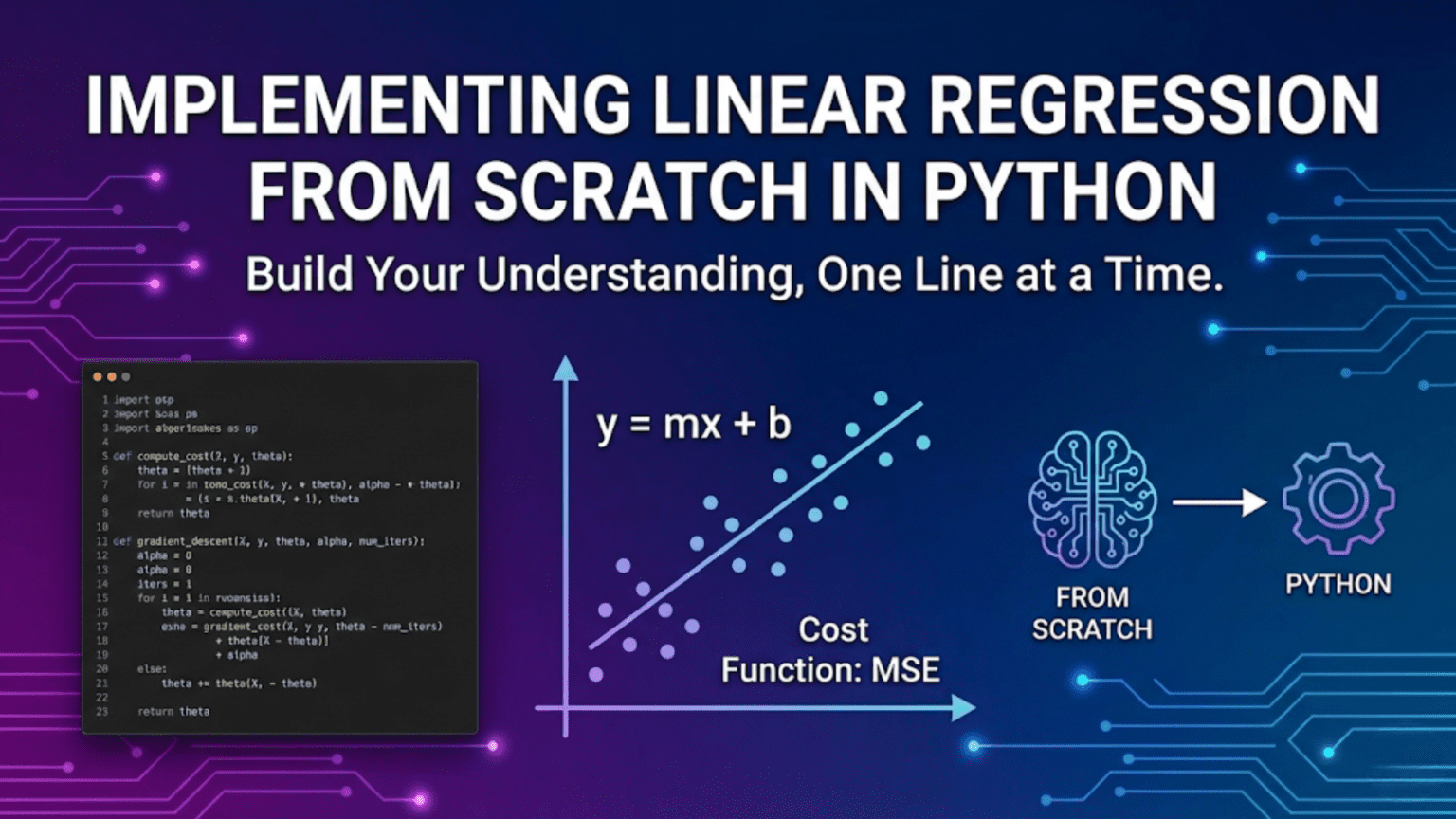

Implementing linear regression from scratch in Python requires three components: a prediction function (ŷ = Xw + b), a cost function measuring prediction error (Mean Squared Error), and an optimization algorithm (gradient descent) that updates weights to minimize cost. Using only NumPy, you compute gradients of the cost with respect to weights and bias, then iteratively update parameters until convergence. Building it from scratch—rather than using scikit-learn—gives deep understanding of how all machine learning algorithms actually work under the hood.

