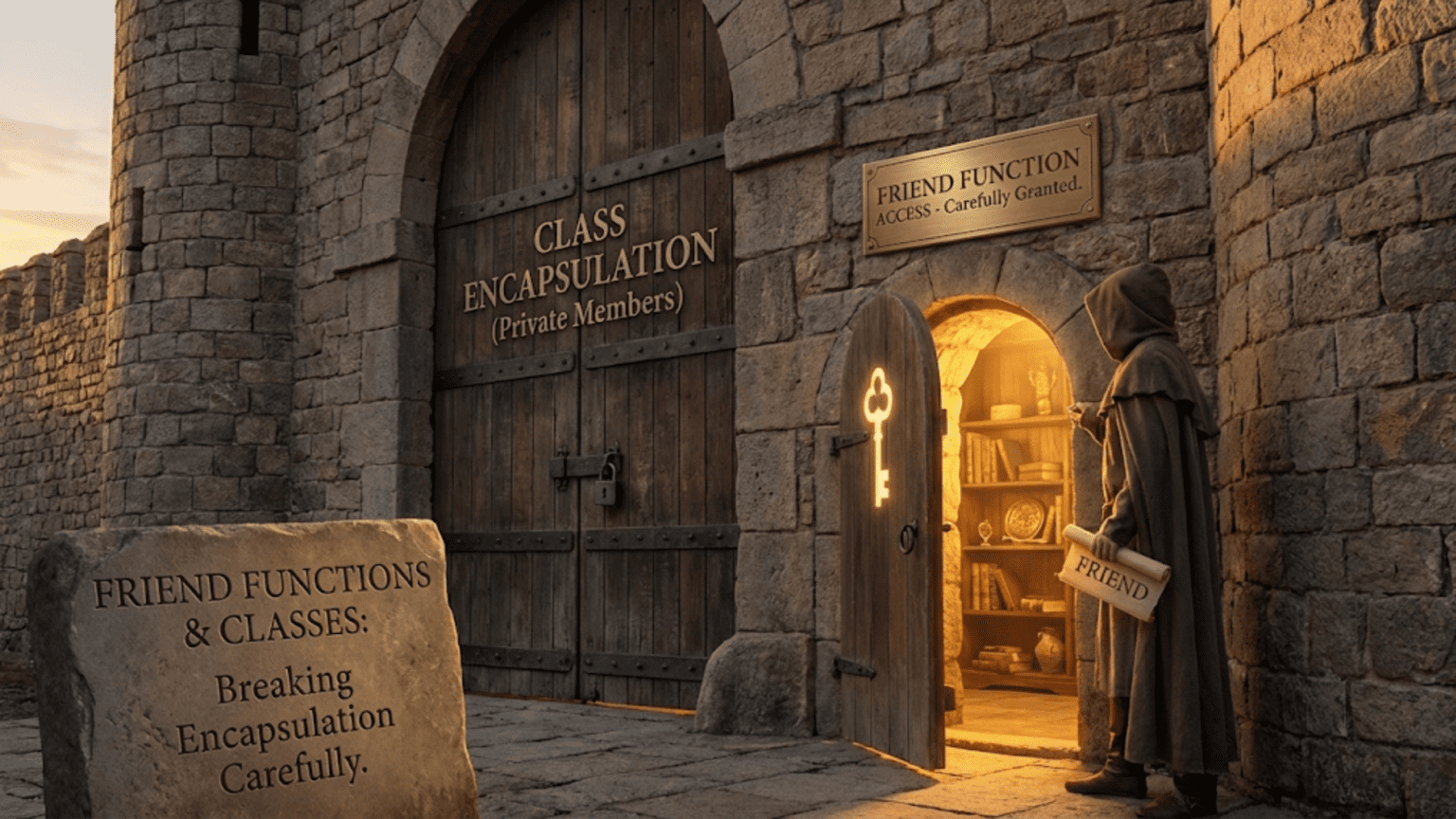

Friend functions and classes in C++ are mechanisms that grant external functions or classes access to the private and protected members of another class, intentionally breaking encapsulation in a controlled manner. Declared using the friend keyword, they enable specific external code to access internal implementation details while maintaining overall data hiding from the rest of the program.

Introduction: The Controlled Exception to Encapsulation

Encapsulation is a cornerstone of object-oriented programming in C++, protecting class internals from unauthorized access. However, there are legitimate scenarios where strict encapsulation becomes an obstacle rather than a benefit. Friend functions and classes provide a controlled mechanism to break encapsulation when necessary, allowing specific external code to access private members while maintaining protection from everything else.

Think of friendship in C++ like giving a trusted friend the key to your house. You don’t hand out keys to everyone—that would defeat the purpose of having locks. But for specific trusted individuals, access makes perfect sense. In programming, certain functions or classes have such an intimate relationship that denying them access to implementation details creates awkward, inefficient code.

