Introduction

After mastering Python’s basic data types like integers, floats, strings, and booleans, you quickly encounter a fundamental limitation: these types only store single values. While you can create a variable for each piece of data you need, this approach becomes unmanageable when working with real datasets. Imagine trying to analyze survey responses from a thousand people by creating variables named person1_age, person2_age, person3_age, and so on. Clearly, you need better ways to organize and store collections of related information.

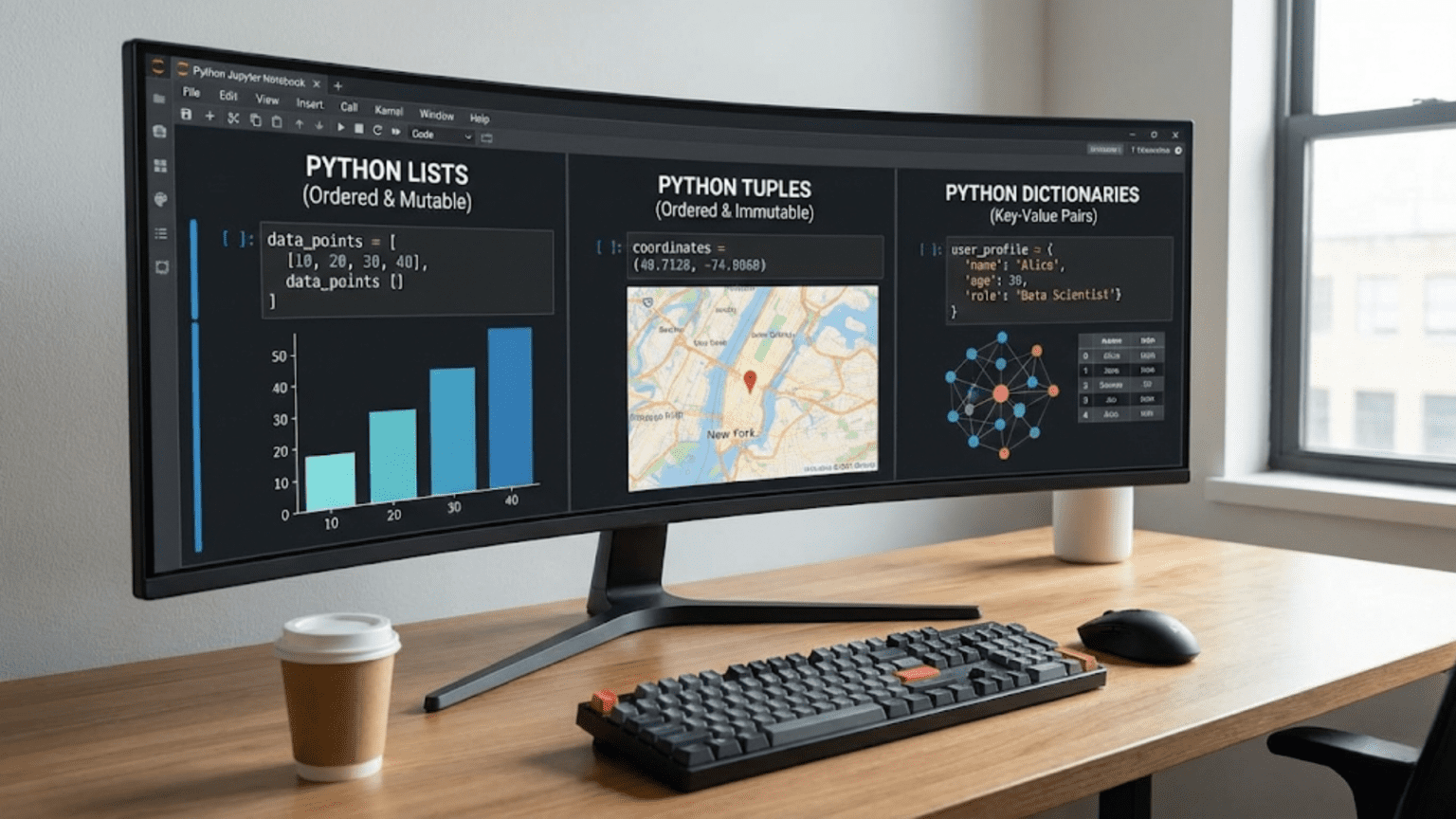

Python provides three fundamental data structures that solve this problem: lists, tuples, and dictionaries. These structures let you store multiple values together in organized ways, forming the foundation for how you will work with data throughout your career. Lists hold ordered sequences of items that you can modify. Tuples hold ordered sequences that remain fixed once created. Dictionaries store key-value pairs that let you look up information by meaningful labels rather than numeric positions. Understanding when to use each structure and how to manipulate them efficiently separates beginners who struggle with data from those who handle it confidently.

These structures appear everywhere in data science work. Before you even encounter pandas DataFrames, you will use lists to store measurements, dictionaries to organize parameters for machine learning models, and tuples to return multiple values from functions. When you eventually work with pandas, you will recognize that DataFrames themselves build on these fundamental concepts. A DataFrame column behaves much like a list, while accessing rows by labels uses dictionary-like syntax. The time you invest truly understanding lists, tuples, and dictionaries pays dividends throughout your entire data science journey.

This comprehensive guide takes you from your first list through confident mastery of Python’s collection types. You will learn how to create and modify lists to store sequences of related data, when tuples provide better choices than lists despite being less flexible, how dictionaries let you organize data with meaningful keys instead of numeric indexes, and which operations work with each structure and why. You will also discover practical patterns that appear constantly in data science code, common mistakes to avoid, and best practices that make your code both correct and readable. By the end, you will think naturally about which data structure fits each situation you encounter.

Lists: Python’s Versatile Ordered Collections