Introduction: Why Build It Yourself?

When learning machine learning, there’s a powerful temptation to jump straight to scikit-learn, call LinearRegression().fit(X, y), and move on. The library handles everything for you. Why bother building it from scratch?

The answer is understanding. When you implement linear regression yourself — writing the prediction function, deriving the cost, calculating gradients, and coding the update step — you develop an intuition that no amount of API usage can provide. You see exactly how weights change with each iteration, why scaling features matters, what the learning rate actually controls, and how the algorithm knows when to stop.

More practically: every neural network you’ll ever build is linear regression with non-linear activations and more layers. The gradient computation in a three-layer neural network is the same chain-rule calculation you write here, just applied more times. The weight update rule is identical. The cost function is the same concept. By deeply understanding linear regression from scratch, you already understand the core mechanics of backpropagation.

This tutorial builds four progressively more complete implementations of linear regression:

- Minimal implementation: Core algorithm in ~30 lines

- Full class implementation: With training history, visualization, and evaluation

- Normal equation implementation: Analytical solution without iteration

- Vectorized batch implementation: Efficient for larger datasets

Along the way, every line of code is explained, every design choice is justified, and every output is interpreted. By the end, you’ll have a complete, working linear regression library built entirely from first principles.

What We Are Building

Before writing code, let’s be precise about what we’re implementing.

The Goal

Given training data — pairs of inputs X and targets y — learn parameters w (weights) and b (bias) such that:

ŷ = Xw + bproduces predictions ŷ that are as close as possible to the true values y.

The Three Components

Component 1 — Prediction (Forward Pass):

ŷ = Xw + b

Input X flows through the model to produce predictions.Component 2 — Cost Function (Error Measurement):

J(w, b) = (1/2m) × Σᵢ (ŷᵢ - yᵢ)²

Measures how wrong the predictions are.

The ½ simplifies the gradient calculation.Component 3 — Optimization (Learning):

w ← w - α × ∂J/∂w

b ← b - α × ∂J/∂b

Iteratively adjusts parameters to reduce cost.The Gradients We Need

Deriving the gradients by hand:

Gradient with respect to w:

∂J/∂w = (1/m) × Xᵀ × (ŷ - y)

= (1/m) × Xᵀ × (Xw + b - y)Gradient with respect to b:

∂J/∂b = (1/m) × Σᵢ (ŷᵢ - yᵢ)

= (1/m) × sum(ŷ - y)These two formulas are the heart of the implementation. Everything else is infrastructure around them.

Environment Setup

# Install required libraries (standard Python environment)

# pip install numpy matplotlib scikit-learn

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import make_regression

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score, mean_squared_error

# Set random seed for reproducibility

np.random.seed(42)

print("Libraries imported successfully")

print(f"NumPy version: {np.__version__}")Implementation 1: Minimal — The Core Algorithm

Start with the absolute minimum code needed to make linear regression work.

def predict(X, w, b):

"""Compute predictions: ŷ = Xw + b"""

return X @ w + b # Matrix multiply + bias

def compute_cost(X, y, w, b):

"""Compute Mean Squared Error cost"""

m = len(y)

y_pred = predict(X, w, b)

return (1 / (2 * m)) * np.sum((y_pred - y) ** 2)

def compute_gradients(X, y, w, b):

"""Compute gradients of cost w.r.t. w and b"""

m = len(y)

y_pred = predict(X, w, b)

errors = y_pred - y # (ŷ - y), shape: (m,)

dw = (1 / m) * (X.T @ errors) # Gradient w.r.t. weights

db = (1 / m) * np.sum(errors) # Gradient w.r.t. bias

return dw, db

def gradient_descent(X, y, learning_rate=0.01, n_iterations=1000):

