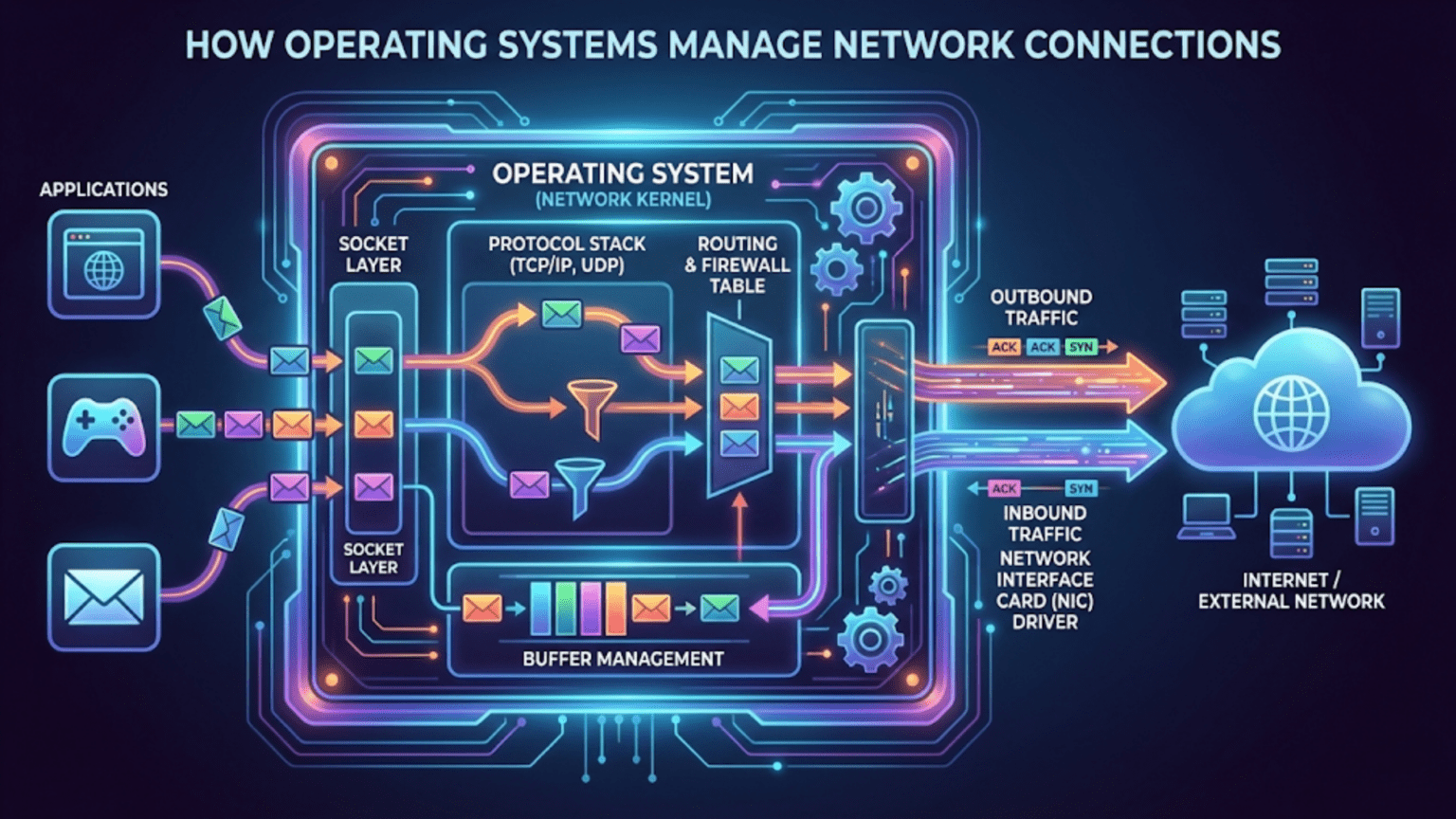

Operating systems manage network connections by implementing networking protocols, controlling network interface cards (NICs), handling data packet transmission and reception, and maintaining routing tables. The OS networking stack processes requests from applications, translates them into network-compatible formats, and manages the entire communication lifecycle from connection establishment to termination while ensuring data security and reliability.

In today’s interconnected world, your ability to browse websites, stream videos, send emails, or participate in video calls depends entirely on how effectively your operating system manages network connections. Every time you connect to the internet or communicate with another device on your local network, your operating system performs an incredibly complex series of tasks behind the scenes. Understanding how operating systems handle these network connections reveals one of the most sophisticated aspects of modern computing and helps you appreciate the engineering marvel that enables our connected digital lives.

Network connection management represents one of the most critical responsibilities of modern operating systems. Whether you’re using Windows, macOS, Linux, Android, or iOS, the operating system serves as the intermediary between your applications and the physical network hardware, translating high-level requests like “load this webpage” into the low-level network communications that make it happen. This comprehensive guide explores the intricate mechanisms, protocols, layers, and processes that operating systems use to establish, maintain, and terminate network connections, giving you a complete understanding of how your computer communicates with the world.

The Fundamental Architecture of OS Network Management

Operating systems approach network management through a structured, layered architecture that divides networking responsibilities into distinct functional layers. This architectural approach, commonly known as the networking stack or network protocol stack, provides organization and modularity that makes network management both efficient and maintainable.

The most widely recognized networking model is the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model, which defines seven distinct layers of network functionality. However, most modern operating systems actually implement the TCP/IP model, which consolidates these functions into four practical layers: the Network Interface Layer (equivalent to OSI’s Physical and Data Link layers), the Internet Layer (equivalent to OSI’s Network layer), the Transport Layer (matching OSI’s Transport layer), and the Application Layer (combining OSI’s Session, Presentation, and Application layers).

