Encapsulation in C++ is a fundamental object-oriented programming principle that bundles data and methods within a class while restricting direct access to some components using access specifiers (private, public, protected). This data-hiding mechanism protects object integrity, prevents unauthorized modifications, and creates well-defined interfaces for interacting with class functionality.

Introduction: Understanding the Foundation of Secure Code

Encapsulation stands as one of the four pillars of object-oriented programming, alongside inheritance, polymorphism, and abstraction. In C++, encapsulation serves as your first line of defense against bugs, unauthorized data manipulation, and poorly structured code. By controlling how data is accessed and modified, you create robust, maintainable, and secure applications that stand the test of time.

When you write C++ code without proper encapsulation, you expose your program’s internal workings to the outside world. Imagine building a car where anyone could directly access and modify the engine components while driving—chaos would ensue. Encapsulation prevents this chaos in software by establishing clear boundaries between what users of your code can and cannot access.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through every aspect of encapsulation in C++, from basic access specifiers to advanced design patterns. You’ll learn not just the syntax, but the reasoning behind encapsulation principles and how to apply them effectively in real-world scenarios.

What is Encapsulation? The Core Concept Explained

Encapsulation is the practice of bundling related data (member variables) and functions (member methods) into a single unit called a class, while hiding the internal implementation details from external access. This concept creates a protective barrier around your data, ensuring that it can only be accessed or modified through well-defined interfaces.

Think of encapsulation like a capsule in medicine. The active ingredients (data) are enclosed within a protective coating (class), and they’re released only under specific conditions (through public methods). The user of the medicine doesn’t need to know the chemical composition—they just need to know how to take it.

In C++, encapsulation achieves several critical objectives:

Data Protection: By making data members private, you prevent direct manipulation that could leave objects in invalid states. For example, you wouldn’t want a BankAccount object to have a negative balance through direct assignment—you’d want all balance changes to go through validated withdrawal and deposit methods.

Implementation Flexibility: When internal details are hidden, you can change how your class works internally without breaking code that uses your class. You might switch from storing temperature in Fahrenheit to Celsius internally, but external code using your Temperature class wouldn’t need to change.

Controlled Access: Public methods (often called getters and setters) provide controlled access to private data, allowing you to add validation, logging, or any other logic when data is read or modified.

Modularity: Encapsulation creates clear boundaries between different parts of your program, making code easier to understand, test, and maintain.

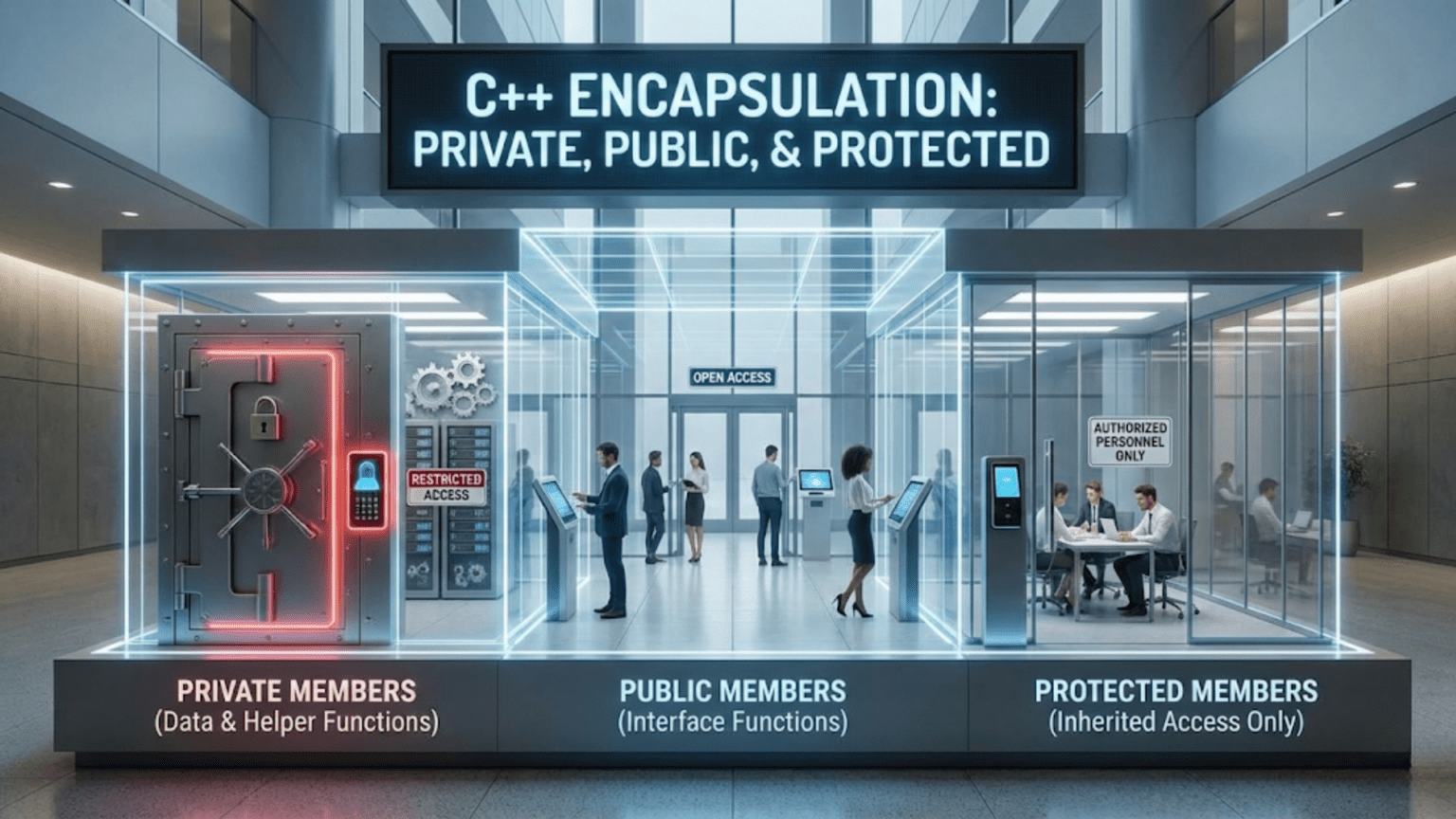

The Three Access Specifiers: Private, Public, and Protected

C++ provides three access specifiers that control the visibility and accessibility of class members. Understanding when and how to use each is essential for effective encapsulation.

