After building your first wheeled robot and experiencing both the satisfaction of smooth motion on flat surfaces and the frustration when small obstacles stop your robot completely, you begin recognizing that wheels have genuine limitations. A two-centimeter lip at a doorway becomes an insurmountable barrier. Loose gravel causes wheels to spin helplessly without traction. Steep ramps defeat even powerful motors as wheels slip rather than grip. These failure modes reveal that while wheels excel on prepared surfaces, they struggle when terrain becomes challenging. This recognition naturally leads to tracked robots, which use continuous belts or chains instead of discrete wheels to distribute robot weight over much longer contact areas with the ground. Tank treads, as these continuous tracks are commonly called, transform how robots interact with terrain by fundamentally changing the relationship between robot weight and ground contact.

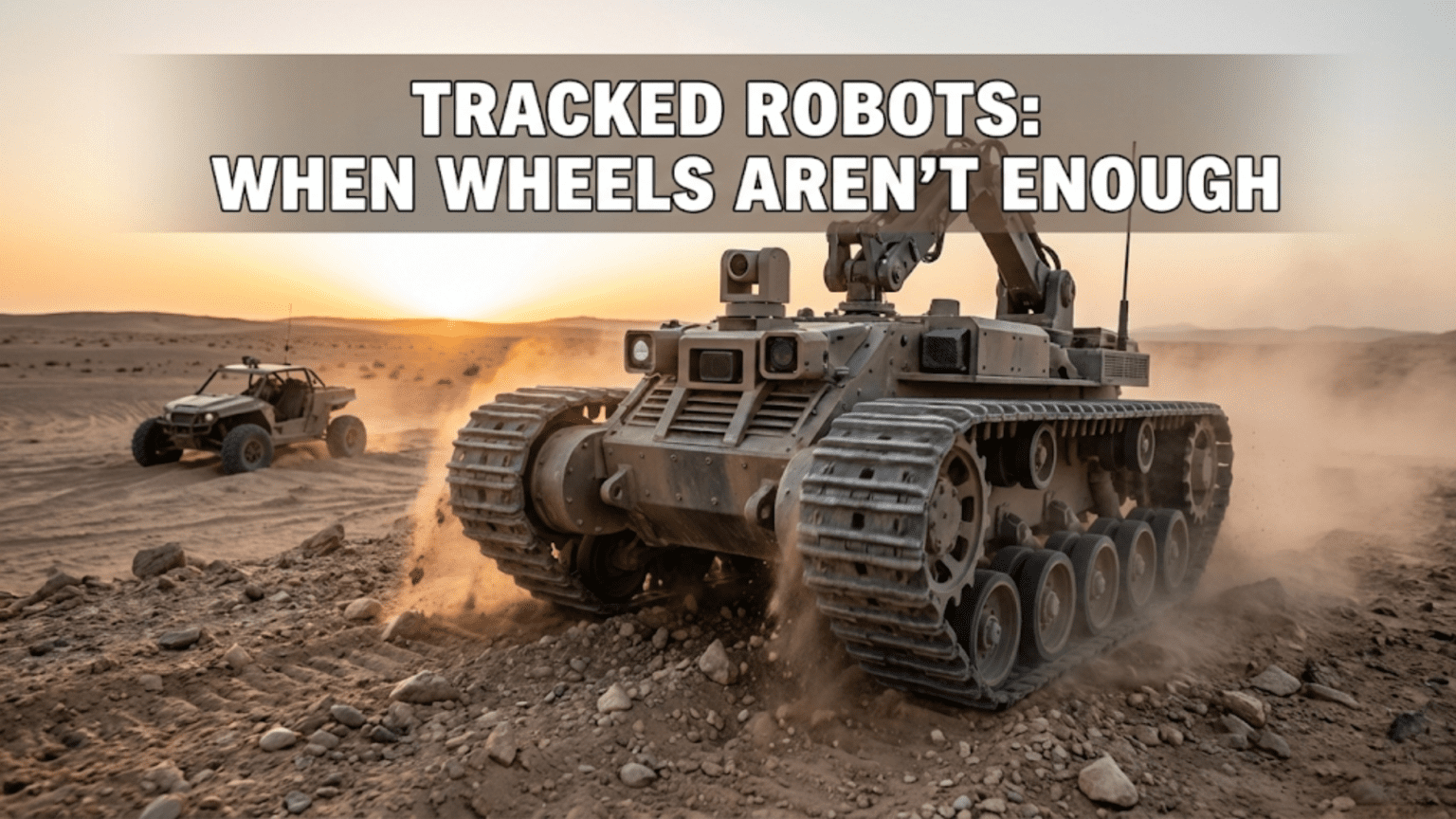

The visual similarity between robot tracks and those on military tanks or construction bulldozers immediately suggests ruggedness and capability in difficult conditions. This association proves largely accurate because tracks genuinely provide advantages over wheels for navigating obstacles, maintaining traction on loose surfaces, and operating in outdoor environments where terrain varies unpredictably. However, tracks introduce their own complexities, costs, and performance tradeoffs that make them inappropriate for many applications where wheels serve perfectly well. Understanding when tracks justify their additional complexity versus when wheels remain the better choice separates thoughtful engineering from simply choosing the most impressive-looking solution regardless of whether it fits actual requirements.

This article explores tracked robot design from fundamental principles through practical implementation. You will learn exactly what advantages tracks provide and what costs they impose, understand how tracked locomotion differs mechanically and mathematically from wheeled motion, discover the major track design variations and their respective strengths, and gain knowledge for deciding when your robot projects genuinely benefit from tracks versus when wheels remain the wiser choice. Rather than treating tracks as universally superior or dismissing them as unnecessarily complex, this balanced perspective helps you recognize the specific situations where tracks solve real problems that wheels cannot, enabling informed design decisions based on actual requirements rather than superficial impressions.

What Makes Tracks Different from Wheels

