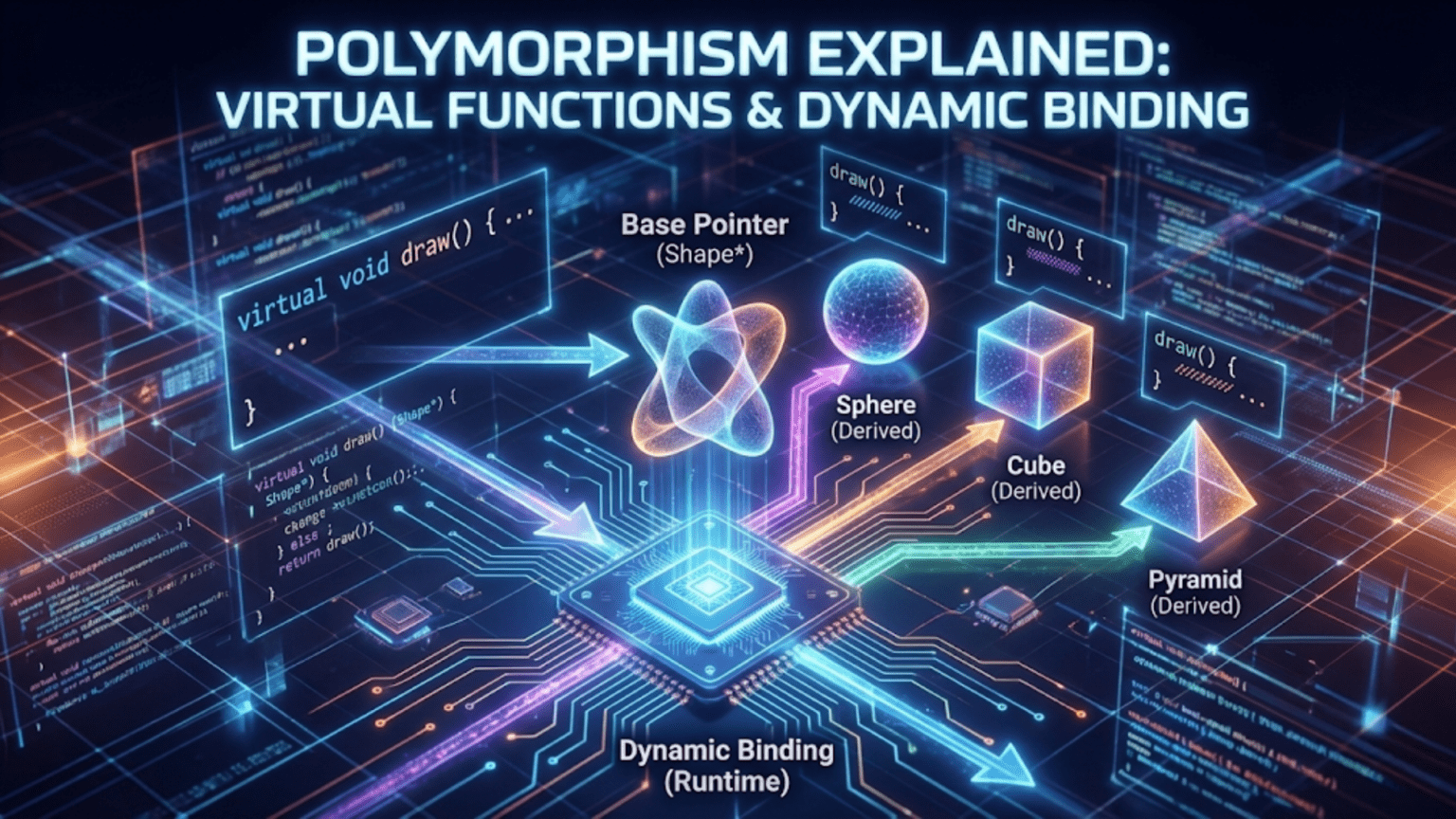

Polymorphism in C++ is an object-oriented programming principle that allows objects of different classes to be treated as objects of a common base class, with the actual method executed determined at runtime through virtual functions and dynamic binding. This enables writing flexible, extensible code where a single interface can represent multiple underlying forms, making programs more modular and easier to maintain.

Introduction: The Power of Many Forms

Polymorphism, derived from Greek words meaning “many forms,” represents one of the most powerful and elegant features in C++ programming. It allows you to write code that works with objects at a high level of abstraction while letting each object behave according to its specific type at runtime. This creates software that is both flexible and maintainable, capable of handling new types without modification.

Imagine you’re building a graphics application that draws shapes. Without polymorphism, you’d need separate code to draw circles, rectangles, triangles, and every other shape. With polymorphism, you write one drawing routine that works with all shapes, and each shape knows how to draw itself. When you add a new shape type, the existing code doesn’t change—it automatically works with the new shape.

This comprehensive guide will take you deep into C++ polymorphism, starting with fundamental concepts and progressing to advanced techniques. You’ll learn how virtual functions enable runtime behavior selection, understand the mechanism of dynamic binding, explore vtables and their performance implications, and master the patterns that make polymorphism so powerful in real-world applications.