Private Members: The Default Protection Level

Private members are accessible only from within the same class. They cannot be accessed directly from outside the class, not even from derived classes. In C++, members declared without any access specifier are private by default in a class.

class BankAccount {

// These are private by default (no specifier needed)

double balance;

string accountNumber;

private: // Explicitly stating private (redundant but clear)

int securityPin;

bool validatePin(int pin) {

return pin == securityPin;

}

public:

BankAccount(string accNum, int pin) {

accountNumber = accNum;

securityPin = pin;

balance = 0.0;

}

void deposit(double amount) {

if (amount > 0) {

balance += amount;

}

}

bool withdraw(double amount, int pin) {

if (validatePin(pin) && amount > 0 && balance >= amount) {

balance -= amount;

return true;

}

return false;

}

double getBalance(int pin) {

if (validatePin(pin)) {

return balance;

}

return -1; // Invalid access

}

};In this example, the balance, accountNumber, and securityPin are private. Users of the BankAccount class cannot directly access or modify these values. They must use the public methods, which include validation logic to ensure the account remains in a valid state.

Public Members: The Class Interface

Public members can be accessed from anywhere in the program where the object is visible. Public members form the interface of your class—the contract between your class and the code that uses it.

class Rectangle {

private:

double width;

double height;

public:

// Constructor - public interface for creating objects

Rectangle(double w, double h) {

setWidth(w);

setHeight(h);

}

// Public setters with validation

void setWidth(double w) {

if (w > 0) {

width = w;

} else {

cout << "Width must be positive!" << endl;

width = 1.0; // Default safe value

}

}

void setHeight(double h) {

if (h > 0) {

height = h;

} else {

cout << "Height must be positive!" << endl;

height = 1.0; // Default safe value

}

}

// Public getters - safe read access

double getWidth() const {

return width;

}

double getHeight() const {

return height;

}

// Public methods for calculations

double calculateArea() const {

return width * height;

}

double calculatePerimeter() const {

return 2 * (width + height);

}

void displayInfo() const {

cout << "Rectangle: " << width << " x " << height << endl;

cout << "Area: " << calculateArea() << endl;

cout << "Perimeter: " << calculatePerimeter() << endl;

}

};The Rectangle class exposes only what’s necessary through its public interface. Users can set dimensions (with validation), retrieve values, and perform calculations, but they cannot accidentally set invalid values or bypass the validation logic.

Protected Members: Inheritance-Friendly Encapsulation

Protected members are accessible within the class itself and by derived classes (through inheritance), but not from outside the class hierarchy. This access level strikes a balance between private (too restrictive for inheritance) and public (too permissive).

class Employee {

protected:

string name;

int employeeId;

double baseSalary;

// Protected method accessible to derived classes

virtual double calculateBonus() {

return baseSalary * 0.1; // 10% default bonus

}

private:

string socialSecurityNumber; // Truly private, even from derived classes

public:

Employee(string n, int id, double salary, string ssn) {

name = n;

employeeId = id;

baseSalary = salary;

socialSecurityNumber = ssn;

}

virtual double calculateTotalCompensation() {

return baseSalary + calculateBonus();

}

void displayInfo() {

cout << "Name: " << name << endl;

cout << "ID: " << employeeId << endl;

cout << "Total Compensation: $" << calculateTotalCompensation() << endl;

}

};

class Manager : public Employee {

private:

int teamSize;

public:

Manager(string n, int id, double salary, string ssn, int team)

: Employee(n, id, salary, ssn) {

teamSize = team;

}

// Override protected method - can access protected members

double calculateBonus() override {

// Managers get bonus based on team size

double teamBonus = teamSize * 1000;

double salaryBonus = baseSalary * 0.15; // 15% of base salary

return teamBonus + salaryBonus;

}

void displayTeamInfo() {

// Can access protected members: name, employeeId, baseSalary

cout << name << " manages " << teamSize << " employees" << endl;

// Cannot access private member socialSecurityNumber

}

};

class SalesEmployee : public Employee {

private:

double salesRevenue;

public:

SalesEmployee(string n, int id, double salary, string ssn, double revenue)

: Employee(n, id, salary, ssn) {

salesRevenue = revenue;

}

// Override protected method

double calculateBonus() override {

// Sales employees get 5% commission on revenue

return salesRevenue * 0.05;

}

double getTotalSales() {

return salesRevenue;

}

};In this inheritance hierarchy, protected members allow derived classes to access and utilize base class data while maintaining encapsulation from external code. The socialSecurityNumber remains truly private, inaccessible even to derived classes, demonstrating how different access levels work together.

Access Specifier Comparison Table

| Access Level | Same Class | Derived Class | Outside Class | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | ✓ Yes | ✗ No | ✗ No | Internal implementation details, sensitive data |

| Protected | ✓ Yes | ✓ Yes | ✗ No | Data shared with derived classes, extensible design |

| Public | ✓ Yes | ✓ Yes | ✓ Yes | Class interface, methods for external interaction |

Why Encapsulation Matters: Real-World Benefits

Understanding the syntax of access specifiers is one thing, but appreciating why encapsulation matters requires looking at real-world scenarios where it prevents problems and enables better design.

