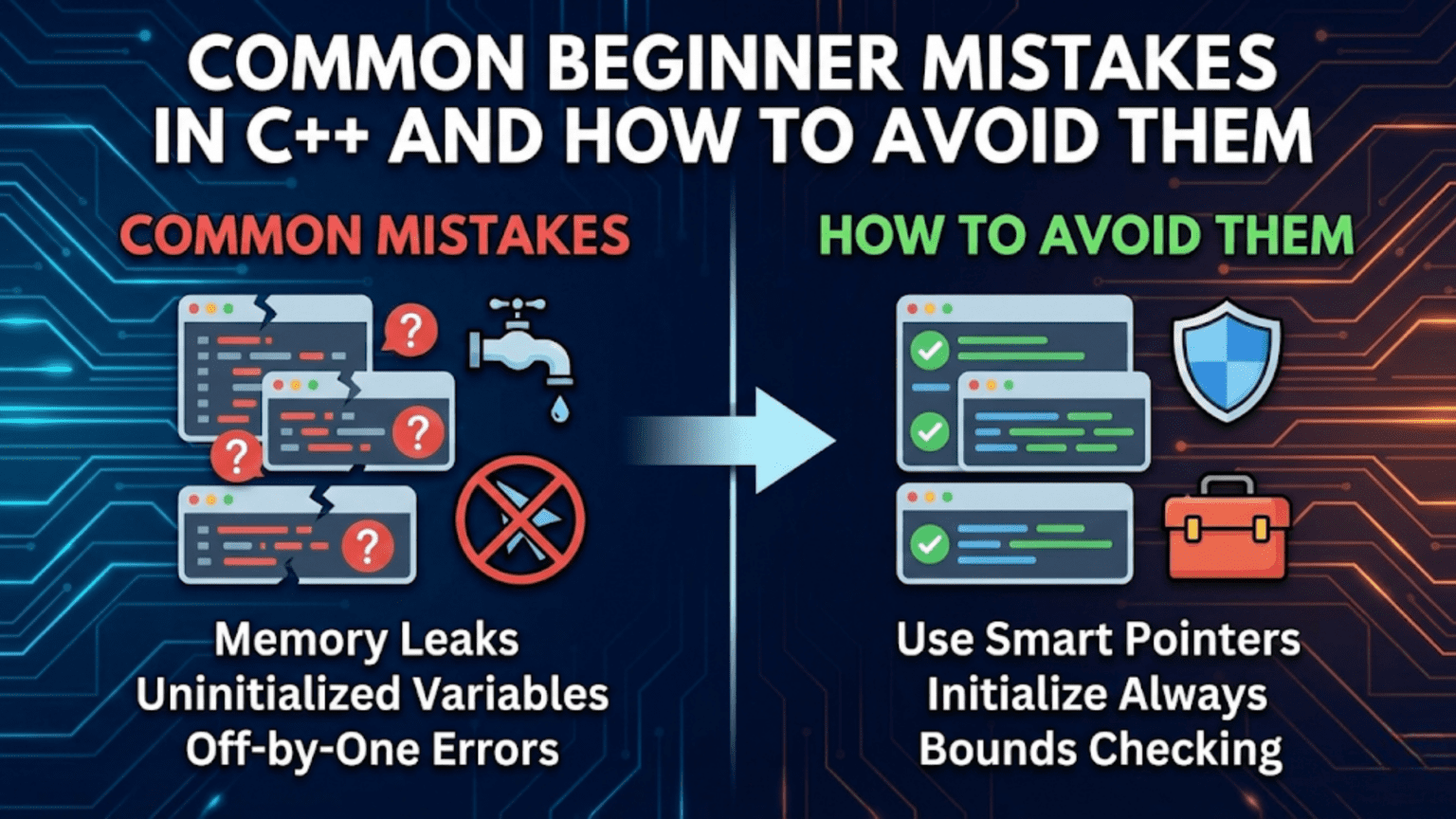

Learning C++ means making mistakes—it’s an inevitable and valuable part of the learning process. But some mistakes appear so frequently among beginners that recognizing them early can save countless hours of debugging frustration. These common errors range from simple oversights like forgetting semicolons to subtle bugs like uninitialized variables that cause unpredictable behavior. Understanding these pitfalls before they bite you transforms learning from a process of painful trial and error to one of informed progress where you avoid known traps while focusing on genuinely new challenges. Each mistake represents a lesson that thousands of programmers learned the hard way, and you can benefit from their collective experience.