Your operating system’s networking stack begins at the lowest level with the Network Interface Layer, where it directly interacts with your network hardware. At this foundational level, the OS contains device drivers that communicate with your Network Interface Card (NIC), whether that’s an Ethernet adapter, Wi-Fi radio, or mobile cellular modem. These drivers translate the OS’s high-level commands into specific instructions that the network hardware can execute, handling tasks like activating the radio, setting transmission power, and managing the physical connection state.

Moving up the stack, the Internet Layer handles addressing and routing of data packets. This is where your operating system implements the Internet Protocol (IP), managing IP addresses, creating and interpreting packet headers, and determining the best path for data to reach its destination. When your computer needs to send data to another device, the OS at this layer ensures each packet contains the correct source and destination IP addresses and handles fragmentation when data is too large to send in a single packet.

The Transport Layer provides end-to-end communication services for applications. Here, the operating system implements protocols like TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and UDP (User Datagram Protocol). TCP provides reliable, ordered delivery of data streams, while UDP offers faster but less reliable connectionless communication. Your OS manages ports at this layer, allowing multiple applications to use the network simultaneously by giving each connection a unique port number identifier.

Finally, the Application Layer represents where your applications interact with the networking stack. When you open a web browser or email client, these applications use operating system APIs to initiate network connections. The OS provides socket interfaces that applications use to send and receive data, abstracting away all the complexity of the lower layers and presenting programmers with relatively simple function calls like “connect,” “send,” and “receive.”

Network Interface Discovery and Configuration

Before your operating system can manage network connections, it must first discover and configure the available network interfaces on your system. This process begins immediately during the boot sequence and continues dynamically as you connect or disconnect network devices.

When your computer starts, the operating system’s hardware detection mechanisms scan for available network adapters. On modern systems, this happens through hardware enumeration processes that query the computer’s buses (PCI, PCIe, USB) to identify connected devices. When the OS detects a network interface card, it loads the appropriate device driver from its driver database. These drivers contain the specific instructions needed to communicate with particular network hardware models, translating generic OS commands into vendor-specific device operations.

Once the driver is loaded, the operating system creates a network interface object in its internal data structures. This interface object serves as the OS’s representation of the physical hardware, maintaining information about the device’s capabilities, current state, and configuration. You can typically see these interfaces through your operating system’s network management tools—on Windows, the Network Connections panel shows each adapter; on Linux, commands like ip link or ifconfig display available interfaces; and on macOS, the Network preference pane lists all detected adapters.

The next critical step is address configuration. For your device to communicate on a network, it needs unique identifiers at multiple layers. At the hardware level, every network interface has a MAC (Media Access Control) address, a unique 48-bit identifier burned into the hardware at manufacturing time. Your operating system reads this MAC address from the device and uses it for local network communication.

At the network level, your device needs an IP address to participate in internet communications. Operating systems support several methods for obtaining IP addresses. The most common approach in modern networks is DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol). When you connect to a network, your operating system’s DHCP client component sends a broadcast message requesting network configuration. A DHCP server on the network responds with an IP address, subnet mask, default gateway, and DNS server addresses. Your OS automatically configures the network interface with these parameters, making the connection process seamless and automatic.

Alternatively, operating systems support static IP configuration, where you manually specify all network parameters. This approach is common in server environments where consistent addressing is important. The OS stores these static configurations and applies them to the interface whenever it becomes active. Some operating systems also support automatic private IP addressing (APIPA), where if DHCP fails, the OS automatically assigns itself an address from a reserved private range (169.254.0.0/16), allowing at least local network communication.

Modern operating systems maintain sophisticated network profiles that remember configurations for different networks. When you connect to a previously visited Wi-Fi network, your OS recalls the security credentials, IP configuration preferences, and other settings associated with that network. This profile system makes reconnection automatic and seamless while allowing different configurations for home, work, and public networks.

The Network Connection Establishment Process

When an application on your computer wants to establish a network connection, it triggers a complex sequence of operations within your operating system. Understanding this process reveals how the OS transforms a simple request like “connect to this server” into actual network communication.

The process typically begins when an application makes a socket system call. Sockets represent endpoints of network communication, and creating a socket tells the operating system that the application wants to perform network operations. When your web browser wants to fetch a webpage, it creates a socket and specifies the type of communication (TCP for reliable web traffic, for instance).

For TCP connections, the operating system then initiates the famous three-way handshake process. First, the OS constructs a TCP packet with the SYN (synchronize) flag set and sends it to the destination server. This SYN packet includes an initial sequence number that will be used to track data order throughout the connection. The packet also travels down through the networking stack—the Transport Layer adds TCP headers including source and destination ports, the Internet Layer adds IP headers with addressing information, and the Network Interface Layer adds frame headers before transmitting the physical signals.

When the destination server’s operating system receives this SYN packet, its networking stack processes the packet upward through its layers. If the server is willing to accept the connection (the application is listening on the specified port, firewall rules permit it, etc.), the server’s OS sends back a SYN-ACK packet, acknowledging the connection request and sending its own sequence number. Finally, the client operating system sends an ACK packet to complete the handshake, and the connection is established. This three-way handshake ensures both sides are ready to communicate and agree on initial parameters.

Throughout this process, your operating system maintains a connection state table, tracking each active connection with details like local and remote IP addresses, port numbers, connection state (SYN_SENT, ESTABLISHED, etc.), sequence numbers, and associated socket data structures. This table allows the OS to properly route incoming packets to the correct application and maintain multiple simultaneous connections.

For UDP communication, the process is simpler since UDP is connectionless. The application creates a UDP socket, and the OS can immediately send datagrams without establishing a formal connection. This makes UDP faster for applications that can tolerate some packet loss, like video streaming or online gaming.

Operating systems also implement connection pooling and management optimizations. When multiple connections go to the same destination, the OS might reuse certain connection parameters. Modern operating systems implement TCP Fast Open, which allows data to be sent during the initial SYN packet, reducing connection establishment latency for subsequent connections to known servers.