Preventing Invalid States

Without encapsulation, objects can end up in invalid or inconsistent states. Consider a Date class:

// Bad design - no encapsulation

class BadDate {

public:

int day;

int month;

int year;

};

int main() {

BadDate date;

date.day = 35; // Invalid! No month has 35 days

date.month = 13; // Invalid! Only 12 months

date.year = -500; // Questionable for modern applications

}With proper encapsulation:

class GoodDate {

private:

int day;

int month;

int year;

bool isValidDate(int d, int m, int y) {

if (m < 1 || m > 12) return false;

if (d < 1) return false;

int daysInMonth[] = {31, 28, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31};

// Check for leap year

if (m == 2 && isLeapYear(y)) {

return d <= 29;

}

return d <= daysInMonth[m - 1];

}

bool isLeapYear(int y) {

return (y % 4 == 0 && y % 100 != 0) || (y % 400 == 0);

}

public:

GoodDate(int d, int m, int y) {

if (isValidDate(d, m, y)) {

day = d;

month = m;

year = y;

} else {

cout << "Invalid date! Setting to default." << endl;

day = 1;

month = 1;

year = 2025;

}

}

void setDate(int d, int m, int y) {

if (isValidDate(d, m, y)) {

day = d;

month = m;

year = y;

} else {

cout << "Invalid date provided. Date not changed." << endl;

}

}

int getDay() const { return day; }

int getMonth() const { return month; }

int getYear() const { return year; }

void displayDate() const {

cout << day << "/" << month << "/" << year << endl;

}

};Now it’s impossible to create an invalid date. The validation logic in the constructor and setter ensures that the object always maintains a valid state.

Enabling Implementation Changes

Encapsulation allows you to change internal implementation without affecting code that uses your class. This is crucial for software maintenance and evolution.

// Version 1: Store temperature in Celsius

class Temperature_V1 {

private:

double celsius;

public:

Temperature_V1(double c) : celsius(c) {}

double getCelsius() const {

return celsius;

}

double getFahrenheit() const {

return celsius * 9.0 / 5.0 + 32.0;

}

double getKelvin() const {

return celsius + 273.15;

}

void setCelsius(double c) {

celsius = c;

}

};

// Version 2: Store temperature in Kelvin (scientific accuracy)

class Temperature_V2 {

private:

double kelvin; // Changed internal representation

public:

Temperature_V2(double c) : kelvin(c + 273.15) {}

double getCelsius() const {

return kelvin - 273.15; // Converted on demand

}

double getFahrenheit() const {

return (kelvin - 273.15) * 9.0 / 5.0 + 32.0;

}

double getKelvin() const {

return kelvin;

}

void setCelsius(double c) {

kelvin = c + 273.15; // Converted when set

}

};Both versions provide identical public interfaces. Code using either version works identically, even though the internal storage changed completely. This is the power of encapsulation—the ability to refactor and improve without breaking existing code.

Simplifying Complex Systems

Encapsulation hides complexity, presenting users with only what they need to know. Consider a complex database connection class:

class DatabaseConnection {

private:

string connectionString;

void* connectionHandle; // Internal connection object

bool isConnected;

int retryCount;

int maxRetries;

// Complex internal methods

bool establishConnection() {

// Complex connection logic

// Handle authentication, encryption, connection pooling

cout << "Establishing connection..." << endl;

// Simulated connection

isConnected = true;

return true;

}

void closeConnection() {

if (isConnected) {

cout << "Closing connection..." << endl;

isConnected = false;

}

}

bool retryConnection() {

for (int i = 0; i < maxRetries; i++) {

cout << "Retry attempt " << (i + 1) << "..." << endl;

if (establishConnection()) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

void logError(const string& error) {

cout << "Error: " << error << endl;

// In real implementation, write to log file

}

public:

DatabaseConnection(string connStr, int maxRetry = 3)

: connectionString(connStr), maxRetries(maxRetry),

isConnected(false), retryCount(0), connectionHandle(nullptr) {

}

// Simple public interface

bool connect() {

if (isConnected) {

return true;

}

if (!establishConnection()) {

return retryConnection();

}

return true;

}

void disconnect() {

closeConnection();

}

bool executeQuery(const string& query) {

if (!isConnected) {

logError("Not connected to database");

return false;

}

cout << "Executing query: " << query << endl;

// Complex query execution logic hidden here

return true;

}

bool getConnectionStatus() const {

return isConnected;

}

~DatabaseConnection() {

disconnect();

}

};Users of this class only interact with simple methods like connect(), disconnect(), and executeQuery(). All the complexity of connection handling, retries, error logging, and resource management is hidden behind the public interface.

Getters and Setters: The Gateway to Encapsulated Data

Getters (accessor methods) and setters (mutator methods) are the standard way to provide controlled access to private data members. While they might seem like simple pass-through functions, they offer significant advantages.

Basic Getter and Setter Implementation

class Student {

private:

string name;

int age;

double gpa;

public:

// Getters (const to indicate they don't modify object)

string getName() const {

return name;

}

int getAge() const {

return age;

}

double getGPA() const {

return gpa;

}

// Setters with validation

void setName(const string& n) {

if (!n.empty()) {

name = n;

} else {

cout << "Name cannot be empty!" << endl;

}

}

void setAge(int a) {

if (a >= 0 && a <= 120) {

age = a;

} else {

cout << "Invalid age!" << endl;

}

}

void setGPA(double g) {

if (g >= 0.0 && g <= 4.0) {

gpa = g;

} else {

cout << "GPA must be between 0.0 and 4.0!" << endl;

}

}

};Advanced Getter and Setter Patterns

Getters and setters can do much more than simple validation. Here are advanced patterns:

class SmartAccount {

private:

double balance;

vector<string> transactionLog;

time_t lastAccessTime;

int accessCount;

bool isLocked;

public:

SmartAccount() : balance(0.0), accessCount(0), isLocked(false) {

lastAccessTime = time(nullptr);