Common scenarios where friend declarations prove invaluable include operator overloading (especially stream operators), tightly coupled classes that work together, testing frameworks that need to verify internal state, and optimization where external functions need direct access for performance. The key is using friendship judiciously—it’s a powerful tool that should be applied thoughtfully, not carelessly.

This comprehensive guide will explore friend functions and classes in depth, showing you when to use them, how to implement them correctly, and most importantly, when to avoid them. You’ll learn the syntax, understand the implications for your design, and master the patterns that make friendship beneficial rather than problematic.

What Are Friend Functions?

A friend function is a function that’s not a member of a class but has been granted access to that class’s private and protected members. You declare friendship inside the class using the friend keyword.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Box {

private:

double width;

double height;

double depth;

public:

Box(double w, double h, double d) : width(w), height(h), depth(d) {

cout << "Box created: " << width << "x" << height << "x" << depth << endl;

}

// Declare printBox as a friend function

friend void printBox(const Box& box);

// Declare calculateVolume as a friend function

friend double calculateVolume(const Box& box);

};

// Friend function implementation - NOT a member function

void printBox(const Box& box) {

// Can access private members because it's a friend

cout << "Box dimensions: "

<< box.width << " x "

<< box.height << " x "

<< box.depth << endl;

}

double calculateVolume(const Box& box) {

// Direct access to private members

return box.width * box.height * box.depth;

}

int main() {

Box myBox(10.5, 20.3, 15.7);

cout << "\n=== Using friend functions ===" << endl;

printBox(myBox);

double volume = calculateVolume(myBox);

cout << "Volume: " << volume << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Box class: Contains three private members (width, height, depth)

- Private members: Normally inaccessible from outside the class

- friend keyword: Declares printBox and calculateVolume as friends

- Friend declaration: Placed inside the class definition, can be in any access section

- Function implementation: printBox is defined outside the class (not a member)

- Private access: printBox can directly access box.width, box.height, box.depth

- No ‘this’ pointer: Friend functions don’t have implicit ‘this’ because they’re not members

- calculateVolume friend: Another example accessing private members for computation

- Function call: Called like regular functions, not through object.method() syntax

- Encapsulation maintained: Only these specific functions have access, not all code

- Clear declaration: Friendship is explicitly declared, not hidden

- One-way relationship: Box grants access to functions, but functions don’t grant access to Box

Output:

Box created: 10.5x20.3x15.7

=== Using friend functions ===

Box dimensions: 10.5 x 20.3 x 15.7

Volume: 3347.205Friend Functions for Operator Overloading

The most common use of friend functions is implementing operator overloading, especially for operators that require symmetric treatment of operands.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Complex {

private:

double real;

double imag;

public:

Complex(double r = 0, double i = 0) : real(r), imag(i) {

cout << "Complex number created: " << real << " + " << imag << "i" << endl;

}

// Friend function for output operator

friend ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Complex& c);

// Friend function for input operator

friend istream& operator>>(istream& is, Complex& c);

// Friend function for binary + operator

friend Complex operator+(const Complex& c1, const Complex& c2);

// Friend function for multiplication

friend Complex operator*(const Complex& c1, const Complex& c2);

// Friend function to allow both "2 * complex" and "complex * 2"

friend Complex operator*(double scalar, const Complex& c);

friend Complex operator*(const Complex& c, double scalar);

};

// Stream output operator - must be friend to access private members

ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Complex& c) {

os << c.real;

if (c.imag >= 0)

os << " + " << c.imag << "i";

else

os << " - " << (-c.imag) << "i";

return os;

}

// Stream input operator

istream& operator>>(istream& is, Complex& c) {

cout << "Enter real part: ";

is >> c.real;

cout << "Enter imaginary part: ";

is >> c.imag;

return is;

}

// Addition operator

Complex operator+(const Complex& c1, const Complex& c2) {

cout << "Adding complex numbers" << endl;

return Complex(c1.real + c2.real, c1.imag + c2.imag);

}

// Multiplication operator

Complex operator*(const Complex& c1, const Complex& c2) {

cout << "Multiplying complex numbers" << endl;

// (a + bi)(c + di) = (ac - bd) + (ad + bc)i

double r = c1.real * c2.real - c1.imag * c2.imag;

double i = c1.real * c2.imag + c1.imag * c2.real;

return Complex(r, i);

}

// Scalar multiplication - scalar on left

Complex operator*(double scalar, const Complex& c) {

cout << "Scalar * complex" << endl;

return Complex(scalar * c.real, scalar * c.imag);

}

// Scalar multiplication - scalar on right

Complex operator*(const Complex& c, double scalar) {

cout << "Complex * scalar" << endl;

return Complex(c.real * scalar, c.imag * scalar);

}

int main() {

Complex c1(3, 4);

Complex c2(1, 2);

cout << "\n=== Displaying complex numbers ===" << endl;

cout << "c1 = " << c1 << endl;

cout << "c2 = " << c2 << endl;

cout << "\n=== Addition ===" << endl;

