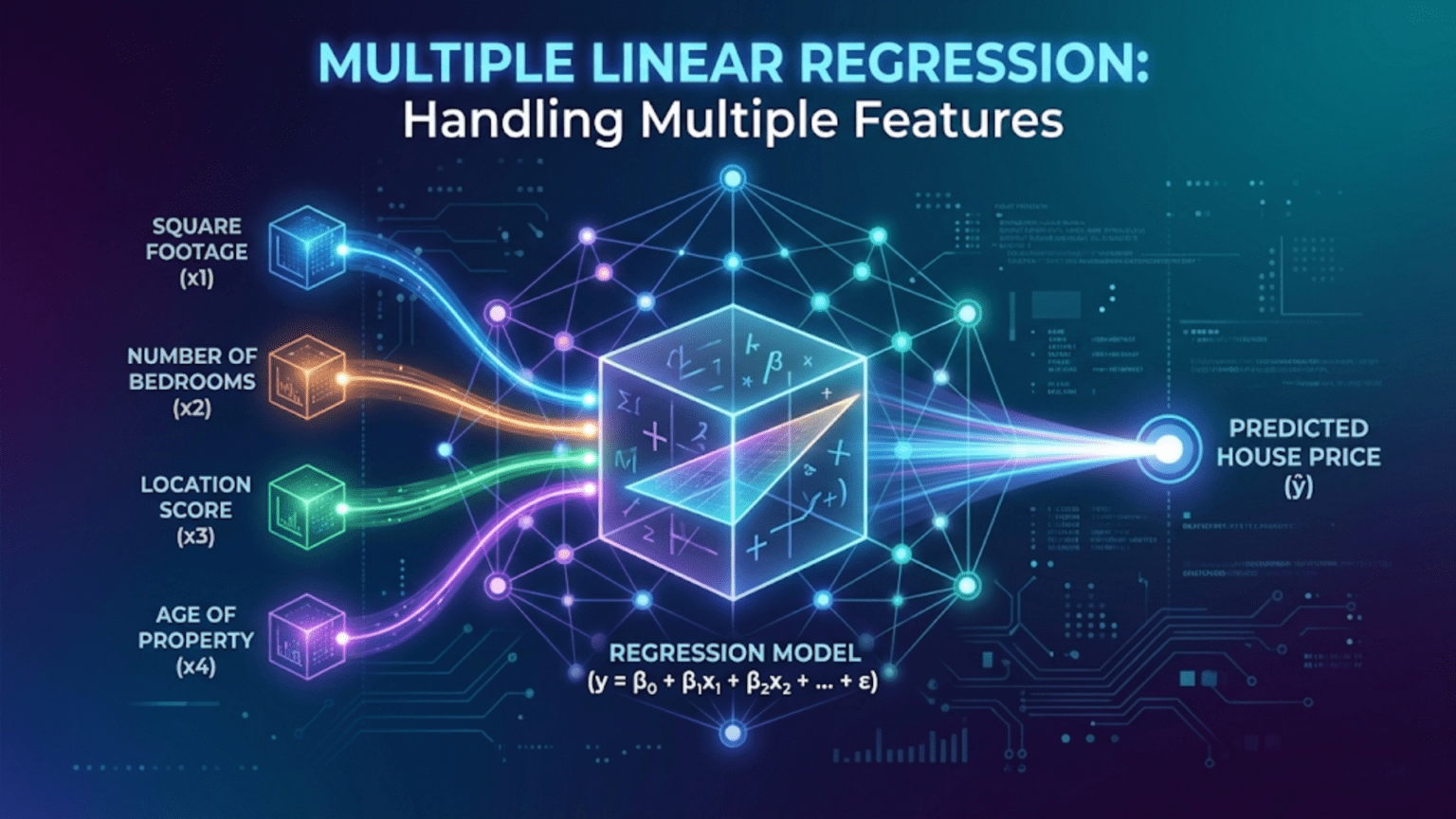

Multiple linear regression extends simple linear regression to predict a continuous output from two or more input features. The model equation becomes ŷ = w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + … + wₙxₙ + b, where each feature xᵢ has its own learned weight wᵢ representing its individual contribution to the prediction. In matrix form this is ŷ = Xw + b, enabling efficient computation over thousands of features and millions of examples simultaneously. Multiple regression is more realistic than simple regression because real-world outcomes almost always depend on more than one factor.