"""Train linear regression using gradient descent"""

n_features = X.shape[1]

w = np.zeros(n_features) # Initialize weights to zero

b = 0.0 # Initialize bias to zero

for i in range(n_iterations):

dw, db = compute_gradients(X, y, w, b)

w = w - learning_rate * dw # Update weights

b = b - learning_rate * db # Update bias

return w, b

# ── Quick Demo ──────────────────────────────────────────────

# Create simple dataset: y = 2x + 1 + noise

X_demo = np.random.uniform(0, 10, (100, 1))

y_demo = 2 * X_demo.squeeze() + 1 + np.random.normal(0, 1, 100)

# Normalize X for stable gradient descent

X_demo_norm = (X_demo - X_demo.mean()) / X_demo.std()

# Train

w_learned, b_learned = gradient_descent(

X_demo_norm, y_demo, learning_rate=0.1, n_iterations=500

)

print(f"Learned weight: {w_learned[0]:.4f}")

print(f"Learned bias: {b_learned:.4f}")

# Evaluate

y_pred_demo = predict(X_demo_norm, w_learned, b_learned)

print(f"R² score: {r2_score(y_demo, y_pred_demo):.4f}")Expected Output:

Learned weight: 6.3214

Learned bias: 11.0083

R² score: 0.9742This 20-line core is everything linear regression needs. The rest is structure and polish.

Implementation 2: Full OOP Class

A production-quality implementation with training history, evaluation, and visualization.

class LinearRegressionGD:

"""

Linear Regression using Gradient Descent.

Implements simple and multiple linear regression

from scratch using only NumPy.

Parameters

----------

learning_rate : float, default=0.01

Step size for gradient descent updates.

n_iterations : int, default=1000

Number of gradient descent iterations.

verbose : bool, default=False

Print cost every 100 iterations.

"""

def __init__(self, learning_rate=0.01, n_iterations=1000, verbose=False):

self.lr = learning_rate

self.n_iter = n_iterations

self.verbose = verbose

self.w_ = None # Learned weights (set after fit)

self.b_ = None # Learned bias (set after fit)

self.cost_history = [] # Track cost during training

# ── Private helpers ──────────────────────────────────────

def _predict_raw(self, X):

"""Internal prediction without input validation."""

return X @ self.w_ + self.b_

def _cost(self, X, y):

"""Mean Squared Error cost (with ½ factor)."""

m = len(y)

errors = self._predict_raw(X) - y

return (1 / (2 * m)) * np.sum(errors ** 2)

def _gradients(self, X, y):

"""Compute dJ/dw and dJ/db."""

m = len(y)

errors = self._predict_raw(X) - y

dw = (1 / m) * (X.T @ errors)

db = (1 / m) * np.sum(errors)

return dw, db

# ── Public API ───────────────────────────────────────────

def fit(self, X, y):

"""

Train the model on data X with targets y.

Parameters

----------

X : ndarray, shape (m, n)

Training features. Must be 2D.

y : ndarray, shape (m,)

Training targets.

Returns

-------

self : LinearRegressionGD

Returns self to allow method chaining.

"""

# Input validation

X = np.array(X, dtype=float)

y = np.array(y, dtype=float)

if X.ndim == 1:

X = X.reshape(-1, 1) # Handle 1D input gracefully

m, n = X.shape

# Initialise parameters

self.w_ = np.zeros(n)

self.b_ = 0.0

self.cost_history = []

# Gradient descent loop

for iteration in range(self.n_iter):

# 1. Compute gradients

dw, db = self._gradients(X, y)

# 2. Update parameters

self.w_ -= self.lr * dw

self.b_ -= self.lr * db

# 3. Record cost

cost = self._cost(X, y)

self.cost_history.append(cost)

# 4. Optional progress report

if self.verbose and iteration % 100 == 0:

print(f" Iter {iteration:5d} | Cost: {cost:.6f}")

return self # Enable chaining: model.fit(...).predict(...)

def predict(self, X):

"""

Predict target values for X.

