Constructors initialize objects when they are created, but what happens when objects are destroyed? If your object allocated memory with new, opened files, established network connections, or acquired other resources, those resources need to be released when the object is no longer needed. Forgetting to clean up resources causes memory leaks, file handle exhaustion, and other resource management problems that accumulate over time until your program or system fails. Destructors solve this problem by providing special member functions that run automatically when objects are destroyed, ensuring that cleanup happens consistently and completely without requiring programmers to remember manual cleanup steps every time they use an object.

Think of destructors like the automatic shutdown sequence that runs when you power off your computer. You do not manually close every open file, disconnect every network connection, and release every allocated resource. Instead, the operating system runs a systematic shutdown procedure that ensures everything is properly closed, saved, and released before powering down. Destructors work the same way for objects. When an object goes out of scope or is explicitly deleted, the destructor runs automatically, performing all necessary cleanup operations to release resources and leave the system in a clean state. This automatic cleanup guarantees that resources are always released, even if exceptions are thrown or functions return early from multiple exit points.

The power of destructors comes from their integration with C++’s scope and lifetime rules, creating what programmers call RAII, which stands for Resource Acquisition Is Initialization. This powerful idiom means that you acquire resources in constructors and release them in destructors, tying resource lifetime to object lifetime. When an object is created, its constructor acquires needed resources. When the object is destroyed, whether through normal scope exit, exception unwinding, or explicit deletion, the destructor automatically releases those resources. This automatic management eliminates entire categories of resource leaks and makes exception-safe code natural to write. Understanding destructors and RAII transforms how you think about resource management, moving from manual tracking and cleanup to automatic, guaranteed cleanup through object lifetime.

Let me start by showing you the basic syntax of destructors and how they pair with constructors to manage resources:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class SimpleResource {

private:

std::string name;

int* data;

public:

// Constructor - acquires resources

SimpleResource(const std::string& resourceName) : name(resourceName) {

data = new int[100]; // Allocate memory

std::cout << "Constructor: " << name << " - memory allocated" << std::endl;

}

// Destructor - releases resources

~SimpleResource() {

delete[] data; // Free memory

std::cout << "Destructor: " << name << " - memory freed" << std::endl;

}

void use() {

std::cout << "Using resource: " << name << std::endl;

}

};

void demonstrateAutomaticCleanup() {

std::cout << "=== Entering function ===" << std::endl;

SimpleResource resource1("Resource A");

resource1.use();

{

SimpleResource resource2("Resource B");

resource2.use();

std::cout << "Exiting inner scope..." << std::endl;

} // resource2 destructor called automatically here

std::cout << "Back in outer scope" << std::endl;

resource1.use();

std::cout << "Exiting function..." << std::endl;

} // resource1 destructor called automatically here

int main() {

demonstrateAutomaticCleanup();

std::cout << "\n=== Back in main ===" << std::endl;

return 0;

}The destructor has the same name as the class but with a tilde prefix, takes no parameters, and has no return type. When resource two goes out of scope at the closing brace of the inner block, its destructor runs automatically, freeing the allocated memory. When the function ends and resource one goes out of scope, its destructor runs automatically. This automatic cleanup means you cannot forget to free memory because the cleanup is tied to scope rules that the compiler enforces. The pairing of resource acquisition in the constructor with resource release in the destructor creates a powerful pattern where resource lifetime matches object lifetime exactly.

Destructors run in reverse order of construction, which ensures proper cleanup when objects depend on each other:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Component {

private:

std::string name;

public:

Component(const std::string& n) : name(n) {

std::cout << " Component constructed: " << name << std::endl;

}

~Component() {

std::cout << " Component destroyed: " << name << std::endl;

}

void display() const {

std::cout << " Component: " << name << std::endl;

}

};

class System {

private:

std::string systemName;

Component component1;

Component component2;

Component component3;

public:

System(const std::string& name)

: systemName(name),

component1("Component A"),

component2("Component B"),

component3("Component C")

{

std::cout << "System constructed: " << systemName << std::endl;

}

~System() {

std::cout << "System destroyed: " << systemName << std::endl;

