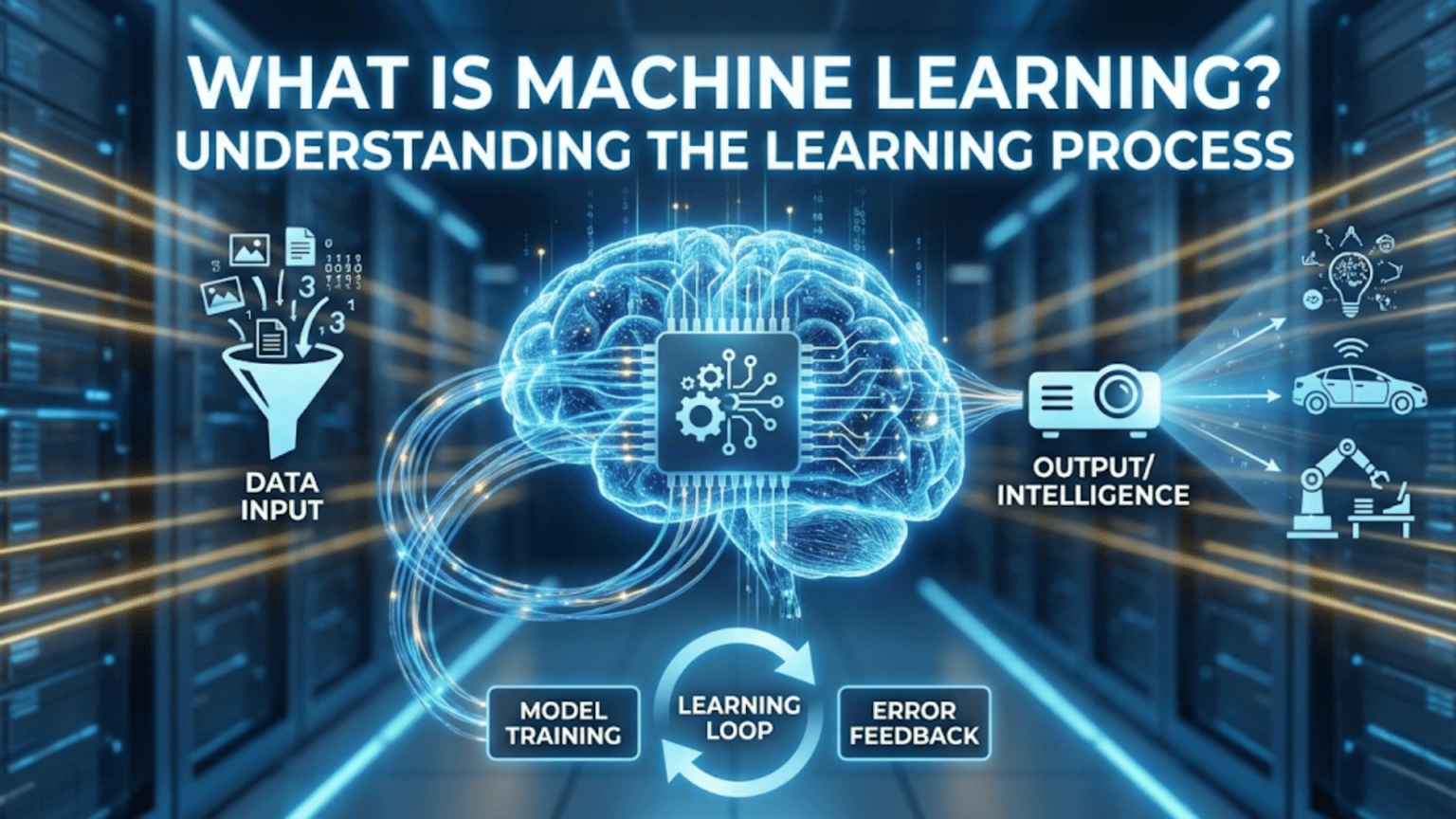

Machine learning is a subset of artificial intelligence that enables computer systems to learn and improve from experience without being explicitly programmed. Instead of following pre-written instructions, machine learning algorithms identify patterns in data and use those patterns to make predictions or decisions on new, unseen data.

Introduction: The Revolution of Self-Learning Systems

Imagine teaching a child to recognize different animals. You don’t provide them with a comprehensive rulebook defining every characteristic of every creature. Instead, you show them examples—pictures of dogs, cats, birds, and fish—and gradually, through exposure and correction, they learn to identify animals on their own. This is essentially how machine learning works, except instead of a child, we’re teaching a computer system.

Machine learning represents one of the most transformative technological advances of our time. It’s the driving force behind recommendation systems that suggest your next favorite show on Netflix, voice assistants that understand your spoken commands, spam filters that protect your inbox, and autonomous vehicles that navigate city streets. Yet despite its prevalence in our daily lives, machine learning remains a mystery to many people.

This article will demystify machine learning, breaking down complex concepts into understandable pieces while providing you with a comprehensive understanding of how computers learn from data. Whether you’re a curious beginner, a business professional looking to leverage machine learning, or someone considering a career in this field, this guide will equip you with the foundational knowledge you need.

Understanding the Core Concept: What Exactly is Machine Learning?