Lists represent Python’s most flexible and commonly used data structure for storing ordered sequences of items. Think of a list as a container that holds multiple values in a specific order, allowing you to add, remove, or modify items as needed. This flexibility makes lists perfect for datasets that change size, sequences of values you want to process one by one, or any collection where you need to maintain order.

Creating a list uses square brackets with items separated by commas:

ages = [25, 30, 22, 35, 28]

names = ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie", "Diana"]

mixed = [1, "hello", 3.14, True] # Lists can hold different types

empty = [] # Empty list to fill laterLists can contain any type of data, including other lists, which creates nested structures useful for representing more complex information:

matrix = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

survey_responses = [["Alice", 25, "Boston"], ["Bob", 30, "Seattle"]]Accessing individual items from a list uses square brackets with the position index, remembering that Python counts from zero:

fruits = ["apple", "banana", "cherry", "date"]

first = fruits[0] # "apple"

second = fruits[1] # "banana"

last = fruits[-1] # "date" - negative indexes count from end

second_last = fruits[-2] # "cherry"This indexing feels identical to how you accessed individual characters in strings because strings and lists share many behaviors as ordered sequences.

Modifying list items involves assigning new values to specific positions:

prices = [10.99, 15.50, 8.75]

prices[0] = 12.99 # Change first price

prices[-1] = 9.00 # Change last price

print(prices) # [12.99, 15.50, 9.0]This ability to modify lists in place distinguishes them from strings and tuples, which cannot be changed after creation.

Adding items to lists uses several methods depending on where you want to add them:

numbers = [1, 2, 3]

# Add single item to end

numbers.append(4)

print(numbers) # [1, 2, 3, 4]

# Add multiple items to end

numbers.extend([5, 6, 7])

print(numbers) # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

# Insert item at specific position

numbers.insert(0, 0) # Insert 0 at beginning

print(numbers) # [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]The difference between append() and extend() trips up many beginners. Append adds its argument as a single item, even if that argument is a list. Extend adds each item from the provided list individually:

list1 = [1, 2, 3]

list1.append([4, 5]) # Adds the entire list as one item

print(list1) # [1, 2, 3, [4, 5]]

list2 = [1, 2, 3]

list2.extend([4, 5]) # Adds each item separately

print(list2) # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]Removing items from lists provides multiple approaches:

colors = ["red", "green", "blue", "yellow", "green"]

