Introduction

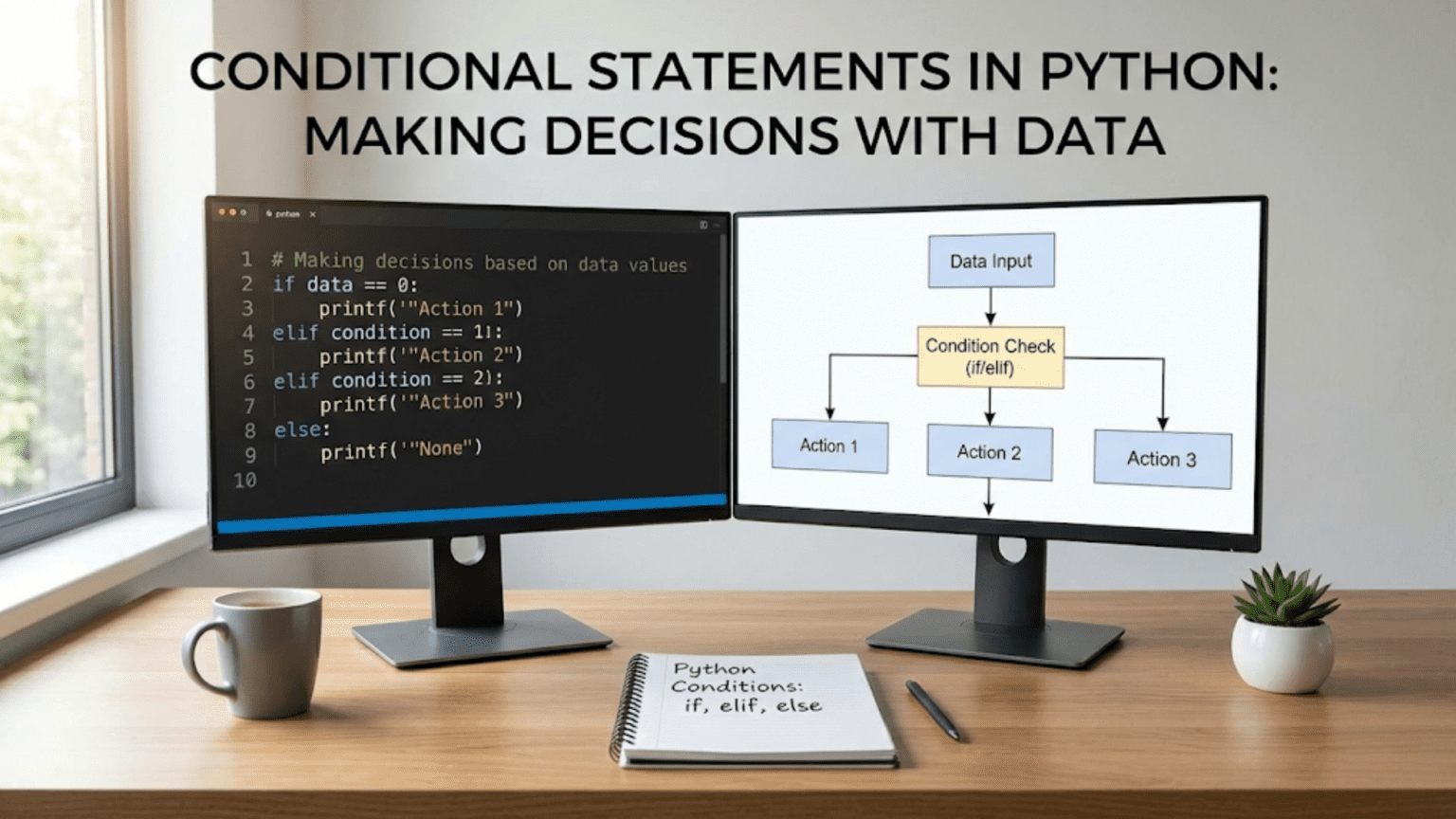

Every data analysis requires making decisions based on data. Should you include this observation in your analysis or exclude it as an outlier? How should you categorize this customer based on their purchase history? What transformation should you apply to this feature based on its current value? These questions all require conditional logic, the ability to execute different code depending on whether certain conditions are true or false. Without conditionals, your programs could only follow a single linear path regardless of the data they encounter, making them useless for real-world analysis where different situations demand different responses.