At its most fundamental level, machine learning is about creating systems that can learn and improve from experience. Traditional computer programs operate based on explicit instructions: if this condition is met, do that action. These rule-based systems work well for clearly defined tasks, but they falter when dealing with complex, nuanced problems where rules are difficult to articulate.

Machine learning takes a different approach. Instead of programming explicit rules, we provide the system with data and allow it to discover patterns and relationships on its own. The computer develops its own understanding of the task through exposure to examples, much like humans learn through experience.

Consider the task of recognizing handwritten digits. Writing explicit rules for this task would be incredibly challenging. What makes a “3” different from an “8”? How do you account for different handwriting styles, angles, and variations? Traditional programming would require you to manually specify countless rules and conditions. Machine learning, however, allows the computer to examine thousands of examples of handwritten digits and learn the distinguishing characteristics on its own.

The term “machine learning” was coined by Arthur Samuel in 1959, when he defined it as the “field of study that gives computers the ability to learn without being explicitly programmed.” This definition remains remarkably relevant today, capturing the essence of what makes machine learning powerful: the ability to improve performance through experience rather than through manual programming.

The Evolution: From Traditional Programming to Machine Learning

To truly appreciate machine learning, it helps to understand how it differs from traditional programming approaches. This distinction is fundamental to grasping why machine learning has become so essential in modern technology.

Traditional Programming Approach

In traditional programming, human programmers write explicit instructions for every scenario the program might encounter. The process follows this pattern:

Input (Data) + Program (Rules) = Output (Answers)

For example, if you wanted to create a spam email detector using traditional programming, you would need to manually specify rules such as:

- If the email contains the word “viagra” more than once, mark as spam

- If the sender’s address is not in the contact list and the email contains more than five exclamation marks, mark as spam

- If the email subject contains “WINNER” in all caps, mark as spam

This approach works for simple, well-defined problems. However, it becomes impractical as complexity increases. Spammers constantly evolve their tactics, rendering hard-coded rules obsolete. Maintaining such a system requires constant manual updates, and capturing every possible variation is virtually impossible.

Machine Learning Approach

Machine learning flips this paradigm on its head. Instead of programming rules, we provide examples and let the system learn the patterns:

Input (Data) + Output (Answers) = Program (Rules)

Using the spam detection example, instead of writing rules, we would:

- Collect thousands of emails that have been labeled as “spam” or “not spam”

- Feed these labeled examples to a machine learning algorithm

- Let the algorithm identify patterns that distinguish spam from legitimate emails

- Use the learned patterns to classify new, unseen emails

The machine learning system might discover patterns that humans never explicitly considered: certain combinations of words, email length, sender patterns, time of day, or subtle linguistic markers. It can also adapt as spam tactics evolve, continuously learning from new examples.

This fundamental shift—from explicit programming to learning from examples—is what makes machine learning so powerful for complex, evolving problems.

The Anatomy of Machine Learning: Key Components

Understanding machine learning requires familiarity with its essential components. These building blocks work together to create systems that can learn and make predictions.

Data: The Foundation of Learning

Data is the lifeblood of machine learning. Without data, there is no learning. The quality, quantity, and relevance of your data directly impact how well your machine learning system will perform.

Data in machine learning typically comes in the form of examples or observations. Each example contains features (input variables) and, in many cases, a label or target (the output you want to predict). For instance, in a house price prediction system:

- Features might include square footage, number of bedrooms, location, age of the property, and school district quality

- Label would be the actual selling price of the house

The process of learning involves examining many such examples and discovering relationships between features and labels. The more representative and diverse your data, the better your model can generalize to new situations.

Algorithms: The Learning Mechanisms

Machine learning algorithms are the mathematical procedures that enable computers to learn from data. Think of them as different teaching methods—some work better for certain types of problems than others.

There are dozens of machine learning algorithms, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Some popular ones include:

- Linear Regression: Finds linear relationships between inputs and outputs

- Decision Trees: Creates a tree-like model of decisions based on feature values

- Neural Networks: Mimics the structure of biological brains to recognize complex patterns

- Support Vector Machines: Finds optimal boundaries between different categories

- K-Nearest Neighbors: Makes predictions based on similarity to nearby examples

The choice of algorithm depends on factors like the nature of your problem, the type and amount of data available, computational resources, and the desired accuracy and interpretability of results.

Models: The Learned Knowledge

A model is what results from applying a machine learning algorithm to data. It’s the actual learned representation of patterns in your data. You can think of the model as the “program” that the machine learning process creates.

The model encapsulates the knowledge extracted from training data and can be used to make predictions on new data. For example, after training on thousands of house sales, your model “knows” how features like square footage and location typically relate to price, even for houses it has never seen before.

Models can be simple or complex. A simple linear regression model might be represented by a single equation with a few parameters. A deep neural network might contain millions of parameters organized in intricate layers. The complexity of the model should match the complexity of the problem—simpler is often better when it works.

Features: The Input Variables

Features are the individual measurable properties or characteristics used to make predictions. Feature engineering—the process of selecting, creating, and transforming features—is often one of the most important steps in building effective machine learning systems.

Good features should be:

- Relevant: Actually related to what you’re trying to predict

- Informative: Provide useful signal, not just noise

- Independent: Ideally not redundant with other features

- Measurable: Can be consistently quantified or categorized

For a customer churn prediction system, features might include:

- Account age

- Number of customer service contacts

- Average monthly spending

- Number of products owned

- Time since last purchase

- Engagement with marketing emails

Creating effective features often requires domain expertise—understanding the problem well enough to identify which factors are likely to be predictive.