Before examining specific advantages and applications, understanding the fundamental mechanical and physical differences between tracks and wheels reveals why these differences create distinct performance characteristics across different terrains and tasks.

Tracks distribute robot weight over a long continuous contact patch rather than concentrating weight at small wheel contact points. A wheeled robot touches the ground only where its wheels contact the surface, creating high pressure at these small contact areas. A tracked robot contacts the ground continuously along the entire length of track touching the surface, spreading the same robot weight over a much larger area and therefore creating much lower ground pressure. This reduced pressure prevents the robot from sinking into soft surfaces like sand, mud, or snow that would swallow wheels. Thinking about walking across snow illustrates this principle clearly. With normal shoes, you sink deeply into soft snow because your weight concentrates at small footprint areas. Wearing snowshoes distributes your weight over larger areas, allowing you to walk on top of snow that would otherwise be impassable. Tracks provide this same weight distribution advantage for robots.

The continuous ground contact creates substantially more friction surface than discrete wheels provide. While wheels contact the ground at only a few small patches, tracks maintain contact across their entire length touching the ground. This extended contact means far more rubber or track material grips the terrain simultaneously, multiplying available traction. When wheels slip on loose gravel because their small contact patches cannot generate sufficient friction, tracks grip successfully because their large contact area provides far more total friction force. This traction advantage proves particularly valuable for climbing steep slopes where weight shifts rearward, further reducing friction available at individual wheels but barely affecting the long contact patch of tracks.

Obstacle crossing capability improves dramatically because tracks literally climb over obstacles rather than attempting to roll over them. When a wheeled robot encounters an obstacle higher than roughly one-third its wheel diameter, the wheel cannot generate sufficient force at the contact point to climb over the obstacle. The geometry works against the wheel, requiring more lifting force than the motor can provide through the wheel’s limited contact point. Tracks approach obstacles differently by conforming to obstacle shapes. The front of the track climbs onto the obstacle, then the continuous track pulls the rest of the robot up and over by distributing the climbing effort across the entire track length. Obstacles that stop wheeled robots completely often prove navigable for tracked robots of similar size and power.