}

// Getter with logging and access tracking

double getBalance() {

accessCount++;

lastAccessTime = time(nullptr);

if (accessCount % 10 == 0) {

cout << "Balance accessed " << accessCount << " times." << endl;

}

return balance;

}

// Setter with transaction logging

bool setBalance(double newBalance, const string& reason) {

if (isLocked) {

cout << "Account is locked!" << endl;

return false;

}

// Log the transaction

string logEntry = "Balance changed from " + to_string(balance) +

" to " + to_string(newBalance) +

". Reason: " + reason;

transactionLog.push_back(logEntry);

balance = newBalance;

return true;

}

// Computed getter (doesn't correspond to a stored value)

double getBalanceWithInterest(double interestRate) const {

return balance * (1 + interestRate);

}

// Method to view transaction history

void displayTransactionLog() const {

cout << "Transaction History:" << endl;

for (const auto& entry : transactionLog) {

cout << "- " << entry << endl;

}

}

// Security methods

void lockAccount() {

isLocked = true;

transactionLog.push_back("Account locked");

}

void unlockAccount() {

isLocked = false;

transactionLog.push_back("Account unlocked");

}

};This demonstrates how getters and setters can incorporate business logic, security measures, logging, and computation—far beyond simple data access.

When to Use Getters and Setters

Not every private member needs getters and setters. Here are guidelines:

Always provide getters for:

- Data that external code needs to read

- Computed values derived from private data

- Status information about the object’s state

Provide setters only when:

- External code legitimately needs to modify the value

- You can validate the new value

- The modification represents a meaningful operation

Avoid setters for:

- Values that should only be set during construction

- Data that changes automatically based on other operations

- Internal state that should be modified only through specific methods

class Circle {

private:

double radius;

static const double PI;

public:

Circle(double r) : radius(r > 0 ? r : 1.0) {}

// Getter for radius - external code might need this

double getRadius() const {

return radius;

}

// Setter for radius with validation

void setRadius(double r) {

if (r > 0) {

radius = r;

}

}

// Computed getters - no setters needed

double getArea() const {

return PI * radius * radius;

}

double getCircumference() const {

return 2 * PI * radius;

}

double getDiameter() const {

return 2 * radius;

}

// No getter or setter for PI - it's a constant

};

const double Circle::PI = 3.14159265359;Constructor Initialization and Encapsulation

Constructors play a crucial role in encapsulation by ensuring objects start in a valid state. Proper constructor design is essential for maintaining encapsulated integrity.

Constructor Initialization Lists

Member initializer lists are the preferred way to initialize private members because they initialize members before the constructor body executes, which is more efficient and necessary for const members and references.

class Person {

private:

const string birthCity; // const member - must use initializer list

string currentCity;

int age;

string& nameReference; // reference member - must use initializer list

public:

// Using initializer list (efficient and necessary for const/reference)

Person(const string& birth, const string& current, int a, string& nameRef)

: birthCity(birth), currentCity(current), age(a), nameReference(nameRef) {

// Constructor body for additional logic

if (age < 0) {

age = 0;

}

}

// Getter methods

string getBirthCity() const { return birthCity; }

string getCurrentCity() const { return currentCity; }

int getAge() const { return age; }

// Setter for changeable data only

void setCurrentCity(const string& city) {

currentCity = city;

}

void celebrateBirthday() {

age++;

}

};Multiple Constructors with Delegation

C++ allows constructor delegation, where one constructor calls another to avoid code duplication:

class BankAccount {

private:

string accountNumber;

string ownerName;

double balance;

double interestRate;

public:

// Primary constructor with full initialization

BankAccount(string accNum, string owner, double initialBalance, double rate)

: accountNumber(accNum), ownerName(owner), balance(initialBalance),

interestRate(rate) {

cout << "Account created for " << ownerName << endl;

}

// Delegating constructor with default interest rate

BankAccount(string accNum, string owner, double initialBalance)

: BankAccount(accNum, owner, initialBalance, 0.02) {

// Delegates to primary constructor with 2% default rate

}

// Delegating constructor with default balance and rate

BankAccount(string accNum, string owner)

: BankAccount(accNum, owner, 0.0, 0.02) {

// Delegates to primary constructor with defaults

}

void displayInfo() const {

cout << "Account: " << accountNumber << endl;

cout << "Owner: " << ownerName << endl;

cout << "Balance: $" << balance << endl;

cout << "Interest Rate: " << (interestRate * 100) << "%" << endl;

}

};Preventing Invalid Construction

Sometimes you want to prevent construction with certain parameters. You can make constructors private and provide factory methods:

class Configuration {

private:

map<string, string> settings;

// Private constructor - can't be called directly

Configuration() {}

// Private constructor for internal use

Configuration(const map<string, string>& initialSettings)

: settings(initialSettings) {}

public:

// Factory method for creating from file

static Configuration* createFromFile(const string& filename) {

map<string, string> loadedSettings;

// Simulated file loading

cout << "Loading configuration from " << filename << endl;

loadedSettings["theme"] = "dark";

loadedSettings["language"] = "en";

// Return a properly initialized Configuration

return new Configuration(loadedSettings);

}

// Factory method for creating with defaults

static Configuration* createDefault() {

map<string, string> defaults;

defaults["theme"] = "light";

defaults["language"] = "en";

defaults["notifications"] = "enabled";

return new Configuration(defaults);

}

string getSetting(const string& key) const {

auto it = settings.find(key);

if (it != settings.end()) {

return it->second;

}

return "";

}

void setSetting(const string& key, const string& value) {

settings[key] = value;

}

};

int main() {

// Configuration config; // Error: constructor is private

Configuration* config1 = Configuration::createFromFile("config.ini");

Configuration* config2 = Configuration::createDefault();

cout << "Theme: " << config1->getSetting("theme") << endl;

delete config1;

delete config2;

}Const Correctness and Encapsulation

Const correctness is a powerful aspect of C++ encapsulation that helps prevent accidental modifications and clearly communicates intent in your code.