What is Polymorphism? Understanding the Concept

Polymorphism enables a single interface to represent different underlying forms. In C++, this means that a pointer or reference to a base class can refer to objects of different derived classes, and the correct method is called based on the actual object type, not the pointer type.

There are two types of polymorphism in C++:

Compile-time polymorphism (static binding): Achieved through function overloading and templates. The compiler determines which function to call at compile time.

Runtime polymorphism (dynamic binding): Achieved through virtual functions and inheritance. The program determines which function to call at runtime based on the actual object type.

This article focuses on runtime polymorphism, which is the more powerful and flexible form.

The Problem Polymorphism Solves

Consider managing different types of employees without polymorphism:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Manager {

public:

string name;

double baseSalary;

double bonus;

double calculatePay() {

return baseSalary + bonus;

}

};

class Developer {

public:

string name;

double baseSalary;

int projectsCompleted;

double calculatePay() {

return baseSalary + (projectsCompleted * 1000);

}

};

class Intern {

public:

string name;

double hourlyRate;

int hoursWorked;

double calculatePay() {

return hourlyRate * hoursWorked;

}

};

// Without polymorphism, you need separate processing for each type

void processManagerPayroll(Manager* managers[], int count) {

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

cout << managers[i]->name << ": $"

<< managers[i]->calculatePay() << endl;

}

}

void processDeveloperPayroll(Developer* developers[], int count) {

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

cout << developers[i]->name << ": $"

<< developers[i]->calculatePay() << endl;

}

}

void processInternPayroll(Intern* interns[], int count) {

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

cout << interns[i]->name << ": $"

<< interns[i]->calculatePay() << endl;

}

}Step-by-step explanation:

- We define three separate classes: Manager, Developer, and Intern, each with their own data members

- Each class has its own calculatePay() method with different calculation logic

- We need three separate functions to process payroll for each employee type

- This approach is rigid—adding a new employee type requires writing a new processing function

- We cannot store different employee types in a single collection

- Code duplication is rampant, violating the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle

This non-polymorphic approach creates maintenance nightmares and inflexible code.

Virtual Functions: The Foundation of Polymorphism

Virtual functions are the mechanism that enables runtime polymorphism in C++. When you declare a function as virtual in a base class, derived classes can override it, and the correct version is called based on the actual object type at runtime.

Basic Virtual Function Example

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Employee {

protected:

string name;

double baseSalary;

public:

Employee(string n, double salary) : name(n), baseSalary(salary) {}

// Virtual function - can be overridden

virtual double calculatePay() {

return baseSalary;

}

// Virtual function for displaying information

virtual void displayInfo() {

cout << "Employee: " << name << endl;

cout << "Pay: $" << calculatePay() << endl;

}

// Virtual destructor (important!)

virtual ~Employee() {

cout << "Employee destructor: " << name << endl;

}

};

class Manager : public Employee {

private:

double bonus;

public:

Manager(string n, double salary, double b)

: Employee(n, salary), bonus(b) {}

// Override virtual function

double calculatePay() override {

return baseSalary + bonus;

}

void displayInfo() override {

cout << "Manager: " << name << endl;

cout << "Base Salary: $" << baseSalary << endl;

cout << "Bonus: $" << bonus << endl;

cout << "Total Pay: $" << calculatePay() << endl;

}

~Manager() {

cout << "Manager destructor: " << name << endl;

}

};

class Developer : public Employee {

private:

int projectsCompleted;

public:

Developer(string n, double salary, int projects)

: Employee(n, salary), projectsCompleted(projects) {}

double calculatePay() override {

return baseSalary + (projectsCompleted * 1000);

}

void displayInfo() override {

cout << "Developer: " << name << endl;

cout << "Projects: " << projectsCompleted << endl;

cout << "Total Pay: $" << calculatePay() << endl;

}

~Developer() {

cout << "Developer destructor: " << name << endl;

}

};

int main() {

// Base class pointer can point to derived class objects

Employee* emp1 = new Manager("Sarah", 80000, 20000);

Employee* emp2 = new Developer("John", 70000, 5);

// Polymorphic behavior - correct method called based on actual type

emp1->displayInfo();

cout << endl;

emp2->displayInfo();

// Proper cleanup with virtual destructor

delete emp1;

delete emp2;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Employee base class: We declare calculatePay() and displayInfo() as virtual functions using the

virtualkeyword - Protected members: baseSalary and name are protected so derived classes can access them

- Virtual destructor: Declared with

virtual ~Employee()to ensure proper cleanup when deleting through base class pointers - Manager class: Inherits from Employee and overrides both virtual functions with the

overridekeyword - Developer class: Also inherits and overrides the virtual functions with its own implementation

- Polymorphic pointers: In main(), Employee pointers (emp1, emp2) point to Manager and Developer objects

- Dynamic binding: When we call displayInfo() through the Employee pointer, the program determines at runtime which version to execute

- Runtime behavior: emp1->displayInfo() calls Manager’s version, emp2->displayInfo() calls Developer’s version

- Virtual destructor in action: When we delete the pointers, both derived class and base class destructors are called in proper order

Output:

Manager: Sarah

Base Salary: $80000

Bonus: $20000

Total Pay: $100000

Developer: John

Projects: 5

Total Pay: $75000

Manager destructor: Sarah

Employee destructor: Sarah

Developer destructor: John

Employee destructor: JohnThe override Keyword: Catching Errors Early

The override keyword (introduced in C++11) explicitly indicates that a function is meant to override a base class virtual function. It helps catch errors at compile time.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base {

public:

virtual void process(int value) {

cout << "Base process: " << value << endl;

}

virtual void display() const {

cout << "Base display" << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

// Correct override

void process(int value) override {

cout << "Derived process: " << value << endl;

}

// This would cause a compilation error with override keyword

// void display() override { // Error! Missing const

// cout << "Derived display" << endl;

// }

// Correct version with const

void display() const override {

cout << "Derived display" << endl;

}

// Not an override - different signature (double vs int)

void process(double value) { // No override keyword - new function

cout << "Derived process double: " << value << endl;

}

};

int main() {

Base* ptr = new Derived();

ptr->process(10); // Calls Derived::process(int)

ptr->display(); // Calls Derived::display()

delete ptr;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Base class virtual functions: process(int) and display() const are declared virtual

- Derived class with override: We use the

overridekeyword when overriding base class functions - Signature matching: The override keyword requires exact signature match (parameters and const-ness)

- Compile-time error detection: If we tried to override display() without const, the compiler would error because the signature doesn’t match

- Non-overriding function: process(double) is not an override because it has a different parameter type—it’s a new function

- Polymorphic call: Through the Base pointer, we call the Derived versions of process() and display()

The override keyword provides two major benefits: it makes code more readable (clear intent) and catches mistakes early (compile-time errors instead of runtime bugs).

Dynamic Binding: How It Works at Runtime

Dynamic binding (also called late binding) means the decision about which function to call is made at runtime based on the actual object type, not the pointer or reference type.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Shape {

protected:

string color;

public:

Shape(string c) : color(c) {

cout << "Creating shape: " << color << endl;

}

// Virtual function enables dynamic binding

virtual void draw() {

cout << "Drawing generic shape in " << color << endl;

}

// Non-virtual function uses static binding

void describe() {

cout << "This is a shape" << endl;

}

virtual ~Shape() {

cout << "Destroying shape: " << color << endl;

}

};

class Circle : public Shape {

private:

double radius;

public:

Circle(string c, double r) : Shape(c), radius(r) {

cout << "Creating circle with radius: " << radius << endl;

}

void draw() override {

cout << "Drawing circle (radius " << radius

<< ") in " << color << endl;

}

void describe() { // Hides base class function (not override)

cout << "This is a circle" << endl;

}

~Circle() {

cout << "Destroying circle" << endl;

}

};

class Rectangle : public Shape {

private:

double width, height;

public:

Rectangle(string c, double w, double h)

: Shape(c), width(w), height(h) {

cout << "Creating rectangle: " << width << "x" << height << endl;

}

void draw() override {

cout << "Drawing rectangle (" << width << "x" << height

<< ") in " << color << endl;

}

~Rectangle() {

cout << "Destroying rectangle" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Creating objects ===" << endl;

Shape* shape1 = new Circle("red", 5.0);

Shape* shape2 = new Rectangle("blue", 4.0, 6.0);

cout << "\n=== Dynamic binding with virtual function ===" << endl;

shape1->draw(); // Calls Circle::draw() - runtime decision

shape2->draw(); // Calls Rectangle::draw() - runtime decision

cout << "\n=== Static binding with non-virtual function ===" << endl;

shape1->describe(); // Calls Shape::describe() - compile-time decision

shape2->describe(); // Calls Shape::describe() - compile-time decision

cout << "\n=== Deleting objects ===" << endl;

delete shape1;

delete shape2;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Shape base class: Contains both virtual (draw) and non-virtual (describe) functions

- Circle and Rectangle: Both override the virtual draw() function

- Object creation: We create Circle and Rectangle objects but store them in Shape pointers

- Dynamic binding for draw(): When we call shape1->draw() and shape2->draw(), the program checks the actual object type at runtime

- Runtime type lookup: The program sees shape1 points to a Circle object and calls Circle::draw()

- Static binding for describe(): Since describe() is not virtual, the compiler uses the pointer type (Shape*) to determine which version to call

- Always calls base version: Both shape1->describe() and shape2->describe() call Shape::describe(), even though Circle has its own version

- Virtual destructor: When we delete the pointers, the virtual destructor ensures both derived and base destructors are called

Output:

=== Creating objects ===

Creating shape: red

Creating circle with radius: 5

Creating shape: blue

Creating rectangle: 4x6

=== Dynamic binding with virtual function ===

Drawing circle (radius 5) in red

Drawing rectangle (4x6) in blue

=== Static binding with non-virtual function ===

This is a shape

This is a shape

=== Deleting objects ===

Destroying circle

Destroying shape: red

Destroying rectangle

Destroying shape: blueVirtual Tables (vtables): The Mechanism Behind the Magic

When you use virtual functions, C++ implements dynamic binding using virtual tables (vtables). Understanding this mechanism helps you appreciate the power and cost of polymorphism.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base {

public:

int baseData;

Base() : baseData(100) {}

virtual void func1() {

cout << "Base::func1()" << endl;