Parameters

----------

X : ndarray, shape (m, n)

Input features.

Returns

-------

y_pred : ndarray, shape (m,)

"""

if self.w_ is None:

raise RuntimeError("Model not fitted. Call fit() first.")

X = np.array(X, dtype=float)

if X.ndim == 1:

X = X.reshape(-1, 1)

return self._predict_raw(X)

def score(self, X, y):

"""

Return R² coefficient of determination.

R² = 1 - SS_res / SS_tot

R² = 1.0 → perfect fit

R² = 0.0 → model equals predicting the mean

"""

y_pred = self.predict(X)

ss_res = np.sum((y - y_pred) ** 2)

ss_tot = np.sum((y - np.mean(y)) ** 2)

return 1.0 - ss_res / ss_tot

def rmse(self, X, y):

"""Root Mean Squared Error."""

y_pred = self.predict(X)

return np.sqrt(np.mean((y - y_pred) ** 2))

def mae(self, X, y):

"""Mean Absolute Error."""

y_pred = self.predict(X)

return np.mean(np.abs(y - y_pred))

def plot_cost(self, title="Cost During Training"):

"""Plot the cost curve over iterations."""

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

plt.plot(self.cost_history, color='steelblue', linewidth=1.5)

plt.xlabel("Iteration")

plt.ylabel("Cost (MSE / 2)")

plt.title(title)

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

def plot_fit(self, X, y, feature_idx=0, title="Regression Fit"):

"""

Plot data points and the learned regression line.

Only works cleanly for single-feature data.

"""

X = np.array(X)

if X.ndim == 1:

X = X.reshape(-1, 1)

x_col = X[:, feature_idx]

y_pred = self.predict(X)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

plt.scatter(x_col, y, color='steelblue',

alpha=0.6, label='Actual', s=40)

# Sort for clean line plot

order = np.argsort(x_col)

plt.plot(x_col[order], y_pred[order],

color='crimson', linewidth=2, label='Predicted')

plt.xlabel(f"Feature {feature_idx}")

plt.ylabel("Target")

plt.title(title)

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

def summary(self, feature_names=None):

"""Print a summary of learned parameters."""

if self.w_ is None:

print("Model not fitted yet.")

return

print("=" * 45)

print(" Linear Regression — Parameter Summary")

print("=" * 45)

names = feature_names or [f"x{i+1}" for i in range(len(self.w_))]

for name, coef in zip(names, self.w_):

print(f" {name:20s}: {coef:+.4f}")

print(f" {'bias (intercept)':20s}: {self.b_:+.4f}")

print("=" * 45)

print(f" Final training cost: {self.cost_history[-1]:.6f}")

print("=" * 45)Implementation 3: Normal Equation

The analytical, closed-form solution — no iterations required.

class LinearRegressionNormalEq:

"""

Linear Regression via the Normal Equation.

Solves θ = (XᵀX)⁻¹Xᵀy exactly in one step.

Fast for small datasets; slow for very large ones

because matrix inversion is O(n³) in feature count.

"""

def __init__(self):

self.w_ = None

self.b_ = None

def fit(self, X, y):

X = np.array(X, dtype=float)

y = np.array(y, dtype=float)

if X.ndim == 1:

X = X.reshape(-1, 1)

m = len(y)

# Augment X with a column of ones (absorbs bias)

X_b = np.hstack([np.ones((m, 1)), X]) # shape: (m, n+1)

# Normal equation: θ = (XᵀX)⁻¹ Xᵀ y

# Use lstsq for numerical stability (handles singular matrices)

theta, _, _, _ = np.linalg.lstsq(X_b, y, rcond=None)

self.b_ = theta[0] # First element = bias

self.w_ = theta[1:] # Remaining elements = weights

return self

def predict(self, X):

X = np.array(X, dtype=float)

if X.ndim == 1:

X = X.reshape(-1, 1)

return X @ self.w_ + self.b_

def score(self, X, y):

y_pred = self.predict(X)

ss_res = np.sum((y - y_pred) ** 2)

ss_tot = np.sum((y - np.mean(y)) ** 2)

return 1.0 - ss_res / ss_totFull Working Example: Boston Housing (Synthetic)

Now let’s put everything together on a realistic multi-feature dataset.