Data Transmission and Reception Management

Once a network connection is established, your operating system manages the continuous flow of data between your application and the remote endpoint. This ongoing management involves sophisticated buffering, scheduling, and protocol handling that ensures efficient and reliable data transfer.

When your application wants to send data, it typically calls a send or write function on its socket, passing a buffer containing the data to transmit. Your operating system doesn’t necessarily send this data immediately. Instead, it copies the data from the application’s user-space buffer into kernel-space send buffers. This buffering serves several important purposes: it decouples the application’s writing speed from the actual network transmission speed, allows the OS to batch small writes into larger network packets for efficiency, and enables the application to continue working while the OS handles the actual transmission in the background.

The operating system’s TCP implementation makes critical decisions about when and how to send buffered data. For efficiency, TCP uses algorithms like Nagle’s algorithm, which delays sending small packets to allow them to be combined into larger, more efficient transmissions. However, for interactive applications where latency matters more than efficiency (like SSH sessions or gaming), applications can disable Nagle’s algorithm through socket options, and the OS respects these preferences.

As data moves down through the networking stack, each layer adds its own headers. The Transport Layer adds TCP or UDP headers containing port numbers, sequence numbers (for TCP), and checksums. The Internet Layer adds IP headers with source and destination addresses, protocol identifiers, and fragmentation information if the data exceeds the network’s Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU). The Network Interface Layer adds frame headers with MAC addresses for the next hop in the packet’s journey.

Your operating system also implements flow control mechanisms that prevent overwhelming the receiver. TCP’s sliding window protocol allows the receiver to tell the sender how much buffer space it has available. The OS’s TCP implementation respects these windows, slowing down transmission when the receiver’s buffers are filling up. This flow control happens transparently—applications don’t need to worry about it because the OS handles it automatically.

On the receiving side, your operating system processes incoming network traffic through interrupt handlers and network processing threads. When a packet arrives at your network interface card, the NIC triggers a hardware interrupt, causing the CPU to temporarily suspend what it’s doing and execute the network driver’s interrupt handler. This handler quickly copies the packet data from the NIC’s buffers into system memory and schedules further processing.

The actual packet processing happens in a separate software interrupt context (called NET_RX softirq in Linux, for example). Here, the OS processes packets up through the networking stack, verifying checksums, checking IP addresses, examining port numbers, and matching packets to the appropriate socket and application. If packets arrive out of order (common in IP networks), the OS’s TCP implementation reorders them before delivering data to the application, maintaining the stream abstraction that TCP provides.

Your operating system maintains receive buffers for each socket, where incoming data waits until the application is ready to read it. When the application calls a receive or read function, the OS copies data from these kernel buffers into the application’s user-space buffer. If data arrives faster than the application can process it, the buffers fill up, and the OS’s flow control mechanisms signal the sender to slow down.

Routing and Gateway Management

Routing represents one of the most critical functions your operating system performs in network management. Every packet your computer sends must be directed toward its destination, and your OS makes constant routing decisions that determine the path packets take through the network.

At the heart of your operating system’s routing functionality lies the routing table, a database that maps destination networks to the appropriate outbound interface and next-hop gateway. When you examine your routing table using commands like route print on Windows or ip route on Linux, you see entries that tell the OS where to send packets destined for different networks.

The routing table contains several types of entries. Host routes specify paths to individual IP addresses and have the highest priority. Network routes specify paths to entire networks, allowing a single entry to cover thousands or millions of addresses. The default route, typically shown as 0.0.0.0/0, catches all packets that don’t match more specific routes and usually points to your default gateway (your router).

When your application sends data, and that data travels down through the networking stack, the Internet Layer performs route lookup. The OS compares the destination IP address against its routing table entries, using longest prefix matching to find the most specific route. If you’re sending data to a device on your local network, the route lookup identifies that the destination is directly reachable through your local network interface. For destinations on the internet, the lookup typically matches the default route, directing packets to your gateway router.

Operating systems implement sophisticated routing table management. The routing table is dynamically updated based on network changes. When you connect to a new network, your OS adds routes for that network. If an interface goes down, the OS removes or marks as invalid the routes associated with that interface. Some operating systems support routing protocols like RIP or OSPF, which allow automatic route discovery and adjustment based on network topology changes, though these are more common in specialized router operating systems than in desktop systems.

Your OS also maintains an ARP (Address Resolution Protocol) cache, which maps IP addresses to MAC addresses for devices on your local network. Before sending a packet to a local destination, the OS must know the destination’s MAC address for the data link layer. If the address isn’t in the ARP cache, the OS sends an ARP request broadcast asking “Who has this IP address?” and the target device responds with its MAC address. Your OS caches these mappings to avoid repeated ARP requests for frequently contacted local devices.

The routing process also involves MTU path discovery, where your operating system determines the maximum packet size that can traverse the path to a destination without fragmentation. IP packets have a “Don’t Fragment” flag, and when set, routers that can’t forward a packet because it’s too large send back an ICMP “Packet Too Big” message. Your OS processes these messages and adjusts the path MTU for that destination, ensuring efficient transmission without fragmentation overhead.

Modern operating systems also implement policy-based routing, where routing decisions consider more than just the destination address. The OS can route packets differently based on source address, port numbers, protocol type, or packet markings. This allows sophisticated traffic management scenarios like sending traffic from different applications through different gateways or routing based on quality-of-service requirements.

DNS Resolution and Name Services

While IP addresses are the actual identifiers that network protocols use, humans prefer working with names. Your operating system includes comprehensive DNS (Domain Name System) resolution capabilities that translate human-readable names like “www.example.com” into IP addresses that the networking stack can use.

When an application requests a connection to a named host, the OS’s resolver component takes over. The resolver is a library of functions built into the operating system that implements DNS lookup protocols. Before making any network queries, the resolver first checks local sources. On most systems, this begins with the hosts file (located at /etc/.hosts on Unix-like systems or C:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc\.hosts on Windows), which allows manual mapping of names to addresses. System administrators use this file for local overrides or testing purposes.