The Machine Learning Process: How Systems Actually Learn

Now that we understand the components, let’s examine the actual process by which machine learning systems learn. This process, while it can vary depending on the specific approach, generally follows a common pattern.

Step 1: Problem Definition

Every machine learning project begins with clearly defining what you want to achieve. This involves:

- Identifying the specific problem you want to solve

- Determining what type of prediction or decision you need

- Establishing success criteria and metrics

- Understanding constraints like available data, computational resources, and deployment requirements

For example, you might define a problem as: “Predict which customers are likely to cancel their subscription in the next 30 days, with at least 80% accuracy, to enable targeted retention campaigns.”

Step 2: Data Collection and Preparation

Once the problem is defined, you need to gather relevant data. This often involves:

- Collecting data from various sources (databases, APIs, files, sensors)

- Combining data from different sources

- Handling missing values

- Removing or correcting erroneous data

- Converting data into suitable formats

- Creating or engineering relevant features

Data preparation typically consumes 60-80% of the time in a machine learning project. It’s tedious but crucial—garbage in, garbage out. The quality of your data fundamentally limits the quality of your model.

Step 3: Exploratory Data Analysis

Before building models, data scientists explore and understand their data through:

- Statistical summaries (means, medians, ranges)

- Visualizations (histograms, scatter plots, correlation matrices)

- Identifying patterns, trends, and anomalies

- Understanding relationships between variables

- Detecting potential biases or imbalances

This exploration helps inform subsequent decisions about feature engineering, algorithm selection, and model configuration.

Step 4: Model Selection and Training

This is where the actual learning happens. The process involves:

Selecting an appropriate algorithm based on the problem type, data characteristics, and requirements.

Splitting the data typically into three sets:

- Training set (usually 60-70%): Used to train the model

- Validation set (usually 15-20%): Used to tune model parameters and make decisions during development

- Test set (usually 15-20%): Used only at the end to evaluate final performance

Training the model by feeding it the training data and allowing the algorithm to adjust its internal parameters to minimize errors. This is an iterative process where the algorithm:

- Makes predictions on training examples

- Compares predictions to actual values

- Calculates the error or loss

- Adjusts parameters to reduce the error

- Repeats until the error stops decreasing significantly

The specific mechanics vary by algorithm, but the general principle remains the same: learn patterns that minimize prediction errors on the training data.

Step 5: Model Evaluation

After training, you evaluate how well the model performs on data it hasn’t seen before (the test set). This reveals whether the model has truly learned generalizable patterns or merely memorized the training data.

Common evaluation metrics include:

- Accuracy: Percentage of correct predictions

- Precision: Of all positive predictions, how many were actually positive?

- Recall: Of all actual positives, how many did we identify?

- F1 Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall

- Mean Squared Error: Average squared difference between predictions and actual values

- ROC-AUC: Ability to distinguish between classes across different thresholds

The choice of metric depends on the specific problem and what matters most in your application.

Step 6: Model Tuning and Optimization

If the initial model doesn’t perform well enough, you iterate:

- Adjust hyperparameters (configuration settings of the algorithm)

- Try different algorithms

- Engineer new features or transform existing ones

- Collect more or better data

- Address overfitting or underfitting issues

This iterative refinement continues until you achieve satisfactory performance or determine that the problem requires a different approach.

Step 7: Deployment and Monitoring

Once you have a well-performing model, it needs to be deployed into a production environment where it can make predictions on real data. Deployment involves:

- Integrating the model into existing systems or applications

- Setting up infrastructure to serve predictions efficiently

- Creating monitoring systems to track model performance over time

- Establishing processes to update or retrain the model as needed

Machine learning models can degrade over time as the real world changes. Continuous monitoring ensures models remain accurate and effective.

Types of Machine Learning: Different Approaches to Learning

Machine learning encompasses several distinct approaches, each suited to different types of problems. Understanding these categories helps you choose the right approach for your specific needs.

Supervised Learning: Learning from Labeled Examples

Supervised learning is the most common type of machine learning. In supervised learning, the algorithm learns from labeled training data—data where the correct answer is already known.

The process works like learning with a teacher. You show the system examples along with the correct answers, and it learns to map inputs to outputs. Once trained, it can predict outputs for new inputs it hasn’t seen before.

Supervised learning divides into two main categories:

Classification: Predicting categories or classes

- Is this email spam or not spam?

- Will this customer churn or remain?

- What digit is in this image (0-9)?

- Is this tumor benign or malignant?

Regression: Predicting continuous numerical values

- What will be the temperature tomorrow?

- How much will this house sell for?

- What will the stock price be next week?

- How many units will we sell next month?

Common supervised learning algorithms include linear regression, logistic regression, decision trees, random forests, support vector machines, and neural networks.

Unsupervised Learning: Finding Hidden Patterns

In unsupervised learning, the algorithm works with unlabeled data—there are no correct answers provided. Instead, the system tries to find inherent structure, patterns, or groupings in the data on its own.

This is like exploring a new city without a guide. You observe and discover patterns independently: where the restaurants cluster, which neighborhoods are residential, how streets are organized.