Think of common beginner mistakes like traffic signs warning of hazards ahead. When you see a “slippery when wet” sign, you slow down and drive more carefully because someone learned through experience that this section of road becomes dangerous in rain. Programming mistakes work similarly—experienced programmers recognize patterns of errors they’ve seen repeatedly and can warn newcomers about them. Some mistakes cause immediate compilation errors that are easy to fix. Others compile successfully but produce wrong results or crash at runtime, making them harder to track down. The most insidious bugs compile and run without obvious problems but cause subtle incorrect behavior that only manifests in specific situations.

The power of learning common mistakes comes from developing pattern recognition that helps you write correct code the first time and debug problems more efficiently when they occur. When your program crashes with a segmentation fault, knowing that this typically indicates dereferencing a null or invalid pointer narrows your search immediately. When calculations produce wrong results, knowing to check for integer division or uninitialized variables guides your investigation. Understanding common mistakes transforms you from someone who debugs through random changes hoping something works to someone who systematically identifies and fixes issues based on recognizable patterns.

Let me start with one of the most fundamental mistakes—forgetting to initialize variables before using them:

#include <iostream>

void demonstrateUninitializedVariables() {

// MISTAKE: Uninitialized variable

int count; // Contains garbage value

std::cout << "Count (uninitialized): " << count << std::endl; // Unpredictable output

// CORRECT: Initialize variables when declaring them

int properCount = 0;

std::cout << "Count (initialized): " << properCount << std::endl;

// MISTAKE: Using variable before initialization

double price;

double total = price * 2; // price has garbage value

std::cout << "Total (bad): " << total << std::endl;

// CORRECT: Initialize before use

double properPrice = 19.99;

double properTotal = properPrice * 2;

std::cout << "Total (good): " << properTotal << std::endl;

}

void demonstrateArrayInitialization() {

// MISTAKE: Uninitialized array

int numbers[5]; // Contains garbage values

std::cout << "Uninitialized array: ";

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

std::cout << numbers[i] << " "; // Unpredictable values

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// CORRECT: Initialize array

int properNumbers[5] = {0}; // All elements set to 0

std::cout << "Initialized array: ";

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

std::cout << properNumbers[i] << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// CORRECT: Explicit initialization

int specificNumbers[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

std::cout << "Explicitly initialized: ";

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

std::cout << specificNumbers[i] << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

}

int main() {

demonstrateUninitializedVariables();

std::cout << std::endl;

demonstrateArrayInitialization();

return 0;

}Uninitialized variables contain whatever random values happened to be in that memory location, leading to unpredictable behavior that changes between program runs or even within the same run. This mistake is particularly insidious because programs often appear to work during testing when the garbage values happen to be reasonable, then fail mysteriously in production when different garbage values cause problems. Always initialize variables when you declare them, using explicit values or default initialization syntax. This single practice eliminates an entire category of bugs.

Array bounds violations represent another extremely common and dangerous mistake:

#include <iostream>

void demonstrateArrayBounds() {

int numbers[5] = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

// MISTAKE: Accessing beyond array bounds

std::cout << "Valid access: numbers[4] = " << numbers[4] << std::endl;

std::cout << "Invalid access: numbers[5] = " << numbers[5] << std::endl; // Undefined behavior!

std::cout << "Invalid access: numbers[10] = " << numbers[10] << std::endl; // Very bad!

// MISTAKE: Off-by-one error in loop

std::cout << "Loop with off-by-one error: ";

for (int i = 0; i <= 5; i++) { // Should be i < 5

std::cout << numbers[i] << " "; // Accesses invalid index 5

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// CORRECT: Proper loop bounds

std::cout << "Correct loop: ";

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

std::cout << numbers[i] << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// MISTAKE: Writing beyond array bounds

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) { // Array only has 5 elements!

numbers[i] = i * 10; // Corrupts memory beyond array

}

}

void demonstrateStringBounds() {

std::string text = "Hello";

// MISTAKE: Accessing beyond string length

std::cout << "String length: " << text.length() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Valid: text[0] = " << text[0] << std::endl;

// std::cout << "Invalid: text[10] = " << text[10] << std::endl; // Undefined behavior