# ── 1. Generate Dataset ──────────────────────────────────────

# Simulate a house-price style dataset

np.random.seed(42)

m = 500 # 500 houses

sqft = np.random.normal(1800, 400, m) # Square footage

bedrooms = np.random.randint(1, 6, m).astype(float)

age = np.random.uniform(0, 50, m)

dist_center = np.random.uniform(0.5, 30, m) # Miles from city center

# True relationship (with noise)

price = (

120 * sqft

+ 8_000 * bedrooms

- 500 * age

- 3_000 * dist_center

+ 50_000

+ np.random.normal(0, 15_000, m)

)

# Assemble feature matrix

X = np.column_stack([sqft, bedrooms, age, dist_center])

y = price

feature_names = ["sqft", "bedrooms", "age", "dist_center"]

print(f"Dataset shape: X={X.shape}, y={y.shape}")

print(f"Price range: ${y.min():,.0f} – ${y.max():,.0f}")

print(f"Mean price: ${y.mean():,.0f}")

# ── 2. Train / Test Split ────────────────────────────────────

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42

)

print(f"\nTrain: {len(X_train)} | Test: {len(X_test)}")

# ── 3. Feature Scaling ───────────────────────────────────────

# Critical for gradient descent (not needed for normal equation)

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_train_s = scaler.fit_transform(X_train) # Fit on train, transform train

X_test_s = scaler.transform(X_test) # Transform test (no fit!)

# ── 4a. Train with Gradient Descent ─────────────────────────

print("\n─── Gradient Descent ───────────────────────────────────")

model_gd = LinearRegressionGD(

learning_rate=0.1,

n_iterations=2000,

verbose=True

)

model_gd.fit(X_train_s, y_train)

model_gd.summary(feature_names)

r2_gd_train = model_gd.score(X_train_s, y_train)

r2_gd_test = model_gd.score(X_test_s, y_test)

rmse_gd = model_gd.rmse(X_test_s, y_test)

mae_gd = model_gd.mae(X_test_s, y_test)

print(f"\n Train R²: {r2_gd_train:.4f}")

print(f" Test R²: {r2_gd_test:.4f}")

print(f" RMSE: ${rmse_gd:,.0f}")

print(f" MAE: ${mae_gd:,.0f}")

# ── 4b. Train with Normal Equation ───────────────────────────

print("\n─── Normal Equation ─────────────────────────────────────")

model_ne = LinearRegressionNormalEq()

model_ne.fit(X_train_s, y_train)

r2_ne_train = model_ne.score(X_train_s, y_train)

r2_ne_test = model_ne.score(X_test_s, y_test)

print(f" Train R²: {r2_ne_train:.4f}")

print(f" Test R²: {r2_ne_test:.4f}")

print(" (Normal equation: exact solution, no iterations)")

# ── 5. Visualise ─────────────────────────────────────────────

model_gd.plot_cost(title="Training Cost — House Price Model")

# Actual vs predicted scatter

y_pred_test = model_gd.predict(X_test_s)

plt.figure(figsize=(7, 6))

plt.scatter(y_test / 1000, y_pred_test / 1000,

alpha=0.5, color='steelblue', s=30)

plt.plot([y_test.min()/1000, y_test.max()/1000],

[y_test.min()/1000, y_test.max()/1000],

'r--', linewidth=1.5, label='Perfect prediction')

plt.xlabel("Actual Price ($k)")

plt.ylabel("Predicted Price ($k)")

plt.title("Actual vs. Predicted House Prices")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Expected Output (approximate):

─── Gradient Descent ───────────────────────────────────

Iter 0 | Cost: 5,432,801,234.123456

Iter 100 | Cost: 891,234,111.445678

Iter 200 | Cost: 890,112,003.112233

...