Conditional statements represent the decision-making mechanism in programming, letting your code adapt to different scenarios automatically. Just as you make decisions in everyday life based on conditions (if it is raining, take an umbrella; otherwise, do not), your Python programs make decisions based on data values. Temperature above freezing gets labeled differently than temperature below freezing. Sales above quota trigger bonuses while sales below trigger different actions. Test scores map to letter grades based on thresholds. All these decisions use conditional statements to choose which code executes.

For data scientists, conditional logic appears constantly in data cleaning, feature engineering, and analysis. You use conditionals to handle missing values differently than valid data, to apply transformations selectively based on feature characteristics, to filter datasets keeping only observations that meet criteria, and to categorize continuous variables into discrete bins. Machine learning algorithms themselves make countless conditional decisions during training and prediction. Understanding conditionals deeply enables you to write code that handles the messy reality of real data where different situations require different treatments.

This comprehensive guide takes you from your first if statement through confident mastery of conditional logic in Python. You will learn how if statements execute code only when conditions are true, how elif and else handle multiple alternative scenarios, how to combine multiple conditions with logical operators, and common patterns that appear repeatedly in data science code. You will also discover best practices for writing readable conditionals and avoiding common pitfalls. By the end, you will think naturally about when different code paths should execute based on data characteristics.

The Basic If Statement: Executing Code Conditionally

The simplest conditional statement uses the if keyword followed by a condition that evaluates to True or False, a colon, and indented code that runs only when the condition is true. If the condition is false, Python skips the indented code entirely:

temperature = 85

if temperature > 80:

print("It's hot outside!")This code checks whether temperature exceeds 80. Since 85 is greater than 80, the condition is true and the print statement executes. If temperature were 75, the condition would be false and nothing would print.

The condition can be any expression that evaluates to a boolean value. You have already seen comparison operators like greater than, but Python provides a full set:

age = 25

if age == 25:

print("Age is exactly 25")

if age != 30:

print("Age is not 30")

if age >= 18:

print("Adult")

if age < 65:

print("Not a senior")

if age <= 25:

print("25 or younger")Notice the double equals (==) for equality testing versus single equals (=) for assignment. This distinction causes common beginner errors:

# Wrong - assigns 30 to age instead of comparing

if age = 30: # SyntaxError

print("Age is 30")

# Correct - compares age to 30

if age == 30:

print("Age is 30")The indented block under an if statement can contain multiple lines:

score = 95

if score >= 90:

letter_grade = 'A'

bonus_points = 5

print(f"Excellent work! Grade: {letter_grade}")All three statements execute when the condition is true. Python uses indentation to determine which code belongs to the if block, so consistent indentation is crucial.

Conditions often involve variables comparing to constants, but they can include any valid expression:

# Comparing variables to variables

price = 50

budget = 100

if price < budget:

print("Within budget")

# Using calculations in conditions

quantity = 5

if quantity * price <= budget:

print("Can afford this quantity")

# Checking membership

available_sizes = ["Small", "Medium", "Large"]

requested_size = "Medium"

if requested_size in available_sizes:

print("Size available")The in operator checks whether a value exists in a collection, which proves extremely useful when filtering data:

valid_responses = ["yes", "no", "maybe"]

user_response = "yes"

if user_response in valid_responses:

print("Valid response received")Adding Else: Handling the Alternative Case

Often you want to execute one block of code when a condition is true and a different block when it is false. The else clause handles this second case:

temperature = 65

if temperature > 70:

print("Wear shorts")

else:

print("Wear long pants")When temperature exceeds 70, the first block executes. Otherwise, the second block executes. Exactly one of these blocks always runs, never both, never neither.

This pattern appears constantly in data processing:

# Categorizing values

income = 45000

if income > 50000:

tax_bracket = "high"

else:

tax_bracket = "low"

print(f"Tax bracket: {tax_bracket}")The else clause must immediately follow the if block with matching indentation. It does not need its own condition because it handles everything not covered by the if:

age = 16

if age >= 18:

status = "adult"

else:

status = "minor" # Handles all cases where age < 18You can use if-else to assign different values based on conditions:

# Handling edge cases

denominator = 0

if denominator != 0:

result = 100 / denominator

else:

result = None # or float('inf'), or raise an errorThis pattern prevents division by zero errors by checking the condition before attempting the operation.