Introduction: One Feature Is Never Enough

Simple linear regression predicts salary from years of experience. But salary depends on much more than experience — it depends on education level, industry, location, company size, and job title. Predicting house prices from square footage alone ignores bedrooms, bathrooms, neighborhood, age, and proximity to schools. Estimating a patient’s blood pressure from only their age misses weight, diet, stress, and medication.

Real-world prediction problems almost universally involve multiple factors. Multiple linear regression handles this reality by extending simple linear regression to accommodate any number of input features. Instead of one weight (slope), the model learns a separate weight for each feature, capturing each variable’s individual contribution to the prediction.

Multiple linear regression is one of the most widely used statistical and machine learning tools in existence. It’s the standard baseline for regression tasks in finance (predicting stock returns), healthcare (modeling clinical outcomes), economics (forecasting GDP components), marketing (predicting customer spending), and engineering (modeling material properties). Understanding it thoroughly unlocks decades of applied statistics literature and provides the clearest conceptual path to neural networks.

This comprehensive guide covers multiple linear regression in complete depth. You’ll learn the model equation and matrix formulation, geometric interpretation, how the algorithm learns multiple weights simultaneously, feature engineering and selection, multicollinearity and other assumptions, model evaluation, regularization as an extension, and complete Python implementations across multiple realistic datasets.

From Simple to Multiple: Extending the Model

Simple Linear Regression (1 Feature)

ŷ = w₁x₁ + b

One feature x₁

One weight w₁ to learn

One bias b to learn

Total parameters: 2Example: Predict salary from years_experience

ŷ = 7,500 × years_experience + 38,000

↑ ↑

weight biasMultiple Linear Regression (n Features)

ŷ = w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + w₃x₃ + ... + wₙxₙ + b

n features x₁, x₂, ..., xₙ

n weights w₁, w₂, ..., wₙ to learn

One bias b to learn

Total parameters: n + 1Example: Predict salary from multiple features

ŷ = 7,500 × years_experience

+ 5,000 × education_level

+ 3,000 × certifications

+ 2,500 × management_role

− 1,200 × commute_hours

+ 42,000

Each feature has its own weight capturing its individual contribution.Matrix Form: Efficient Computation

For a dataset with m examples and n features, matrix notation is essential:

Feature Matrix X (m × n):

x₁ x₂ x₃ ... xₙ

┌───────────────────────────────┐

1 │ x₁⁽¹⁾ x₂⁽¹⁾ x₃⁽¹⁾ ... xₙ⁽¹⁾ │ ← example 1

2 │ x₁⁽²⁾ x₂⁽²⁾ x₃⁽²⁾ ... xₙ⁽²⁾ │ ← example 2

⋮ │ ⋮ ⋮ ⋮ ⋮ │

m │ x₁⁽ᵐ⁾ x₂⁽ᵐ⁾ x₃⁽ᵐ⁾ ... xₙ⁽ᵐ⁾ │ ← example m

└───────────────────────────────┘Weight Vector w (n × 1):

w = [w₁, w₂, w₃, ..., wₙ]ᵀPrediction (entire dataset at once):

ŷ = Xw + b shape: (m, 1)

This single matrix multiplication computes predictions

for ALL m examples simultaneously.The Geometry: Hyperplanes

Simple linear regression fits a line to 2D data. Multiple regression fits a hyperplane.

Two Features → Plane

ŷ = w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + b

With 2 features, the model defines a flat plane in 3D space:

- x₁ axis: Feature 1 (e.g., sqft)

- x₂ axis: Feature 2 (e.g., age)

- ŷ axis: Target (e.g., price)

The plane tilts:

- w₁ controls slope along x₁ axis

- w₂ controls slope along x₂ axis

- b shifts plane up/downVisualisation:

ŷ (price)

│ ╱╱╱╱╱╱╱

│ ╱╱╱╱╱╱╱ ← Fitted plane

│ ╱╱╱╱╱╱╱

│╱╱╱╱╱╱╱

└───────────── x₁ (sqft)

╱

x₂ (age)n Features → Hyperplane

With n features, the model defines an n-dimensional hyperplane:

ŷ = w₁x₁ + w₂x₂ + ... + wₙxₙ + b = 0We can no longer visualise it, but the math remains identical. The plane becomes a hyperplane — a flat surface in high-dimensional space that separates and predicts.