If the name isn’t found locally, the resolver constructs a DNS query and sends it to the configured DNS server. Your operating system maintains a list of DNS servers, typically obtained through DHCP when you connect to a network, though you can configure them manually. The OS sends DNS queries as UDP packets to port 53 of these servers, requesting the IP address associated with the requested name.

Operating systems implement DNS caching to improve performance and reduce network traffic. When the OS receives a DNS response, it stores the result in a local DNS cache along with a time-to-live (TTL) value specified by the authoritative DNS server. Subsequent lookups for the same name hit this cache, returning results instantly without network queries. You can examine your DNS cache using commands like ipconfig /displaydns on Windows or inspect /etc/nscd.conf on Linux systems running nscd (name service cache daemon).

The DNS resolution process can involve multiple queries. For a query like “www.example.com,” if your OS’s configured DNS server doesn’t know the answer, it performs recursive resolution on your behalf, querying root DNS servers, then top-level domain servers, then authoritative servers for the domain, until it finds the answer. Your operating system’s resolver typically performs stub resolution, relying on recursive DNS servers to do this work, but some OS configurations support full recursive resolution.

Modern operating systems support DNS extensions and alternative resolution methods. DNSSEC (DNS Security Extensions) allows your OS to cryptographically verify DNS responses, preventing spoofing attacks. Some systems implement Multicast DNS (mDNS), which allows local name resolution without a DNS server—when you access “computername.local” on your network, your OS broadcasts the query and the target device responds directly. This is how Apple’s Bonjour and Linux’s Avahi systems provide zero-configuration networking.

Your OS also implements a service lookup system that extends beyond simple DNS. On Linux, the Name Service Switch (NSS) provides a flexible framework where name resolution can query multiple sources in configurable order—checking local files, DNS, LDAP directories, or other services. Windows implements similar functionality through its network provider interface, allowing different name resolution mechanisms to coexist.

Operating systems also handle DNS in failover and load balancing scenarios. If the primary DNS server doesn’t respond within a timeout period, the OS automatically tries secondary servers. When DNS returns multiple IP addresses for a single name (common for load-balanced services), different operating systems employ different strategies—some always use the first address, while others rotate through the addresses or randomize selection.

Firewall and Security Management

Network security represents a critical aspect of how operating systems manage connections. Modern operating systems include built-in firewall systems that control which network traffic is allowed to enter or leave your computer, implementing a first line of defense against network-based attacks.

Your operating system’s firewall functions as a packet filter, examining each incoming and outgoing packet and comparing it against a set of rules to determine whether to allow or block it. These firewall rules can consider multiple packet attributes: source and destination IP addresses, source and destination port numbers, protocol types (TCP, UDP, ICMP), packet direction (inbound or outbound), and the network interface involved.

On Windows, the Windows Defender Firewall (formerly Windows Firewall) is integrated deeply into the networking stack. When a packet arrives, before it’s delivered to any application, the Windows Filtering Platform evaluates it against the configured firewall rules. Windows maintains separate rule sets for different network profile types (Domain, Private, and Public), automatically applying stricter rules when you connect to public networks. The OS detects network type based on factors like whether it can reach a domain controller or what you specify during first connection.

Linux systems typically use netfilter, a kernel framework that provides packet filtering, network address translation, and other packet mangling capabilities. The iptables (or its successor nftables) userspace tools configure netfilter rules. When a packet enters a Linux system, it passes through various netfilter chains (PREROUTING, INPUT, FORWARD, OUTPUT, POSTROUTING), and the OS applies rules at each stage to determine packet fate. Linux’s firewall is extraordinarily flexible, supporting complex rule sets that can match on almost any packet characteristic and perform actions beyond simple allow/block, including packet modification and traffic shaping.

macOS implements its firewall through pf (packet filter), originally from OpenBSD. macOS’s Application Firewall focuses on application-level control, allowing you to specify whether individual applications can accept incoming connections rather than managing low-level port and address rules. When an application tries to listen for connections, macOS prompts you to allow or deny it, and the OS creates corresponding pf rules behind the scenes.

Stateful inspection represents a crucial feature of modern OS firewalls. Rather than just examining individual packets in isolation, your operating system’s firewall tracks connection states. When you initiate an outbound connection, the firewall creates a state entry tracking that connection. Return traffic for that connection is automatically allowed because it matches an existing state, even if no explicit allow rule exists. This stateful approach is more secure than simple packet filtering because it prevents unsolicited inbound traffic while seamlessly allowing responses to your legitimate outbound connections.

Operating systems also implement port security mechanisms. When an application wants to listen for incoming connections on a port, it must bind to that port through the OS. The operating system enforces that only one application can bind to a particular port at a time (though some OS allow port reuse with specific socket options). On Unix-like systems, binding to ports below 1024 (privileged ports) requires root access, a security measure that prevents ordinary users from running fake system services.

Beyond firewalls, operating systems implement various network security features. Most OS support IPsec (Internet Protocol Security), which can encrypt and authenticate all IP traffic between two points. When configured, your OS encrypts packets before transmission and decrypts incoming packets, making this transparent to applications. Virtual Private Network (VPN) support is built into modern operating systems, allowing your OS to tunnel all network traffic through an encrypted connection to a VPN server, often changing your apparent location and protecting your traffic from local network snooping.

Operating systems also implement network isolation features. Your OS can assign network interfaces to different security zones or namespaces. Container technologies use this—when you run a Docker container, your OS creates a separate network namespace for it, giving the container its own networking stack isolated from the host and other containers. This isolation prevents containerized applications from seeing or interfering with other network traffic on your system.

Wireless Network Management

Managing wireless network connections adds significant complexity beyond wired networking, and your operating system includes sophisticated systems to handle the unique challenges of wireless communication.