Const Member Functions

When a member function doesn’t modify the object’s state, mark it as const. This allows the function to be called on const objects and signals to users that the function is safe for reading data.

class Point3D {

private:

double x, y, z;

public:

Point3D(double x_val, double y_val, double z_val)

: x(x_val), y(y_val), z(z_val) {}

// Const member functions - promise not to modify object

double getX() const { return x; }

double getY() const { return y; }

double getZ() const { return z; }

double distanceFromOrigin() const {

return sqrt(x*x + y*y + z*z);

}

void display() const {

cout << "(" << x << ", " << y << ", " << z << ")" << endl;

}

// Non-const member functions - modify object state

void setX(double val) { x = val; }

void setY(double val) { y = val; }

void setZ(double val) { z = val; }

void scale(double factor) {

x *= factor;

y *= factor;

z *= factor;

}

};

void printPoint(const Point3D& point) {

// Can only call const member functions on const parameter

point.display(); // OK - display() is const

cout << "Distance: " << point.distanceFromOrigin() << endl; // OK

// point.scale(2.0); // Error: scale() is not const

}Mutable Members

Sometimes you need to modify a member even in const functions (for caching, logging, etc.). The mutable keyword allows this:

class ExpensiveCalculation {

private:

double value;

mutable double cachedResult;

mutable bool cacheValid;

mutable int calculationCount;

public:

ExpensiveCalculation(double v)

: value(v), cachedResult(0.0), cacheValid(false), calculationCount(0) {}

// Const function that modifies mutable members

double getExpensiveResult() const {

calculationCount++; // Can modify mutable member

if (cacheValid) {

cout << "Returning cached result" << endl;

return cachedResult;

}

cout << "Performing expensive calculation..." << endl;

// Simulate expensive operation

cachedResult = value * value * value +

2 * value * value + value + 1;

cacheValid = true;

return cachedResult;

}

void setValue(double v) {

value = v;

cacheValid = false; // Invalidate cache

}

int getCalculationCount() const {

return calculationCount;

}

};Friend Functions and Classes: Controlled Encapsulation Breaking

Sometimes you need to grant specific external functions or classes access to private members. The friend keyword does this while maintaining controlled access.

Friend Functions

Friend functions can access private members but aren’t member functions themselves:

class Complex {

private:

double real;

double imag;

public:

Complex(double r = 0, double i = 0) : real(r), imag(i) {}

// Getters

double getReal() const { return real; }

double getImag() const { return imag; }

// Friend function declaration

friend Complex operator+(const Complex& c1, const Complex& c2);

friend ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Complex& c);

};

// Friend function definition - can access private members

Complex operator+(const Complex& c1, const Complex& c2) {

return Complex(c1.real + c2.real, c1.imag + c2.imag);

}

ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Complex& c) {

os << c.real;

if (c.imag >= 0) {

os << "+" << c.imag << "i";

} else {

os << c.imag << "i";

}

return os;

}

int main() {

Complex c1(3, 4);

Complex c2(1, 2);

Complex c3 = c1 + c2; // Uses friend operator+

cout << "c1 = " << c1 << endl; // Uses friend operator<<

cout << "c2 = " << c2 << endl;

cout << "c3 = " << c3 << endl;

}Friend Classes

An entire class can be declared as a friend, granting it access to private members:

class Engine {

private:

int horsepower;

double fuelEfficiency;

bool isRunning;

// Private diagnostic methods

void runDiagnostics() {

cout << "Running engine diagnostics..." << endl;

}

public:

Engine(int hp, double efficiency)

: horsepower(hp), fuelEfficiency(efficiency), isRunning(false) {}

void start() {

isRunning = true;

cout << "Engine started" << endl;

}

void stop() {

isRunning = false;

cout << "Engine stopped" << endl;

}

// Declare CarManufacturer as friend

friend class CarManufacturer;

};

class CarManufacturer {

private:

string companyName;

public:

CarManufacturer(string name) : companyName(name) {}

// Can access all private members of Engine

void inspectEngine(Engine& engine) {

cout << companyName << " inspecting engine:" << endl;

cout << "Horsepower: " << engine.horsepower << endl;

cout << "Fuel Efficiency: " << engine.fuelEfficiency << endl;

cout << "Running: " << (engine.isRunning ? "Yes" : "No") << endl;

// Can call private methods

engine.runDiagnostics();

}

void modifyEngine(Engine& engine, int newHorsepower) {

cout << companyName << " modifying engine specifications" << endl;

engine.horsepower = newHorsepower;

}

};Use friend declarations sparingly—they break encapsulation and should only be used when there’s a compelling design reason, such as operator overloading or tightly coupled classes that genuinely need intimate access to each other’s internals.

Encapsulation in Inheritance Hierarchies

When working with inheritance, access specifiers become more nuanced. The protected access level becomes particularly important for creating extensible class hierarchies.

Protected Members for Inheritance

Protected members provide a middle ground—hidden from external code but available to derived classes:

class Vehicle {

protected:

string manufacturer;

int year;

double maxSpeed;

// Protected helper method

void displayBasicInfo() const {

cout << year << " " << manufacturer << endl;

cout << "Max Speed: " << maxSpeed << " mph" << endl;

}

private:

string vinNumber; // Truly private - not accessible to derived classes

public:

Vehicle(string mfr, int yr, double speed, string vin)

: manufacturer(mfr), year(yr), maxSpeed(speed), vinNumber(vin) {}

virtual void displayInfo() const {

displayBasicInfo();

cout << "VIN: " << vinNumber << endl;

}

string getVIN() const {

return vinNumber;

}

};

class Car : public Vehicle {

private:

int numDoors;

string bodyStyle;

public:

Car(string mfr, int yr, double speed, string vin, int doors, string style)

: Vehicle(mfr, yr, speed, vin), numDoors(doors), bodyStyle(style) {}

void displayInfo() const override {

// Can access protected members from base class

cout << "=== Car Information ===" << endl;

displayBasicInfo(); // Protected method from Vehicle

// Can access protected data

cout << "Manufacturer from protected: " << manufacturer << endl;

// Cannot access private members

// cout << vinNumber << endl; // Error!