The motion control mathematics actually simplifies compared to certain wheeled configurations because basic tracked robots use differential steering exactly like differential drive wheeled robots. Each track has its own drive motor. When both tracks move forward at equal speed, the robot drives straight. When one track moves faster than the other, the robot curves toward the slower track. When tracks move in opposite directions, the robot rotates in place. This control simplicity means the programming knowledge you developed for differential drive wheeled robots transfers directly to tracked robots without learning new control algorithms. The mechanical implementation differs significantly, but the high-level control logic remains identical.

However, tracks impose higher mechanical complexity than simple wheels on axles. A track system requires drive sprockets to power the track, idler wheels to route the track properly, return rollers to support the top of the track, and tensioning mechanisms to maintain proper track tension. These additional components increase part count, weight, and potential failure points compared to wheels bolted directly to motor shafts. Building a tracked robot from scratch demands more mechanical skill than building equivalent wheeled robots, though purchasing complete track assemblies mitigates this complexity by providing integrated systems ready to mount on your robot chassis.

The inevitable efficiency penalty from track friction creates shorter battery life for tracked robots compared to similar wheeled robots. Tracks continuously scrub against support rollers and the ground, generating friction that wheels minimize through their rolling motion. Additionally, turning tracked robots involves scrubbing the tracks sideways across the ground rather than simply rotating wheels in place, creating substantial resistance that drains batteries rapidly during frequent direction changes. This efficiency cost means tracked robots require larger batteries for equivalent runtime, or accept reduced operating duration compared to wheeled alternatives. You make this tradeoff when terrain challenges justify the performance advantages tracks provide.

Advantages Tracks Provide Over Wheels

Understanding the specific performance benefits that justify accepting track complexity and efficiency penalties helps you recognize when tracks genuinely solve problems rather than simply adding impressive appearance without functional advantage.

Soft terrain negotiation represents perhaps the most dramatic advantage tracks provide. On sand, mud, snow, or other surfaces that yield under pressure, wheeled robots sink until wheels bottom out or dig holes that trap them completely. The same robot on tracks typically traverses soft terrain successfully because its distributed weight creates pressure low enough to avoid sinking significantly. This capability extends the operational envelope from hard prepared surfaces to beaches, muddy fields, snowy ground, and other natural terrains completely inaccessible to wheeled robots. If your robot must operate outdoors in conditions where ground firmness varies or cannot be guaranteed, tracks provide capability that wheels cannot match regardless of motor power or wheel size.

Steep slope climbing capabilities exceed wheeled robots because tracks maintain traction even when weight shifts dramatically. On steep inclines, wheeled robots transfer weight to rear wheels while front wheels lose ground contact and traction. The reduced normal force on drive wheels limits available friction, causing wheels to slip before the robot reaches its theoretical maximum climbing angle. Tracked robots maintain long ground contact patches even on slopes, keeping substantial track area in firm contact despite weight transfer. This consistent contact maintains traction at angles where wheels would spin helplessly. Tracked robots routinely climb thirty to forty degree slopes that would defeat comparable wheeled designs.

Obstacle traversal allows tracked robots to cross barriers that stop wheeled robots completely. When a tracked robot encounters a rock, log, or step, the flexible track conforms to the obstacle shape. The front of the track climbs onto the obstacle, the continuous belt pulls the robot up, and the rear of the track eventually follows over. This climbing motion distributes the lifting effort across the entire track contact length rather than concentrating it at a single wheel contact point. The result lets tracked robots cross obstacles approaching half their track length in height, far exceeding the one-third wheel diameter limit typical of wheeled robots.

Trench and gap crossing becomes possible for tracked robots where wheels fall into gaps before bridging across. The long rigid track platform can span narrow gaps or trenches, keeping the robot supported even as the gap passes underneath between front and rear track contact areas. Wheeled robots with short wheelbases drop into gaps wider than their wheel spacing. This gap-crossing capability matters for outdoor robots navigating natural terrain with drainage ditches, gaps between rocks, or similar discontinuous surfaces.