Complex c3 = c1 + c2;

cout << "c1 + c2 = " << c3 << endl;

cout << "\n=== Multiplication ===" << endl;

Complex c4 = c1 * c2;

cout << "c1 * c2 = " << c4 << endl;

cout << "\n=== Scalar multiplication ===" << endl;

Complex c5 = 2 * c1; // Uses scalar * Complex

cout << "2 * c1 = " << c5 << endl;

Complex c6 = c2 * 3; // Uses Complex * scalar

cout << "c2 * 3 = " << c6 << endl;

cout << "\n=== Chained operations ===" << endl;

Complex result = (c1 + c2) * 2;

cout << "(c1 + c2) * 2 = " << result << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Complex class: Represents complex numbers with real and imaginary parts

- Private members: real and imag are hidden from external access

- Friend operator<< declaration: Stream operator needs access to private members

- Why friend for <<: operator<< must have ostream& as first parameter, so can’t be a member

- Friend operator>> declaration: Input operator needs to modify private members

- Binary operators as friends: Addition and multiplication need access to both operands’ private data

- ostream& return type: Returns stream reference for chaining (cout << c1 << c2)

- Accessing private data: Implementation directly uses c.real and c.imag

- Two scalar operators: One for each order (scalar * complex, complex * scalar)

- Symmetric operations: Friend functions treat both operands equally

- No member access syntax: Called as regular functions, not object.method()

- Complex arithmetic: Implements proper complex number multiplication formula

- Operator chaining: Multiple operations can be combined in single expression

- Natural syntax: Friend functions enable mathematical notation

Output:

Complex number created: 3 + 4i

Complex number created: 1 + 2i

=== Displaying complex numbers ===

c1 = 3 + 4i

c2 = 1 + 2i

=== Addition ===

Adding complex numbers

Complex number created: 4 + 6i

c1 + c2 = 4 + 6i

=== Multiplication ===

Multiplying complex numbers

Complex number created: -5 + 10i

c1 * c2 = -5 + 10i

=== Scalar multiplication ===

Scalar * complex

Complex number created: 6 + 8i

2 * c1 = 6 + 8i

Complex * scalar

Complex number created: 3 + 6i

c2 * 3 = 3 + 6i

=== Chained operations ===

Adding complex numbers

Complex number created: 4 + 6i

Complex * scalar

Complex number created: 8 + 12i

(c1 + c2) * 2 = 8 + 12iFriend Classes: Granting Full Access

A friend class has access to all private and protected members of the class that declares it as a friend. This creates a tight coupling between classes.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Engine {

private:

int horsepower;

double fuelEfficiency;

string engineType;

bool isRunning;

// Private helper function

void startCombustion() {

cout << "Combustion started in " << engineType << " engine" << endl;

isRunning = true;

}

public:

Engine(int hp, double efficiency, string type)

: horsepower(hp), fuelEfficiency(efficiency),

engineType(type), isRunning(false) {

cout << "Engine created: " << hp << "hp " << type << endl;

}

// Declare Car as a friend class

friend class Car;

// Declare Mechanic as a friend class

friend class Mechanic;

void displayPublicInfo() {

cout << "Engine: " << horsepower << "hp, Type: " << engineType << endl;

}

};

class Car {

private:

string brand;

Engine engine;

public:

Car(string b, int hp, double efficiency, string engineType)

: brand(b), engine(hp, efficiency, engineType) {

cout << "Car created: " << brand << endl;

}

void start() {

cout << brand << " starting..." << endl;

// Can access private members of Engine because Car is friend

if (!engine.isRunning) {

engine.startCombustion(); // Access private method

cout << "Engine with " << engine.horsepower

<< "hp is now running" << endl;

} else {

cout << "Engine already running" << endl;

}

}

void displayCarInfo() {

cout << "\n=== Car Information ===" << endl;

cout << "Brand: " << brand << endl;

// Access all private members of Engine

cout << "Engine: " << engine.engineType << endl;

cout << "Horsepower: " << engine.horsepower << endl;

cout << "Fuel Efficiency: " << engine.fuelEfficiency << " mpg" << endl;

cout << "Status: " << (engine.isRunning ? "Running" : "Stopped") << endl;

}

};

class Mechanic {

private:

string name;

public:

Mechanic(string n) : name(n) {

cout << "Mechanic: " << name << endl;

}

void inspectEngine(Engine& engine) {

cout << "\n=== " << name << " inspecting engine ===" << endl;

// Can access all private members because Mechanic is friend

cout << "Engine Type: " << engine.engineType << endl;

cout << "Horsepower: " << engine.horsepower << endl;

cout << "Fuel Efficiency: " << engine.fuelEfficiency << " mpg" << endl;

cout << "Running: " << (engine.isRunning ? "Yes" : "No") << endl;