Decision Boundary Intuition

Each weight controls the tilt along one feature dimension:

w₁ = +150: Every extra sq ft → price increases by $150

w₂ = +8000: Every extra bedroom → price increases by $8,000

w₃ = −500: Every extra year of age → price decreases by $500

w₄ = −3000: Every extra mile from center → price decreases by $3,000The model captures each feature’s independent contribution, assuming all other features are held constant (ceteris paribus interpretation).

Learning Multiple Weights: Gradient Descent

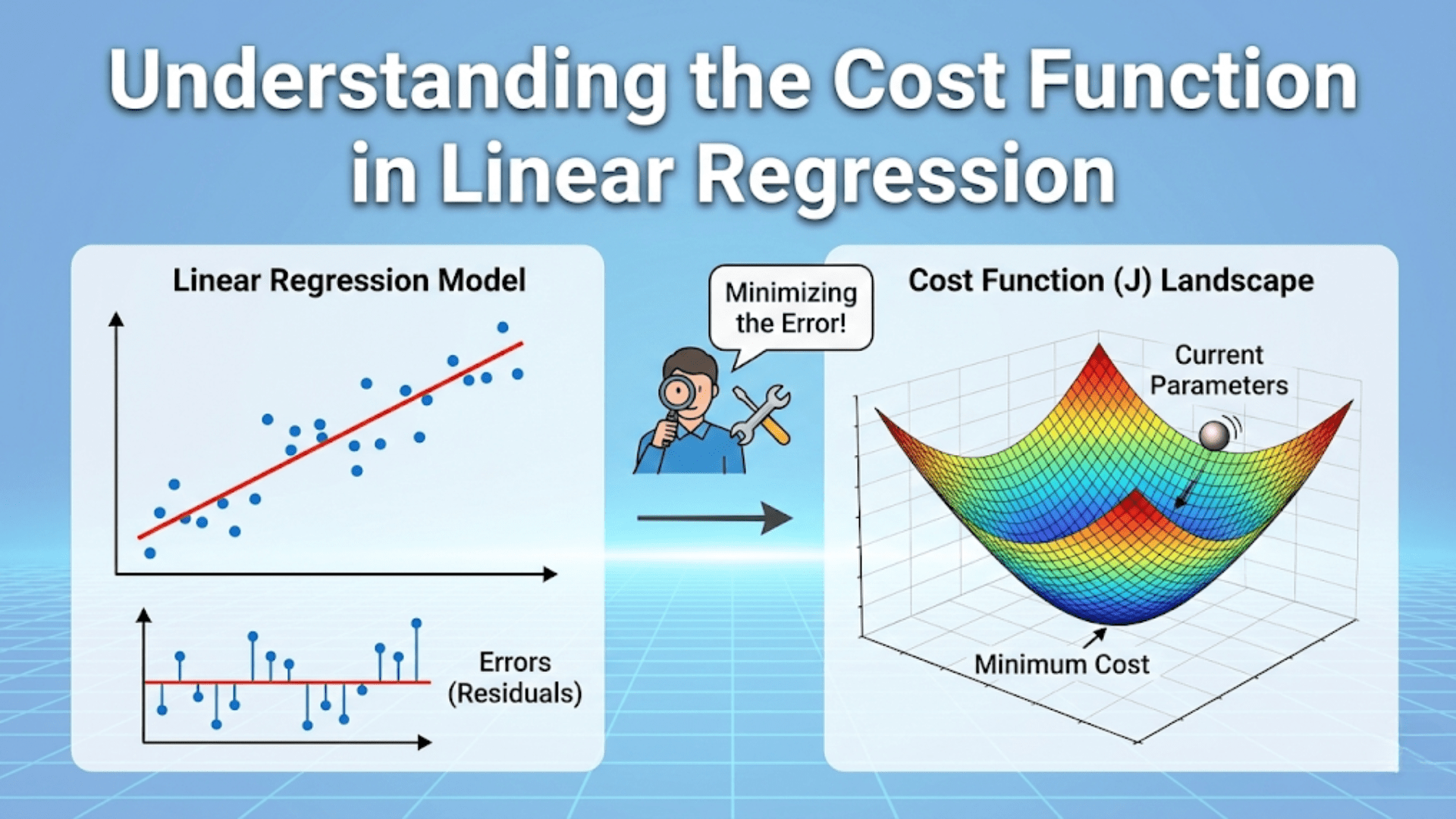

Cost Function (Same MSE, More Parameters)

