluation + tuning | Unbiased estimates | Very expensive | (K_outer × K_inner × grid_size) × training |

| Repeated K-Fold | Maximum reliability | Most stable estimates | Expensive | (K × repeats) × training |

Best Practices Summary

Always Do

- Use cross-validation for model selection

- Shuffle data (except time series)

- Set random_state for reproducibility

- Use stratified CV for classification

- Use pipelines to prevent data leakage

- Report mean and standard deviation

- Use same CV splits when comparing models

Consider

- Nested CV for rigorous hyperparameter tuning

- Multiple metrics beyond single score

- Repeated CV for critical decisions

- Appropriate CV for data structure (groups, time series)

- Confidence intervals for statistical rigor

Never Do

- Preprocess before splitting (causes leakage)

- Use test set during development

- Compare models on different splits

- Ignore standard deviation (just reporting mean)

- Use regular CV for time series

Conclusion: The Foundation of Reliable Evaluation

Cross-validation transforms model evaluation from a single, potentially misleading number into a robust, reliable estimate of true performance. By training and testing on multiple different data splits, you average out the luck factor inherent in any single split, revealing whether good performance is genuine or just fortunate data sampling.

The key insights about cross-validation:

K-fold cross-validation is the standard approach, providing good balance between computational cost and estimate reliability. Use K=5 or K=10 for most applications.

Stratified k-fold maintains class distributions across folds, essential for imbalanced classification problems.

Time series CV respects temporal ordering, critical for sequential data where using future to predict past would leak information.

Nested cross-validation provides unbiased estimates when hyperparameter tuning is involved, separating model selection from evaluation.

Group k-fold keeps related examples together, preventing data leakage when observations aren’t independent.

Cross-validation isn’t just about getting better numbers—it’s about honest evaluation. A single train-test split might yield 90% accuracy through luck, leading you to deploy a model that actually performs at 80%. Cross-validation reveals the truth, averaging across multiple scenarios to estimate real-world performance.

The computational cost is worth it. Training 5 or 10 times instead of once seems expensive, but it’s far cheaper than deploying an overfit model, discovering it fails in production, and having to rebuild. Cross-validation catches problems during development, when fixing them is easy.

As you build machine learning systems, make cross-validation standard practice. Use it for model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and performance reporting. Report both mean and standard deviation to convey reliability. Use appropriate variants for your data structure. Prevent data leakage through proper pipelines.

Master cross-validation, and you’ve mastered the art of honest model evaluation—building systems whose development performance actually matches production reality, delivering the value you expect rather than disappointing with inflated estimates that never materialize in the real world.