}

void tuneEngine(Engine& engine, int extraHp) {

cout << "\n=== " << name << " tuning engine ===" << endl;

// Direct modification of private members

int oldHp = engine.horsepower;

engine.horsepower += extraHp;

cout << "Horsepower increased from " << oldHp

<< " to " << engine.horsepower << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Creating car ===" << endl;

Car myCar("Tesla", 450, 120, "Electric");

cout << "\n=== Starting car ===" << endl;

myCar.start();

myCar.displayCarInfo();

cout << "\n=== Creating mechanic ===" << endl;

Mechanic mike("Mike");

// Create standalone engine for mechanic to work on

cout << "\n=== Creating standalone engine ===" << endl;

Engine v8Engine(400, 18, "V8");

mike.inspectEngine(v8Engine);

mike.tuneEngine(v8Engine, 50);

mike.inspectEngine(v8Engine);

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Engine class: Contains private implementation details about the engine

- Private members: horsepower, fuelEfficiency, engineType, isRunning all hidden

- startCombustion(): Private helper method normally inaccessible from outside

- friend class Car: Grants Car complete access to all Engine private members

- friend class Mechanic: Grants Mechanic complete access as well

- Multiple friends: A class can have multiple friend classes

- Car class: Contains an Engine object as a member

- Car::start(): Accesses engine.isRunning and calls engine.startCombustion()

- Direct private access: Car treats Engine’s private members like its own

- displayCarInfo(): Reads all Engine private data directly

- Mechanic class: Independent class that works with Engine objects

- inspectEngine(): Reads all private Engine data for diagnostics

- tuneEngine(): Modifies private Engine members directly

- Non-reciprocal: Engine being friend of Car doesn’t make Car friend of Engine

- Tight coupling: Friend classes create strong dependencies between classes

Output:

=== Creating car ===

Engine created: 450hp Electric

Car created: Tesla

=== Starting car ===

Tesla starting...

Combustion started in Electric engine

Engine with 450hp is now running

=== Car Information ===

Brand: Tesla

Engine: Electric

Horsepower: 450

Fuel Efficiency: 120 mpg

Status: Running

=== Creating mechanic ===

Mechanic: Mike

=== Creating standalone engine ===

Engine created: 400hp V8

=== Mike inspecting engine ===

Engine Type: V8

Horsepower: 400

Fuel Efficiency: 18 mpg

Running: No

=== Mike tuning engine ===

Horsepower increased from 400 to 450

=== Mike inspecting engine ===

Engine Type: V8

Horsepower: 450

Fuel Efficiency: 18 mpg

Running: NoFriend Function of Multiple Classes

A function can be a friend to multiple classes, allowing it to work with private data from different classes.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Rectangle; // Forward declaration

class Circle {

private:

double radius;

public:

Circle(double r) : radius(r) {

cout << "Circle created with radius: " << radius << endl;

}

// Declare compareAreas as friend

friend void compareAreas(const Circle& c, const Rectangle& r);

double getArea() const {

return 3.14159 * radius * radius;

}

};

class Rectangle {

private:

double width;

double height;

public:

Rectangle(double w, double h) : width(w), height(h) {

cout << "Rectangle created: " << width << "x" << height << endl;

}

// Declare compareAreas as friend

friend void compareAreas(const Circle& c, const Rectangle& r);

double getArea() const {

return width * height;

}

};

// Friend function of both Circle and Rectangle

void compareAreas(const Circle& c, const Rectangle& r) {

cout << "\n=== Comparing Areas ===" << endl;

// Access Circle's private members

double circleArea = 3.14159 * c.radius * c.radius;

cout << "Circle (radius " << c.radius << "): " << circleArea << endl;

// Access Rectangle's private members

double rectArea = r.width * r.height;

cout << "Rectangle (" << r.width << "x" << r.height << "): " << rectArea << endl;

if (circleArea > rectArea) {

cout << "Circle has larger area by " << (circleArea - rectArea) << endl;

} else if (rectArea > circleArea) {

cout << "Rectangle has larger area by " << (rectArea - circleArea) << endl;

} else {

cout << "Both shapes have equal area" << endl;

}

}

int main() {

Circle myCircle(5.0);

Rectangle myRect(8.0, 6.0);

// Friend function can access private members of both classes

compareAreas(myCircle, myRect);

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Forward declaration:

class Rectangle;tells compiler Rectangle exists before defining it - Circle class: Contains private radius member

- Friend declaration in Circle: Declares compareAreas as friend

- Rectangle class: Contains private width and height

- Friend declaration in Rectangle: Also declares compareAreas as friend

- compareAreas function: Friend to both Circle and Rectangle

- Access Circle private: Can directly access c.radius

- Access Rectangle private: Can directly access r.width and r.height

- Cross-class operations: Function works with private data from both classes

- Why friend needed: Public getArea() methods could work, but direct access may be more efficient

- Single implementation: One function handles both classes’ private data

- Use case: Common in comparison, conversion, or bridging functions

Output:

Circle created with radius: 5

Rectangle created: 8x6

=== Comparing Areas ===

Circle (radius 5): 78.5397

Rectangle (8x6): 48

Circle has larger area by 30.5397Friend Member Functions

Instead of making an entire class a friend, you can make specific member functions friends, providing more granular access control.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Display; // Forward declaration

class Data {

private:

int value;

string description;

public:

Data(int v, string desc) : value(v), description(desc) {

cout << "Data created: " << description << " = " << value << endl;

}

// Only specific Display member functions are friends

friend void Display::showValue(const Data& d);

friend void Display::modifyValue(Data& d, int newVal);

// Note: Display::showDescription is NOT a friend

};

class Display {

public:

void showValue(const Data& d) {

// Can access private value because it's a friend

cout << "Value: " << d.value << endl;

}

void modifyValue(Data& d, int newVal) {

// Can access and modify private value

cout << "Changing value from " << d.value << " to " << newVal << endl;

d.value = newVal;

}

void showDescription(const Data& d) {

// Cannot access private description - NOT a friend

// cout << d.description << endl; // ERROR!

cout << "Description access denied (not a friend)" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

Data myData(42, "Test Data");

Display display;

cout << "\n=== Using friend member functions ===" << endl;

display.showValue(myData);

display.modifyValue(myData, 100);

display.showValue(myData);

cout << "\n=== Trying non-friend function ===" << endl;

display.showDescription(myData);

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Forward declaration: Display class declared before Data to allow friend declarations

- Selective friendship: Only specific Display methods are friends, not entire class

- friend Display::showValue: Grants this specific method access to private members

- friend Display::modifyValue: Another specific method granted access

- showDescription NOT friend: This method cannot access Data’s private members

- More granular control: More restrictive than making whole class a friend

- Access pattern: Friend methods can read and write private members

- Non-friend pattern: showDescription() cannot access d.description

- Compilation requirement: Display must be fully defined before Data for this to work

- Use case: When only specific operations need privileged access

Note: The code above requires Display to be fully defined before Data, so in practice you’d need to restructure:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Data; // Forward declaration

class Display {

public:

void showValue(const Data& d);

void modifyValue(Data& d, int newVal);

void showDescription(const Data& d);

};

class Data {

private:

int value;

string description;

public:

Data(int v, string desc) : value(v), description(desc) {

cout << "Data created: " << description << " = " << value << endl;

}

friend void Display::showValue(const Data& d);

friend void Display::modifyValue(Data& d, int newVal);

};

// Now implement Display methods

void Display::showValue(const Data& d) {

cout << "Value: " << d.value << endl;

}

void Display::modifyValue(Data& d, int newVal) {

cout << "Changing value from " << d.value << " to " << newVal << endl;

d.value = newVal;

}

void Display::showDescription(const Data& d) {

// Cannot access description - not a friend

cout << "Description access denied (not a friend)" << endl;

}

int main() {

Data myData(42, "Test Data");

Display display;

cout << "\n=== Using friend member functions ===" << endl;

display.showValue(myData);

display.modifyValue(myData, 100);

display.showValue(myData);

cout << "\n=== Trying non-friend function ===" << endl;

display.showDescription(myData);

return 0;

}Output:

Data created: Test Data = 42

=== Using friend member functions ===

Value: 42

Changing value from 42 to 100

Value: 100

=== Trying non-friend function ===

Description access denied (not a friend)

When to Use Friend Functions and Classes

Friends should be used sparingly and only when there’s a compelling reason. Here are legitimate use cases:

#include <iostream>

#include <cmath>

using namespace std;

// Use Case 1: Operator Overloading for Symmetric Operations

class Vector3D {

private:

double x, y, z;

public:

Vector3D(double x = 0, double y = 0, double z = 0) : x(x), y(y), z(z) {}

// Friend for symmetric scalar multiplication

friend Vector3D operator*(double scalar, const Vector3D& v);

friend Vector3D operator*(const Vector3D& v, double scalar);

friend ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Vector3D& v);

};

Vector3D operator*(double scalar, const Vector3D& v) {

return Vector3D(scalar * v.x, scalar * v.y, scalar * v.z);

}

Vector3D operator*(const Vector3D& v, double scalar) {

return scalar * v; // Reuse above operator

}

ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Vector3D& v) {

os << "(" << v.x << ", " << v.y << ", " << v.z << ")";

return os;

}

// Use Case 2: Tightly Coupled Classes with Shared Implementation

class Node {

private:

int data;

Node* next;

friend class LinkedList; // LinkedList needs to manipulate Node internals

public:

Node(int d) : data(d), next(nullptr) {}

};

class LinkedList {

private:

Node* head;

public:

LinkedList() : head(nullptr) {}

void insert(int value) {

Node* newNode = new Node(value);

// Can access private Node members

newNode->next = head;

head = newNode;

cout << "Inserted " << value << endl;