J(w, b) = (1/2m) × Σᵢ₌₁ᵐ (ŷᵢ − yᵢ)²

= (1/2m) × ||Xw + b − y||²

Identical formula to simple regression — just more weights to optimize.Gradients for All Weights Simultaneously

The gradient with respect to the full weight vector:

∂J/∂w = (1/m) × Xᵀ(ŷ − y) shape: (n, 1)

∂J/∂b = (1/m) × Σᵢ (ŷᵢ − yᵢ) scalarMatrix form computes ALL weight gradients at once:

Xᵀ(ŷ − y) simultaneously computes:

∂J/∂w₁ = (1/m) Σᵢ (ŷᵢ−yᵢ) × x₁ᵢ

∂J/∂w₂ = (1/m) Σᵢ (ŷᵢ−yᵢ) × x₂ᵢ

...

∂J/∂wₙ = (1/m) Σᵢ (ŷᵢ−yᵢ) × xₙᵢ

No loop needed — one matrix multiply handles all n features.Update Rule (Vectorized)

w ← w − α × (1/m) × Xᵀ(Xw + b − y)

b ← b − α × (1/m) × Σᵢ (Xw + b − y)ᵢThis is exactly the same formula as simple regression — the matrix notation absorbs the extra features automatically.

Complete Step-by-Step Example

Dataset: Predicting House Prices

Features (4 inputs):

sqft — total living area (square feet)

bedrooms — number of bedrooms

age — age of house in years

dist_city — distance from city center (miles)Training Data (10 houses):

sqft bed age dist price($k)

1200 2 30 5 210

1500 3 20 3 280

1800 3 10 8 265

2200 4 5 2 380

900 1 45 12 145

2500 4 2 1 450

1600 3 15 6 290

1100 2 35 9 185

2800 5 1 3 520

1350 2 25 7 230Step 1: Set Up Matrices

import numpy as np

X = np.array([

[1200, 2, 30, 5],

[1500, 3, 20, 3],

[1800, 3, 10, 8],

[2200, 4, 5, 2],

[ 900, 1, 45,12],

[2500, 4, 2, 1],

[1600, 3, 15, 6],

[1100, 2, 35, 9],

[2800, 5, 1, 3],

[1350, 2, 25, 7]

], dtype=float)

y = np.array([210, 280, 265, 380, 145,

450, 290, 185, 520, 230], dtype=float)

m, n = X.shape

print(f"Examples: {m}, Features: {n}")

# Examples: 10, Features: 4Step 2: Feature Scaling (Critical!)

# Standardize: subtract mean, divide by std

X_mean = X.mean(axis=0) # Per-feature mean

X_std = X.std(axis=0) # Per-feature std

X_scaled = (X - X_mean) / X_std

print("Feature means:", X_mean.round(1))

print("Feature stds:", X_std.round(1))

# Feature means: [1695. 2.9 18.8 5.6]

# Feature stds: [ 571.9 1.1 14.4 3.4]Why this is critical for multiple regression:

Unscaled features have vastly different ranges:

sqft: 900 – 2800 (range ~1900)

bedrooms: 1 – 5 (range 4)

age: 1 – 45 (range 44)

dist_city: 1 – 12 (range 11)

Without scaling, gradient descent would:

- Take tiny steps for sqft (large scale, huge gradient)

- Take enormous steps for bedrooms (small scale, tiny gradient)

- Converge extremely slowly or fail entirely

After standardization, all features: mean=0, std=1

Gradient descent converges smoothly.Step 3: Manual Gradient Descent (One Iteration)

# Initialize

w = np.zeros(n) # [0, 0, 0, 0]

b = 0.0

alpha = 0.1

# Predictions

y_pred = X_scaled @ w + b # All zeros initially

# Errors

errors = y_pred - y

print("Initial errors:", errors[:3].round(1))

# Initial errors: [-210. -280. -265.]

# Cost

cost = (1/(2*m)) * np.sum(errors**2)

print(f"Initial cost: {cost:.1f}")

# Initial cost: 90275.8

# Gradients

dw = (1/m) * (X_scaled.T @ errors) # shape: (4,)

db = (1/m) * np.sum(errors)

print("Gradients dw:", dw.round(3))

print("Gradient db:", round(db, 3))