For simple value assignment, Python provides a concise conditional expression:

# Standard if-else

if score >= 60:

status = "pass"

else:

status = "fail"

# Conditional expression (ternary operator)

status = "pass" if score >= 60 else "fail"This one-line form reads as “assign pass if condition is true, else assign fail.” Use it for simple cases where readability is not compromised, but prefer standard if-else for complex logic.

Using Elif: Handling Multiple Conditions

When you have more than two possible cases, elif (short for “else if”) lets you check multiple conditions in sequence:

score = 85

if score >= 90:

grade = 'A'

elif score >= 80:

grade = 'B'

elif score >= 70:

grade = 'C'

elif score >= 60:

grade = 'D'

else:

grade = 'F'

print(f"Grade: {grade}")Python checks each condition in order, executing the first block where the condition is true, then skipping all remaining conditions. For a score of 85, Python checks if it is at least 90 (false), then if it is at least 80 (true), assigns ‘B’, and skips the remaining conditions entirely.

This top-to-bottom evaluation order matters when conditions could overlap:

# Order matters!

value = 15

if value > 10:

category = "large"

elif value > 5:

category = "medium" # Never reaches here if value > 10

else:

category = "small"

# For value = 15, category = "large"

# The medium condition never gets checkedYou can have as many elif clauses as needed:

day_number = 3

if day_number == 1:

day_name = "Monday"

elif day_number == 2:

day_name = "Tuesday"

elif day_number == 3:

day_name = "Wednesday"

elif day_number == 4:

day_name = "Thursday"

elif day_number == 5:

day_name = "Friday"

elif day_number == 6:

day_name = "Saturday"

elif day_number == 7:

day_name = "Sunday"

else:

day_name = "Invalid"

print(day_name)Though for this specific pattern, a dictionary provides cleaner code:

days = {1: "Monday", 2: "Tuesday", 3: "Wednesday",

4: "Thursday", 5: "Friday", 6: "Saturday", 7: "Sunday"}

day_name = days.get(day_number, "Invalid")The else clause is optional. If you omit it, none of the blocks execute when all conditions are false:

temperature = 72

if temperature > 90:

print("Extremely hot")

elif temperature > 80:

print("Very hot")

elif temperature > 70:

print("Warm")

# No else - nothing prints if temperature <= 70However, including else often makes code more robust by handling unexpected cases:

user_input = "maybe"

if user_input == "yes":

response = True

elif user_input == "no":

response = False

else:

response = None # Handles unexpected input explicitlyCombining Conditions with Logical Operators

Often you need to check multiple conditions simultaneously. Logical operators and, or, and not let you combine conditions:

# Both conditions must be true

age = 25

income = 60000

if age >= 18 and income >= 50000:

print("Qualifies for premium account")The and operator returns True only when both conditions are true. If either is false, the entire expression is false.

The or operator returns True when at least one condition is true:

# At least one condition must be true

day = "Saturday"

if day == "Saturday" or day == "Sunday":

print("It's the weekend!")The not operator reverses a boolean value:

is_raining = False

if not is_raining:

print("No umbrella needed")You can combine multiple logical operators in complex conditions:

age = 25

has_license = True

has_insurance = True

if age >= 18 and has_license and has_insurance:

print("Approved to rent car")Parentheses clarify complex conditions and override default precedence:

# Without parentheses - ambiguous

if age >= 18 and has_license or has_insurance:

pass

# With parentheses - clear intent

if age >= 18 and (has_license or has_insurance):

passPython evaluates logical operators using short-circuit evaluation, stopping as soon as the outcome is determined:

# If age < 18, the second condition never evaluates

if age >= 18 and income >= 50000:

print("Qualifies")When age is less than 18, Python knows the entire and expression must be false without checking income, potentially avoiding errors if income is not defined.

Common pattern combining multiple related checks:

# Checking if value is within range

temperature = 72

if temperature >= 60 and temperature <= 80:

print("Comfortable temperature")

# Python allows chained comparisons

if 60 <= temperature <= 80:

print("Comfortable temperature")The chained comparison is more readable and Pythonic.