}

void showComponents() const {

std::cout << "\nSystem: " << systemName << std::endl;

component1.display();

component2.display();

component3.display();

}

};

int main() {

std::cout << "=== Creating System ===" << std::endl;

System mySystem("Production System");

mySystem.showComponents();

std::cout << "\n=== Program ending ===" << std::endl;

return 0;

}When the System object is created, its member components are constructed first in the order they appear in the class definition, then the System constructor body runs. When the System is destroyed, the opposite order occurs. The System destructor runs first, then the component destructors run in reverse order of construction, ensuring that component three is destroyed before component two, which is destroyed before component one. This ordering ensures that if one component depends on another, the dependent component is destroyed before the component it depends on, preventing use-after-destruction errors.

The RAII pattern leverages destructors to guarantee resource cleanup even when exceptions occur:

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

#include <string>

#include <stdexcept>

class FileHandler {

private:

std::string filename;

std::ofstream file;

public:

// Constructor opens file

FileHandler(const std::string& name) : filename(name) {

file.open(filename);

if (!file.is_open()) {

throw std::runtime_error("Failed to open file: " + filename);

}

std::cout << "File opened: " << filename << std::endl;

}

// Destructor ensures file is closed

~FileHandler() {

if (file.is_open()) {

file.close();

std::cout << "File closed: " << filename << std::endl;

}

}

void write(const std::string& data) {

if (!file.is_open()) {

throw std::runtime_error("File not open");

}

file << data << std::endl;

std::cout << "Wrote to file: " << data << std::endl;

}

};

void processWithException() {

std::cout << "\n=== Function with exception ===" << std::endl;

FileHandler handler("output.txt");

handler.write("First line");

handler.write("Second line");

// Simulate an error

throw std::runtime_error("Processing error occurred");

// This line never executes

handler.write("This line never gets written");

}

void processNormally() {

std::cout << "\n=== Function without exception ===" << std::endl;

FileHandler handler("normal.txt");

handler.write("Line 1");

handler.write("Line 2");

handler.write("Line 3");

std::cout << "Processing completed normally" << std::endl;

}

int main() {

// Normal case - file closed automatically at end of scope

try {

processNormally();

} catch (const std::exception& e) {

std::cout << "Caught exception: " << e.what() << std::endl;

}

// Exception case - file still closed automatically during stack unwinding

try {

processWithException();

} catch (const std::exception& e) {

std::cout << "Caught exception: " << e.what() << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}The FileHandler destructor ensures the file is closed regardless of how the function exits. When the exception is thrown in process with exception, the stack unwinds and the FileHandler destructor runs automatically, closing the file before the exception propagates. This automatic cleanup during exception unwinding is what makes RAII so powerful. You write cleanup code once in the destructor, and it runs correctly whether the function returns normally, returns early from multiple exit points, or exits via exception. Without RAII, you would need to manually close the file before every return and catch exceptions just to clean up, leading to complex error-prone code with duplicated cleanup logic.

Let me show you a comprehensive example demonstrating destructors managing multiple types of resources in a realistic application:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <memory>

class DatabaseConnection {

private:

std::string connectionString;

bool isConnected;

public:

DatabaseConnection(const std::string& connStr)

: connectionString(connStr), isConnected(false)

{

// Simulate establishing connection

std::cout << " Connecting to database: " << connectionString << std::endl;

isConnected = true;

std::cout << " Database connected" << std::endl;

}

~DatabaseConnection() {

disconnect();

}

void disconnect() {

if (isConnected) {

std::cout << " Disconnecting from database: " << connectionString << std::endl;

isConnected = false;

}

}

void executeQuery(const std::string& query) {

if (!isConnected) {

throw std::runtime_error("Not connected to database");

}

std::cout << " Executing query: " << query << std::endl;

}

bool connected() const { return isConnected; }

};

class NetworkSocket {

private:

std::string address;

int port;

bool isOpen;

public:

NetworkSocket(const std::string& addr, int p)

: address(addr), port(p), isOpen(false)

{

std::cout << " Opening socket to " << address << ":" << port << std::endl;

isOpen = true;

std::cout << " Socket opened" << std::endl;