}

virtual void func2() {

cout << "Base::func2()" << endl;

}

void nonVirtualFunc() {

cout << "Base::nonVirtualFunc()" << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

int derivedData;

Derived() : derivedData(200) {}

void func1() override {

cout << "Derived::func1()" << endl;

}

// func2 not overridden - uses Base version

void nonVirtualFunc() {

cout << "Derived::nonVirtualFunc()" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "Size of Base: " << sizeof(Base) << " bytes" << endl;

cout << "Size of Derived: " << sizeof(Derived) << " bytes" << endl;

cout << "Size of int: " << sizeof(int) << " bytes" << endl;

cout << "Size of void*: " << sizeof(void*) << " bytes" << endl;

cout << "\n=== Using Base pointer with Derived object ===" << endl;

Base* ptr = new Derived();

ptr->func1(); // Calls Derived::func1() via vtable

ptr->func2(); // Calls Base::func2() via vtable

ptr->nonVirtualFunc(); // Calls Base::nonVirtualFunc() - no vtable lookup

delete ptr;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Virtual functions in Base: func1() and func2() are virtual, triggering vtable creation

- Hidden vptr: Each object with virtual functions contains a hidden pointer (vptr) to its class’s vtable

- Size increase: sizeof(Base) includes baseData (4 bytes) plus vptr (typically 8 bytes on 64-bit systems) = 12-16 bytes (with alignment)

- Derived class size: Includes Base’s data + vptr + derivedData

- Vtable for Base: Contains pointers to Base::func1 and Base::func2

- Vtable for Derived: Contains pointer to Derived::func1 and Base::func2 (inherited)

- Runtime lookup: When calling ptr->func1(), the program follows the vptr to the vtable, then calls the function pointer found there

- Override detection: Since Derived overrides func1(), its vtable points to Derived::func1

- Non-virtual function: nonVirtualFunc() is called directly without vtable lookup, always using the pointer type’s version

Typical output:

Size of Base: 16 bytes

Size of Derived: 24 bytes

Size of int: 4 bytes

Size of void*: 8 bytes

=== Using Base pointer with Derived object ===

Derived::func1()

Base::func2()

Base::nonVirtualFunc()Conceptual vtable structure:

Base vtable:

[0] -> Base::func1

[1] -> Base::func2

Derived vtable:

[0] -> Derived::func1

[1] -> Base::func2Pure Virtual Functions and Abstract Classes

Pure virtual functions have no implementation in the base class and must be overridden by derived classes. Classes with pure virtual functions are abstract and cannot be instantiated.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <cmath>

using namespace std;

// Abstract base class - cannot be instantiated

class Shape {

protected:

string name;

string color;

public:

Shape(string n, string c) : name(n), color(c) {}

// Pure virtual functions (= 0 makes them pure)

virtual double getArea() = 0;

virtual double getPerimeter() = 0;

virtual void draw() = 0;

// Regular virtual function (has implementation)

virtual void displayInfo() {

cout << "Shape: " << name << endl;

cout << "Color: " << color << endl;

cout << "Area: " << getArea() << endl;

cout << "Perimeter: " << getPerimeter() << endl;

}

virtual ~Shape() {}

};

class Circle : public Shape {

private:

double radius;

public:

Circle(string c, double r) : Shape("Circle", c), radius(r) {}

// Must implement all pure virtual functions

double getArea() override {

return 3.14159 * radius * radius;

}

double getPerimeter() override {

return 2 * 3.14159 * radius;

}

void draw() override {

cout << "Drawing a " << color << " circle with radius "

<< radius << endl;

}

};

class Rectangle : public Shape {

private:

double width, height;

public:

Rectangle(string c, double w, double h)

: Shape("Rectangle", c), width(w), height(h) {}

double getArea() override {

return width * height;

}

double getPerimeter() override {

return 2 * (width + height);

}

void draw() override {

cout << "Drawing a " << color << " rectangle "

<< width << "x" << height << endl;

}

};

class Triangle : public Shape {

private:

double side1, side2, side3;

public:

Triangle(string c, double s1, double s2, double s3)

: Shape("Triangle", c), side1(s1), side2(s2), side3(s3) {}

double getArea() override {

// Using Heron's formula

double s = (side1 + side2 + side3) / 2.0;

return sqrt(s * (s - side1) * (s - side2) * (s - side3));

}

double getPerimeter() override {

return side1 + side2 + side3;

}

void draw() override {

cout << "Drawing a " << color << " triangle" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

// Shape shape("test", "red"); // Error! Cannot instantiate abstract class

// Create array of Shape pointers

Shape* shapes[3];

shapes[0] = new Circle("red", 5.0);

shapes[1] = new Rectangle("blue", 4.0, 6.0);

shapes[2] = new Triangle("green", 3.0, 4.0, 5.0);

cout << "=== Processing all shapes polymorphically ===" << endl;

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

shapes[i]->draw();

shapes[i]->displayInfo();

cout << endl;

}

// Clean up

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

delete shapes[i];

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Abstract Shape class: Contains three pure virtual functions marked with

= 0 - Cannot instantiate: You cannot create a Shape object directly because it has pure virtual functions

- Interface definition: Shape defines the interface that all concrete shapes must implement