Nested Conditionals: Conditions Within Conditions

Sometimes you need to check additional conditions only after an initial condition is true. Nested if statements place one conditional inside another:

age = 25

has_license = True

if age >= 18:

if has_license:

print("Approved to drive")

else:

print("Need license first")

else:

print("Too young to drive")The inner if statement only executes when the outer condition is true. This creates a decision tree where each level narrows the possibilities.

Nesting can extend to multiple levels:

account_type = "premium"

account_balance = 5000

transaction_amount = 1000

if account_type == "premium":

if account_balance >= transaction_amount:

print("Transaction approved")

else:

if account_balance >= transaction_amount * 0.9:

print("Transaction approved with overdraft fee")

else:

print("Insufficient funds")

else:

if account_balance >= transaction_amount:

print("Transaction approved")

else:

print("Insufficient funds")However, deep nesting quickly becomes hard to read. Often you can flatten nested conditions using logical operators:

# Nested

if age >= 18:

if has_license:

print("Approved")

# Flattened with and

if age >= 18 and has_license:

print("Approved")Or by restructuring logic:

# Deeply nested

if condition1:

if condition2:

if condition3:

print("All conditions met")

# Flattened with early returns (in a function)

def check_conditions():

if not condition1:

return

if not condition2:

return

if not condition3:

return

print("All conditions met")Use nesting when additional conditions only make sense after outer conditions are met, but avoid excessive depth.

Common Conditional Patterns in Data Science

Several conditional patterns appear repeatedly in data science code. Recognizing these patterns helps you write effective data processing logic.

Filtering data based on conditions:

ages = [15, 22, 34, 17, 28, 19, 45]

adults = []

for age in ages:

if age >= 18:

adults.append(age)

print(adults) # [22, 34, 28, 19, 45]Handling missing or invalid data:

values = [10, None, 25, 0, 15, -5]

valid_values = []

for value in values:

if value is not None and value > 0:

valid_values.append(value)

print(valid_values) # [10, 25, 15]Categorizing continuous values into bins:

def categorize_age(age):

if age < 18:

return "minor"

elif age < 35:

return "young_adult"

elif age < 55:

return "middle_aged"

else:

return "senior"

ages = [15, 25, 45, 65]

categories = [categorize_age(age) for age in ages]

print(categories) # ['minor', 'young_adult', 'middle_aged', 'senior']Applying different transformations based on value characteristics:

def normalize_value(value, max_value):

if value > max_value:

return 1.0 # Cap at maximum

elif value < 0:

return 0.0 # Floor at minimum

else:

return value / max_value

values = [-5, 25, 50, 75, 150]

normalized = [normalize_value(v, 100) for v in values]

print(normalized) # [0.0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0]Validating data before processing:

def calculate_bmi(height_m, weight_kg):

if height_m <= 0 or weight_kg <= 0:

return None

bmi = weight_kg / (height_m ** 2)

if bmi < 18.5:

category = "underweight"

elif bmi < 25:

category = "normal"

elif bmi < 30:

category = "overweight"

else:

category = "obese"

return {"bmi": bmi, "category": category}

result = calculate_bmi(1.75, 70)

print(result) # {'bmi': 22.86, 'category': 'normal'}Handling edge cases in calculations:

def safe_divide(numerator, denominator):

if denominator == 0:

return None # or float('inf'), or raise ValueError

return numerator / denominator

result = safe_divide(10, 0)

print(result) # NoneCleaning text data with conditional transformations:

def clean_text(text):

if text is None:

return ""

# Convert to string if not already

if not isinstance(text, str):

text = str(text)

# Clean and standardize

cleaned = text.strip().lower()

return cleaned

texts = [" Hello ", None, 123, "WORLD"]

cleaned_texts = [clean_text(t) for t in texts]

print(cleaned_texts) # ['hello', '', '123', 'world']Best Practices for Writing Conditionals

Writing clear, maintainable conditional logic requires following established patterns and avoiding common pitfalls.