Your operating system’s wireless management begins with wireless network discovery. Wi-Fi radios can operate in multiple modes, but for typical client devices, they use managed mode where they connect to access points. Your OS instructs the wireless driver to periodically scan for available networks. During scanning, the wireless card tunes through different channels, listening for beacon frames that access points broadcast. These beacons contain the network’s SSID (name), supported data rates, security requirements, and other parameters.

The OS collects these scan results and presents them to you through the network connection interface. Behind the scenes, your operating system maintains a database of known networks, storing SSIDs, security credentials, and connection preferences. Modern operating systems rank available networks, automatically connecting to the strongest known network. The ranking algorithm considers signal strength, network security type, historical connection success, and user preferences.

When you select a network or when the OS automatically connects to a known network, it initiates the association process. For open networks, this is straightforward—the OS sends an association request to the access point, which responds with an association response if it accepts the connection. For secured networks, additional authentication steps occur.

Your operating system implements various wireless security protocols. WPA2 and WPA3 are the modern standards, and your OS includes supplicant software that handles the authentication process. For personal networks with a pre-shared key (password), your OS implements the four-way handshake protocol, exchanging messages with the access point to derive encryption keys without transmitting the actual password. For enterprise networks using 802.1X authentication, your OS includes an extensible authentication protocol (EAP) framework that can authenticate using various methods (username/password, digital certificates, etc.) through a RADIUS server.

Throughout the wireless connection, your operating system continuously monitors signal quality and link status. The wireless driver reports statistics like received signal strength (RSSI), signal-to-noise ratio, packet error rates, and supported data rates. Your OS uses this information to make roaming decisions. When signal quality degrades below a threshold, the OS can trigger a new scan and potentially roam to a different access point (if you’re in a network with multiple APs broadcasting the same SSID). The OS manages this transition, attempting to maintain active connections during the roaming process.

Power management is particularly important for wireless interfaces on battery-powered devices. Your operating system implements power-saving features defined in the 802.11 standard. It can instruct the wireless card to enter sleep states between beacon intervals, wake up only to check for buffered traffic at the access point, and reduce transmission power when link quality permits. The OS balances power savings against performance and latency requirements based on your power profile settings and current system state.

Operating systems also manage the complexity of multiple wireless standards and capabilities. Your Wi-Fi adapter might support 802.11a/b/g/n/ac/ax (Wi-Fi 6), operating on 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands with various channel widths and spatial streams. The OS negotiates capabilities with the access point, enabling the best possible connection given what both sides support. It handles band steering, automatically preferring 5 GHz when available for its better performance and less congestion, falling back to 2.4 GHz for range or compatibility.

For Bluetooth and other wireless technologies, operating systems implement separate management stacks. Bluetooth has a completely different protocol stack with profiles for different types of connections (audio, file transfer, input devices, etc.). Your OS manages Bluetooth pairing, storing link keys for paired devices, and automatically reconnecting to known devices when they’re in range. Modern OSes coordinate between Wi-Fi and Bluetooth (which share the 2.4 GHz spectrum) using coexistence mechanisms that prevent interference between the two radios.

Network Connection Monitoring and Diagnostics

Operating systems provide extensive monitoring and diagnostic capabilities that help both users and applications understand network connection status and troubleshoot problems.

Your operating system continuously monitors network interface status, tracking whether each interface is up or down, what addresses are configured, current link speed, and traffic statistics. You can access this information through various OS tools—on Windows, the Network and Sharing Center and Task Manager show connection status; on Linux, /sys/class/net/ provides extensive interface statistics; macOS’s Network Utility and Activity Monitor reveal similar information.

Operating systems maintain detailed per-connection statistics. For each active network connection, the OS tracks packets sent and received, bytes transferred, retransmissions (for TCP), connection state, and timing information. These statistics help applications implement features like download progress bars and help users identify bandwidth-consuming connections. System administrators use these statistics to diagnose performance problems and identify suspicious network activity.

Your OS implements network performance metrics collection. It measures latency (round-trip time for packets), packet loss rates, bandwidth utilization, and jitter (variation in packet arrival times). For TCP connections, the OS tracks congestion window sizes, slow start thresholds, and retransmission timeouts. These metrics allow the OS to optimize its networking behavior—adjusting TCP parameters based on observed network conditions, selecting among multiple available routes based on performance, and making intelligent decisions about connection management.

Network diagnostic tools are built into operating systems or provided as standard utilities. The ping command, available on virtually all operating systems, sends ICMP echo requests to test basic connectivity and measure round-trip latency. Your OS’s networking stack implements ICMP handling to respond to these requests and generate them. The traceroute (or tracert on Windows) tool shows the path packets take to reach a destination, revealing each router hop along the way. This works by sending packets with incrementally increasing TTL (time-to-live) values and processing the ICMP “Time Exceeded” messages that routers return.

Operating systems provide packet capture capabilities that allow detailed inspection of network traffic. Built-in functionality like tcpdump on Unix-like systems or the Network Monitor on Windows can capture packets in real-time, storing them for analysis. These tools operate at the network driver level, making copies of packets before they’re processed by the upper layers of the networking stack, providing visibility into exactly what’s happening on the wire.

Connection state information is accessible through various OS interfaces. Commands like netstat (network statistics) on all major operating systems display active connections, listening ports, and routing information. Modern alternatives like ss (socket statistics) on Linux provide faster, more detailed views. These tools read from kernel data structures that maintain connection state, giving you insight into what applications are communicating with what remote systems.

Operating systems also implement network event logging. Your OS records significant network events—interface up/down transitions, DHCP lease acquisitions, IP address changes, wireless association events, VPN connection establishment, and firewall rule violations. These logs, accessible through Event Viewer on Windows or syslog/journald on Linux systems, provide a historical record useful for troubleshooting intermittent problems and security investigations.