// CORRECT: Check bounds or use at() which throws exception

try {

std::cout << "Using at(10): " << text.at(10) << std::endl;

} catch (const std::out_of_range& e) {

std::cout << "Caught exception: " << e.what() << std::endl;

}

}

int main() {

demonstrateArrayBounds();

std::cout << std::endl;

demonstrateStringBounds();

return 0;

}Arrays in C++ do not perform automatic bounds checking. Accessing elements beyond an array’s size causes undefined behavior, which might crash immediately, might corrupt other data, or might appear to work until some later point when the corrupted data causes problems. Off-by-one errors in loops are particularly common—remember that arrays are zero-indexed and an array of size five has valid indices zero through four, not one through five. Always double-check your loop conditions and array accesses to ensure they stay within bounds.

Pointer mistakes represent some of the most confusing errors for beginners:

#include <iostream>

void demonstrateNullPointer() {

// MISTAKE: Dereferencing null pointer

int* ptr = nullptr;

// std::cout << *ptr << std::endl; // Crash! Dereferencing null

// CORRECT: Check pointer before dereferencing

if (ptr != nullptr) {

std::cout << "Pointer value: " << *ptr << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Pointer is null" << std::endl;

}

}

void demonstrateUninitializedPointer() {

// MISTAKE: Uninitialized pointer

int* badPtr; // Points to random memory location

// *badPtr = 42; // Crash or corruption! Writing to random memory

// CORRECT: Initialize pointer

int value = 42;

int* goodPtr = &value;

*goodPtr = 100; // Safe - points to valid variable

std::cout << "Value through pointer: " << *goodPtr << std::endl;

}

void demonstrateDanglingPointer() {

int* ptr;

{

int localVar = 42;

ptr = &localVar; // MISTAKE: Pointer to local variable

} // localVar destroyed here

// *ptr is now dangling - points to destroyed variable

// std::cout << *ptr << std::endl; // Undefined behavior!

}

void demonstrateMemoryLeak() {

// MISTAKE: Memory leak - allocated but never freed

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

int* leak = new int(i);

// Never delete leak - memory leaks!

}

// CORRECT: Always delete what you new

int* proper = new int(42);

std::cout << "Allocated value: " << *proper << std::endl;

delete proper; // Clean up

proper = nullptr; // Good practice - prevent use after delete

}

void demonstrateDeleteMistakes() {

int* single = new int(42);

int* array = new int[5];

// MISTAKE: Using delete instead of delete[]

// delete array; // Wrong! Should be delete[]

// CORRECT: Match new with delete, new[] with delete[]

delete single;

delete[] array;

// MISTAKE: Double delete

int* ptr = new int(10);

delete ptr;

// delete ptr; // Crash! Deleting already-freed memory

}

int main() {

demonstrateNullPointer();

demonstrateUninitializedPointer();

demonstrateDanglingPointer();

demonstrateMemoryLeak();

demonstrateDeleteMistakes();

return 0;

}Pointer errors cause some of the most frustrating bugs because they often don’t fail immediately at the point of error. Dereferencing null or uninitialized pointers typically crashes the program, making them relatively easy to find. Dangling pointers that point to destroyed objects often appear to work because the memory hasn’t been reused yet, then fail mysteriously when that memory gets reused. Memory leaks don’t cause immediate problems but slowly consume available memory until the system runs out. Always initialize pointers, check them before dereferencing, match new with delete and new[] with delete[], and set pointers to nullptr after deleting to prevent accidental reuse.

Integer division is a subtle but common source of incorrect calculations:

#include <iostream>

void demonstrateIntegerDivision() {

// MISTAKE: Integer division when floating-point needed

int a = 7;

int b = 2;

double result1 = a / b; // Division happens as integers (3), then converts to double (3.0)

std::cout << "7 / 2 (wrong) = " << result1 << std::endl;

// CORRECT: Cast to double before division

double result2 = static_cast<double>(a) / b;

std::cout << "7 / 2 (correct) = " << result2 << std::endl;

// MISTAKE: Average calculation with integer division

int total = 100;

int count = 7;

double average1 = total / count; // Integer division!

std::cout << "Average (wrong) = " << average1 << std::endl;

// CORRECT: Ensure floating-point division

double average2 = static_cast<double>(total) / count;

std::cout << "Average (correct) = " << average2 << std::endl;