# Remove first occurrence of specific value

colors.remove("green")

print(colors) # ["red", "blue", "yellow", "green"]

# Remove and return item at specific position

removed = colors.pop(0) # Removes and returns "red"

print(colors) # ["blue", "yellow", "green"]

# Remove by position using del

del colors[1] # Removes "yellow"

print(colors) # ["blue", "green"]

# Clear entire list

colors.clear()

print(colors) # []Finding information about lists uses built-in functions and methods:

numbers = [3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9, 2, 6]

length = len(numbers) # 8 - number of items

maximum = max(numbers) # 9 - largest value

minimum = min(numbers) # 1 - smallest value

total = sum(numbers) # 31 - sum of all values

index_of_four = numbers.index(4) # 2 - position of first 4

count_of_one = numbers.count(1) # 2 - how many times 1 appearsChecking if an item exists in a list uses the in operator:

fruits = ["apple", "banana", "cherry"]

has_apple = "apple" in fruits # True

has_grape = "grape" in fruits # False

if "banana" in fruits:

print("We have bananas!")Sorting lists can happen in two ways: sorting in place or creating a new sorted version:

numbers = [3, 1, 4, 1, 5]

# Sort in place - modifies the original list

numbers.sort()

print(numbers) # [1, 1, 3, 4, 5]

# Create new sorted list - original unchanged

original = [3, 1, 4, 1, 5]

sorted_version = sorted(original)

print(original) # [3, 1, 4, 1, 5] - unchanged

print(sorted_version) # [1, 1, 3, 4, 5]Reversing lists works similarly:

letters = ["a", "b", "c", "d"]

# Reverse in place

letters.reverse()

print(letters) # ["d", "c", "b", "a"]

# Or create reversed version

original = ["a", "b", "c", "d"]

reversed_version = list(reversed(original))

print(reversed_version) # ["d", "c", "b", "a"]Slicing lets you extract portions of lists using start and end positions separated by colon:

numbers = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

first_five = numbers[0:5] # [0, 1, 2, 3, 4] - items 0 through 4

middle = numbers[3:7] # [3, 4, 5, 6] - items 3 through 6

last_three = numbers[-3:] # [7, 8, 9] - last three items

all_but_first = numbers[1:] # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

all_but_last = numbers[:-1] # [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]The slice notation [start:end] includes the start position but excludes the end position, which takes practice to internalize but becomes natural with use.

Lists in data science commonly store measurements, observations, or features. For example, collecting temperature readings throughout a day:

temperatures = [72, 75, 78, 82, 85, 83, 79, 76]

# Calculate statistics

average = sum(temperatures) / len(temperatures)

highest = max(temperatures)

lowest = min(temperatures)

print(f"Average: {average:.1f}°F")

print(f"Range: {lowest}°F to {highest}°F")Or storing multiple observations for a single subject:

# Patient measurements: [age, height_cm, weight_kg, blood_pressure_systolic]

patient_data = [45, 175, 82, 128]

age = patient_data[0]

height = patient_data[1]

weight = patient_data[2]

bp = patient_data[3]

bmi = weight / ((height / 100) ** 2)

print(f"Patient BMI: {bmi:.1f}")Tuples: Immutable Ordered Collections

Tuples resemble lists in storing ordered sequences of items, but with one critical difference: once created, tuples cannot be modified. This immutability might seem like a limitation, but it provides important benefits including protection against accidental changes, slightly better performance, and the ability to use tuples as dictionary keys where lists cannot serve.

Creating tuples uses parentheses instead of square brackets:

coordinates = (40.7128, -74.0060) # Latitude, longitude

rgb_color = (255, 128, 0) # Red, green, blue values

person = ("Alice", 30, "Engineer") # Name, age, occupationFor single-item tuples, you must include a trailing comma to distinguish them from simple parentheses:

not_a_tuple = (5) # This is just the number 5

actual_tuple = (5,) # This is a tuple containing 5Accessing tuple items works identically to lists:

point = (10, 20, 30)

x = point[0] # 10

y = point[1] # 20

z = point[2] # 30Attempting to modify tuples produces errors:

coordinates = (40.7128, -74.0060)

coordinates[0] = 50 # TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignmentThis immutability guarantees that tuples remain constant throughout your program, preventing bugs where you accidentally modify data that should stay fixed.