Pushing and towing forces exceed wheeled robot capabilities because the large contact area prevents track slippage even under high longitudinal loads. When attempting to push obstacles or tow loads, wheeled robots quickly spin their wheels as the required force exceeds available traction. Tracked robots maintain grip through their extensive contact area, enabling them to exert substantially higher forces before slipping. This pushing capability makes tracked robots suitable for tasks like clearing debris or moving obstacles that wheeled robots cannot accomplish.

The intimidation factor, while not a rigorous engineering advantage, proves practically valuable for certain applications. Tracked robots visually communicate ruggedness and capability in ways wheeled robots do not. For competition robots, rescue robots, or other applications where visual presence matters, tracks provide psychological benefits beyond their functional advantages. This observation does not justify choosing tracks solely for appearance, but when tracks already suit your technical requirements, their impressive appearance provides bonus value.

Disadvantages and Limitations of Tracks

Balanced evaluation requires honestly assessing track limitations rather than viewing them as universally superior to wheels. Understanding what tracks sacrifice helps you make informed tradeoff decisions.

The efficiency penalty from continuous friction means tracked robots consume significantly more power than wheeled robots performing the same task. Every component the track touches creates friction. The drive sprocket, idler wheels, return rollers, and ground contact all generate resistance that motors must overcome. This cumulative friction typically results in tracked robots consuming twenty to forty percent more power than equivalent wheeled robots traveling the same distance at the same speed on hard surfaces. On the soft terrain where tracks excel, the efficiency gap narrows because wheels struggle inefficiently while tracks maintain better performance. However, on floors and pavement where most beginner robots operate, tracks waste substantial energy compared to wheels.

Turning resistance creates particularly dramatic power consumption when tracked robots rotate in place or execute tight turns. Unlike wheeled robots where wheels can rotate freely during turns, tracked robots must scrub their tracks sideways across the ground during all turns. Each turning maneuver literally drags the tracks perpendicular to their rolling direction, fighting friction across the entire ground contact area. This scrubbing consumes enormous energy, heats tracks and drive motors, and wears track surfaces rapidly. Robots that frequently change direction or operate in constrained spaces where tight maneuvering proves necessary suffer especially severe efficiency penalties from track turning resistance.

Mechanical complexity increases part count, assembly time, and maintenance requirements substantially. A simple wheeled robot might use two motors and four wheels, requiring minimal assembly beyond attaching wheels to motor shafts. An equivalent tracked robot requires motors, drive sprockets, drive chains or belts, track belts, multiple idler wheels, return rollers, tensioning mechanisms, and mounting hardware for all these components. Assembling this mechanical complexity demands more time and skill than simple wheel mounting. Additionally, tracks require periodic tension adjustment as belts stretch, occasional belt replacement as they wear, and regular inspection of all mechanical components for wear or damage. This ongoing maintenance burden exceeds the essentially zero maintenance typical of simple wheeled robots.

Surface damage potential increases because tracks can mark or damage certain floor surfaces. The continuous belt creates long scrub marks when turning on smooth floors. The treads molded into track surfaces can scratch or dent soft floor materials. Some track materials leave black marks on light-colored floors. If operating indoors on surfaces where appearance matters or damage carries consequences, tracks present risks that wheels with appropriate tire materials typically avoid. Outdoor robots obviously avoid this concern, but indoor tracked robots require consideration of floor compatibility before deploying them in environments where surface preservation matters.

Precision positioning challenges arise from track slippage and mechanical compliance making exact position control difficult. The flexible nature of tracks means they deform slightly under load, and they can slip unpredictably during turns. This compliance and slippage makes dead reckoning less accurate for tracked robots compared to wheeled robots with rigid wheels and encoders. Applications requiring precise positioning or accurate odometry may find tracks problematic despite their terrain advantages. Warehouse robots navigating to specific shelf positions, for example, typically use wheels rather than tracks because positioning accuracy matters more than terrain capability on smooth warehouse floors.

Speed limitations prevent tracked robots from matching the maximum speeds wheeled robots achieve on smooth surfaces. The friction from tracks limits practical top speed because excessive speed generates heat from friction faster than components can dissipate it. Track belts, drive motors, and sprockets all heat up during high-speed operation. Most tracked robots operate at speeds well below what equivalent motors could achieve with wheels. If your application values maximum speed on prepared surfaces, wheels significantly outperform tracks.