// Must use public interface for private data

cout << "VIN: " << getVIN() << endl;

cout << "Doors: " << numDoors << endl;

cout << "Body Style: " << bodyStyle << endl;

}

};Inheritance Access Specifiers

When inheriting, you specify whether the inheritance is public, protected, or private, which affects how base class members are accessible in derived classes:

class Base {

public:

int publicMember;

protected:

int protectedMember;

private:

int privateMember;

public:

Base() : publicMember(1), protectedMember(2), privateMember(3) {}

};

// Public inheritance (most common)

class PublicDerived : public Base {

void accessMembers() {

publicMember = 10; // public remains public

protectedMember = 20; // protected remains protected

// privateMember = 30; // Error: private not accessible

}

};

// Protected inheritance

class ProtectedDerived : protected Base {

void accessMembers() {

publicMember = 10; // public becomes protected

protectedMember = 20; // protected remains protected

// privateMember = 30; // Error: private not accessible

}

};

// Private inheritance

class PrivateDerived : private Base {

void accessMembers() {

publicMember = 10; // public becomes private

protectedMember = 20; // protected becomes private

// privateMember = 30; // Error: private not accessible

}

};

int main() {

PublicDerived pd;

pd.publicMember = 100; // OK: public member accessible

ProtectedDerived ptd;

// ptd.publicMember = 100; // Error: now protected, not accessible outside

PrivateDerived pvd;

// pvd.publicMember = 100; // Error: now private, not accessible outside

}Advanced Encapsulation Patterns

The Pimpl (Pointer to Implementation) Idiom

The Pimpl idiom is an advanced encapsulation technique that completely hides implementation details from the header file:

// Widget.h

class Widget {

private:

class Impl; // Forward declaration

Impl* pImpl; // Pointer to implementation

public:

Widget();

~Widget();

void doSomething();

void doSomethingElse(int value);

// Prevent copying (or implement carefully)

Widget(const Widget&) = delete;

Widget& operator=(const Widget&) = delete;

};

// Widget.cpp

#include "Widget.h"

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

// Implementation class defined only in .cpp file

class Widget::Impl {

public:

std::vector<int> data;

std::string name;

int counter;

void process() {

std::cout << "Processing " << name << std::endl;

counter++;

}

};

Widget::Widget() : pImpl(new Impl()) {

pImpl->name = "Widget";

pImpl->counter = 0;

}

Widget::~Widget() {

delete pImpl;

}

void Widget::doSomething() {

pImpl->process();

}

void Widget::doSomethingElse(int value) {

pImpl->data.push_back(value);

std::cout << "Added value: " << value << std::endl;

}The Pimpl idiom offers several benefits:

- Reduces compilation dependencies (changes to Impl don’t require recompiling clients)

- Completely hides implementation details

- Maintains binary compatibility across library versions

Interface Classes (Abstract Base Classes)

Creating pure interfaces with abstract base classes is another powerful encapsulation pattern:

// Pure interface - no implementation details exposed

class IDataStore {

public:

virtual ~IDataStore() = default;

virtual bool save(const string& key, const string& value) = 0;

virtual string load(const string& key) = 0;

virtual bool remove(const string& key) = 0;

virtual bool exists(const string& key) = 0;

};

// Concrete implementation - file-based storage

class FileDataStore : public IDataStore {

private:

string directory;

map<string, string> cache;

string getFilePath(const string& key) {

return directory + "/" + key + ".dat";

}

public:

FileDataStore(const string& dir) : directory(dir) {}

bool save(const string& key, const string& value) override {

cout << "Saving to file: " << getFilePath(key) << endl;

cache[key] = value;

// In real implementation, write to file

return true;

}

string load(const string& key) override {

if (cache.find(key) != cache.end()) {

return cache[key];

}

cout << "Loading from file: " << getFilePath(key) << endl;

// In real implementation, read from file

return "";

}

bool remove(const string& key) override {

cache.erase(key);

cout << "Removing file: " << getFilePath(key) << endl;

return true;

}

bool exists(const string& key) override {

return cache.find(key) != cache.end();

}

};

// Alternative implementation - memory-based storage

class MemoryDataStore : public IDataStore {

private:

map<string, string> data;

public:

bool save(const string& key, const string& value) override {

cout << "Saving to memory" << endl;

data[key] = value;

return true;

}

string load(const string& key) override {

auto it = data.find(key);

return (it != data.end()) ? it->second : "";

}

bool remove(const string& key) override {

return data.erase(key) > 0;

}

bool exists(const string& key) override {

return data.find(key) != data.end();

}

};

// Client code works with interface, doesn't know implementation

class UserManager {

private:

IDataStore* dataStore;

public:

UserManager(IDataStore* store) : dataStore(store) {}

void registerUser(const string& username, const string& email) {

dataStore->save(username, email);

cout << "User registered: " << username << endl;

}

string getUserEmail(const string& username) {

return dataStore->load(username);

}

};Common Encapsulation Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake 1: Making Everything Public

// Bad: No encapsulation

class BadStudent {

public:

string name;

int age;

double gpa;

};

// Anyone can do this:

BadStudent student;

student.gpa = 5.0; // Invalid! GPA should be 0.0-4.0

student.age = -10; // Nonsense!Solution: Make data private and provide validated setters:

class GoodStudent {

private:

string name;

int age;

double gpa;

public:

void setGPA(double g) {

if (g >= 0.0 && g <= 4.0) {

gpa = g;

} else {

throw invalid_argument("GPA must be between 0.0 and 4.0");