# Gradients dw: [-135.8 -12.5 8.1 15.3]

# Gradient db: -295.5

# Update

w = w - alpha * dw

b = b - alpha * db

print("\nAfter 1 iteration:")

print("w:", w.round(4))

print("b:", round(b, 4))

# w: [13.5805 1.2535 -0.8051 -1.5255]

# b: 29.5500Step 4: Full Training Loop

def train_multiple_regression(X, y, alpha=0.1, n_iter=2000):

m, n = X.shape

w = np.zeros(n)

b = 0.0

cost_history = []

for i in range(n_iter):

# Forward pass

y_pred = X @ w + b

errors = y_pred - y

# Cost

cost = (1/(2*m)) * np.sum(errors**2)

cost_history.append(cost)

# Gradients

dw = (1/m) * (X.T @ errors)

db = (1/m) * np.sum(errors)

# Update

w -= alpha * dw

b -= alpha * db

return w, b, cost_history

w_learned, b_learned, history = train_multiple_regression(

X_scaled, y, alpha=0.1, n_iter=2000

)

print("Learned weights:", w_learned.round(4))

print("Learned bias: ", round(b_learned, 4))

print(f"Final cost: {history[-1]:.4f}")

print(f"Initial cost: {history[0]:.4f}")Step 5: Evaluate and Interpret

# Predictions on training set

y_pred_train = X_scaled @ w_learned + b_learned

# R² score

ss_res = np.sum((y - y_pred_train)**2)

ss_tot = np.sum((y - y.mean())**2)

r2 = 1 - ss_res/ss_tot

rmse = np.sqrt(np.mean((y - y_pred_train)**2))

mae = np.mean(np.abs(y - y_pred_train))

print(f"R²: {r2:.4f}")

print(f"RMSE: ${rmse:.1f}k")

print(f"MAE: ${mae:.1f}k")

# Interpret weights (standardized → need to scale back)

feature_names = ['sqft', 'bedrooms', 'age', 'dist_city']

print("\nFeature contributions (per 1 std increase):")

for name, coef in zip(feature_names, w_learned):

direction = "increases" if coef > 0 else "decreases"

print(f" {name:12s}: price {direction} by ${abs(coef):.1f}k")Full Implementation with Scikit-learn

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score, mean_squared_error, mean_absolute_error

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# ── 1. Larger Synthetic Dataset ────────────────────────────────

np.random.seed(42)

m = 1000

sqft = np.random.normal(1800, 500, m).clip(600, 4000)

bedrooms = np.random.choice([1, 2, 3, 4, 5], m,

p=[0.05, 0.25, 0.40, 0.25, 0.05]).astype(float)

age = np.random.uniform(0, 60, m)

dist_city = np.random.uniform(0.5, 25, m)

garage = np.random.choice([0, 1, 2], m,

p=[0.2, 0.5, 0.3]).astype(float)

price = (

130 * sqft

+ 9_000 * bedrooms

- 600 * age

- 2_500 * dist_city

+ 12_000 * garage

+ 30_000

+ np.random.normal(0, 18_000, m)

)

X = np.column_stack([sqft, bedrooms, age, dist_city, garage])

y = price

feature_names = ['sqft', 'bedrooms', 'age', 'dist_city', 'garage']

print(f"Dataset: {m} houses")

print(f"Price range: ${y.min()/1000:.0f}k – ${y.max()/1000:.0f}k")

print(f"Mean price: ${y.mean()/1000:.0f}k")

# ── 2. Split ────────────────────────────────────────────────────

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42

)

# ── 3. Scale ────────────────────────────────────────────────────

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_train_s = scaler.fit_transform(X_train)

X_test_s = scaler.transform(X_test)

# ── 4. Train ────────────────────────────────────────────────────

model = LinearRegression()

model.fit(X_train_s, y_train)

# ── 5. Evaluate ─────────────────────────────────────────────────

y_pred_train = model.predict(X_train_s)

y_pred_test = model.predict(X_test_s)

print(f"\nTraining R²: {r2_score(y_train, y_pred_train):.4f}")

print(f"Test R²: {r2_score(y_test, y_pred_test):.4f}")

print(f"Test RMSE: ${np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred_test))/1000:.1f}k")

print(f"Test MAE: ${mean_absolute_error(y_test, y_pred_test)/1000:.1f}k")