Keep conditions simple and readable:

# Complex - hard to understand

if not (value < 0 or value > 100) and isinstance(value, (int, float)):

pass

# Clearer - use intermediate variables

is_valid_range = 0 <= value <= 100

is_numeric = isinstance(value, (int, float))

if is_valid_range and is_numeric:

passUse positive conditions when possible:

# Negative - harder to read

if not is_invalid:

process_data()

# Positive - clearer

if is_valid:

process_data()Avoid redundant conditions:

# Redundant

if score >= 90:

if score <= 100: # Redundant if scores are always <= 100

grade = 'A'

# Better

if score >= 90:

grade = 'A'Use elif instead of multiple independent if statements when conditions are mutually exclusive:

# Inefficient - checks all conditions even after finding a match

if score >= 90:

grade = 'A'

if score >= 80 and score < 90:

grade = 'B'

if score >= 70 and score < 80:

grade = 'C'

# Better - stops at first match

if score >= 90:

grade = 'A'

elif score >= 80:

grade = 'B'

elif score >= 70:

grade = 'C'Handle all possible cases explicitly when appropriate:

# Missing cases - what if response is not yes or no?

if response == "yes":

proceed = True

elif response == "no":

proceed = False

# What about other values?

# Better - explicit handling of unexpected cases

if response == "yes":

proceed = True

elif response == "no":

proceed = False

else:

proceed = None # or raise ValueErrorAvoid deep nesting when possible:

# Deeply nested

def process_data(data):

if data is not None:

if len(data) > 0:

if validate_data(data):

return clean_data(data)

# Flattened with guard clauses

def process_data(data):

if data is None:

return None

if len(data) == 0:

return None

if not validate_data(data):

return None

return clean_data(data)Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Understanding frequent errors helps you write correct conditional logic.

Using assignment instead of comparison:

# Wrong - assigns rather than compares

if x = 5: # SyntaxError

print("x is 5")

# Correct

if x == 5:

print("x is 5")Comparing to True or False unnecessarily:

# Redundant

if is_valid == True:

print("Valid")

# Better

if is_valid:

print("Valid")Forgetting that 0, empty strings, and None are falsy:

value = 0

# This doesn't execute - 0 is falsy

if value:

print("Value exists")

# Be explicit about what you're checking

if value is not None:

print("Value exists")

# Or check type and truthiness

if isinstance(value, (int, float)):

print("Value is a number")Incorrect operator precedence without parentheses:

# Ambiguous - what executes when?

if x > 0 and y > 0 or z > 0:

pass

# Clear with parentheses

if (x > 0 and y > 0) or z > 0:

passForgetting the colon at the end of if, elif, or else:

# Syntax error - missing colon

if age >= 18

print("Adult")

# Correct

if age >= 18:

print("Adult")Inconsistent indentation:

# IndentationError - mixing tabs and spaces or wrong levels

if condition:

print("This") # Wrong indentation

print("That") # Correct indentationCombining Conditionals with Functions and Loops

Conditionals become even more powerful when combined with functions and loops, creating flexible data processing pipelines.

Filtering within loops:

numbers = [12, 7, 19, 4, 22, 15, 8]

# Count values meeting condition

count = 0

for num in numbers:

if num > 10:

count += 1

print(f"Numbers greater than 10: {count}")Using conditionals to modify loop behavior:

# Find first value meeting condition

numbers = [3, 7, 12, 5, 19, 8]

for num in numbers:

if num > 10:

print(f"Found: {num}")

break # Stop after finding first matchFunctions with conditional logic:

def categorize_and_process(value):

if value < 0:

return None # Invalid

elif value < 10:

return value * 2

elif value < 100:

return value * 1.5

else:

return value # No transformation for large values

results = [categorize_and_process(v) for v in [5, 15, 150]]

print(results) # [10, 22.5, 150]Conclusion

Conditional statements give your programs the ability to make decisions based on data, transforming simple linear scripts into intelligent code that adapts to different scenarios. The if statement executes code only when conditions are true. The elif and else clauses handle alternative scenarios systematically. Logical operators let you combine multiple conditions. Together, these tools enable you to write code that handles the complexity and variability of real-world data.

For data scientists, conditionals appear everywhere: filtering datasets to keep relevant observations, categorizing continuous variables into meaningful groups, handling missing or invalid data gracefully, applying different transformations based on feature characteristics, and validating inputs before processing. Every time you write code that behaves differently based on data values, you use conditional logic either explicitly or through higher-level abstractions built on these fundamentals.