Common unsupervised learning tasks include:

Clustering: Grouping similar items together

- Segmenting customers into distinct groups based on behavior

- Organizing news articles by topic

- Identifying different types of network traffic

- Grouping genes with similar expression patterns

Dimensionality Reduction: Simplifying data while preserving important information

- Compressing images while maintaining quality

- Visualizing high-dimensional data

- Removing redundant features

- Noise reduction

Anomaly Detection: Identifying unusual patterns

- Detecting fraudulent transactions

- Identifying network intrusions

- Finding manufacturing defects

- Spotting unusual medical test results

Popular unsupervised learning algorithms include K-means clustering, hierarchical clustering, principal component analysis (PCA), and autoencoders.

Reinforcement Learning: Learning Through Trial and Error

Reinforcement learning takes a different approach. Instead of learning from a dataset, an agent learns by interacting with an environment and receiving feedback in the form of rewards or penalties.

Think of training a dog. You don’t show the dog a dataset of correct and incorrect behaviors. Instead, the dog tries different actions, and you provide rewards (treats, praise) for desired behaviors and corrections for undesired ones. Over time, the dog learns which actions lead to rewards.

In reinforcement learning:

- An agent takes actions in an environment

- Each action affects the state of the environment

- The agent receives rewards or penalties based on its actions

- The goal is to learn a policy—a strategy for choosing actions that maximizes cumulative reward over time

Reinforcement learning has achieved remarkable successes:

- Game-playing AI (defeating world champions in Go, chess, and video games)

- Robotics (teaching robots to walk, manipulate objects, or navigate)

- Autonomous vehicles (learning to drive in complex environments)

- Resource optimization (managing data center cooling, optimizing ad placement)

The key distinction is that reinforcement learning doesn’t require pre-labeled examples. The agent learns what works through experience, making it suitable for problems where the optimal solution isn’t known in advance.

Semi-Supervised and Self-Supervised Learning

These hybrid approaches address the challenge that labeling data is often expensive and time-consuming.

Semi-supervised learning uses a small amount of labeled data combined with a larger amount of unlabeled data. The model learns from the labeled examples and uses its emerging understanding to extract additional insights from the unlabeled data.

This is particularly useful when labels are expensive to obtain. For example, you might have millions of medical images but only hundreds that have been reviewed by specialists. Semi-supervised learning can leverage both.

Self-supervised learning creates its own supervisory signal from the data itself, without requiring human-provided labels. For instance, a language model might learn by predicting the next word in a sentence, using the text itself as both input and target.

These approaches have become increasingly important, enabling models to learn from vast amounts of unlabeled data available on the internet.

Real-World Applications: Machine Learning in Action

Understanding machine learning becomes more concrete when you see how it’s applied to solve real problems. Let’s explore diverse applications across different industries.

Healthcare and Medicine

Machine learning is revolutionizing healthcare through applications like:

Medical Diagnosis: AI systems analyze medical images to detect diseases. For example, machine learning models can identify diabetic retinopathy from retinal scans with accuracy matching or exceeding human specialists. These systems examine thousands of image features invisible to the human eye, catching early warning signs that might be missed.

Drug Discovery: Pharmaceutical companies use machine learning to identify promising drug candidates from millions of potential molecular structures. This dramatically accelerates the traditionally slow and expensive drug development process, potentially bringing life-saving treatments to patients years earlier.

Personalized Treatment: Machine learning models analyze patient data—genetic information, medical history, lifestyle factors—to recommend personalized treatment plans. Rather than one-size-fits-all approaches, doctors can provide treatments optimized for each individual patient’s unique characteristics.

Predictive Healthcare: Hospitals use machine learning to predict which patients are at risk of readmission, allowing healthcare providers to intervene proactively with additional support and monitoring.

Finance and Banking

The financial sector extensively leverages machine learning for:

Fraud Detection: Credit card companies analyze billions of transactions in real-time, using machine learning to identify suspicious patterns that might indicate fraud. The system learns from historical fraud cases and adapts to new fraud tactics as they emerge, protecting both consumers and financial institutions.

Credit Scoring: Rather than relying solely on traditional credit scores, lenders use machine learning models that consider hundreds of factors to assess creditworthiness. This enables more accurate risk assessment and can expand access to credit for underserved populations.

Algorithmic Trading: Investment firms use machine learning to identify profitable trading opportunities by analyzing market data, news, social media sentiment, and countless other signals. These systems can process information and execute trades far faster than human traders.

Risk Assessment: Banks use machine learning to evaluate various risks—credit risk, market risk, operational risk—helping them make better-informed decisions about lending, investments, and regulatory compliance.

E-Commerce and Retail

Online shopping experiences are heavily powered by machine learning:

Recommendation Systems: When Amazon suggests products you might like or Netflix recommends shows, that’s machine learning analyzing your past behavior, similar users’ preferences, and product characteristics to predict what you’ll enjoy. These systems dramatically increase sales and user engagement.

Dynamic Pricing: Retailers use machine learning to optimize prices in real-time based on demand, inventory levels, competitor pricing, time of day, and customer characteristics. Uber’s surge pricing is a prominent example.

Inventory Optimization: Machine learning forecasts product demand, helping retailers maintain optimal inventory levels—enough stock to meet demand without tying up capital in excess inventory or suffering stockouts.