}

void display() {

cout << "List: ";

Node* current = head;

while (current != nullptr) {

// Can access private data member

cout << current->data << " ";

current = current->next;

}

cout << endl;

}

~LinkedList() {

while (head != nullptr) {

Node* temp = head;

head = head->next;

delete temp;

}

}

};

// Use Case 3: Testing and Debugging

class BankAccount {

private:

double balance;

string accountNumber;

public:

BankAccount(string accNum, double initial)

: accountNumber(accNum), balance(initial) {}

void deposit(double amount) {

if (amount > 0) balance += amount;

}

bool withdraw(double amount) {

if (amount > 0 && balance >= amount) {

balance -= amount;

return true;

}

return false;

}

// Friend for unit testing

friend class BankAccountTester;

};

class BankAccountTester {

public:

static void verifyInternalState(const BankAccount& account) {

cout << "\n=== Test: Verify Internal State ===" << endl;

cout << "Account Number: " << account.accountNumber << endl;

cout << "Balance: $" << account.balance << endl;

// Can verify private state for testing

if (account.balance >= 0) {

cout << "PASS: Balance is non-negative" << endl;

} else {

cout << "FAIL: Balance is negative!" << endl;

}

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Use Case 1: Operator Overloading ===" << endl;

Vector3D v(1, 2, 3);

cout << "v = " << v << endl;

cout << "2 * v = " << (2 * v) << endl;

cout << "v * 3 = " << (v * 3) << endl;

cout << "\n=== Use Case 2: Tightly Coupled Classes ===" << endl;

LinkedList list;

list.insert(10);

list.insert(20);

list.insert(30);

list.display();

cout << "\n=== Use Case 3: Testing ===" << endl;

BankAccount account("ACC-001", 1000);

account.deposit(500);

account.withdraw(200);

BankAccountTester::verifyInternalState(account);

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Vector3D class: Uses friends for symmetric scalar multiplication operators

- operator friends*: Both scalarvector and vectorscalar need access to x, y, z

- Symmetry requirement: 2v and v2 should both work naturally

- Stream operator: operator<< needs access to display private coordinates

- Node class: Represents linked list node with private data and next pointer

- LinkedList friend: Node declares LinkedList as friend

- Tight coupling: Node and LinkedList are inherently coupled—Node exists only for LinkedList

- Internal manipulation: LinkedList directly manipulates Node’s next pointer

- Encapsulation preserved: External code can’t access Node internals, only LinkedList

- BankAccount class: Normal banking operations with encapsulated balance

- BankAccountTester friend: Testing class needs to verify internal state

- Test access: Can check private balance and accountNumber for verification

- Testing necessity: Unit tests often need to verify internal state

- Three valid scenarios: Operators, tightly coupled classes, and testing

Output:

=== Use Case 1: Operator Overloading ===

v = (1, 2, 3)

2 * v = (2, 4, 6)

v * 3 = (3, 6, 9)

=== Use Case 2: Tightly Coupled Classes ===

Inserted 30

Inserted 20

Inserted 10

List: 30 20 10

=== Use Case 3: Testing ===

=== Test: Verify Internal State ===

Account Number: ACC-001

Balance: $1300

PASS: Balance is non-negativeFriendship is Not Inherited or Transitive

Important characteristics of friendship that affect design decisions:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base {

private:

int baseSecret;

public:

Base(int secret) : baseSecret(secret) {

cout << "Base created with secret: " << baseSecret << endl;

}

friend class FriendOfBase;

};

class Derived : public Base {

private:

int derivedSecret;

public:

Derived(int baseSecret, int derived)

: Base(baseSecret), derivedSecret(derived) {

cout << "Derived created with additional secret: " << derivedSecret << endl;

}

};

class FriendOfBase {

public:

void accessBase(Base& b) {

cout << "\n=== FriendOfBase accessing Base ===" << endl;

// Can access Base's private members

cout << "Base secret: " << b.baseSecret << endl;

}

void accessDerived(Derived& d) {

cout << "\n=== FriendOfBase accessing Derived ===" << endl;

// Can access inherited Base members

cout << "Base secret from Derived: " << d.baseSecret << endl;

// CANNOT access Derived's own private members

// cout << "Derived secret: " << d.derivedSecret << endl; // ERROR!

cout << "Cannot access Derived's own private members" << endl;

}

};

class AnotherClass {

private:

int value;

public:

AnotherClass(int v) : value(v) {}

friend class ClassA;

};

class ClassA {

private:

int data;

public:

ClassA(int d) : data(d) {}

friend class ClassB;

void accessAnother(AnotherClass& other) {

// Can access AnotherClass private members

cout << "ClassA accessing AnotherClass: " << other.value << endl;

}

};

class ClassB {

public:

void accessA(ClassA& a) {

// Can access ClassA private members (friend of ClassA)

cout << "ClassB accessing ClassA: " << a.data << endl;