Iter 1900 | Cost: 888,975,001.009900

=============================================

Linear Regression — Parameter Summary

=============================================

sqft : +86,412.3201

bedrooms : +6,843.1102

age : -3,981.8807

dist_center : -5,102.4452

bias (intercept) : +220,981.4417

=============================================

Final training cost: 888,975,001.009900

=============================================

Train R²: 0.9681

Test R²: 0.9655

RMSE: $14,823

MAE: $11,944

─── Normal Equation ─────────────────────────────────────

Train R²: 0.9682

Test R²: 0.9656

(Normal equation: exact solution, no iterations)Both methods reach essentially the same answer. The normal equation is exact; gradient descent converges to it.

Diagnosing Training: Reading the Cost Curve

The cost curve tells you whether training is working correctly.

Good Training

Cost

│╲

│ ╲

│ ╲

│ ╲__________

│ ‾‾‾‾ (flattens = converged)

└─────────────────── IterationSigns: Smooth decrease, then plateau. Learning rate is appropriate.

Learning Rate Too High

Cost

│ /\/\/\/\ (oscillates)

│ ↗ (may diverge upward)

└─────────── IterationFix: Reduce learning rate by 10x.

Learning Rate Too Low

Cost

│╲

│ ╲

│ ╲

│ ╲

│ ╲ (still decreasing at end — not converged)

└─────────── IterationFix: Increase learning rate or add more iterations.

Good vs. Poor Learning Rates — Comparison

# Experiment with different learning rates

learning_rates = [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.5]

colors = ['blue', 'green', 'orange', 'red']

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 5))

for lr, color in zip(learning_rates, colors):

model = LinearRegressionGD(learning_rate=lr, n_iterations=300)

model.fit(X_train_s, y_train)

plt.plot(model.cost_history, color=color,

label=f"lr={lr}", linewidth=1.5)

plt.xlabel("Iteration")

plt.ylabel("Cost")

plt.title("Effect of Learning Rate on Convergence")

plt.legend()

plt.yscale('log') # Log scale shows all curves clearly

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Feature Scaling: Why It Matters

One of the most important practical considerations.

# ── Demonstrate effect of scaling on convergence ─────────────

print("WITHOUT scaling:")

model_unscaled = LinearRegressionGD(learning_rate=0.0001,

n_iterations=5000)

model_unscaled.fit(X_train, y_train) # Raw, unscaled features

r2_unscaled = model_unscaled.score(X_train, y_train)

print(f" Train R²: {r2_unscaled:.4f}")

print(f" Final cost: {model_unscaled.cost_history[-1]:.2f}")

print("\nWITH scaling:")

model_scaled = LinearRegressionGD(learning_rate=0.1,

n_iterations=500)

model_scaled.fit(X_train_s, y_train) # Standardised features

r2_scaled = model_scaled.score(X_train_s, y_train)

print(f" Train R²: {r2_scaled:.4f}")

print(f" Final cost: {model_scaled.cost_history[-1]:.2f}")Why scaling matters:

Unscaled features:

sqft: 800 – 3500 (scale ~1000)

bedrooms: 1 – 5 (scale ~1)

age: 0 – 50 (scale ~10)

dist_center: 0.5 – 30 (scale ~10)

Cost landscape: Very elongated, narrow valley

Gradient descent: Bounces side-to-side, converges slowly

Scaled features:

All features: mean=0, std=1

Cost landscape: Roughly spherical bowl

Gradient descent: Goes straight to minimum, converges fastGradient Checking: Verifying Your Implementation

Always verify gradient computations are correct.

def numerical_gradient(X, y, w, b, epsilon=1e-5):

"""

Compute gradients numerically using finite differences.

Use this to verify analytical gradients are correct.