- Concrete classes: Circle, Rectangle, and Triangle provide implementations for all pure virtual functions

- Must implement all: Each derived class must implement getArea(), getPerimeter(), and draw() or remain abstract

- Can have regular virtuals: displayInfo() is a regular virtual function with a default implementation

- Polymorphic array: We create an array of Shape pointers that can hold any shape type

- Runtime polymorphism: When we call draw() and displayInfo(), the correct version executes based on actual object type

- displayInfo calls pure virtuals: Even though displayInfo() is defined in Shape, when it calls getArea() and getPerimeter(), it uses the derived class implementations

- Cleanup: Deleting through base class pointers works correctly thanks to the virtual destructor

Real-World Application: Payment Processing System

Let’s build a comprehensive payment processing system demonstrating polymorphism in action:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

// Abstract base class for payment methods

class PaymentMethod {

protected:

string accountHolder;

double transactionFee;

public:

PaymentMethod(string holder, double fee)

: accountHolder(holder), transactionFee(fee) {}

// Pure virtual functions - must be implemented

virtual bool processPayment(double amount) = 0;

virtual string getPaymentType() = 0;

virtual void displayDetails() = 0;

// Regular virtual function with default implementation

virtual double calculateTotalCost(double amount) {

return amount + transactionFee;

}

virtual ~PaymentMethod() {

cout << "Payment method destroyed for " << accountHolder << endl;

}

};

class CreditCard : public PaymentMethod {

private:

string cardNumber;

string expiryDate;

double creditLimit;

double currentBalance;

public:

CreditCard(string holder, string cardNum, string expiry, double limit)

: PaymentMethod(holder, 0.029), // 2.9% transaction fee

cardNumber(cardNum), expiryDate(expiry),

creditLimit(limit), currentBalance(0) {}

bool processPayment(double amount) override {

double totalCost = calculateTotalCost(amount);

if (currentBalance + totalCost > creditLimit) {

cout << "Transaction declined - would exceed credit limit" << endl;

return false;

}

currentBalance += totalCost;

cout << "Credit card payment processed: $" << amount << endl;

cout << "Transaction fee: $" << transactionFee << endl;

cout << "Total charged: $" << totalCost << endl;

return true;

}

string getPaymentType() override {

return "Credit Card";

}

void displayDetails() override {

cout << "Payment Type: " << getPaymentType() << endl;

cout << "Account Holder: " << accountHolder << endl;

cout << "Card Number: ****" << cardNumber.substr(cardNumber.length() - 4) << endl;

cout << "Expiry: " << expiryDate << endl;

cout << "Credit Limit: $" << creditLimit << endl;

cout << "Current Balance: $" << currentBalance << endl;

}

};

class DebitCard : public PaymentMethod {

private:

string accountNumber;

double accountBalance;

public:

DebitCard(string holder, string accNum, double balance)

: PaymentMethod(holder, 1.50), // Fixed $1.50 fee

accountNumber(accNum), accountBalance(balance) {}

bool processPayment(double amount) override {

double totalCost = calculateTotalCost(amount);

if (totalCost > accountBalance) {

cout << "Transaction declined - insufficient funds" << endl;

return false;

}

accountBalance -= totalCost;

cout << "Debit card payment processed: $" << amount << endl;

cout << "Transaction fee: $" << transactionFee << endl;

cout << "Remaining balance: $" << accountBalance << endl;

return true;

}

string getPaymentType() override {

return "Debit Card";

}

void displayDetails() override {

cout << "Payment Type: " << getPaymentType() << endl;

cout << "Account Holder: " << accountHolder << endl;

cout << "Account Number: ****" << accountNumber.substr(accountNumber.length() - 4) << endl;

cout << "Available Balance: $" << accountBalance << endl;

}

};

class PayPal : public PaymentMethod {

private:

string email;

double walletBalance;

public:

PayPal(string holder, string emailAddr, double balance)

: PaymentMethod(holder, 0.0), // No transaction fee

email(emailAddr), walletBalance(balance) {}

bool processPayment(double amount) override {

if (amount > walletBalance) {

cout << "Transaction declined - insufficient PayPal balance" << endl;

return false;

}

walletBalance -= amount;

cout << "PayPal payment processed: $" << amount << endl;

cout << "No transaction fee (PayPal promotion!)" << endl;

cout << "Remaining balance: $" << walletBalance << endl;

return true;

}

string getPaymentType() override {

return "PayPal";

}

void displayDetails() override {

cout << "Payment Type: " << getPaymentType() << endl;

cout << "Account Holder: " << accountHolder << endl;

cout << "Email: " << email << endl;

cout << "Wallet Balance: $" << walletBalance << endl;

}

};

class Cryptocurrency : public PaymentMethod {

private:

string walletAddress;

double coinBalance;

double exchangeRate; // USD per coin

public:

Cryptocurrency(string holder, string wallet, double balance, double rate)

: PaymentMethod(holder, 0.005), // 0.5% network fee

walletAddress(wallet), coinBalance(balance), exchangeRate(rate) {}

bool processPayment(double amount) override {

double coinsNeeded = amount / exchangeRate;

double feeInCoins = coinsNeeded * transactionFee;

double totalCoins = coinsNeeded + feeInCoins;

if (totalCoins > coinBalance) {

cout << "Transaction declined - insufficient cryptocurrency" << endl;

return false;