Quality of Service and Traffic Management

Modern operating systems implement sophisticated quality of service (QoS) mechanisms that prioritize certain network traffic over others, ensuring critical applications get the bandwidth and low latency they need.

Your operating system’s QoS implementation begins with traffic classification. The OS can identify different types of network traffic based on various characteristics: the application generating the traffic, destination addresses and ports, protocol types, and packet markings. Some applications explicitly request QoS treatment through socket options, telling the OS that their traffic requires low latency or guaranteed bandwidth. The OS honors these requests based on configured policies.

Traffic shaping is a key QoS mechanism where your operating system controls the rate at which packets are transmitted. Rather than sending data as fast as possible, the OS can meter out packets at specific rates, ensuring bandwidth is distributed according to policy. Linux implements this through the tc (traffic control) subsystem, which provides multiple queuing disciplines (qdiscs) that implement different shaping algorithms. Windows includes packet scheduling components that can limit bandwidth for specific applications or connection types.

Priority queuing allows your operating system to handle higher-priority traffic first. Your network interface card typically has multiple transmission queues, and the OS places packets into different queues based on priority. When the network hardware is ready to transmit, it selects from the highest-priority non-empty queue first. This ensures that time-sensitive traffic like VoIP (Voice over IP) or video conferencing gets transmitted with minimal delay, even when bulk file transfers are competing for bandwidth.

Operating systems also implement congestion avoidance mechanisms beyond basic TCP congestion control. Techniques like Random Early Detection (RED) or Controlled Delay (CoDel) can be configured on Linux systems, where the OS starts dropping packets before queues completely fill, signaling to TCP endpoints to slow down before severe congestion occurs. This prevents bufferbloat, where large buffers fill with packets causing increased latency for all traffic.

Differentiated Services (DiffServ) is a QoS framework that operating systems support for marking packets. Your OS can set the DiffServ Code Point (DSCP) field in IP packet headers, marking packets with priority levels. Network routers that support DiffServ read these markings and treat packets accordingly. Your OS can mark packets based on application, user preferences, or policies, ensuring your traffic gets appropriate treatment across the network path.

For advanced scenarios, operating systems support bandwidth reservation protocols. RSVP (Resource Reservation Protocol) allows applications to request specific bandwidth guarantees through the OS, which then signals these requirements to network devices along the path. While RSVP isn’t widely deployed on the internet, it’s used in some enterprise and telecommunications environments where guaranteed service levels are required.

Operating systems also implement traffic policing, enforcing limits on network usage. Corporate IT departments can configure policies that limit bandwidth usage per application, per user, or per network. Your OS enforces these limits, dropping or delaying packets that exceed configured rates. Windows Group Policy and Linux cgroups (control groups) provide mechanisms for implementing and enforcing such policies.

Network Virtualization and Namespaces

Modern operating systems provide powerful network virtualization capabilities that allow multiple isolated network environments to coexist on a single physical machine.

Network namespaces, particularly prevalent in Linux but available in various forms on other systems, create completely isolated networking stacks within the operating system. Each namespace has its own set of network interfaces, routing tables, firewall rules, and socket associations. When you create a new network namespace, the OS duplicates all networking-related kernel data structures, giving that namespace a completely independent view of the network.

This virtualization enables container technologies. When you run a container, your operating system creates a new network namespace for it. From the container’s perspective, it has its own network interfaces and can bind to any ports without conflicting with other containers or the host. The container is unaware that it’s sharing a physical network interface with other containers and the host operating system.

Your OS implements virtual network interfaces that connect these isolated namespaces. Virtual Ethernet (veth) pairs create a virtual cable—traffic sent into one end emerges from the other. The OS can place each end in a different namespace, allowing namespaces to communicate. These virtual interfaces function just like physical interfaces from the networking stack’s perspective, but they’re entirely software constructs that your OS manages.

Network bridges are software constructs that your operating system uses to connect multiple network interfaces at layer 2, similar to a physical network switch. When you create a bridge, the OS forwards Ethernet frames between connected interfaces based on MAC addresses. Container networking typically uses bridges—the OS creates a bridge on the host, attaches virtual interfaces from multiple containers, and bridges them together, allowing inter-container communication.

Network Address Translation (NAT) is another virtualization technique operating systems use extensively. Your OS can translate private IP addresses used within namespaces or virtual machines to public addresses used on external networks. When a packet exits a namespace through NAT, the OS rewrites the source IP address (and often the source port) to the host’s address, maintaining a translation table. Return traffic is recognized and translated back to the original internal address. This allows multiple isolated environments to share a single external IP address.

Software-defined networking (SDN) capabilities in modern operating systems provide programmatic control over network behavior. Open vSwitch, commonly used on Linux, implements an OpenFlow-compatible virtual switch entirely in software. Your OS can create complex virtual network topologies with this switch, defining flows that determine how packets are forwarded, modified, or dropped based on extremely flexible matching criteria.

VLANs (Virtual Local Area Networks) support in operating systems allows a single physical interface to carry traffic for multiple virtual networks. Your OS can create VLAN interfaces that tag packets with VLAN IDs, allowing network segmentation. This is common in server environments where administrators want to isolate different types of traffic (management, storage, application) on the same physical network.

Operating systems also support overlay networks, where the OS encapsulates network traffic in packets that can traverse existing network infrastructure. Technologies like VXLAN (Virtual Extensible LAN) or Geneve allow your OS to create large-scale virtual networks that span multiple physical machines. The OS handles encapsulation transparently—applications in one virtual network communicate as if they’re on the same layer 2 segment, even when they’re actually on different physical networks or data centers, with the OS encapsulating their traffic in UDP packets that tunnel through the underlying infrastructure.

Mobile and Power-Aware Network Management

Operating systems on mobile devices face unique network management challenges, particularly around power consumption, and have developed specialized approaches to handle them.