∂J/∂wᵢ ≈ [J(wᵢ+ε) - J(wᵢ-ε)] / (2ε)

"""

dw_numerical = np.zeros_like(w)

for i in range(len(w)):

w_plus = w.copy(); w_plus[i] += epsilon

w_minus = w.copy(); w_minus[i] -= epsilon

cost_plus = (1/(2*len(y))) * np.sum((X @ w_plus + b - y)**2)

cost_minus = (1/(2*len(y))) * np.sum((X @ w_minus + b - y)**2)

dw_numerical[i] = (cost_plus - cost_minus) / (2 * epsilon)

# Gradient for bias

b_plus = b + epsilon

b_minus = b - epsilon

cost_plus = (1/(2*len(y))) * np.sum((X @ w + b_plus - y)**2)

cost_minus = (1/(2*len(y))) * np.sum((X @ w + b_minus - y)**2)

db_numerical = (cost_plus - cost_minus) / (2 * epsilon)

return dw_numerical, db_numerical

def gradient_check(X, y, w, b):

"""Compare analytical vs numerical gradients."""

# Analytical gradients

m = len(y)

errors = X @ w + b - y

dw_analytical = (1/m) * (X.T @ errors)

db_analytical = (1/m) * np.sum(errors)

# Numerical gradients

dw_numerical, db_numerical = numerical_gradient(X, y, w, b)

# Relative difference

diff_w = np.linalg.norm(dw_analytical - dw_numerical) / \

(np.linalg.norm(dw_analytical) + np.linalg.norm(dw_numerical) + 1e-8)

diff_b = abs(db_analytical - db_numerical) / \

(abs(db_analytical) + abs(db_numerical) + 1e-8)

print("Gradient Check Results:")

print(f" Weight gradient difference: {diff_w:.2e}")

print(f" Bias gradient difference: {diff_b:.2e}")

threshold = 1e-5

if diff_w < threshold and diff_b < threshold:

print(" ✓ PASSED — Gradients are correct!")

else:

print(" ✗ FAILED — Check your gradient formulas.")

# Run check on a small example

X_small = X_train_s[:20]

y_small = y_train[:20]

w_test = np.random.randn(X_small.shape[1]) * 0.1

b_test = 0.0

gradient_check(X_small, y_small, w_test, b_test)Expected Output:

Gradient Check Results:

Weight gradient difference: 3.14e-10

Bias gradient difference: 1.87e-11

✓ PASSED — Gradients are correct!A difference below 1e-5 confirms your gradient formulas are implemented correctly. This technique generalises to any neural network layer.

Comparing Implementations: GD vs. Normal Equation

| Aspect | Gradient Descent | Normal Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Approach | Iterative, approximate | Analytical, exact |

| Iterations needed | Yes (n_iterations) | No (one computation) |

| Learning rate | Required, sensitive | Not needed |

| Feature scaling | Required | Not required |

| Speed — small data | Slower (many iterations) | Faster (one step) |

| Speed — large data (n large) | Fast | Slow (O(n³) inversion) |

| Memory | Low | High (stores X^T X) |

| Extends to deep learning | Yes (same algorithm!) | No |

| Handles singular matrices | Yes (via regularisation) | Needs care (lstsq) |

| Best for | Large datasets, NN foundations | Small-medium datasets |

Adding Regularisation: Ridge Regression

Extend the implementation with L2 regularisation to prevent overfitting.

class RidgeRegressionGD(LinearRegressionGD):

"""

Ridge Regression (L2 regularised linear regression).

Adds penalty λ × ||w||² to the cost function,

shrinking weights toward zero to prevent overfitting.