}

void accessAnother(AnotherClass& other) {

// CANNOT access AnotherClass (friendship not transitive)

// cout << other.value << endl; // ERROR!

cout << "ClassB cannot access AnotherClass (friendship not transitive)" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Testing Inheritance ===" << endl;

Base base(100);

Derived derived(200, 300);

FriendOfBase friendObj;

friendObj.accessBase(base);

friendObj.accessDerived(derived);

cout << "\n=== Testing Transitivity ===" << endl;

AnotherClass another(999);

ClassA objA(111);

ClassB objB;

objA.accessAnother(another); // Works - ClassA is friend of AnotherClass

objB.accessA(objA); // Works - ClassB is friend of ClassA

objB.accessAnother(another); // Fails - friendship not transitive

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Base class: Has private baseSecret and declares FriendOfBase as friend

- Derived class: Inherits from Base, adds its own private derivedSecret

- Friendship not inherited: FriendOfBase is friend of Base, NOT automatically friend of Derived

- Access to inherited members: FriendOfBase can access baseSecret even in Derived object

- No access to new members: FriendOfBase cannot access derivedSecret

- AnotherClass: Declares ClassA as friend

- ClassA: Declares ClassB as friend

- ClassB friend of ClassA: Can access ClassA’s private data

- Friendship not transitive: ClassB is NOT friend of AnotherClass even though ClassA is

- Chain breaks: Friend of friend is not automatically friend

- Explicit declaration needed: Each class must explicitly declare its friends

- Design implication: Can’t grant access indirectly through intermediary

Output:

=== Testing Inheritance ===

Base created with secret: 100

Base created with secret: 200

Derived created with additional secret: 300

=== FriendOfBase accessing Base ===

Base secret: 100

=== FriendOfBase accessing Derived ===

Base secret from Derived: 200

Cannot access Derived's own private members

=== Testing Transitivity ===

ClassA accessing AnotherClass: 999

ClassB accessing ClassA: 111

ClassB cannot access AnotherClass (friendship not transitive)Alternatives to Friend Functions

Before using friends, consider these alternatives that maintain better encapsulation:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// Alternative 1: Public Getters (Preferred when possible)

class Point {

private:

double x, y;

public:

Point(double x = 0, double y = 0) : x(x), y(y) {}

// Public accessors instead of friend

double getX() const { return x; }

double getY() const { return y; }

};

// No friend needed - use public interface

double calculateDistance(const Point& p1, const Point& p2) {

double dx = p1.getX() - p2.getX();

double dy = p1.getY() - p2.getY();

return sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy);

}

// Alternative 2: Member Function (When operation belongs to class)

class Counter {

private:

int value;

public:

Counter(int v = 0) : value(v) {}

// Member function instead of friend

Counter add(const Counter& other) const {

return Counter(value + other.value);

}

// Or use operator overloading as member

Counter operator+(const Counter& other) const {

return Counter(value + other.value);

}

void display() const {

cout << "Value: " << value << endl;

}

};

// Alternative 3: Static Member Function

class MathOperations {

private:

double value;

public:

MathOperations(double v) : value(v) {}

double getValue() const { return value; }

// Static member function instead of friend

static double multiply(const MathOperations& m1, const MathOperations& m2) {

return m1.value * m2.value;

}

static MathOperations add(const MathOperations& m1, const MathOperations& m2) {

return MathOperations(m1.value + m2.value);

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Alternative 1: Public Getters ===" << endl;

Point p1(3, 4);

Point p2(0, 0);

double distance = calculateDistance(p1, p2);

cout << "Distance: " << distance << endl;

cout << "\n=== Alternative 2: Member Functions ===" << endl;

Counter c1(10);

Counter c2(20);

Counter c3 = c1 + c2; // Using member operator+

c3.display();

cout << "\n=== Alternative 3: Static Members ===" << endl;

MathOperations m1(5);

MathOperations m2(3);

double product = MathOperations::multiply(m1, m2);

cout << "Product: " << product << endl;

MathOperations sum = MathOperations::add(m1, m2);

cout << "Sum: " << sum.getValue() << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Point with getters: Instead of friend, provides public accessor methods

- calculateDistance: Uses public getX() and getY() instead of private access

- Maintained encapsulation: No direct access to private members

- Counter with members: Operation implemented as member function

- operator+ as member: First operand is implicit ‘this’, natural for operators

- No friend needed: Member functions have access to own class’s private data

- MathOperations static: Uses static member functions for operations

- Access through getValue(): Even static members use public interface where possible

- When getters work: Simple read access to data is sufficient

- When members work: Operation logically belongs to one of the classes

- When static works: Operation is related to class but doesn’t need object state

- Preference order: Try these before resorting to friend declarations

Output:

=== Alternative 1: Public Getters ===

Distance: 5

=== Alternative 2: Member Functions ===

Value: 30

=== Alternative 3: Static Members ===

Product: 15

Sum: 8Best Practices for Using Friends

When you must use friends, follow these guidelines:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

// GOOD: Friend for operator overloading (legitimate use)

class Money {

private:

long cents; // Store as cents to avoid floating-point issues

public:

Money(double dollars) : cents(static_cast<long>(dollars * 100)) {}

// Friend declaration close to related members

friend ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Money& m);

friend istream& operator>>(istream& is, Money& m);

double getDollars() const {

return cents / 100.0;

}

};

ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Money& m) {

os << "$" << (m.cents / 100) << "."