# ── 6. Interpret Coefficients ────────────────────────────────────

print("\n" + "="*55)

print(" Coefficients (per 1 standard deviation change)")

print("="*55)

for name, coef in zip(feature_names, model.coef_):

bar = "█" * int(abs(coef) / 5000)

sign = "+" if coef >= 0 else "−"

print(f" {name:12s} {sign}${abs(coef)/1000:6.1f}k {bar}")

print(f" {'intercept':12s} ${model.intercept_/1000:.1f}k")

# ── 7. Visualise ─────────────────────────────────────────────────

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(16, 5))

# Actual vs Predicted

axes[0].scatter(y_test/1000, y_pred_test/1000,

alpha=0.4, s=20, color='steelblue')

lim = [min(y_test.min(), y_pred_test.min())/1000,

max(y_test.max(), y_pred_test.max())/1000]

axes[0].plot(lim, lim, 'r--', linewidth=1.5)

axes[0].set_xlabel("Actual Price ($k)")

axes[0].set_ylabel("Predicted Price ($k)")

axes[0].set_title("Actual vs Predicted")

axes[0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Residuals vs Predicted

residuals = y_test - y_pred_test

axes[1].scatter(y_pred_test/1000, residuals/1000,

alpha=0.4, s=20, color='coral')

axes[1].axhline(0, color='black', linewidth=1.5, linestyle='--')

axes[1].set_xlabel("Predicted Price ($k)")

axes[1].set_ylabel("Residual ($k)")

axes[1].set_title("Residuals vs Predicted\n(should be random cloud)")

axes[1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Feature Importances (abs coef)

abs_coefs = np.abs(model.coef_)

idx = np.argsort(abs_coefs)[::-1]

axes[2].barh([feature_names[i] for i in idx],

abs_coefs[idx] / 1000,

color='steelblue')

axes[2].set_xlabel("|Coefficient| ($k per std)")

axes[2].set_title("Feature Importance\n(standardized coefficients)")

axes[2].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Interpreting Coefficients Correctly

Coefficient interpretation is one of the most important and commonly misunderstood aspects of multiple regression.

Raw (Unstandardized) Coefficients

When features are NOT scaled:

ŷ = 130 × sqft + 9000 × bedrooms − 600 × age + ...

Interpretation of w₁ = 130:

"Holding all other features constant, each additional

square foot is associated with a $130 increase in price."

This is the ceteris paribus (all else equal) interpretation.

It captures the partial effect of each feature.Standardized Coefficients

When features ARE standardized (mean=0, std=1):

ŷ = 48500 × sqft_std + 7200 × bedrooms_std − 5400 × age_std + ...

Interpretation of w₁ = 48500:

"A one standard deviation increase in sqft is associated

with a $48,500 increase in predicted price."

Standardized coefficients are comparable across features —

they tell you which features have the biggest effect on predictions.Practical Comparison

Standardized coefficients (sorted by importance):

sqft: +$48,500 per std ← Largest effect

bedrooms: +$7,200 per std

garage: +$5,900 per std

age: −$5,400 per std

dist_city: −$4,200 per std ← Smallest effect

This ranking tells you which features matter most for predictions.Causation vs. Correlation Warning

Multiple regression finds associations, not causes.

"Each extra bedroom adds $9,000 to price" means:

In this dataset, houses with more bedrooms tend to be

worth $9,000 more, after controlling for sqft, age, etc.

It does NOT mean:

Adding a bedroom causes a $9,000 price increase.

(Confounders, reverse causality possible)

For causal claims: need experiments or causal inference methods.Key Assumptions and How to Check Them

Multiple regression has assumptions that affect the validity of results.

1. Linearity

Assumption: Relationship between each feature and target is linear (or can be made linear).

How to check:

# Plot each feature against residuals

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, len(feature_names), figsize=(18, 4))

for i, (ax, name) in enumerate(zip(axes, feature_names)):

ax.scatter(X_test[:, i], residuals/1000, alpha=0.3, s=15)

ax.axhline(0, color='red', linestyle='--')

ax.set_xlabel(name)

ax.set_ylabel("Residual ($k)")

ax.set_title(f"{name} vs Residuals")

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Violation signs: Curved pattern in residual plots Fix: Add polynomial features, log-transform, or use non-linear model

2. No Multicollinearity

Assumption: Features are not highly correlated with each other.