Customer Service Chatbots: AI-powered chatbots handle customer inquiries, learning from past interactions to provide better responses over time. They handle routine questions, freeing human agents for complex issues.

Transportation and Logistics

Machine learning optimizes movement and delivery:

Autonomous Vehicles: Self-driving cars use machine learning to perceive their environment (identifying pedestrians, other vehicles, traffic signs, road conditions) and make driving decisions. These systems learn from millions of miles of driving data.

Route Optimization: Delivery companies like UPS and FedEx use machine learning to determine optimal delivery routes, considering traffic patterns, delivery windows, vehicle capacity, and fuel efficiency. This saves millions of dollars in fuel costs and delivery time.

Predictive Maintenance: Airlines and shipping companies use machine learning to predict when vehicles or equipment need maintenance before failures occur, reducing downtime and preventing dangerous malfunctions.

Demand Forecasting: Ride-sharing services use machine learning to predict where and when demand will spike, positioning drivers accordingly and adjusting pricing to balance supply and demand.

Manufacturing and Industry

Industrial applications include:

Quality Control: Computer vision systems powered by machine learning inspect products on assembly lines, detecting defects more consistently and quickly than human inspectors. This improves product quality and reduces waste.

Predictive Maintenance: Sensors on industrial equipment feed data to machine learning models that predict equipment failures before they occur, scheduling maintenance proactively rather than reactively responding to breakdowns.

Process Optimization: Machine learning optimizes complex manufacturing processes, adjusting parameters in real-time to maximize efficiency, minimize waste, and improve product quality.

Supply Chain Management: Companies use machine learning to forecast demand, optimize inventory across the supply chain, identify potential disruptions, and find more efficient logistics solutions.

Natural Language Processing

Machine learning enables computers to understand and generate human language:

Virtual Assistants: Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant use machine learning to understand spoken commands, interpret intent, and generate appropriate responses or actions.

Machine Translation: Services like Google Translate use machine learning to translate between languages with increasing accuracy, learning from millions of translated documents and continuously improving.

Sentiment Analysis: Companies analyze customer reviews, social media posts, and feedback to understand public sentiment about products, brands, or topics, helping inform business decisions.

Text Summarization: Machine learning can read lengthy documents and generate concise summaries, helping people quickly grasp key information from large volumes of text.

The Machine Learning Workflow: A Practical Example

To make the machine learning process more concrete, let’s walk through a complete example: building a system to predict customer churn for a subscription service.

Problem Definition

Our fictional company, “StreamFlix,” offers a video streaming subscription and wants to predict which customers are likely to cancel their subscription in the next month. Early identification allows the customer retention team to intervene with special offers or support.

Success criteria: Identify at least 70% of customers who will churn, while keeping false alarms (incorrectly predicting churn for customers who will stay) below 30%.

Data Collection

We gather historical data on customers, including:

- Demographics: age, location, account age

- Usage patterns: average hours watched per week, number of logins, content preferences

- Engagement: customer service contacts, app ratings, watchlist size

- Billing: payment method, subscription tier, failed payment attempts

- Historical behavior: past subscription pauses, customer since date

We collect data on 50,000 customers from the past year, including information about whether they eventually churned or remained subscribed.

Data Preparation and Exploration

Examining our data reveals:

- 15% of customers churned (our positive class)

- Some customers have missing values for certain fields

- Usage patterns vary dramatically between weekend and weekday

- The dataset is imbalanced (far more customers stayed than left)

We clean the data by:

- Filling missing values with medians or mode values

- Creating new features: “days since last login,” “viewing hours trend,” “payment issue flag”

- Normalizing numerical features to similar scales

- Encoding categorical variables (like subscription tier) numerically

We split our data: 35,000 examples for training, 7,500 for validation, and 7,500 for final testing.

Model Development

We try several algorithms:

Logistic Regression: A simple baseline model that predicts churn probability based on a weighted combination of features. This achieves 68% recall (finding churners) but 40% false positive rate.

Random Forest: An ensemble of decision trees that considers multiple features and their combinations. This improves to 73% recall with 28% false positives.

Gradient Boosting: A more sophisticated ensemble method that builds trees sequentially, each correcting errors of previous ones. This achieves 76% recall with 25% false positives.

Through the validation set, we tune hyperparameters:

- Number of trees in the forest

- Maximum depth of each tree

- Minimum samples required to split a node

- Learning rate for gradient boosting

Model Evaluation

On our held-out test set, our final gradient boosting model achieves:

- Recall: 75% (we identify 3 out of 4 customers who will churn)

- Precision: 65% (when we predict churn, we’re correct 65% of time)

- F1 Score: 0.70

We analyze which features matter most:

- Days since last login (most predictive)

- Declining trend in viewing hours

- Customer service contacts about billing

- Failed payment attempts

- Time spent browsing vs. watching

This reveals that engagement decline and payment issues are the strongest churn signals.

Insights and Actions

Beyond predictions, the model provides actionable insights:

- Customers who haven’t logged in for 7+ days have 3x higher churn risk

- Payment failures are followed by 60% churn rate within two weeks

- Customers contacting support about billing issues churn at 45% rate

StreamFlix’s retention team uses these insights to:

- Send personalized content recommendations to inactive users

- Proactively contact customers after payment failures to offer payment plan adjustments

- Train support staff to identify and address billing concerns more effectively

- Create targeted retention offers for high-risk customers

Monitoring and Iteration

After deployment, the data science team monitors:

- Model accuracy over time (does it remain effective?)