Cost increases stem from the greater parts count and mechanical complexity required for track systems. Complete track assemblies cost several times more than equivalent wheels and motor mounts. Building tracks from components yourself costs even more in parts and requires substantial mechanical fabrication capability. Only when track capabilities justify this cost premium do tracks make economic sense. Choosing tracks when wheels would suffice wastes money on unnecessary capability.

Track Design Variations and Configurations

Not all tracked robots use identical track implementations. Several design variations offer different tradeoffs appropriate for different requirements and constraints.

Simple belt tracks using continuous rubber or plastic belts resemble conveyor belts formed into endless loops. These belts run over drive sprockets and idler wheels, creating the simplest track implementation. Many small tracked robot kits use belt-style tracks because they prove relatively easy to manufacture and assemble. Belt tracks work adequately for lightweight robots on moderate terrain. However, they provide limited traction compared to more sophisticated designs, and the belts tend to stretch over time requiring frequent tension adjustment. The rubber or plastic belts also wear relatively quickly on abrasive surfaces. Despite these limitations, belt tracks remain popular for educational and hobby robots because of their simplicity and low cost.

Interlocking link tracks assemble from individual rigid segments connected by pins creating flexible chains. Each track segment typically has molded tread patterns providing traction. The interlocking links distribute loads across multiple connections rather than relying on belt strength, allowing link tracks to support heavier robots. Link tracks resist stretching better than belts, maintaining tension more consistently over time. The mechanical complexity increases substantially because link tracks require precise manufacturing of many identical segments and careful assembly to ensure smooth operation. Higher-end robot kits and custom-built tracked robots often use link tracks when durability and load capacity justify their additional complexity and cost.

Hybrid tracks combining rigid segments with flexible connections create variations attempting to capture advantages of both pure belts and pure link designs. Some designs use rigid plastic segments connected by flexible rubber sections. Others employ metal links with rubber pads for traction. These hybrid approaches balance the easy assembly and smooth operation of belts against the durability and load capacity of links. The optimal design varies based on specific application requirements including robot weight, terrain conditions, and acceptable cost.

Track width significantly affects performance with wider tracks distributing weight across greater area but creating higher turning resistance. Narrow tracks minimize turning resistance and robot width but concentrate weight into smaller contact areas. Matching track width to robot weight and terrain conditions optimizes performance. Lightweight robots benefit from narrower tracks reducing unnecessary turning resistance. Heavy robots or those operating on very soft terrain require wider tracks to achieve acceptable ground pressure. A rough guideline suggests track width of at least one-tenth the robot length for reasonable balance between weight distribution and maneuverability.

Track length directly determines obstacle-crossing height and gap-spanning capability. Longer tracks contact more ground area providing better weight distribution and traction. They also span larger gaps and climb higher obstacles through increased leverage from the longer moment arm between front and rear contact points. However, longer tracks increase robot size and weight. Very short tracks compromise terrain capability while minimizing size. Most tracked robots use tracks roughly equal in length to the overall robot chassis length, providing good terrain capability without excessive size.

The number of road wheels supporting the track along its length affects ride quality and ground pressure distribution. Single large road wheels create uneven pressure distribution with high peaks where wheels contact the track. Multiple small road wheels distribute pressure more evenly along the track length. Very heavy robots require many closely-spaced road wheels to prevent excessive track deflection between support points. Lighter robots work adequately with just a few road wheels. Balancing wheel count against mechanical complexity guides this design choice.

Suspension systems incorporated into track assemblies allow tracks to conform to irregular terrain while maintaining contact. Rigid track mounts work acceptably on moderate terrain but reduce contact and traction on very rough surfaces. Spring-suspended road wheels let tracks conform to terrain undulations, maintaining better contact and traction. Complex suspension systems with multiple articulated sections enable tracks to mold around large obstacles and navigate extremely rough terrain. However, suspension complexity adds substantial weight, cost, and mechanical difficulty. Only robots operating in severely challenging terrain justify elaborate track suspension systems.