}

coinBalance -= totalCoins;

cout << "Cryptocurrency payment processed: $" << amount << endl;

cout << "Coins spent: " << coinsNeeded << endl;

cout << "Network fee: " << feeInCoins << " coins" << endl;

cout << "Remaining balance: " << coinBalance << " coins ($"

<< (coinBalance * exchangeRate) << ")" << endl;

return true;

}

string getPaymentType() override {

return "Cryptocurrency";

}

void displayDetails() override {

cout << "Payment Type: " << getPaymentType() << endl;

cout << "Account Holder: " << accountHolder << endl;

cout << "Wallet: " << walletAddress.substr(0, 10) << "..." << endl;

cout << "Balance: " << coinBalance << " coins ($"

<< (coinBalance * exchangeRate) << ")" << endl;

cout << "Exchange Rate: $" << exchangeRate << " per coin" << endl;

}

};

// Shopping cart that works with any payment method

class ShoppingCart {

private:

vector<double> items;

public:

void addItem(double price) {

items.push_back(price);

cout << "Item added: $" << price << endl;

}

double getTotal() {

double total = 0;

for (double price : items) {

total += price;

}

return total;

}

// Polymorphic checkout - works with any PaymentMethod

bool checkout(PaymentMethod* payment) {

double total = getTotal();

cout << "\n=== Checkout Process ===" << endl;

cout << "Cart total: $" << total << endl;

cout << "Payment method: " << payment->getPaymentType() << endl;

bool success = payment->processPayment(total);

if (success) {

cout << "Thank you for your purchase!" << endl;

items.clear();

} else {

cout << "Payment failed. Please try another method." << endl;

}

return success;

}

};

int main() {

// Create different payment methods

PaymentMethod* methods[4];

methods[0] = new CreditCard("John Smith", "1234567890123456", "12/25", 5000);

methods[1] = new DebitCard("Jane Doe", "9876543210", 500);

methods[2] = new PayPal("Bob Johnson", "bob@email.com", 300);

methods[3] = new Cryptocurrency("Alice Chen", "1A2B3C4D5E", 2.5, 50000);

// Display all payment methods

cout << "=== Available Payment Methods ===" << endl;

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

methods[i]->displayDetails();

cout << "---" << endl;

}

// Create shopping cart

ShoppingCart cart;

cart.addItem(99.99);

cart.addItem(149.99);

cart.addItem(79.99);

// Try checkout with different payment methods

cout << "\n=== Attempt 1: PayPal ===" << endl;

if (!cart.checkout(methods[2])) {

cout << "\n=== Attempt 2: Debit Card ===" << endl;

if (!cart.checkout(methods[1])) {

cout << "\n=== Attempt 3: Credit Card ===" << endl;

cart.checkout(methods[0]);

}

}

// Clean up

cout << "\n=== Cleanup ===" << endl;

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

delete methods[i];

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Abstract PaymentMethod class: Defines the interface for all payment types with pure virtual functions

- Protected members: accountHolder and transactionFee are accessible to derived classes

- Pure virtual functions: processPayment(), getPaymentType(), and displayDetails() must be implemented by all payment types

- Regular virtual function: calculateTotalCost() has a default implementation but can be overridden

- CreditCard class: Implements payment processing with credit limit checking and balance tracking

- DebitCard class: Implements payment with account balance checking

- PayPal class: Implements payment with wallet balance, no transaction fee

- Cryptocurrency class: Implements payment with coin conversion and network fees

- Each class customizes: Each payment method has its own data members and processing logic

- ShoppingCart class: The checkout method accepts any PaymentMethod pointer—this is polymorphism in action

- Polymorphic checkout: The same checkout code works with credit cards, debit cards, PayPal, and cryptocurrency

- Runtime behavior: When calling payment->processPayment(), the actual method executed depends on the object type

- Flexible payment: The shopping cart doesn’t need to know about specific payment types—it just uses the PaymentMethod interface

- Easy extension: Adding a new payment method (like Apple Pay) requires creating a new class; no changes to ShoppingCart needed

Comparison Table: Virtual vs Non-Virtual Functions

| Aspect | Virtual Functions | Non-Virtual Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Binding | Dynamic (runtime) | Static (compile-time) |

| Performance | Slight overhead (vtable lookup) | Direct function call (faster) |

| Overriding | Can be overridden in derived classes | Cannot be overridden (can be hidden) |

| Polymorphic behavior | Calls based on actual object type | Calls based on pointer/reference type |

| Memory overhead | Adds vptr to objects | No additional memory |

| Use case | When derived classes need different behavior | When behavior is fixed for all classes |

| Pure virtual | Can be pure (= 0) | Cannot be pure |

Common Polymorphism Patterns

Pattern 1: Factory Pattern with Polymorphism

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Logger {

public:

virtual void log(string message) = 0;

virtual ~Logger() {}

};

class FileLogger : public Logger {

public:

void log(string message) override {

cout << "[FILE] " << message << endl;

// In real implementation, write to file

}

};

class ConsoleLogger : public Logger {

public:

void log(string message) override {

cout << "[CONSOLE] " << message << endl;