- Concept drift (are customer behaviors changing?)

- Business impact (are retention efforts working?)

- Bias and fairness (does the model treat all customer segments fairly?)

Every quarter, they retrain the model with fresh data, incorporating new patterns and behaviors. They also experiment with new features and algorithms, continuously improving the system.

This example illustrates the complete machine learning workflow from problem to solution, showing how data-driven insights translate into business value.

Key Challenges in Machine Learning

While machine learning is powerful, it faces several significant challenges that practitioners must navigate.

Data Quality and Quantity

Machine learning models are only as good as their training data. Challenges include:

Insufficient Data: Many algorithms require thousands or millions of examples to learn effectively. In specialized domains like rare disease diagnosis, sufficient data may simply not exist.

Biased Data: If training data isn’t representative of the real world, models learn and perpetuate those biases. For example, facial recognition systems trained predominantly on certain demographic groups perform poorly on others.

Noisy or Mislabeled Data: Errors in training data lead to models learning incorrect patterns. Even small percentages of mislabeled data can significantly degrade performance.

Data Privacy: Using personal data for machine learning raises privacy concerns. Regulations like GDPR restrict how data can be collected and used, limiting available training data.

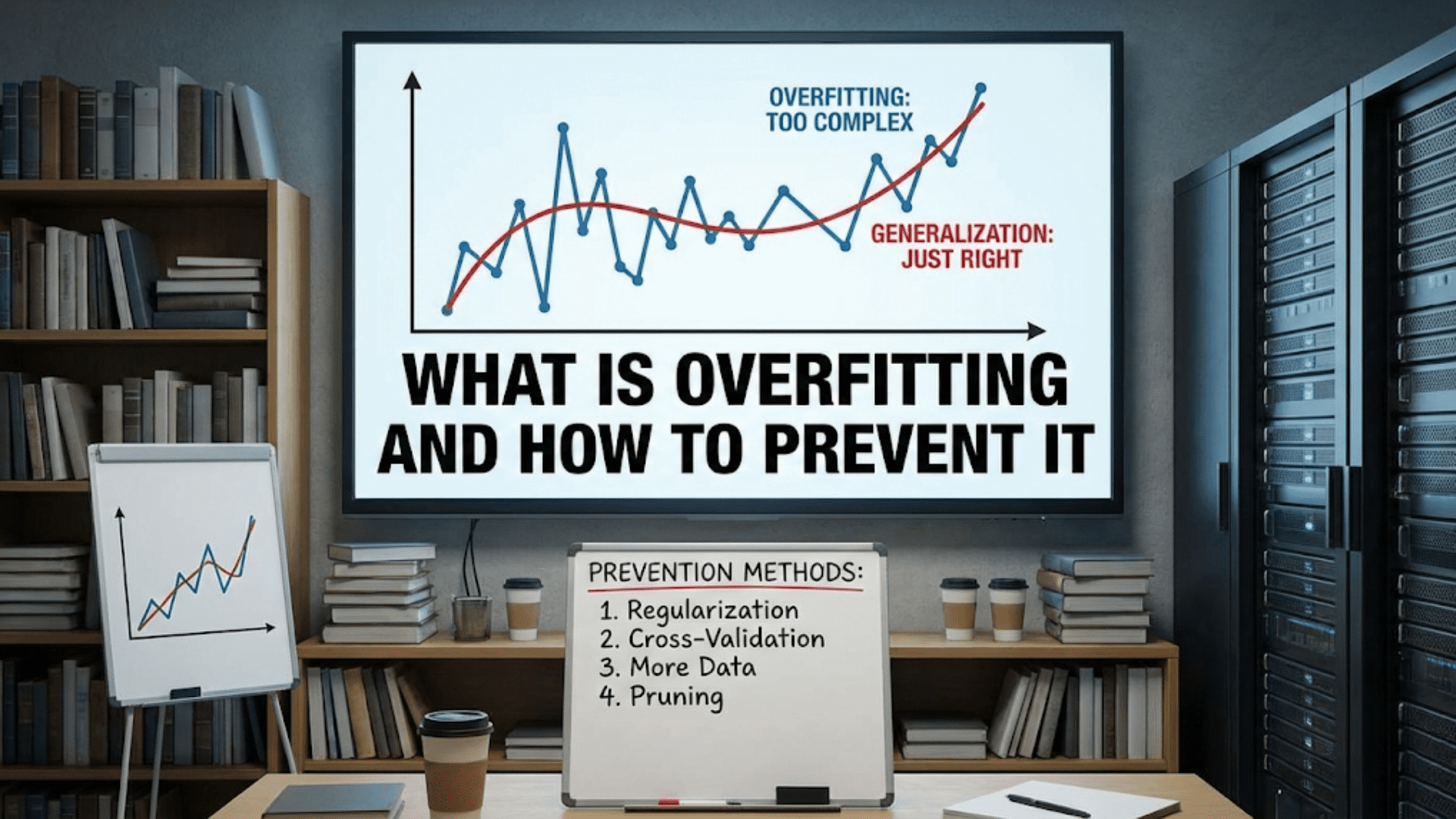

Overfitting and Generalization

A model might perform excellently on training data but poorly on new data—this is overfitting. The model has essentially memorized the training examples rather than learning generalizable patterns.