// MISTAKE: Percentage calculation

int passed = 17;

int total_students = 20;

double percentage1 = (passed / total_students) * 100; // Division gives 0!

std::cout << "Percentage (wrong) = " << percentage1 << "%" << std::endl;

// CORRECT: Cast to double

double percentage2 = (static_cast<double>(passed) / total_students) * 100;

std::cout << "Percentage (correct) = " << percentage2 << "%" << std::endl;

}

int main() {

demonstrateIntegerDivision();

return 0;

}When both operands of division are integers, C++ performs integer division that discards the remainder, even if you assign the result to a floating-point variable. The division happens first with integer operands, producing an integer result, then that integer converts to floating-point for assignment. To get floating-point division, ensure at least one operand is floating-point type through casting or by using floating-point literals like two point zero instead of two.

Comparison operators are frequently confused with assignment:

#include <iostream>

void demonstrateAssignmentVsComparison() {

int value = 10;

// MISTAKE: Assignment in condition

if (value = 5) { // Assigns 5 to value, then evaluates as true

std::cout << "This always executes! Value is now: " << value << std::endl;

}

// CORRECT: Comparison in condition

value = 10; // Reset

if (value == 5) { // Compares value with 5

std::cout << "This doesn't execute" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Value is not 5, it's: " << value << std::endl;

}

// MISTAKE: Confusing = with ==

int score = 85;

if (score = 90) { // Sets score to 90, always true

std::cout << "Score is now: " << score << std::endl; // Prints 90!

}

}

void demonstrateFloatingPointComparison() {

double a = 0.1 + 0.2;

double b = 0.3;

// MISTAKE: Direct floating-point equality comparison

if (a == b) {

std::cout << "Equal" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Not equal due to floating-point precision!" << std::endl;

std::cout << "a = " << a << std::endl;

std::cout << "b = " << b << std::endl;

}

// CORRECT: Compare with epsilon tolerance

const double epsilon = 0.00001;

if (std::abs(a - b) < epsilon) {

std::cout << "Equal within tolerance" << std::endl;

}

}

int main() {

demonstrateAssignmentVsComparison();

std::cout << std::endl;

demonstrateFloatingPointComparison();

return 0;

}Using a single equals sign in a condition performs assignment rather than comparison, which is almost never what you want. The assignment succeeds and returns the assigned value, which then gets converted to boolean for the condition check. Many compilers warn about this pattern, but the warning is easy to miss. Double-check your conditions to ensure you’re using double equals for comparison. Additionally, comparing floating-point numbers for exact equality often fails due to precision limitations, so compare floating-point values using a small tolerance epsilon instead of exact equality.

Scope and lifetime mistakes cause subtle bugs:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

int* createDanglingPointer() {

// MISTAKE: Returning pointer to local variable

int localValue = 42;

return &localValue; // localValue destroyed when function returns!

}

std::vector<int>* createDanglingVectorPointer() {

// MISTAKE: Returning pointer to local object

std::vector<int> localVector = {1, 2, 3};

return &localVector; // localVector destroyed at end of function!

}

int* createProperPointer() {

// CORRECT: Dynamically allocate (caller must delete)

int* ptr = new int(42);

return ptr;

}

std::vector<int> returnByValue() {

// CORRECT: Return by value (no dangling reference)

std::vector<int> result = {1, 2, 3};

return result; // Efficient with move semantics

}

void demonstrateScopeMistake() {

int* ptr;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

int value = i * 10;

ptr = &value; // MISTAKE: ptr points to loop variable

} // value destroyed here

// *ptr is dangling - points to destroyed variable

}

int main() {

// int* badPtr = createDanglingPointer();

// std::cout << *badPtr << std::endl; // Undefined behavior!

int* goodPtr = createProperPointer();

std::cout << "Proper pointer: " << *goodPtr << std::endl;

delete goodPtr; // Clean up

std::vector<int> vec = returnByValue();

std::cout << "Vector size: " << vec.size() << std::endl;

return 0;

}Returning pointers or references to local variables creates dangling pointers because local variables are destroyed when the function returns. The pointer or reference points to memory that no longer contains the intended value and might be reused for other purposes. Either return by value, which is efficient with modern move semantics, or dynamically allocate memory that persists beyond the function, though this requires the caller to manage cleanup.