Why it matters:

If sqft and rooms_count are correlated (r=0.95):

- Model can't distinguish their individual effects

- Coefficients become unstable, high variance

- Standard errors inflate — significance tests unreliable

Example:

Without multicollinearity: w_sqft = 130 (stable)

With multicollinearity: w_sqft = 400, w_rooms = −270 (unstable pair)

Both predict similarly, but individual coefficients meaninglessHow to check — Correlation Matrix:

df = pd.DataFrame(X_train, columns=feature_names)

corr = df.corr()

plt.figure(figsize=(7, 5))

import seaborn as sns

sns.heatmap(corr, annot=True, fmt='.2f', cmap='RdBu_r',

center=0, vmin=-1, vmax=1)

plt.title("Feature Correlation Matrix")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()How to check — Variance Inflation Factor (VIF):

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

vif_data = pd.DataFrame()

vif_data["feature"] = feature_names

vif_data["VIF"] = [

variance_inflation_factor(X_train_s, i)

for i in range(X_train_s.shape[1])

]

print(vif_data.sort_values("VIF", ascending=False))VIF Interpretation:

VIF < 5: Acceptable — little multicollinearity

VIF 5–10: Moderate — consider removing/combining

VIF > 10: Severe — definite multicollinearity problemFixes:

- Remove one of the correlated features

- Combine them (e.g., bedroom_per_sqft)

- Use Ridge regression (regularization)

- Apply PCA dimensionality reduction

3. Homoscedasticity (Constant Variance)

Assumption: Residual variance is constant across all predicted values.

Check: Residuals vs. Predicted scatter plot should be a random horizontal band.

Violation (heteroscedasticity):

Residuals

│ ↑ Fan shape: variance grows with prediction

│ ╱╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ ╱ ╲╲

│╱──────────── Predicted

Fix: Log-transform the target variable

Use robust regression

Weighted least squares4. Normality of Residuals

Assumption: Residuals are approximately normally distributed (matters for statistical tests).

Check:

from scipy import stats

# Histogram

plt.hist(residuals/1000, bins=30, edgecolor='black')

plt.xlabel("Residual ($k)")

plt.title("Distribution of Residuals")

plt.show()

# Statistical test

stat, p_value = stats.shapiro(residuals[:50]) # Shapiro-Wilk (small sample)

print(f"Shapiro-Wilk p-value: {p_value:.4f}")

# p > 0.05: fail to reject normality (residuals appear normal)5. No Influential Outliers

Assumption: No single point has undue influence on the regression.

Check — Cook’s Distance:

import statsmodels.api as sm

X_sm = sm.add_constant(X_train_s)

ols_model = sm.OLS(y_train, X_sm).fit()

influence = ols_model.get_influence()

cooks_d = influence.cooks_distance[0]

# Flag influential points

threshold = 4 / len(y_train)

influential = np.where(cooks_d > threshold)[0]

print(f"Influential points (Cook's D > {threshold:.4f}): {len(influential)}")Feature Selection: Choosing the Right Features

Not all features improve the model — irrelevant features add noise.

Method 1: Correlation with Target

# Pearson correlation of each feature with target

correlations = pd.DataFrame(X_train, columns=feature_names).corrwith(

pd.Series(y_train)

).abs().sort_values(ascending=False)

print("Feature-Target Correlations:")

print(correlations.round(3))Method 2: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

from sklearn.feature_selection import RFE

rfe = RFE(estimator=LinearRegression(), n_features_to_select=3)

rfe.fit(X_train_s, y_train)

selected = [name for name, support in zip(feature_names, rfe.support_) if support]

print(f"Top 3 features selected by RFE: {selected}")

# Rank all features

ranking = pd.Series(rfe.ranking_, index=feature_names).sort_values()

print("\nFeature rankings (1 = best):")

print(ranking)Method 3: Regularization (Automatic Selection)

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso

# Lasso drives unimportant weights to exactly zero

lasso = Lasso(alpha=1000)

lasso.fit(X_train_s, y_train)

print("Lasso coefficients:")

for name, coef in zip(feature_names, lasso.coef_):

status = "SELECTED" if coef != 0 else "eliminated"

print(f" {name:12s}: {coef:+.1f} ({status})")Regularization: Ridge and Lasso

When features are many or correlated, regularization prevents overfitting.