Your mobile operating system implements sophisticated radio resource management. Cellular radios consume significant power, particularly when transmitting. The OS minimizes radio usage by batching network requests—instead of allowing apps to make network requests whenever they want, the OS can delay and group requests, activating the radio less frequently for longer periods rather than constantly waking it for brief transmissions. This batching can reduce power consumption by 30-50% while introducing minimal latency for non-urgent requests.

Mobile operating systems use connection coalescing, where the OS proxies connections on behalf of applications. Instead of each app maintaining its own connection to a server, the OS can multiplex multiple apps’ traffic over shared connections. This reduces the number of active connections the radio must maintain and allows better optimization of radio state transitions.

Fast dormancy is a technique mobile OSes use to transition cellular radios to low-power states quickly. After a data transmission completes, rather than leaving the radio in a high-power state waiting for more data, the OS signals the network that no more data is coming, allowing the radio to return to idle state faster. Your OS negotiates this capability with the cellular network during connection setup.

Mobile operating systems implement background data policies that restrict or shape network usage for applications not actively being used. iOS’s background app refresh and Android’s doze mode limit when background apps can access the network. When the screen is off and the device is stationary, your OS severely restricts background networking, allowing only high-priority notifications and critical system updates. This extends battery life significantly while maintaining responsiveness for important communications.

Wi-Fi offloading is a mobile OS strategy where the system prefers Wi-Fi connections over cellular when available. Your mobile OS continuously scans for known Wi-Fi networks, and when it finds one, it can seamlessly transition active connections from cellular to Wi-Fi. This transition happens at the IP layer—the OS maintains both interfaces active briefly during the transition, completing the migration before closing the cellular connection. This provides better performance and reduces cellular data usage without interrupting active applications.

Mobile operating systems also implement per-app network controls. You can configure whether individual apps can use cellular data, background data, or only Wi-Fi. Your OS enforces these restrictions by filtering network access attempts through these policies, blocking connections that violate configured rules. This gives you fine-grained control over your data usage and allows you to restrict untrusted apps’ network access.

Adaptive connectivity is a feature where mobile OSes adjust network behavior based on signal quality and network conditions. When your OS detects poor connectivity (high latency, frequent packet loss), it can adjust TCP parameters, reduce background synchronization frequency, and modify app behavior to work better on degraded networks. Some mobile OSes implement prefetching strategies, downloading content when connectivity is good so apps can function offline or on poor connections.

Network Protocol Optimization and Performance Tuning

Operating systems continuously evolve their network protocol implementations, incorporating optimizations that improve performance, reduce latency, and increase throughput.

TCP congestion control represents a critical area where operating systems implement sophisticated algorithms. Traditional TCP used algorithms like Reno and New Reno, but modern operating systems support multiple algorithms—CUBIC (default in Linux and Windows), BBR (Bottleneck Bandwidth and RTT, from Google), and others. Each algorithm takes a different approach to detecting available bandwidth and responding to congestion. Your OS allows changing the congestion control algorithm, enabling tuning for specific network conditions. High-latency networks might perform better with different algorithms than low-latency local networks.

Operating systems implement receive window scaling, which allows TCP windows larger than the original 65,535-byte limit. For high-bandwidth, high-latency networks (like satellite connections or cross-country internet links), the bandwidth-delay product requires large windows to achieve full throughput. Your OS negotiates window scaling during the TCP three-way handshake, allowing windows up to 1 gigabyte. This single optimization can increase throughput by orders of magnitude on appropriate networks.

Selective acknowledgment (SACK) is another TCP enhancement that operating systems support. Traditional TCP acknowledges data cumulatively—an ACK for byte 1000 implies all bytes before 1000 were received. When packets are lost in the middle of a stream, this forces retransmission of all subsequent data, even if it was received correctly. SACK allows your OS’s TCP implementation to acknowledge non-contiguous blocks of data, requesting retransmission of only the actual lost packets. This significantly improves performance on lossy networks.

TCP Fast Open (TFO) is an optimization that modern operating systems implement to reduce connection establishment latency. Traditional TCP requires a full round trip before any application data can be sent (the three-way handshake). TFO allows the client to send data in the initial SYN packet and for the server to respond with data in the SYN-ACK, eliminating one round-trip time. Your OS implements TFO using cryptographic cookies to prevent certain types of attacks, and applications can enable it through socket options.

Operating systems also implement zero-copy mechanisms that reduce CPU overhead for network operations. Traditionally, sending a file over the network required reading it from disk into a user-space buffer, then copying that buffer into kernel space for transmission—two expensive copy operations. Zero-copy techniques like sendfile (Linux) or TransmitFile (Windows) allow the OS to transfer data directly from the file system cache to the network interface, bypassing user space entirely. This can reduce CPU usage and increase throughput by eliminating unnecessary data copying.

Offloading features, where your operating system delegates certain networking tasks to the network interface card, significantly improve performance. TCP Segmentation Offload (TSO) allows the OS to pass large chunks of data to the network card, which handles splitting them into appropriate-sized TCP segments. This reduces CPU usage because the OS doesn’t have to construct individual packets. Checksum offloading delegates checksum calculation to the hardware. Receive-side scaling (RSS) distributes incoming network packets across multiple CPU cores for parallel processing, improving multi-core systems’ network throughput.

Operating systems implement receive packet steering and RPS (Receive Packet Steering), software mechanisms that distribute incoming network processing across CPU cores even when the network hardware doesn’t support RSS. Your OS hashes packet headers to assign packets to specific CPUs, ensuring packets from the same connection are processed by the same CPU (maintaining cache efficiency) while distributing different connections across cores.

Network Failure Detection and Recovery

Robust network connection management requires operating systems to detect failures quickly and recover gracefully, ensuring applications experience minimal disruption.

Your operating system implements multiple layers of failure detection. At the physical layer, network drivers monitor link status. Most network interfaces provide carrier detection that indicates whether a physical connection exists. When you unplug an Ethernet cable, the interface detects loss of carrier within milliseconds and reports this to the OS, which marks the interface as down and notifies applications of connection failures.