}

~NetworkSocket() {

close();

}

void close() {

if (isOpen) {

std::cout << " Closing socket to " << address << ":" << port << std::endl;

isOpen = false;

}

}

void send(const std::string& data) {

if (!isOpen) {

throw std::runtime_error("Socket not open");

}

std::cout << " Sending data: " << data << std::endl;

}

};

class MemoryBuffer {

private:

std::string bufferName;

int* buffer;

size_t size;

public:

MemoryBuffer(const std::string& name, size_t bufferSize)

: bufferName(name), size(bufferSize)

{

std::cout << " Allocating buffer: " << bufferName

<< " (" << size << " elements)" << std::endl;

buffer = new int[size];

std::cout << " Buffer allocated" << std::endl;

}

~MemoryBuffer() {

std::cout << " Deallocating buffer: " << bufferName << std::endl;

delete[] buffer;

std::cout << " Buffer deallocated" << std::endl;

}

void fill(int value) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < size; i++) {

buffer[i] = value;

}

std::cout << " Buffer filled with value: " << value << std::endl;

}

int* getData() { return buffer; }

size_t getSize() const { return size; }

};

class ApplicationServer {

private:

std::string serverName;

DatabaseConnection database;

NetworkSocket socket;

MemoryBuffer cache;

public:

ApplicationServer(const std::string& name)

: serverName(name),

data.base("server=localhost;db=myapp"), //remove .

socket("192.168.1.100", 8080),

cache("ServerCache", 1000)

{

std::cout << "\nApplication Server constructed: " << serverName << std::endl;

}

~ApplicationServer() {

std::cout << "\nApplication Server destroyed: " << serverName << std::endl;

}

void processRequest(const std::string& request) {

std::cout << "\n=== Processing Request ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Request: " << request << std::endl;

cache.fill(0);

database.executeQuery("SELECT * FROM users");

socket.send("Response data");

std::cout << "Request processed successfully" << std::endl;

}

void displayStatus() const {

std::cout << "\n=== Server Status ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Server: " << serverName << std::endl;

std::cout << "Database: " << (database.connected() ? "Connected" : "Disconnected") << std::endl;

std::cout << "Cache size: " << cache.getSize() << " elements" << std::endl;

}

};

void demonstrateNormalOperation() {

std::cout << "\n=== Normal Operation ===" << std::endl;

ApplicationServer server("ProductionServer");

server.displayStatus();

server.processRequest("GET /api/users");

std::cout << "\n=== Exiting normal operation ===" << std::endl;

}

void demonstrateExceptionHandling() {

std::cout << "\n=== Operation with Exception ===" << std::endl;

try {

ApplicationServer server("TestServer");

server.displayStatus();

server.processRequest("GET /api/data");

// Simulate unexpected error

throw std::runtime_error("Unexpected server error");

// This line never executes

server.processRequest("This request never happens");

} catch (const std::exception& e) {

std::cout << "\nCaught exception: " << e.what() << std::endl;

}

std::cout << "\n=== Exception handled, resources cleaned up ===" << std::endl;

}

int main() {

demonstrateNormalOperation();

std::cout << "\n" << std::string(60, '=') << "\n" << std::endl;

demonstrateExceptionHandling();

return 0;

}This comprehensive example shows destructors managing multiple resource types simultaneously. The ApplicationServer contains a database connection, network socket, and memory buffer, each with its own destructor. When the ApplicationServer is destroyed, whether normally or via exception, its destructor runs first, then the member destructors run in reverse order of construction. The database disconnects, the socket closes, and the memory buffer is deallocated automatically. This cascade of cleanup happens correctly in all scenarios without manual intervention, demonstrating RAII working across multiple resource types and layers of abstraction.

Virtual destructors become essential when working with inheritance and polymorphism, where you delete objects through base class pointers:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

// Base class WITHOUT virtual destructor - demonstrates the problem

class ShapeNonVirtual {

protected:

std::string name;

public:

ShapeNonVirtual(const std::string& n) : name(n) {

std::cout << "Shape constructed: " << name << std::endl;

}

// Non-virtual destructor - DANGEROUS with inheritance!