Designing and Building Tracked Robots

If you have decided that tracks suit your robot requirements, practical design and implementation knowledge helps you create effective tracked robots rather than struggling with avoidable problems.

Start with purchased complete track assemblies for your first tracked robot rather than attempting to fabricate custom tracks from components. Many suppliers sell matched pairs of track assemblies designed for robotics including motors, drive sprockets, tracks, and mounting brackets. These integrated systems eliminate much of the mechanical complexity that makes custom track building challenging for beginners. Once you have experience with commercial track assemblies and understand how they function, designing custom tracks for specialized requirements becomes more approachable.

Select track assemblies appropriately sized for your robot’s intended weight and dimensions. Track specifications include load capacity indicating maximum weight they safely support. Choose tracks rated for at least twenty-five percent more than your expected robot weight, providing margin for payload additions and dynamic loads during climbing or turning. Track length should approximately match your planned chassis length. Track width should be at least one-tenth of track length for stability without excessive width.

Plan motor power requirements accounting for track friction and terrain challenges. Tracked robots require substantially more motor torque than equivalent wheeled robots because of track friction. Additionally, if you plan to climb obstacles or operate on difficult terrain, motors must provide torque overcoming both track friction and the additional resistance from terrain interaction. Estimate required motor power by doubling what you would specify for wheeled robots in similar applications, providing comfortable margin for track friction and terrain loads. Underpowered motors create frustratingly weak tracked robots that cannot climb obstacles or traverse terrain despite having tracks theoretically capable of these feats.

Design your chassis to maintain track tension while allowing reasonable track replacement or adjustment. Tracks that become too loose slip on drive sprockets, creating poor performance and accelerated wear. Tracks tensioned too tightly create excessive friction and rapid wear on all components. Ideal tension allows tracks to run smoothly without slipping while avoiding excessive tightness. Most track assemblies include tensioning mechanisms such as adjustable idler wheel positions or spring-loaded tensioners. Your chassis design should accommodate these adjustments and provide access for tension adjustment after assembly.

Consider track material appropriate for your operating environment. Rubber tracks provide good traction and quiet operation but wear quickly on abrasive surfaces. Harder plastic tracks last longer on rough terrain but provide reduced traction. Metal tracks offer maximum durability for extremely challenging conditions but create noise, require lubrication, and can damage surfaces. Indoor robots typically use rubber tracks balancing traction against floor protection. Outdoor robots might use harder materials accepting reduced traction for increased durability.

Plan electronics placement to protect components from track mechanisms. The close proximity of moving tracks, drive chains, and motors creates vibration and potential interference with sensitive electronics. Mount control electronics away from track mechanisms in well-secured enclosures. Use vibration isolation for precision sensors affected by mechanical vibration. Route wiring carefully to prevent entanglement with moving track components. The harsher mechanical environment around tracks demands more robust electronics mounting than simple wheeled robots require.

Implement emergency stops accessible during testing because tracked robots can exert substantial forces potentially causing injury or damage. Unlike light wheeled robots that present minimal hazard, tracked robots heavy enough to require tracks can push with significant force or continue moving despite encountering obstacles. Easily accessible physical emergency stop buttons or reliable wireless emergency stop capability allows immediately halting dangerous behavior during testing. Never operate tracked robots in areas with bystanders until thoroughly testing confirms safe behavior.

Test initially on varied terrain to understand your track’s capabilities and limitations. Wheeled robot testing occurs primarily on flat floors. Tracked robots deserve testing on the challenging terrain justifying their use. Set up test courses with obstacles, slopes, and varied surfaces representative of intended operating conditions. Observe how your robot handles different terrain types, noting which conditions work well versus which prove difficult. This testing reveals whether your track selection suits requirements or whether design modifications improve performance.

When to Choose Tracks Over Wheels

After understanding track advantages, disadvantages, and design considerations, making informed decisions about when tracks serve your robots better than wheels becomes possible through systematic evaluation of requirements.