}

}

};Mistake 2: Returning Non-Const References to Private Data

// Bad: Breaks encapsulation

class BadContainer {

private:

vector<int> data;

public:

vector<int>& getData() { // Returns modifiable reference!

return data;

}

};

// Caller can bypass all protection:

BadContainer container;

container.getData().clear(); // Oops! Direct modificationSolution: Return const references or copies:

class GoodContainer {

private:

vector<int> data;

public:

const vector<int>& getData() const { // Const reference

return data;

}

vector<int> getDataCopy() const { // Or return a copy

return data;

}

void addItem(int item) { // Controlled modification

data.push_back(item);

}

};Mistake 3: Using Public Member Variables “For Convenience”

// Bad: Convenient but dangerous

struct BadConfig {

string serverAddress; // Public - no validation

int port; // Public - could be set to invalid value

int maxConnections; // Public - could break system

};Solution: Even for simple data structures, use proper encapsulation:

class GoodConfig {

private:

string serverAddress;

int port;

int maxConnections;

public:

GoodConfig() : port(8080), maxConnections(100) {}

void setServerAddress(const string& addr) {

if (!addr.empty()) {

serverAddress = addr;

}

}

void setPort(int p) {

if (p > 0 && p < 65536) {

port = p;

} else {

throw invalid_argument("Port must be 1-65535");

}

}

void setMaxConnections(int max) {

if (max > 0 && max <= 10000) {

maxConnections = max;

} else {

throw invalid_argument("Max connections must be 1-10000");

}

}

string getServerAddress() const { return serverAddress; }

int getPort() const { return port; }

int getMaxConnections() const { return maxConnections; }

};Real-World Application: Building a Complete System

Let’s build a complete library management system demonstrating proper encapsulation:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <map>

#include <ctime>

using namespace std;

// Book class - encapsulates book data

class Book {

private:

string isbn;

string title;

string author;

int publicationYear;

bool isAvailable;

public:

Book(string isbn, string title, string author, int year)

: isbn(isbn), title(title), author(author),

publicationYear(year), isAvailable(true) {

if (isbn.empty() || title.empty()) {

throw invalid_argument("ISBN and title cannot be empty");

}

}

// Getters

string getISBN() const { return isbn; }

string getTitle() const { return title; }

string getAuthor() const { return author; }

int getPublicationYear() const { return publicationYear; }

bool checkAvailability() const { return isAvailable; }

// Controlled state changes

void checkOut() {

if (!isAvailable) {

throw runtime_error("Book is already checked out");

}

isAvailable = false;

}

void checkIn() {

isAvailable = true;

}

void displayInfo() const {

cout << "Title: " << title << endl;

cout << "Author: " << author << endl;

cout << "ISBN: " << isbn << endl;

cout << "Year: " << publicationYear << endl;

cout << "Status: " << (isAvailable ? "Available" : "Checked Out") << endl;

}

};

// Member class - encapsulates library member data

class LibraryMember {

private:

string memberId;

string name;

string email;

vector<string> checkedOutBooks; // Store ISBNs

int maxBooksAllowed;

public:

LibraryMember(string id, string name, string email, int maxBooks = 5)

: memberId(id), name(name), email(email), maxBooksAllowed(maxBooks) {

if (id.empty() || name.empty()) {

throw invalid_argument("Member ID and name cannot be empty");

}

}

string getMemberId() const { return memberId; }

string getName() const { return name; }

int getBooksCheckedOut() const { return checkedOutBooks.size(); }

bool canCheckOutMore() const {

return checkedOutBooks.size() < maxBooksAllowed;

}

void addCheckedOutBook(const string& isbn) {

if (!canCheckOutMore()) {

throw runtime_error("Maximum books limit reached");

}

checkedOutBooks.push_back(isbn);

}

void removeCheckedOutBook(const string& isbn) {

for (auto it = checkedOutBooks.begin(); it != checkedOutBooks.end(); ++it) {

if (*it == isbn) {

checkedOutBooks.erase(it);

return;

}

}

}

void displayInfo() const {

cout << "Member: " << name << " (ID: " << memberId << ")" << endl;

cout << "Email: " << email << endl;

cout << "Books Checked Out: " << checkedOutBooks.size()

<< "/" << maxBooksAllowed << endl;

}

};

// Library class - manages books and members

class Library {

private:

string libraryName;

map<string, Book*> books; // ISBN -> Book

map<string, LibraryMember*> members; // MemberID -> Member

// Private helper methods

bool bookExists(const string& isbn) const {

return books.find(isbn) != books.end();

}

bool memberExists(const string& memberId) const {

return members.find(memberId) != members.end();

}

public:

Library(string name) : libraryName(name) {}

~Library() {

// Clean up dynamically allocated objects

for (auto& pair : books) {

delete pair.second;

}

for (auto& pair : members) {

delete pair.second;

}

}

// Public interface for library operations

void addBook(const string& isbn, const string& title,

const string& author, int year) {

if (bookExists(isbn)) {

cout << "Book with this ISBN already exists!" << endl;

return;

}

books[isbn] = new Book(isbn, title, author, year);

cout << "Book added successfully: " << title << endl;

}

void registerMember(const string& memberId, const string& name,

const string& email) {

if (memberExists(memberId)) {

cout << "Member with this ID already exists!" << endl;

return;

}

members[memberId] = new LibraryMember(memberId, name, email);

cout << "Member registered successfully: " << name << endl;

}

bool checkOutBook(const string& memberId, const string& isbn) {

if (!memberExists(memberId)) {

cout << "Member not found!" << endl;

return false;

}

if (!bookExists(isbn)) {

cout << "Book not found!" << endl;

return false;

}

LibraryMember* member = members[memberId];

Book* book = books[isbn];

if (!member->canCheckOutMore()) {

cout << "Member has reached maximum books limit!" << endl;

return false;