"""

def __init__(self, learning_rate=0.01, n_iterations=1000,

lambda_=0.1, verbose=False):

super().__init__(learning_rate, n_iterations, verbose)

self.lambda_ = lambda_ # Regularisation strength

def _cost(self, X, y):

"""MSE + L2 penalty (don't penalise bias)."""

base_cost = super()._cost(X, y)

l2_penalty = (self.lambda_ / (2 * len(y))) * np.sum(self.w_ ** 2)

return base_cost + l2_penalty

def _gradients(self, X, y):

"""Add L2 gradient to weight gradient (not bias)."""

m = len(y)

dw, db = super()._gradients(X, y)

dw += (self.lambda_ / m) * self.w_ # Regularise weights only

return dw, db

# Compare Ridge vs plain on a small, noisy dataset

np.random.seed(0)

X_small = X_train_s[:50]

y_small = y_train[:50]

model_plain = LinearRegressionGD(learning_rate=0.1, n_iterations=1000)

model_ridge = RidgeRegressionGD(learning_rate=0.1, n_iterations=1000,

lambda_=10.0)

model_plain.fit(X_small, y_small)

model_ridge.fit(X_small, y_small)

print("Small dataset (50 examples):")

print(f" Plain — Train R²: {model_plain.score(X_small, y_small):.4f} "

f"Test R²: {model_plain.score(X_test_s, y_test):.4f}")

print(f" Ridge — Train R²: {model_ridge.score(X_small, y_small):.4f} "

f"Test R²: {model_ridge.score(X_test_s, y_test):.4f}")Putting It All Together: Recommended Workflow

def full_linear_regression_pipeline(X, y, feature_names=None,

test_size=0.2, lr=0.1,

n_iter=2000, verbose=False):

"""

End-to-end linear regression pipeline from scratch.

1. Split data

2. Scale features

3. Train (gradient descent)

4. Evaluate

5. Report

"""

# 1. Split

X_tr, X_te, y_tr, y_te = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=test_size, random_state=42

)

# 2. Scale

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_tr_s = scaler.fit_transform(X_tr)

X_te_s = scaler.transform(X_te)

# 3. Train

model = LinearRegressionGD(learning_rate=lr,

n_iterations=n_iter,

verbose=verbose)

model.fit(X_tr_s, y_tr)

# 4. Evaluate

results = {

"train_r2": model.score(X_tr_s, y_tr),

"test_r2": model.score(X_te_s, y_te),

"test_rmse": model.rmse(X_te_s, y_te),

"test_mae": model.mae(X_te_s, y_te),

}

# 5. Report

print("\n══════════════════════════════════")

print(" PIPELINE RESULTS")

print("══════════════════════════════════")

print(f" Train R²: {results['train_r2']:.4f}")

print(f" Test R²: {results['test_r2']:.4f}")

print(f" Test RMSE: {results['test_rmse']:.4f}")

print(f" Test MAE: {results['test_mae']:.4f}")

print("══════════════════════════════════")

model.summary(feature_names)

model.plot_cost()

return model, scaler, results

# Run the full pipeline

model, scaler, results = full_linear_regression_pipeline(

X, y,

feature_names=feature_names,

lr=0.1,

n_iter=2000

)Conclusion: What You’ve Built and Why It Matters

You now have a complete linear regression library built from first principles — no scikit-learn, no magic. Let’s reflect on what each piece means beyond this algorithm.

The prediction function ŷ = Xw + b is identical to a single linear neuron. Add a non-linear activation, stack multiple layers, and you have a neural network. The forward pass in GPT-4 is millions of this same computation.

The cost function MSE appears throughout machine learning — in regression neural networks, autoencoders, and generative models. Understanding why you square the errors (differentiability, penalising large errors) transfers directly.

The gradient formulas dw = (1/m) Xᵀ(ŷ - y) are backpropagation for a one-layer network. The chain rule you applied here is the exact same rule applied recursively in deep networks.

Gradient checking is a universal debugging technique. Any time you implement a new neural network layer and aren’t sure your gradient is correct, finite differences will tell you.

Feature scaling is non-negotiable for gradient descent. This lesson applies to every neural network you train — always normalise your inputs.

The normal equation shows that some problems have exact solutions. Understanding when to use closed-form solutions versus iterative ones is a recurring decision in machine learning engineering.

Building linear regression from scratch isn’t just an exercise — it’s building the mental model that makes everything else in machine learning comprehensible. The practitioners who deeply understand this foundation debug neural networks faster, tune hyperparameters more intelligently, and design better architectures. That’s the real value of building it yourself.