~ShapeNonVirtual() {

std::cout << "Shape destroyed: " << name << std::endl;

}

};

class CircleNonVirtual : public ShapeNonVirtual {

private:

double* radiusData; // Dynamically allocated

public:

CircleNonVirtual(const std::string& n, double r)

: ShapeNonVirtual(n)

{

radiusData = new double(r);

std::cout << "Circle constructed with radius data" << std::endl;

}

~CircleNonVirtual() {

std::cout << "Circle destructor - freeing radius data" << std::endl;

delete radiusData;

}

};

// Base class WITH virtual destructor - correct approach

class Shape {

protected:

std::string name;

public:

Shape(const std::string& n) : name(n) {

std::cout << "Shape constructed: " << name << std::endl;

}

// Virtual destructor - enables proper cleanup through base pointer

virtual ~Shape() {

std::cout << "Shape destroyed: " << name << std::endl;

}

virtual void draw() const {

std::cout << "Drawing shape: " << name << std::endl;

}

};

class Circle : public Shape {

private:

double* radiusData;

public:

Circle(const std::string& n, double r)

: Shape(n)

{

radiusData = new double(r);

std::cout << "Circle constructed with radius data" << std::endl;

}

~Circle() {

std::cout << "Circle destructor - freeing radius data" << std::endl;

delete radiusData;

}

void draw() const override {

std::cout << "Drawing circle: " << name << std::endl;

}

};

class Rectangle : public Shape {

private:

double* dimensionData;

public:

Rectangle(const std::string& n)

: Shape(n)

{

dimensionData = new double[2];

std::cout << "Rectangle constructed with dimension data" << std::endl;

}

~Rectangle() {

std::cout << "Rectangle destructor - freeing dimension data" << std::endl;

delete[] dimensionData;

}

void draw() const override {

std::cout << "Drawing rectangle: " << name << std::endl;

}

};

void demonstrateNonVirtualDestructor() {

std::cout << "=== Non-Virtual Destructor Problem ===" << std::endl;

ShapeNonVirtual* shape = new CircleNonVirtual("Circle1", 5.0);

delete shape; // Only base destructor called - MEMORY LEAK!

// Circle destructor never runs, radiusData never freed

std::cout << std::endl;

}

void demonstrateVirtualDestructor() {

std::cout << "=== Virtual Destructor Solution ===" << std::endl;

Shape* circle = new Circle("Circle2", 10.0);

Shape* rect = new Rectangle("Rect1");

circle->draw();

rect->draw();

std::cout << "\nDeleting through base pointers:" << std::endl;

delete circle; // Both Circle and Shape destructors called

std::cout << std::endl;

delete rect; // Both Rectangle and Shape destructors called

std::cout << std::endl;

}

void demonstratePolymorphicCollection() {

std::cout << "=== Polymorphic Collection ===" << std::endl;

std::vector<Shape*> shapes;

shapes.push_back(new Circle("Circle3", 3.0));

shapes.push_back(new Rectangle("Rect2"));

shapes.push_back(new Circle("Circle4", 7.0));

std::cout << "\nDrawing all shapes:" << std::endl;

for (const auto& shape : shapes) {

shape->draw();

}

std::cout << "\nCleaning up collection:" << std::endl;

for (auto& shape : shapes) {

delete shape; // Virtual destructor ensures proper cleanup

}

shapes.clear();

std::cout << std::endl;

}

int main() {

demonstrateNonVirtualDestructor();

demonstrateVirtualDestructor();

demonstratePolymorphicCollection();

return 0;

}When you delete an object through a base class pointer and the base class destructor is not virtual, only the base class destructor runs, never calling the derived class destructor. This causes resource leaks because any resources allocated in the derived class are never freed. Making the base class destructor virtual solves this problem by enabling the correct destructor to run based on the actual object type, ensuring that derived class destructors run before the base class destructor. The rule is simple: if a class has any virtual functions or is intended as a base class, always make its destructor virtual. This prevents resource leaks when objects are deleted through base class pointers.