Tuple unpacking provides elegant syntax for assigning multiple variables at once:

# Instead of accessing by index

point = (10, 20, 30)

x = point[0]

y = point[1]

z = point[2]

# Use unpacking for cleaner code

point = (10, 20, 30)

x, y, z = point # x=10, y=20, z=30This pattern appears constantly in data science when functions return multiple values:

def get_statistics(numbers):

total = sum(numbers)

count = len(numbers)

average = total / count

return total, count, average # Returns a tuple

# Unpack the returned values

sum_val, count_val, avg_val = get_statistics([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])Tuples excel at representing fixed structures like coordinates, RGB colors, or database records where the number and meaning of positions never change. Lists work better for variable-length collections like measurements over time or sets of observations where you might add or remove items.

Most list operations that do not modify the list also work with tuples:

numbers = (3, 1, 4, 1, 5)

length = len(numbers) # 5

maximum = max(numbers) # 5

total = sum(numbers) # 14

index = numbers.index(4) # 2

count = numbers.count(1) # 2

contains = 1 in numbers # TrueYou can concatenate tuples to create new ones, though this does not modify the originals:

tuple1 = (1, 2, 3)

tuple2 = (4, 5, 6)

combined = tuple1 + tuple2 # (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)Converting between lists and tuples happens easily when you need flexibility or immutability:

# List to tuple

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

my_tuple = tuple(my_list) # (1, 2, 3)

# Tuple to list

my_tuple = (4, 5, 6)

my_list = list(my_tuple) # [4, 5, 6]In data science, tuples commonly represent fixed structures like geographical coordinates, RGB color values, or dimensions:

# Geographic point

location = (42.3601, -71.0589) # Boston coordinates

lat, lon = location

# Image dimensions

image_shape = (1920, 1080, 3) # Width, height, color channels

width, height, channels = image_shape

# Statistical summary that should not change

summary = (100, 75.5, 12.3) # Count, mean, std_dev

n, mean, std = summaryDictionaries: Key-Value Pair Collections

Dictionaries represent Python’s implementation of associative arrays, storing data as pairs of keys and values rather than ordered sequences. Instead of accessing items by numeric position, you access them using meaningful keys, making dictionaries perfect for representing structured data like database records, configuration settings, or any information naturally organized by labels rather than order.

Creating dictionaries uses curly braces with key-value pairs separated by colons:

person = {

"name": "Alice",

"age": 30,

"city": "Boston"

}

prices = {

"apple": 0.99,

"banana": 0.59,

"orange": 1.29

}

empty = {} # Empty dictionaryKeys can be strings, numbers, or tuples, but not lists or other dictionaries:

# Different key types

mixed_keys = {

"name": "Value with string key",

42: "Value with number key",

(1, 2): "Value with tuple key"

}Accessing values uses square brackets with the key:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

name = person["name"] # "Alice"

age = person["age"] # 30Attempting to access a non-existent key raises an error:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30}

country = person["country"] # KeyError: 'country'The get() method provides safer access, returning None or a default value for missing keys:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30}

country = person.get("country") # Returns None

country = person.get("country", "USA") # Returns "USA" as defaultAdding or modifying values uses assignment:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30}

# Add new key-value pair

person["city"] = "Boston"

# Modify existing value

person["age"] = 31

print(person) # {"name": "Alice", "age": 31, "city": "Boston"}Removing items provides several approaches:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

# Remove and return value

age = person.pop("age") # Returns 30, removes from dictionary

# Remove key (without returning value)

del person["city"]