Ridge Regression (L2)

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

ridge = Ridge(alpha=1000) # alpha = regularization strength

ridge.fit(X_train_s, y_train)

print(f"Ridge R² (test): {ridge.score(X_test_s, y_test):.4f}")

print("Ridge coefficients (shrunk toward zero):")

for name, coef in zip(feature_names, ridge.coef_):

print(f" {name:12s}: {coef/1000:+.2f}k")Ridge: Shrinks all weights toward zero but keeps all features.

Lasso Regression (L1)

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso

lasso = Lasso(alpha=500)

lasso.fit(X_train_s, y_train)

print(f"Lasso R² (test): {lasso.score(X_test_s, y_test):.4f}")

print("Lasso coefficients (sparsified):")

for name, coef in zip(feature_names, lasso.coef_):

status = "" if coef != 0 else " ← eliminated"

print(f" {name:12s}: {coef/1000:+.2f}k{status}")Lasso: Drives some weights to exactly zero — performs feature selection.

Choosing Regularization Strength

from sklearn.linear_model import RidgeCV

# Cross-validated Ridge — automatically selects best alpha

alphas = [0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1000, 10000]

ridge_cv = RidgeCV(alphas=alphas, scoring='r2', cv=5)

ridge_cv.fit(X_train_s, y_train)

print(f"Best alpha: {ridge_cv.alpha_}")

print(f"Test R²: {ridge_cv.score(X_test_s, y_test):.4f}")Making Predictions on New Data

# Predict for 3 new houses

new_houses = np.array([

[2000, 3, 10, 4, 1], # 2000 sqft, 3 bed, 10yr, 4mi, 1 garage

[1200, 2, 30, 8, 0], # 1200 sqft, 2 bed, 30yr, 8mi, 0 garage

[3000, 5, 2, 2, 2], # 3000 sqft, 5 bed, 2yr, 2mi, 2 garage

])

new_names = ["Modern family home", "Older starter home", "Luxury property"]

# Scale using the same scaler fit on training data

new_scaled = scaler.transform(new_houses)

predictions = model.predict(new_scaled)

print("Price Predictions for New Houses:")

print("-" * 45)

for name, pred in zip(new_names, predictions):

print(f" {name:22s}: ${pred/1000:.0f}k")Comparison: Simple vs. Multiple Linear Regression

| Aspect | Simple (1 feature) | Multiple (n features) |

|---|---|---|

| Equation | ŷ = wx + b | ŷ = w₁x₁+…+wₙxₙ+b |

| Matrix form | ŷ = Xw + b (X: m×1) | ŷ = Xw + b (X: m×n) |

| Parameters | 2 (w, b) | n+1 (w₁…wₙ, b) |

| Geometry | Line in 2D | Hyperplane in (n+1)D |

| Cost function | Same MSE | Same MSE |

| Gradient | ∂J/∂w scalar | ∂J/∂w vector (n dims) |

| Feature scaling | Needed for GD | Needed for GD |

| Multicollinearity | N/A | Must check |

| Coefficient meaning | Slope of line | Partial effect |

| Realistic? | Rarely | Almost always |

Conclusion: The Foundation of Predictive Modeling

Multiple linear regression is the realistic version of linear regression. Real-world outcomes never depend on a single variable, and multiple regression lets you capture how many factors jointly determine the target — each with its own estimated weight.

Everything from simple linear regression carries forward unchanged. The same MSE cost function, the same gradient descent, the same R² evaluation, the same assumptions about linearity and constant variance. Matrix notation absorbs the additional complexity elegantly — one equation handles one feature or one thousand features identically.

Several critical lessons emerge from this article:

Feature scaling is non-negotiable for gradient descent with multiple features. Unscaled features create elongated, poorly-conditioned cost landscapes that gradient descent navigates poorly or fails to converge on.

Coefficients have ceteris paribus meaning: each weight captures the partial effect of its feature, holding all others constant. This is powerful for interpretation but requires caution — correlation is not causation.

Multicollinearity undermines coefficient stability. Correlated features can’t have their individual contributions reliably separated. VIF above 10 is a warning sign demanding action.

Regularization extends multiple regression into a practical tool for high-dimensional data. Ridge handles correlated features gracefully; Lasso performs automatic feature selection.

The architecture directly extends to neural networks: multiple linear regression is literally a neural network with zero hidden layers. Each additional layer is another set of the same linear transformations followed by non-linear activations. The gradient calculations, the weight updates, the matrix operations — all identical.

Master multiple linear regression and you’ve mastered the computational pattern at the core of every model in machine learning.