Choose tracks when operating primarily on soft or loose terrain where wheels sink or lose traction. If your robot explores beaches, muddy fields, snowy areas, or other yielding surfaces, tracks provide essential capability that wheels cannot deliver regardless of motor power. The distributed weight and large contact area fundamentally solve the soft terrain problem that defeats wheeled robots. Any robot spending significant time on natural unprepared terrain benefits from tracks despite their efficiency and complexity costs.

Select tracks for applications requiring climbing substantial obstacles or steep slopes beyond wheeled robot capabilities. Warehouse robots on smooth floors do not need track obstacle-climbing capability. Search and rescue robots navigating disaster rubble absolutely require it. Evaluate your expected obstacles and terrain roughness honestly. If obstacles frequently exceed one-third wheel diameter or slopes approach thirty degrees, tracks prevent these challenges from stopping your robot. If your environment contains only modest obstacles and gentle slopes, wheels likely suffice.

Consider tracks for high-traction pushing or towing tasks where wheeled robots would spin their wheels. Applications involving clearing debris, pushing obstacles, or towing loads benefit from the superior traction tracks provide. Construction or utility robots moving objects around job sites work better with tracks. Delivery or navigation robots that never push anything do not gain value from track traction advantages.

Avoid tracks for precision positioning applications on smooth surfaces where wheels provide better odometry and efficiency. Factory automation, warehouse navigation, and indoor delivery robots operating on floors benefit from wheeled designs. The complexity and slippage inherent in tracks undermines positioning accuracy while providing no terrain capability benefits on smooth prepared surfaces. Choose wheels for these applications, reserving tracks for genuinely challenging terrain.

Skip tracks for maximum speed applications where efficiency and low rolling resistance matter more than terrain capability. Racing robots, outdoor patrol robots covering long distances on roads, or any application prioritizing speed over terrain capability should use wheels. Tracks simply cannot match wheeled robot speeds on smooth surfaces because friction limits practical top speed even with powerful motors.

Budget carefully for tracks accepting that they cost substantially more than wheels for similar robot size. If your project budget constrains spending and your terrain does not absolutely require tracks, choosing wheels reduces costs. Only invest in tracks when they solve real problems wheels cannot handle. Spending track money without gaining corresponding capability wastes resources better allocated elsewhere in your robot design.

Conclusion: Tracks as Specialized Tools

Tracked robots occupy an important niche in mobile robotics, providing essential capabilities for challenging terrain and obstacle-rich environments. However, they remain specialized tools appropriate for specific applications rather than universally superior alternatives to wheels. The mechanical complexity, efficiency penalty, and cost premium tracks impose demand justification through genuine performance requirements that wheels cannot meet. When terrain challenges justify these costs, tracks transform impossible tasks into achievable missions. When operating on smooth prepared surfaces, tracks waste money and energy providing capabilities you never use.

Your progression through robotics will likely begin with wheeled robots because most learning occurs on flat floors where wheels excel. This wheeled foundation proves valuable even if you eventually work with tracked robots because the control principles transfer directly while wheels teach fundamental concepts without track complexity complications. After mastering wheeled robotics and attempting to deploy wheeled robots in challenging environments, you will recognize exactly when tracks solve real problems rather than viewing them as abstract alternatives to wheels.

The decision between wheels and tracks ultimately reduces to honest assessment of your operating environment and requirements. Smooth floors strongly favor wheels. Rocky outdoor terrain strongly favors tracks. Many applications fall between these extremes, requiring careful evaluation of terrain roughness, obstacle frequency, required precision, acceptable cost, and efficiency demands. Neither wheels nor tracks universally dominates, making context and specific requirements the determining factors in optimal design choices.

When you do build your first tracked robot, apply the lessons learned from wheeled robots while respecting the additional complexity tracks introduce. Start with commercial track assemblies before attempting custom designs. Size motors generously accounting for track friction. Test thoroughly on representative terrain. Maintain tracks properly through tension adjustment and wear monitoring. These practices, combined with fundamental mobile robotics knowledge from wheeled robots, enable creating effective tracked robots that actually deliver the terrain capability and obstacle-crossing performance that justify their additional cost and complexity.