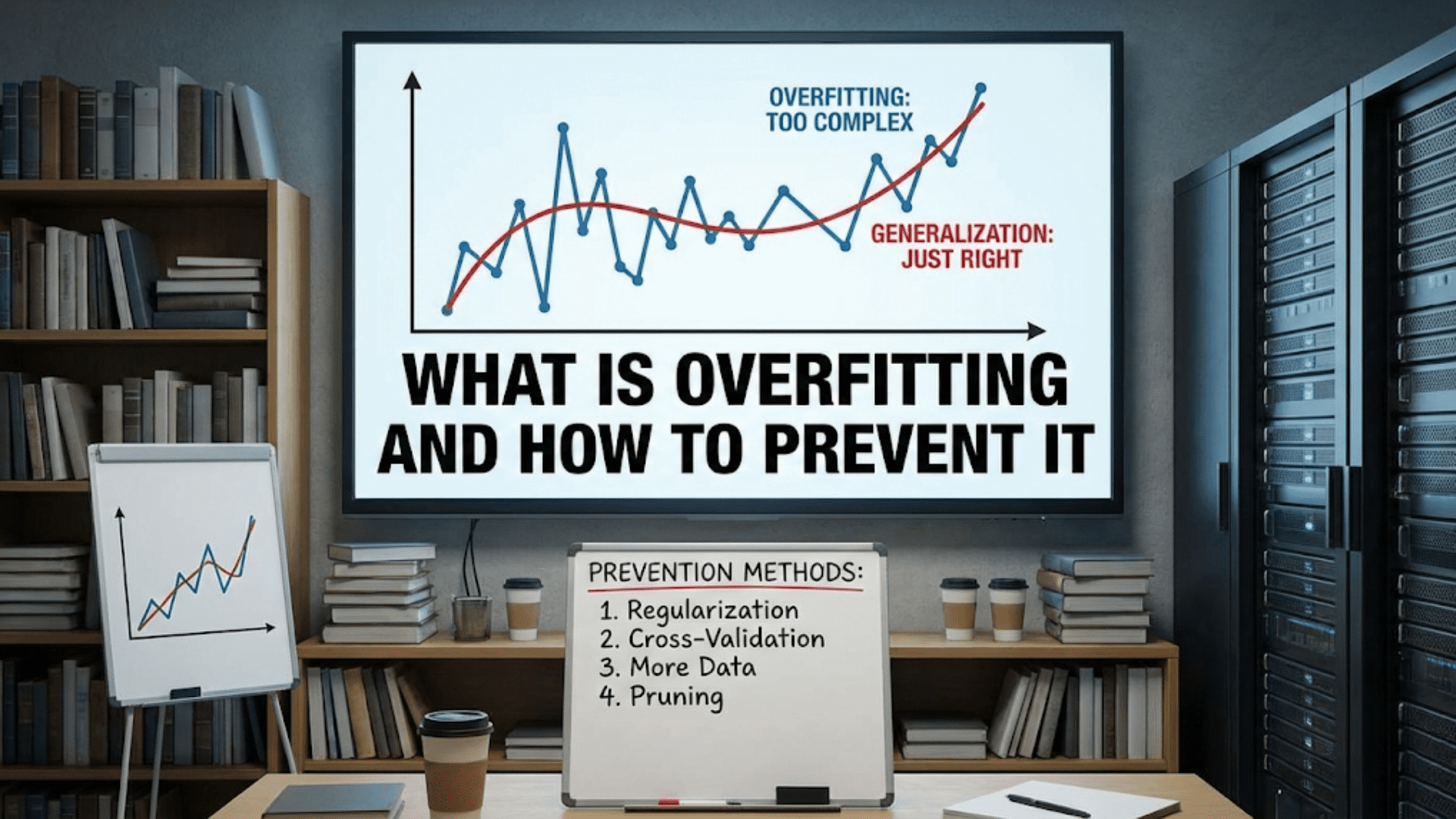

As you progress in data science, you will encounter more sophisticated decision-making patterns including vectorized conditionals in NumPy and pandas, decision trees in machine learning, and complex filtering pipelines. However, all these advanced techniques build directly on the conditional fundamentals you have learned here. The patterns of checking conditions, executing appropriate code paths, and handling edge cases transfer directly to these more advanced tools.

Practice writing conditionals for common scenarios: categorizing values, filtering data, handling special cases, and validating inputs. Build intuition about when to use if versus elif, when to combine conditions with logical operators, and when to flatten nested logic. The muscle memory you develop now makes conditional logic feel natural when you encounter it in real data science projects. Master conditionals, and you gain the power to write code that makes intelligent decisions about how to process data based on its characteristics and context.