# Clear entire dictionary

person.clear()Checking if a key exists uses the in operator:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30}

has_name = "name" in person # True

has_city = "city" in person # False

if "email" not in person:

person["email"] = "alice@example.com"Getting all keys, values, or pairs from a dictionary:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

# Get all keys

keys = person.keys() # dict_keys(['name', 'age', 'city'])

# Get all values

values = person.values() # dict_values(['Alice', 30, 'Boston'])

# Get all key-value pairs

items = person.items() # dict_items([('name', 'Alice'), ('age', 30), ('city', 'Boston')])These methods return special view objects that reflect the dictionary’s current state. Convert them to lists if you need to modify them or use them multiple times:

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

keys_list = list(person.keys()) # ['name', 'age', 'city']Dictionaries maintain insertion order as of Python 3.7, though you typically choose dictionaries for their key-based access rather than ordering guarantees.

Merging dictionaries combines their key-value pairs:

dict1 = {"a": 1, "b": 2}

dict2 = {"c": 3, "d": 4}

# Modern Python (3.9+)

merged = dict1 | dict2 # {'a': 1, 'b': 2, 'c': 3, 'd': 4}

# Or using update

dict1.update(dict2) # Modifies dict1 in placeWhen merging dictionaries with overlapping keys, the second dictionary’s values overwrite the first:

dict1 = {"a": 1, "b": 2}

dict2 = {"b": 3, "c": 4}

merged = dict1 | dict2 # {'a': 1, 'b': 3, 'c': 4} - b from dict2 winsIn data science, dictionaries excel at organizing heterogeneous data:

# Survey response

response = {

"respondent_id": "R001",

"age": 34,

"income": 75000,

"city": "Chicago",

"owns_home": True,

"satisfaction_score": 8

}

# Model parameters

model_params = {

"learning_rate": 0.01,

"max_depth": 5,

"n_estimators": 100,

"random_state": 42

}

# Aggregated statistics

city_stats = {

"Boston": {"population": 694583, "median_income": 71834},

"Chicago": {"population": 2746388, "median_income": 62097},

"Seattle": {"population": 753675, "median_income": 102486}

}Dictionaries also organize categorical counts or frequencies:

# Count survey responses

responses = ["yes", "no", "yes", "yes", "maybe", "no", "yes"]

counts = {}

for response in responses:

if response in counts:

counts[response] += 1

else:

counts[response] = 1

print(counts) # {"yes": 4, "no": 2, "maybe": 1}Choosing the Right Data Structure

Understanding when to use lists versus tuples versus dictionaries comes with practice, but some guidelines help you make good choices from the beginning.

Use lists when you have ordered collections that might change size or content, you need to access items by position, you will sort or reverse the collection, or you plan to add or remove items frequently. Lists work well for measurements over time, sets of observations, or any sequence where order matters and flexibility is needed:

# Good use of lists

temperatures = [72, 75, 78, 82, 85]

student_names = ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"]

measurements = [] # Will add items as collectedUse tuples when you have fixed structures that should not change, you want to protect data from accidental modification, you need to use the collection as a dictionary key, or you are returning multiple values from a function. Tuples work well for coordinates, RGB colors, database records, or any fixed-size structure:

# Good use of tuples

coordinates = (42.3601, -71.0589)

rgb = (255, 128, 0)

def analyze_data(values):

return (len(values), sum(values), max(values)) # Multiple return valuesUse dictionaries when you need to look up values by meaningful keys rather than positions, you have heterogeneous data with different types and meanings, or you are counting or grouping items. Dictionaries work well for configuration settings, structured records, parameters, or any data naturally organized by labels:

# Good use of dictionaries

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

model_config = {"learning_rate": 0.01, "max_depth": 5}

word_counts = {"python": 15, "data": 22, "science": 18}Sometimes you will nest these structures for more complex data:

# List of dictionaries - common for tabular data

students = [

{"name": "Alice", "age": 20, "gpa": 3.8},

{"name": "Bob", "age": 22, "gpa": 3.5},

{"name": "Charlie", "age": 21, "gpa": 3.9}

]

# Dictionary of lists - grouping related sequences

city_data = {

"temperatures": [72, 75, 78, 82],

"humidity": [65, 70, 68, 72],

"dates": ["2024-01-01", "2024-01-02", "2024-01-03", "2024-01-04"]

}Common Operations and Patterns

Certain patterns appear repeatedly in data science code. Learning to recognize and use them makes your code more readable and efficient.