}

};

class DatabaseLogger : public Logger {

public:

void log(string message) override {

cout << "[DATABASE] " << message << endl;

// In real implementation, write to database

}

};

// Factory function returns base class pointer

Logger* createLogger(string type) {

if (type == "file") {

return new FileLogger();

} else if (type == "console") {

return new ConsoleLogger();

} else if (type == "database") {

return new DatabaseLogger();

}

return nullptr;

}

int main() {

Logger* logger = createLogger("console");

if (logger) {

logger->log("Application started");

logger->log("Processing data...");

logger->log("Application finished");

delete logger;

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Abstract Logger interface: Defines the log() pure virtual function

- Concrete loggers: FileLogger, ConsoleLogger, and DatabaseLogger implement different logging strategies

- Factory function: createLogger() returns a Logger pointer to the appropriate concrete type

- Client code independence: The main function doesn’t know which logger type it’s using

- Runtime selection: The logger type is determined at runtime based on the string parameter

- Polymorphic usage: The logger pointer works with any logger type through the common interface

- Easy switching: Changing from console to file logging requires changing only one parameter

This pattern is incredibly powerful for creating flexible, configurable systems.

Pattern 2: Strategy Pattern

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

// Abstract strategy for sorting

class SortStrategy {

public:

virtual void sort(vector<int>& data) = 0;

virtual string getName() = 0;

virtual ~SortStrategy() {}

};

class BubbleSort : public SortStrategy {

public:

void sort(vector<int>& data) override {

cout << "Sorting with Bubble Sort" << endl;

int n = data.size();

for (int i = 0; i < n - 1; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < n - i - 1; j++) {

if (data[j] > data[j + 1]) {

swap(data[j], data[j + 1]);

}

}

}

}

string getName() override {

return "Bubble Sort";

}

};

class QuickSort : public SortStrategy {

public:

void sort(vector<int>& data) override {

cout << "Sorting with Quick Sort" << endl;

quickSortHelper(data, 0, data.size() - 1);

}

string getName() override {

return "Quick Sort";

}

private:

void quickSortHelper(vector<int>& arr, int low, int high) {

if (low < high) {

int pi = partition(arr, low, high);

quickSortHelper(arr, low, pi - 1);

quickSortHelper(arr, pi + 1, high);

}

}

int partition(vector<int>& arr, int low, int high) {

int pivot = arr[high];

int i = low - 1;

for (int j = low; j < high; j++) {

if (arr[j] < pivot) {

i++;

swap(arr[i], arr[j]);

}

}

swap(arr[i + 1], arr[high]);

return i + 1;

}

};

class DataProcessor {

private:

SortStrategy* strategy;

public:

DataProcessor(SortStrategy* s) : strategy(s) {}

void setStrategy(SortStrategy* s) {

strategy = s;

}

void processData(vector<int>& data) {

cout << "Processing with " << strategy->getName() << endl;

strategy->sort(data);

}

};

int main() {

vector<int> data1 = {64, 34, 25, 12, 22, 11, 90};

vector<int> data2 = {5, 2, 8, 1, 9, 3, 7};

BubbleSort bubbleSort;

QuickSort quickSort;

DataProcessor processor(&bubbleSort);

cout << "=== Processing small dataset ===" << endl;

processor.processData(data1);

cout << "\n=== Switching to QuickSort for large dataset ===" << endl;

processor.setStrategy(&quickSort);

processor.processData(data2);

cout << "\nSorted data1: ";

for (int num : data1) cout << num << " ";

cout << "\nSorted data2: ";

for (int num : data2) cout << num << " ";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Abstract SortStrategy: Defines the interface for different sorting algorithms

- Concrete strategies: BubbleSort and QuickSort implement different sorting approaches

- DataProcessor class: Contains a strategy pointer that can be changed at runtime

- setStrategy method: Allows switching the algorithm dynamically

- processData method: Uses whatever strategy is currently set

- Runtime flexibility: We can change from bubble sort to quick sort without modifying DataProcessor

- Polymorphic behavior: The same processData() method works with any sorting strategy

- Algorithm independence: DataProcessor doesn’t need to know how sorting is implemented

Virtual Destructors: A Critical Requirement

When using polymorphism with dynamic memory, you must declare the base class destructor as virtual:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base {

private:

int* data;

public:

Base() {

data = new int[100];

cout << "Base constructor - allocated memory" << endl;

}

// Virtual destructor (CRITICAL!)

virtual ~Base() {

delete[] data;

cout << "Base destructor - freed memory" << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

private:

int* moreData;

public:

Derived() {

moreData = new int[200];

cout << "Derived constructor - allocated more memory" << endl;

}

~Derived() {

delete[] moreData;

cout << "Derived destructor - freed more memory" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Creating Derived object with Base pointer ===" << endl;

Base* ptr = new Derived();

cout << "\n=== Deleting through Base pointer ===" << endl;

delete ptr; // Calls both destructors because Base destructor is virtual

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Base class allocates memory: The Base constructor allocates an array dynamically

- Virtual destructor: Base’s destructor is marked virtual—this is essential

- Derived class allocates more memory: Derived adds its own dynamic allocation

- Derived object creation: We create a Derived object but store it in a Base pointer