It’s like a student who memorizes specific exam questions rather than understanding the underlying concepts. They ace questions they’ve seen before but struggle with variations.

Preventing overfitting requires:

- Using sufficient training data

- Choosing appropriately complex models

- Applying regularization techniques

- Validating on separate data

- Using ensemble methods

The opposite problem, underfitting, occurs when models are too simple to capture relevant patterns. Finding the right balance—models complex enough to capture patterns but simple enough to generalize—is a central challenge.

Interpretability and Explainability

Many powerful machine learning models, particularly deep neural networks, are “black boxes”—they make accurate predictions but don’t provide understandable explanations for their decisions.

This creates problems in high-stakes domains. If a model denies someone a loan, they deserve to know why. If a medical AI recommends a treatment, doctors need to understand the reasoning. If an autonomous vehicle makes a dangerous decision, we need to diagnose what went wrong.

The field of explainable AI (XAI) develops techniques to make models more interpretable, but this often involves trade-offs with accuracy. Simpler, more interpretable models may perform worse than complex black-box models.

Computational Resources

Training sophisticated machine learning models, particularly deep learning models, requires substantial computational power. State-of-the-art language models like GPT-4 require millions of dollars in computing resources to train.

This creates barriers:

- Cost: Not all organizations can afford the necessary hardware

- Energy: Training large models consumes enormous amounts of electricity

- Expertise: Managing distributed computing infrastructure requires specialized skills

- Time: Even with powerful hardware, training can take days or weeks

Edge deployment presents additional challenges—running models on resource-constrained devices like smartphones or IoT sensors.

Concept Drift and Model Degradation

The world changes, and with it, the patterns machine learning models rely on. A model trained on 2020 data may perform poorly in 2024 because customer behaviors, market conditions, or other factors have evolved.

This “concept drift” requires:

- Continuous monitoring of model performance

- Regular retraining with fresh data

- Adaptive systems that detect and respond to changes

- Mechanisms to quickly update deployed models

Adversarial Attacks

Machine learning models can be fooled by carefully crafted inputs. Adversarial examples—inputs deliberately designed to cause misclassification—can trick even highly accurate models.

For instance, researchers have shown that adding carefully designed, nearly invisible noise to images can cause image classifiers to make wildly incorrect predictions. This raises security concerns, especially in critical applications like autonomous vehicles or security systems.

Comparison: Machine Learning vs. Traditional Programming vs. Deep Learning

To clarify machine learning’s position in the broader landscape, let’s compare it with related approaches:

| Aspect | Traditional Programming | Machine Learning | Deep Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach | Explicit rules written by programmers | Rules learned from data | Hierarchical patterns learned through neural networks |

| Best For | Well-defined, rule-based tasks | Complex pattern recognition with available training data | Very complex patterns (images, speech, text) with massive datasets |

| Data Requirements | Minimal—just enough to test rules | Moderate to large datasets (thousands to millions of examples) | Very large datasets (millions+ examples) or sophisticated architectures |

| Adaptability | Low—requires manual updates | High—learns from new data | Very high—can transfer learning across domains |

| Interpretability | Very high—logic is explicit | Variable—depends on algorithm | Low—complex internal representations |

| Development Time | Can be quick for simple tasks | Moderate—requires data preparation and training | Longer—requires architecture design and extensive training |

| Computational Needs | Low—runs on any device | Moderate—depends on algorithm complexity | Very high—often requires GPUs or specialized hardware |

| Maintenance | High—manual updates needed | Moderate—requires monitoring and retraining | Moderate to high—complex systems require expertise |

| Examples | Calculator, word processor, basic database queries | Spam detection, recommendation systems, fraud detection | Image recognition, natural language understanding, game playing |

Deep learning is a subset of machine learning using neural networks with multiple layers. It excels at tasks traditional machine learning struggles with but requires more data and computational resources. The choice depends on your specific problem, available resources, and requirements.

Getting Started: Your Path to Learning Machine Learning

If you’re interested in pursuing machine learning, here’s a practical roadmap:

Foundational Knowledge

Mathematics: While you don’t need a PhD, understanding these areas helps:

- Linear algebra (vectors, matrices, operations)

- Calculus (derivatives, gradients)

- Probability and statistics (distributions, hypothesis testing)

- Basic optimization concepts

Don’t let math intimidate you—start with the basics and learn more as needed. Many successful practitioners learn mathematics alongside machine learning, gaining intuition through application.