Understanding when destructors run helps you reason about resource lifetime and avoid common mistakes:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

class Resource {

private:

int id;

public:

Resource(int identifier) : id(identifier) {

std::cout << "Resource " << id << " constructed" << std::endl;

}

~Resource() {

std::cout << "Resource " << id << " destroyed" << std::endl;

}

Resource(const Resource& other) : id(other.id) {

std::cout << "Resource " << id << " copied" << std::endl;

}

void use() {

std::cout << "Using resource " << id << std::endl;

}

};

void demonstrateLifetime() {

std::cout << "=== Function Scope ===" << std::endl;

Resource r1(1);

r1.use();

std::cout << "End of function" << std::endl;

}

void demonstrateBlockScope() {

std::cout << "\n=== Block Scope ===" << std::endl;

Resource r1(2);

{

Resource r2(3);

r1.use();

r2.use();

std::cout << "End of inner block" << std::endl;

} // r2 destroyed here

r1.use();

std::cout << "End of function" << std::endl;

} // r1 destroyed here

void demonstrateTemporary() {

std::cout << "\n=== Temporary Objects ===" << std::endl;

Resource(4).use(); // Temporary created and destroyed immediately after use

std::cout << "After temporary" << std::endl;

}

void demonstrateDynamic() {

std::cout << "\n=== Dynamic Allocation ===" << std::endl;

Resource* r1 = new Resource(5);

r1->use();

std::cout << "Before manual delete" << std::endl;

delete r1; // Explicit deletion required - destructor called

std::cout << "After manual delete" << std::endl;

}

int main() {

demonstrateLifetime();

demonstrateBlockScope();

demonstrateTemporary();

demonstrateDynamic();

std::cout << "\n=== Exiting main ===" << std::endl;

return 0;