}

if (!book->checkAvailability()) {

cout << "Book is not available!" << endl;

return false;

}

try {

book->checkOut();

member->addCheckedOutBook(isbn);

cout << "Book checked out successfully!" << endl;

return true;

} catch (const exception& e) {

cout << "Error: " << e.what() << endl;

return false;

}

}

bool returnBook(const string& memberId, const string& isbn) {

if (!memberExists(memberId) || !bookExists(isbn)) {

cout << "Member or book not found!" << endl;

return false;

}

Book* book = books[isbn];

LibraryMember* member = members[memberId];

book->checkIn();

member->removeCheckedOutBook(isbn);

cout << "Book returned successfully!" << endl;

return true;

}

void displayBookInfo(const string& isbn) const {

if (!bookExists(isbn)) {

cout << "Book not found!" << endl;

return;

}

books.at(isbn)->displayInfo();

}

void displayMemberInfo(const string& memberId) const {

if (!memberExists(memberId)) {

cout << "Member not found!" << endl;

return;

}

members.at(memberId)->displayInfo();

}

void displayAllAvailableBooks() const {

cout << "\n=== Available Books ===" << endl;

bool found = false;

for (const auto& pair : books) {

if (pair.second->checkAvailability()) {

pair.second->displayInfo();

cout << "---" << endl;

found = true;

}

}

if (!found) {

cout << "No available books." << endl;

}

}

};

// Main function demonstrating the system

int main() {

Library cityLibrary("City Central Library");

// Adding books

cityLibrary.addBook("978-0134685991", "Effective C++", "Scott Meyers", 2005);

cityLibrary.addBook("978-0201633610", "Design Patterns", "Gang of Four", 1994);

cityLibrary.addBook("978-0132350884", "Clean Code", "Robert Martin", 2008);

cout << "\n";

// Registering members

cityLibrary.registerMember("M001", "Alice Johnson", "alice@email.com");

cityLibrary.registerMember("M002", "Bob Smith", "bob@email.com");

cout << "\n";

// Display available books

cityLibrary.displayAllAvailableBooks();

cout << "\n";

// Check out books

cityLibrary.checkOutBook("M001", "978-0134685991");

cityLibrary.checkOutBook("M001", "978-0201633610");

cout << "\n";

// Try to check out unavailable book

cityLibrary.checkOutBook("M002", "978-0134685991");

cout << "\n";

// Display member info

cityLibrary.displayMemberInfo("M001");

cout << "\n";

// Return a book

cityLibrary.returnBook("M001", "978-0134685991");

cout << "\n";

// Now another member can check it out

cityLibrary.checkOutBook("M002", "978-0134685991");

return 0;

}This comprehensive library system demonstrates:

- Complete data hiding: All class data is private

- Controlled access: Only validated operations are allowed

- State management: Books can’t be checked out twice, members have borrowing limits

- Error handling: Invalid operations are caught and reported

- Clean interfaces: Public methods provide all necessary functionality

- Encapsulation hierarchy: Library manages Books and Members, each with their own encapsulation

Best Practices and Design Guidelines

1. Start with Private by Default

Make everything private unless there’s a specific reason to expose it. It’s easier to expand access later than to restrict it without breaking existing code.

2. Use Getters Judiciously

Not every private member needs a getter. Only provide getters for data that external code legitimately needs to access.

3. Validate in Setters

Every setter should validate input to maintain object invariants. Never assume callers will provide valid data.

4. Prefer Immutability When Possible

For data that shouldn’t change after construction, make it const and initialize it in the constructor:

class Person {

private:

const string birthDate; // Can't change after construction

string currentAddress; // Can be updated

public:

Person(string birth, string address)

: birthDate(birth), currentAddress(address) {}

string getBirthDate() const { return birthDate; }

void updateAddress(const string& newAddress) {

currentAddress = newAddress;

}

};5. Design for Extension

When creating base classes, use protected for members that derived classes might need, but keep truly private implementation details as private.

6. Document Access Decisions

When you make something public or protected, document why. This helps future maintainers understand your design decisions.

class DataProcessor {

protected:

// Protected to allow derived classes to implement

// custom validation logic

virtual bool validateData(const string& data) {

return !data.empty();

}

private:

// Private because the processing algorithm is

// an implementation detail that shouldn't be overridden

void processInternal(const string& data) {

// Complex processing logic

}

public:

bool process(const string& data) {

if (validateData(data)) {

processInternal(data);

return true;

}

return false;

}

};Conclusion: Building Better Software Through Encapsulation

Encapsulation is far more than just making data private—it’s a fundamental design philosophy that shapes how you structure your entire codebase. By hiding implementation details, validating state changes, and providing clean interfaces, you create software that is more maintainable, more secure, and more flexible.

The three access specifiers in C++—private, public, and protected—give you precise control over how your classes expose functionality. Private members protect your data and hide implementation details. Public members define your class’s interface and contract with the outside world. Protected members enable inheritance while maintaining encapsulation from external code.

Throughout this guide, you’ve seen how encapsulation prevents invalid states, enables implementation changes without breaking client code, simplifies complex systems, and creates clear boundaries between different parts of your program. From basic getters and setters to advanced patterns like Pimpl and interface-based design, encapsulation tools give you the power to build robust, professional-quality software.

As you continue your C++ journey, make encapsulation a habit. Always ask yourself: “Does this need to be public? Could someone misuse direct access to this data? How can I make my interface minimal but complete?” These questions will guide you toward better designs that stand the test of time.

Remember that good encapsulation is about finding the right balance. Too much encapsulation can make your code overly complex and difficult to use. Too little leaves your code vulnerable to bugs and hard to maintain. The key is understanding your class’s purpose, who will use it, and what guarantees you need to maintain about its state.

Master encapsulation, and you’ll write C++ code that is not just functional, but elegant, maintainable, and robust—code that you and your team will be proud to work with for years to come.