Let me show you a comprehensive example demonstrating multiple common mistakes and their corrections:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

// MISTAKES DEMONSTRATION

class BadStudent {

public:

std::string name;

int age;

double gpa;

int* grades; // Pointer to dynamic array

// MISTAKE: No initialization in constructor

BadStudent(std::string n) {

name = n; // age and gpa uninitialized!

// grades not initialized - dangling pointer!

}

// MISTAKE: No destructor - memory leak from grades array

};

// CORRECT VERSION

class GoodStudent {

private:

std::string name;

int age;

std::vector<int> grades; // Use vector instead of raw array

public:

// CORRECT: Initialize all members

GoodStudent(const std::string& n, int a = 0)

: name(n), age(a) { // Member initializer list

}

// CORRECT: Use vector which manages its own memory

void addGrade(int grade) {

grades.push_back(grade);

}

double calculateAverage() const {

if (grades.empty()) return 0.0;

int sum = 0;

for (int grade : grades) {

sum += grade;

}

// CORRECT: Cast to avoid integer division

return static_cast<double>(sum) / grades.size();

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "Student: " << name << ", Age: " << age << std::endl;

std::cout << "Average: " << calculateAverage() << std::endl;

}

};

void demonstrateCommonMistakes() {

// MISTAKE: Mixing up array size and index

int numbers[10];

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

numbers[i] = i; // Correct

}

// int lastElement = numbers[10]; // WRONG! Index 10 is out of bounds

int lastElement = numbers[9]; // CORRECT - last valid index is 9

// MISTAKE: Forgetting break in switch

int choice = 1;

switch (choice) {

case 1:

std::cout << "Choice 1" << std::endl;

// MISTAKE: No break - falls through!

case 2:

std::cout << "Choice 2" << std::endl;

break;

}

// CORRECT: Include break statements

switch (choice) {

case 1:

std::cout << "Only choice 1" << std::endl;

break;

case 2:

std::cout << "Only choice 2" << std::endl;

break;

}

}

int main() {

GoodStudent student("Alice", 20);

student.addGrade(85);

student.addGrade(92);

student.addGrade(78);

student.display();

std::cout << std::endl;

demonstrateCommonMistakes();

return 0;

}This example shows how multiple mistakes compound—the BadStudent class has uninitialized members, uses raw pointers without proper management, and leaks memory by not cleaning up dynamically allocated arrays. The GoodStudent class fixes these issues by initializing all members, using vectors instead of raw arrays for automatic memory management, and properly handling division to avoid integer truncation. Building good habits from the start prevents these issues from becoming ingrained patterns.

Understanding compiler warnings helps catch many mistakes early. Modern compilers warn about uninitialized variables, unused variables, assignments in conditions, and many other common errors. Always compile with warnings enabled and treat warnings as errors to fix during development. The warnings exist because experienced programmers recognized patterns that usually indicate bugs.

Debugging strategies help when mistakes slip through. When your program crashes, note where it crashes and work backward to understand what could cause that failure. When calculations produce wrong results, add output statements to track intermediate values and verify assumptions. When behavior is unpredictable, look for uninitialized variables or out-of-bounds access. Systematic debugging beats random code changes every time.

Key Takeaways

Common beginner mistakes in C++ fall into recognizable patterns that you can learn to avoid. Always initialize variables when you declare them to prevent using garbage values. Always check array and string bounds to prevent memory corruption and undefined behavior. Initialize pointers to nullptr or valid addresses, check them before dereferencing, and set them to nullptr after deletion. Remember that arrays are zero-indexed and an array of size N has valid indices zero through N minus one.

Integer division truncates the remainder even when assigning to floating-point variables because the division happens first with integer operands. Cast at least one operand to floating-point type to get accurate division results. Use double equals for comparison, not single equals which performs assignment. Compare floating-point numbers using epsilon tolerance rather than exact equality due to precision limitations.

Local variables are destroyed when leaving their scope, making pointers and references to them invalid. Return by value or dynamically allocate memory when you need data to persist beyond a function. Use vectors and smart pointers instead of raw pointers and arrays when possible for automatic memory management. Enable compiler warnings and treat them seriously because they catch many common mistakes. Learn to recognize error patterns so you can debug systematically rather than randomly changing code hoping for success.