Iterating through collections processes each item in sequence. You will learn loops in detail in upcoming articles, but here are preview patterns:

# Iterating through lists

temperatures = [72, 75, 78, 82, 85]

for temp in temperatures:

print(f"Temperature: {temp}°F")

# Iterating through dictionary keys

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "Boston"}

for key in person:

print(f"{key}: {person[key]}")

# Iterating through dictionary key-value pairs

for key, value in person.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}")List comprehensions provide concise syntax for creating new lists based on existing ones:

# Convert temperatures from Fahrenheit to Celsius

fahrenheit = [32, 68, 86, 104]

celsius = [(f - 32) * 5/9 for f in fahrenheit]

# Result: [0.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0]

# Filter values

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

evens = [n for n in numbers if n % 2 == 0]

# Result: [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]Dictionary comprehensions work similarly:

# Square numbers

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

squares = {n: n**2 for n in numbers}

# Result: {1: 1, 2: 4, 3: 9, 4: 16, 5: 25}Combining and splitting collections:

# Combine lists

list1 = [1, 2, 3]

list2 = [4, 5, 6]

combined = list1 + list2 # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

# Split lists

full_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

first_half = full_list[:3] # [1, 2, 3]

second_half = full_list[3:] # [4, 5, 6]Common Mistakes and Best Practices

Avoiding common pitfalls accelerates your learning and prevents frustrating bugs.

Forgetting that lists are mutable can cause unexpected behavior:

# Dangerous - both variables point to same list

original = [1, 2, 3]

reference = original # Does not create a copy!

reference.append(4)

print(original) # [1, 2, 3, 4] - original changed too!

# Safe - create actual copy

original = [1, 2, 3]

copy = original.copy() # or list(original)

copy.append(4)

print(original) # [1, 2, 3] - unchangedModifying lists while iterating over them produces unpredictable results:

# Wrong - don't modify list during iteration

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

for num in numbers:

if num % 2 == 0:

numbers.remove(num) # Dangerous!

# Right - create new list instead

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

odds = [num for num in numbers if num % 2 != 0]Using lists as default function arguments creates subtle bugs:

# Dangerous - default list is shared across calls

def add_item(item, my_list=[]):

my_list.append(item)

return my_list

print(add_item(1)) # [1]

print(add_item(2)) # [1, 2] - unexpected!

# Safe - use None as default

def add_item(item, my_list=None):

if my_list is None:

my_list = []

my_list.append(item)

return my_listAccessing non-existent dictionary keys without checking:

# Risky

person = {"name": "Alice"}

city = person["city"] # KeyError!

# Safe

city = person.get("city", "Unknown")Conclusion

Lists, tuples, and dictionaries form the foundation of how you organize and work with data in Python. Every dataset you analyze, every model you build, and every result you process involves these fundamental structures. Lists provide flexible ordered sequences for collections that change. Tuples offer immutable sequences for fixed structures. Dictionaries enable key-based access for structured data with meaningful labels. Understanding when to use each structure and how to manipulate them efficiently makes the difference between struggling with data and handling it confidently.

As you progress in data science, you will work with pandas DataFrames that build directly on these concepts. DataFrame columns behave like lists, rows can be accessed like dictionaries, and many operations mirror what you have learned here. NumPy arrays extend list-like structures with powerful mathematical operations. The patterns you learn with these basic structures transfer directly to these more specialized tools.

Practice working with lists, tuples, and dictionaries through small programs that create, modify, and combine them in different ways. The operations that feel awkward initially become second nature with repetition. Build the muscle memory now, and these fundamental operations will flow naturally when you tackle real data science problems. The investment you make in truly understanding these structures pays dividends throughout your entire career.