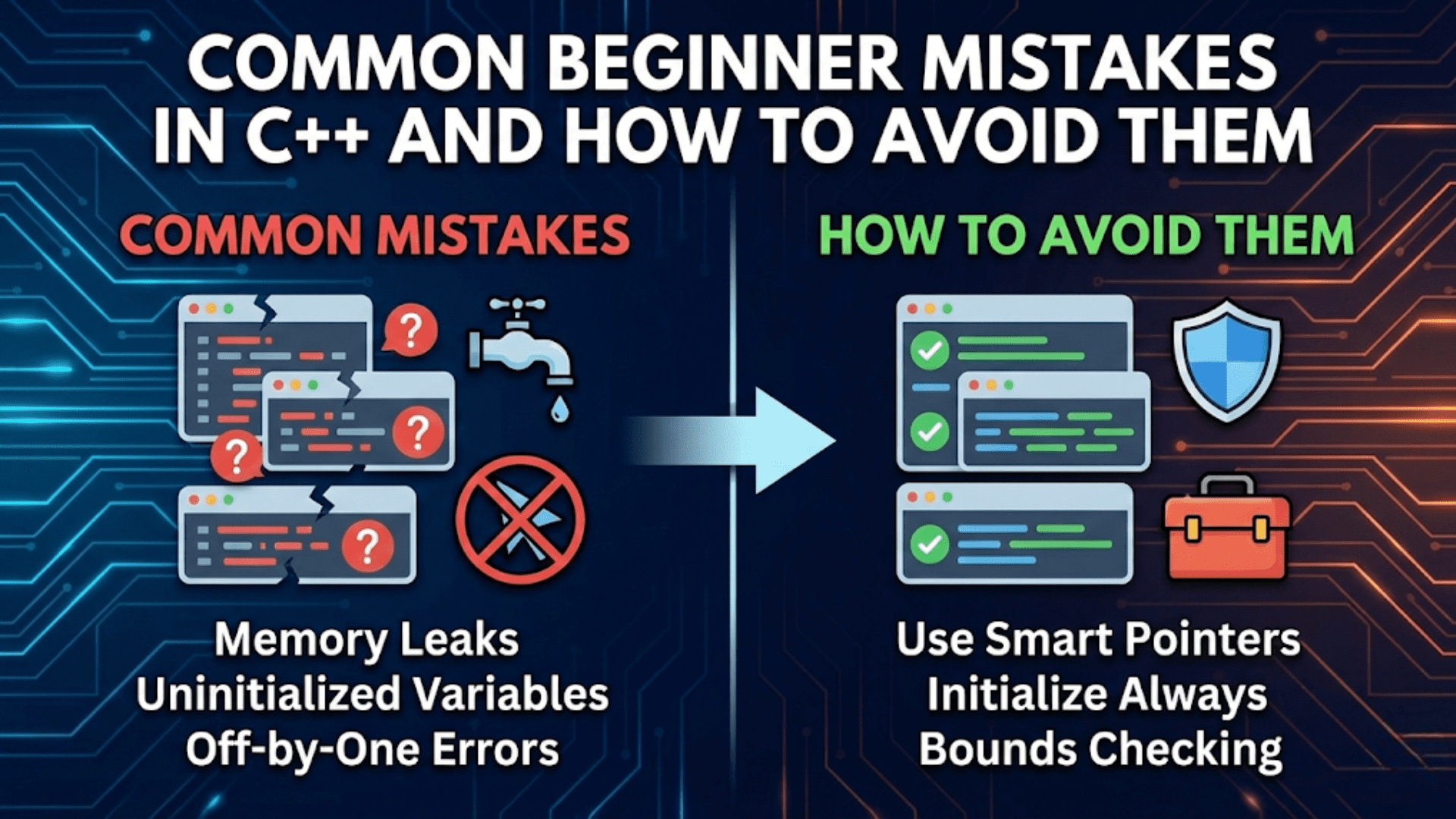

}Stack-allocated objects are destroyed automatically when they go out of scope, following the Last In First Out principle. Temporary objects are destroyed at the end of the full expression that creates them. Dynamically allocated objects with new are never destroyed automatically and must be explicitly deleted, which is why smart pointers that automate deletion through destructors are strongly preferred. Understanding these lifetime rules helps you predict when destructors run and design classes that manage resources correctly.

Destructors should not throw exceptions because they often run during stack unwinding when another exception is already active, and having two active exceptions simultaneously terminates the program:

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

class BadDestructor {

public:

~BadDestructor() noexcept(false) { // Dangerous! Can throw

throw std::runtime_error("Destructor threw exception");

}

};

class GoodDestructor {

public:

~GoodDestructor() noexcept { // Marked noexcept - good practice

try {

// Cleanup code that might fail

// Handle errors internally rather than throwing

} catch (...) {

// Log error but do not re-throw

std::cerr << "Error during cleanup, handled internally" << std::endl;

}

}

};

int main() {

try {

GoodDestructor good;

std::cout << "Good destructor example completed" << std::endl;

} catch (...) {

std::cout << "Exception caught" << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}Mark destructors noexcept to document that they will not throw exceptions. If cleanup operations might fail, catch exceptions internally and handle errors through logging or other mechanisms rather than propagating exceptions out of the destructor. This discipline prevents program termination from destructor exceptions during exception unwinding.

Key Takeaways

Destructors are special member functions that run automatically when objects are destroyed, ensuring cleanup happens consistently without manual intervention. Destructors have the same name as the class with a tilde prefix, take no parameters, have no return type, and run automatically when objects go out of scope, are explicitly deleted, or when stack unwinding occurs during exception handling. The automatic nature of destructors makes forgetting cleanup impossible when resources are managed through RAII.

The RAII pattern ties resource lifetime to object lifetime by acquiring resources in constructors and releasing them in destructors, creating automatic resource management that works correctly with exceptions and multiple exit points. Destructors run in reverse order of construction, ensuring proper cleanup when objects contain other objects or derive from base classes. This ordering guarantees that dependent objects are destroyed before the objects they depend on.

Virtual destructors are essential for base classes in inheritance hierarchies because they ensure derived class destructors run when objects are deleted through base class pointers, preventing resource leaks. Always make destructors virtual if a class has any virtual functions or serves as a base class. Destructors should be marked noexcept and should not throw exceptions because throwing from destructors during stack unwinding terminates the program. Understanding destructors deeply enables creating classes that manage resources automatically and safely through RAII, eliminating resource leaks while making exception-safe code natural to write.