Programming: Python is the standard language for machine learning. Focus on:

- Core Python fundamentals

- NumPy for numerical computing

- Pandas for data manipulation

- Matplotlib/Seaborn for visualization

- Jupyter notebooks for experimentation

Core Machine Learning Concepts

Study fundamental concepts:

- Types of machine learning (supervised, unsupervised, reinforcement)

- The machine learning pipeline

- Model evaluation and validation

- Overfitting and regularization

- Feature engineering

Practical Libraries and Tools

Familiarize yourself with key libraries:

- Scikit-learn: Comprehensive library for traditional machine learning

- TensorFlow or PyTorch: Deep learning frameworks

- Keras: High-level neural network API

- XGBoost: Powerful gradient boosting implementation

Hands-On Practice

Theory matters, but practice is essential:

- Start small: Begin with simple datasets and straightforward problems

- Follow tutorials: Work through structured courses and examples

- Kaggle competitions: Practice on real datasets with community feedback

- Personal projects: Apply machine learning to problems you care about

- Read code: Study implementations from experienced practitioners

Recommended Learning Path

Beginner (0-3 months):

- Python fundamentals

- Basic statistics and linear algebra

- Introduction to machine learning concepts

- Simple classification and regression problems using Scikit-learn

Intermediate (3-9 months):

- Deeper understanding of algorithms

- Feature engineering techniques

- Model evaluation and selection

- Complete end-to-end projects

- Introduction to neural networks

Advanced (9+ months):

- Deep learning architectures

- Specialized topics (NLP, computer vision, reinforcement learning)

- Production deployment

- Research papers and state-of-the-art techniques

Essential Resources

Online Courses:

- Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning course (Coursera)

- Fast.ai’s Practical Deep Learning for Coders

- Google’s Machine Learning Crash Course

Books:

- “Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn and TensorFlow” by Aurélien Géron

- “Python Machine Learning” by Sebastian Raschka

- “The Hundred-Page Machine Learning Book” by Andriy Burkov

Communities:

- Kaggle forums and discussions

- Reddit communities (r/MachineLearning, r/learnmachinelearning)

- Stack Overflow for technical questions

- Local meetups and study groups

The key is consistent practice. Dedicate time regularly, work through examples, experiment with different approaches, and gradually tackle more complex problems.

The Ethics and Future of Machine Learning

As machine learning becomes more prevalent, ethical considerations become increasingly important.

Bias and Fairness

Machine learning models can perpetuate and amplify societal biases present in training data. Historical hiring data may reflect gender or racial discrimination, leading models trained on that data to discriminate similarly. Facial recognition systems perform worse on minorities when trained predominantly on majority populations.

Addressing bias requires:

- Careful dataset curation and auditing

- Diverse teams building ML systems

- Fairness-aware algorithms and evaluation

- Transparency about model limitations

- Regular auditing of deployed systems

Privacy and Security

Machine learning systems often require large amounts of personal data, raising privacy concerns. Techniques like differential privacy, federated learning, and privacy-preserving machine learning aim to enable learning while protecting individual privacy.

Security concerns include adversarial attacks, data poisoning (corrupting training data), and model theft (extracting trained models without authorization).

Transparency and Accountability

When machine learning systems make important decisions affecting people’s lives—loan approvals, hiring, medical diagnosis, criminal sentencing—we need transparency about how decisions are made and accountability when systems fail or cause harm.

Regulations like the EU’s AI Act and GDPR establish requirements for transparency and the right to explanation for automated decisions.

Job Displacement and Economic Impact

Automation powered by machine learning will displace some jobs while creating others. Society must grapple with this transition, potentially requiring:

- Education and retraining programs

- Social safety nets for displaced workers

- Policies to ensure broad benefit from automation

- New models of work and employment

The Path Forward

Machine learning will continue advancing rapidly. Future developments likely include:

- More efficient learning: Requiring less data and computation

- Better generalization: Models that adapt more readily to new situations

- Improved interpretability: Understanding and explaining model decisions

- Multimodal learning: Systems that integrate vision, language, and other modalities

- Neuromorphic computing: Hardware designed specifically for machine learning

- General AI: Systems approaching human-level versatility (though this remains distant)

As practitioners and users of machine learning, we share responsibility for ensuring these powerful technologies benefit humanity broadly while minimizing harms.

Conclusion: The Transformative Power of Learning Machines

Machine learning represents a fundamental shift in how we build intelligent systems. Rather than explicitly programming every rule and decision, we create systems that learn from experience—much as humans do. This enables solving complex problems that would be impractical or impossible with traditional programming approaches.

From recommending your next favorite song to diagnosing diseases, from autonomous vehicles navigating city streets to language models conversing naturally, machine learning is reshaping virtually every industry and aspect of modern life. The technology continues advancing rapidly, with new techniques, applications, and capabilities emerging constantly.

Yet machine learning isn’t magic. It’s a set of mathematical techniques for finding patterns in data. Success requires:

- Quality training data representative of the real world

- Appropriate algorithms and model architectures

- Careful evaluation and validation

- Domain expertise to guide development

- Ongoing monitoring and maintenance

- Ethical consideration of impacts

Whether you’re a business leader considering machine learning for your organization, a student contemplating a career in this field, or simply a curious individual wanting to understand the technology shaping our world, grasping the fundamentals of how machines learn is increasingly essential.

The journey from traditional programming to machine learning to deep learning and beyond represents humanity’s ongoing quest to create intelligent systems. As these technologies mature, they won’t replace human intelligence but rather augment it, handling routine tasks and complex pattern recognition while humans focus on creativity, strategy, empathy, and judgment.

Machine learning is not the future—it’s the present. Understanding how computers learn from data empowers you to participate in shaping how these technologies develop and are applied. Whether you become a practitioner building machine learning systems or an informed user benefiting from them, this knowledge opens doors to engaging with one of the most transformative technologies of our time.

The machines are learning. Now it’s our turn to learn about them, ensuring we guide this powerful technology toward outcomes that benefit all of humanity.