- Polymorphic deletion: When we delete through the Base pointer, the virtual destructor mechanism kicks in

- Correct destruction order: First Derived’s destructor runs, then Base’s destructor

- No memory leak: Both allocations are properly freed

Output:

=== Creating Derived object with Base pointer ===

Base constructor - allocated memory

Derived constructor - allocated more memory

=== Deleting through Base pointer ===

Derived destructor - freed more memory

Base destructor - freed memoryWhat happens without virtual destructor:

class BadBase {

public:

~BadBase() { // NOT virtual - DANGER!

cout << "BadBase destructor" << endl;

}

};

class BadDerived : public BadBase {

private:

int* data;

public:

BadDerived() {

data = new int[1000];

}

~BadDerived() {

delete[] data; // Never called! Memory leak!

cout << "BadDerived destructor" << endl;

}

};

// BadBase* ptr = new BadDerived();

// delete ptr; // Only calls BadBase destructor - MEMORY LEAK!Performance Considerations

Polymorphism has a small performance cost due to vtable lookups, but this is rarely significant in practice:

#include <iostream>

#include <chrono>

using namespace std;

class DirectCall {

public:

int compute(int x) {

return x * x + x + 1;

}

};

class VirtualCall {

public:

virtual int compute(int x) {

return x * x + x + 1;

}

};

int main() {

const int ITERATIONS = 100000000;

// Test direct calls

DirectCall direct;

auto start = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

long long sum1 = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < ITERATIONS; i++) {

sum1 += direct.compute(i % 100);

}

auto end = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto duration1 = chrono::duration_cast<chrono::milliseconds>(end - start);

// Test virtual calls

VirtualCall virtualObj;

VirtualCall* ptr = &virtualObj;

start = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

long long sum2 = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < ITERATIONS; i++) {

sum2 += ptr->compute(i % 100);

}

end = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto duration2 = chrono::duration_cast<chrono::milliseconds>(end - start);

cout << "Direct calls: " << duration1.count() << " ms" << endl;

cout << "Virtual calls: " << duration2.count() << " ms" << endl;

cout << "Overhead: " << (duration2.count() - duration1.count()) << " ms" << endl;

cout << "Percentage: " << (100.0 * (duration2.count() - duration1.count()) / duration1.count()) << "%" << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- DirectCall class: Has a regular non-virtual method

- VirtualCall class: Has the same method but marked virtual

- 100 million iterations: We call each version 100 million times to measure the difference

- Timing direct calls: We measure how long non-virtual calls take

- Timing virtual calls: We measure virtual function calls through a pointer

- Calculate overhead: The difference shows the cost of vtable lookups

- Typical results: Virtual calls are usually only 2-5% slower—negligible in most applications

The performance impact is minimal because:

- Modern CPUs have excellent branch prediction

- Vtable lookups are cache-friendly

- The actual function execution time usually dwarfs lookup time

Best Practices for Polymorphism

1. Always Use Virtual Destructors in Base Classes

class Base {

public:

virtual ~Base() {} // Always virtual for polymorphic classes

};2. Use the override Keyword

class Derived : public Base {

public:

void func() override { // Catches signature mismatches

// implementation

}

};3. Prefer Interfaces (Abstract Classes) for Flexibility

class IPlugin {

public:

virtual void initialize() = 0;

virtual void execute() = 0;

virtual void cleanup() = 0;

virtual ~IPlugin() {}

};4. Don’t Call Virtual Functions in Constructors

class Bad {

public:

Bad() {

init(); // Dangerous! Calls Base version even in Derived constructor

}

virtual void init() {

cout << "Base init" << endl;

}

};

class Better {

public:

Better() {

// Don't call virtual functions here

}

void initialize() { // Call this after construction

init();

}

virtual void init() {

cout << "Base init" << endl;

}

};Conclusion: Harnessing the Power of Polymorphism

Polymorphism is the cornerstone of flexible, extensible object-oriented design in C++. Through virtual functions and dynamic binding, you can write code that works with abstractions rather than concrete types, creating systems that adapt to new requirements without modification.

The key concepts to remember:

- Virtual functions enable runtime polymorphism through dynamic binding

- Pure virtual functions create abstract classes that define interfaces

- Virtual destructors are essential when using polymorphism with dynamic memory

- The override keyword prevents subtle bugs and makes code more maintainable

- Vtables enable the magic of polymorphism with minimal performance cost

- Polymorphic patterns like factory and strategy create highly flexible designs

When you use a base class pointer or reference to manipulate derived class objects, you’re leveraging one of C++’s most powerful features. The program automatically selects the correct method at runtime, enabling you to write generic code that works with types that don’t even exist yet.

This is the essence of polymorphism: writing code once that works with many forms. Master this concept, and you’ll create software that’s easier to extend, maintain, and understand—software that follows the Open/Closed Principle, where systems are open for extension but closed for modification.

Polymorphism transforms rigid, repetitive code into elegant, reusable abstractions. It’s the difference between writing separate functions for every type and writing one function that works with all types. This is what makes object-oriented programming in C++ so powerful and why polymorphism remains a fundamental pillar of modern software development.