For wireless connections, failure detection is more nuanced since radio links can degrade gradually. Your OS monitors signal quality, packet error rates, and missed beacons. When these metrics exceed thresholds, the OS concludes the connection has failed. The OS then attempts recovery—first trying to reassociate with the same access point, then scanning for alternative access points, and finally notifying applications if recovery fails.

TCP includes built-in keep-alive mechanisms that operating systems implement. When enabled for a connection, your OS periodically sends keep-alive probes (empty packets) to the remote endpoint. If the remote side doesn’t respond to multiple consecutive probes, the OS concludes the connection has failed and terminates it, notifying the application. The keep-alive interval and retry count are configurable OS parameters, allowing tuning for different scenarios.

Operating systems also implement dead gateway detection. If your default gateway stops responding (router failure), the OS detects this through multiple mechanisms: failed ARP requests to the gateway, ICMP errors from routing failures, or TCP connection timeouts. Some OSes actively probe gateways using ICMP echo requests. When gateway failure is detected, the OS can switch to an alternate gateway if one is configured, providing automatic failover.

Path MTU discovery failure recovery is another aspect OS networking stacks handle. If Path MTU discovery fails (because intervening routers don’t send proper ICMP messages), connections can hang trying to send packets that are too large. Operating systems implement timeouts and fallbacks, reducing the assumed path MTU after failures and eventually falling back to a safe minimum size (typically 576 bytes) to ensure communication continues even in pathological network conditions.

Your operating system implements exponential backoff for connection retry attempts. When a connection attempt fails, the OS doesn’t immediately retry—this would waste resources and could overwhelm the network. Instead, it waits a short period before the first retry, then doubles the wait time for each subsequent failure, up to a maximum. This approach quickly recovers from transient failures while avoiding resource waste on persistent failures.

Operating systems provide connection state recovery for applications. When a network connection fails, sophisticated applications can attempt recovery. Your OS provides APIs that notify applications of connection failures and allow them to re-establish connections. Some OSes support TCP connection migration, where a connection can survive IP address changes (important for mobile devices switching between Wi-Fi and cellular), though this requires special handling and isn’t universally supported.

For critical services, operating systems support connection redundancy. Multiple network interfaces can provide failover—if the primary interface fails, the OS automatically routes traffic through a backup interface. Technologies like bonding (Linux) or NIC teaming (Windows) allow multiple interfaces to be combined, providing both increased bandwidth and redundancy. The OS monitors individual interface health and redistributes traffic when failures occur.

Future Evolution of OS Network Management

Operating system network management continues to evolve rapidly as new technologies emerge and networking demands increase.

Software-defined networking integration is becoming deeper in operating systems. Future OSes will likely provide more extensive programmable networking capabilities, allowing applications and administrators to define complex network policies and behaviors through high-level APIs. The boundary between the network and the operating system will blur as OSes implement more network functions traditionally handled by dedicated hardware.

Zero-trust networking models are influencing OS design. Rather than trusting any network connection, future operating systems will likely implement pervasive encryption and authentication for all network traffic by default. Every connection will be verified, encrypted, and authorized, with the OS mediating all network access based on application and user identity rather than just network location.

AI and machine learning integration into network management represents an emerging trend. Operating systems may incorporate learning algorithms that analyze network patterns, predict problems before they occur, optimize protocol parameters automatically based on observed conditions, and detect anomalous behavior that could indicate security issues or performance problems.

Edge computing will influence how operating systems manage network connections. As computation moves closer to data sources, OSes will need to intelligently route application requests to nearby edge servers rather than distant cloud data centers. OS networking stacks will likely include location and latency awareness, automatically discovering and utilizing edge resources.

The conclusion of our journey through operating system network management reveals an intricate, multi-layered system that transforms simple application requests into global communications. Your operating system serves as the sophisticated intermediary that makes modern connected computing possible, handling everything from the electrical signals on network wires to the high-level protocols that applications depend upon. Understanding these mechanisms not only demystifies how your computer connects to the world but also provides insight into one of computer science’s most elegant and complex accomplishments—a system that allows billions of devices worldwide to communicate reliably, securely, and efficiently through countless networks, all coordinated by the operating systems running on each endpoint.

Summary Table: Key OS Network Management Components

| Component | Primary Function | Key Technologies | Operating System Responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Stack | Layered protocol implementation | TCP/IP, UDP, ICMP | Process packets through protocol layers, maintain connection state |

| Interface Management | Hardware control and configuration | NIC drivers, DHCP client, IP configuration | Detect adapters, configure addresses, manage link status |

| Routing System | Determine packet paths | Routing tables, ARP cache, gateway selection | Lookup routes, maintain forwarding tables, handle local/remote decisions |

| DNS Resolver | Name-to-address translation | DNS protocol, local caching, hosts file | Query name servers, cache results, provide name resolution to applications |

| Firewall | Security and access control | Packet filtering, stateful inspection, NAT | Evaluate packets against rules, track connection states, block unauthorized traffic |

| Wireless Management | Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity | 802.11 protocols, WPA2/WPA3, scanning | Discover networks, authenticate, manage signal quality, handle roaming |

| QoS Engine | Traffic prioritization | Queuing, shaping, marking | Classify traffic, enforce bandwidth limits, prioritize time-sensitive data |

| Virtual Networking | Network isolation and abstraction | Namespaces, bridges, virtual interfaces | Create isolated environments, connect virtual networks, implement SDN |

| Protocol Optimization | Performance enhancement | TCP algorithms, offloading, zero-copy | Implement congestion control, utilize hardware acceleration, reduce overhead |

| Monitoring & Diagnostics | Status tracking and troubleshooting | Statistics collection, logging, packet capture | Maintain metrics, provide diagnostic tools, detect and report failures |