<< (m.cents % 100 < 10 ? "0" : "") << (m.cents % 100);

return os;

}

istream& operator>>(istream& is, Money& m) {

double dollars;

is >> dollars;

m.cents = static_cast<long>(dollars * 100);

return is;

}

// BAD: Overusing friend (should use public interface)

class BadExample {

private:

int value;

public:

BadExample(int v) : value(v) {}

// TOO MANY friends - breaks encapsulation unnecessarily

friend void function1(BadExample& b);

friend void function2(BadExample& b);

friend void function3(BadExample& b);

friend class HelperClass1;

friend class HelperClass2;

// Better: provide controlled access

int getValue() const { return value; }

void setValue(int v) { value = v; }

};

// GOOD: Document why friendship is needed

class SecureData {

private:

string encryptedData;

public:

SecureData(string data) : encryptedData(data) {}

// Friend for specific purpose (documented)

// Purpose: DecryptionModule needs direct access to encrypted data

// for performance-critical decryption algorithm

friend class DecryptionModule;

// Public interface for other uses

bool isEmpty() const {

return encryptedData.empty();

}

};

class DecryptionModule {

public:

static string decrypt(const SecureData& data) {

// Hypothetical decryption (direct access for performance)

string result = data.encryptedData;

// ... complex decryption ...

return result;

}

};

// GOOD: Minimize scope of friendship

class RestrictedAccess {

private:

int sensitiveData;

int publicData;

public:

RestrictedAccess(int sensitive, int pub)

: sensitiveData(sensitive), publicData(pub) {}

// Only specific function is friend, not entire class

friend int getSensitiveData(const RestrictedAccess& ra);

// Public accessor for public data

int getPublicData() const { return publicData; }

};

int getSensitiveData(const RestrictedAccess& ra) {

return ra.sensitiveData;

}

int main() {

cout << "=== Good Practice: Operator Overloading ===" << endl;

Money price(49.99);

cout << "Price: " << price << endl;

cout << "\n=== Good Practice: Documented Purpose ===" << endl;

SecureData data("encrypted_content");

string decrypted = DecryptionModule::decrypt(data);

cout << "Decryption complete" << endl;

cout << "\n=== Good Practice: Minimal Scope ===" << endl;

RestrictedAccess ra(12345, 67890);

cout << "Public data: " << ra.getPublicData() << endl;

cout << "Sensitive data (via friend): " << getSensitiveData(ra) << endl;

return 0;

}Best practices summary:

- Use friends sparingly: Only when truly necessary

- Document why: Explain why friendship is needed in comments

- Prefer alternatives: Try public interface, member functions, or static functions first

- Minimize scope: Make specific functions friends instead of entire classes

- Group declarations: Keep friend declarations near related code

- Consider maintainability: Friends create tight coupling

- Review regularly: Revisit friend declarations during refactoring

Output:

=== Good Practice: Operator Overloading ===

Price: $49.99

=== Good Practice: Documented Purpose ===

Decryption complete

=== Good Practice: Minimal Scope ===

Public data: 67890

Sensitive data (via friend): 12345Conclusion: Using Friendship Wisely

Friend functions and classes are powerful tools in C++ that allow controlled exceptions to encapsulation. While they can create elegant solutions for specific problems like operator overloading and tightly coupled classes, they should be used judiciously to avoid undermining the benefits of encapsulation.

Key takeaways:

- Friends grant private access to specific functions or classes

- Friendship is not inherited, reciprocal, or transitive

- Most common legitimate use: operator overloading (especially stream operators)

- Valid for tightly coupled classes with shared implementation

- Useful for testing frameworks that need to verify internal state

- Always consider alternatives first: public getters, member functions, static methods

- Document why friendship is necessary when you use it

- Minimize the scope of friendship (prefer friend functions over friend classes)

When you declare something a friend, you’re creating a tight coupling and opening a maintenance burden. Every friend is a promise that the friend will respect the class’s invariants and a potential source of problems if the friend doesn’t live up to that promise. Use friends when the alternative is worse, but always think carefully before breaking encapsulation.

The best approach is to start with strict encapsulation and only add friend declarations when you encounter specific scenarios where the benefits clearly outweigh the costs. Operator overloading for stream I/O is almost always worth it. Making an entire unrelated class a friend rarely is. Exercise good judgment, document your decisions, and your code will benefit from using friendship wisely.