Up to this point, you’ve been writing procedural code where programs consist of functions that operate on data, with the data and functions living separately. You declare variables to hold information and write functions to process that information, but the data and the operations that work on it remain disconnected. This procedural approach works fine for small programs, but as programs grow larger and more complex, keeping track of which functions should work with which data becomes increasingly difficult. Object-oriented programming solves this problem by bundling data and the functions that operate on it together into cohesive units called objects, fundamentally changing how you think about program design from a collection of procedures to a community of interacting objects.

Think of object-oriented programming like designing a car. In procedural programming, you would have separate pieces scattered everywhere—an engine here, wheels there, a steering mechanism over there—along with a collection of instructions for how to operate each piece. Anyone wanting to drive the car would need to remember which functions work with which components and in what order to call them. Object-oriented programming instead packages the steering wheel, gas pedal, brake pedal, and dashboard into a cohesive driver interface that hides the complexity of the engine, transmission, and other internal mechanisms. You interact with well-defined interfaces without needing to understand or manipulate the internal details, and the car itself ensures its components work together correctly.

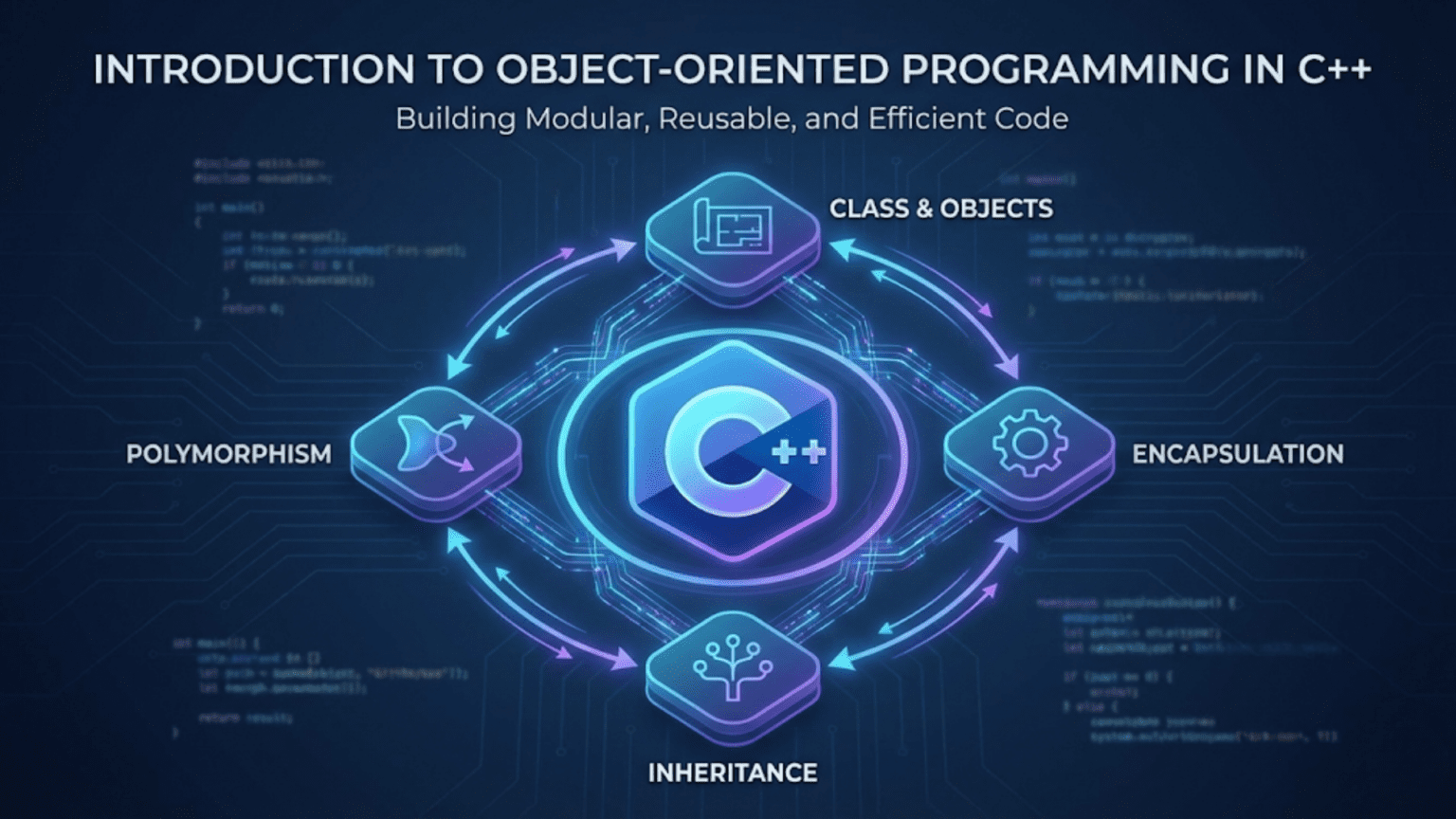

The power of object-oriented programming comes from four fundamental principles that work together to create maintainable, reusable, extensible code. Encapsulation bundles data with the methods that operate on it while hiding internal details behind public interfaces. Inheritance enables creating new types based on existing types, sharing common functionality while adding specialized behavior. Polymorphism allows objects of different types to be treated uniformly through common interfaces, with each object responding appropriately to operations based on its actual type. Abstraction focuses on essential characteristics while hiding unnecessary complexity, making systems easier to understand and use. Understanding these principles transforms how you design software, enabling you to create programs that naturally map to real-world concepts and remain manageable even as they grow large and complex.

Let me start by showing you a simple example that contrasts procedural and object-oriented approaches to the same problem:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <cmath>

// PROCEDURAL APPROACH - data and functions separate

struct Point {

double x;

double y;

};

// Functions that work with Point data

double calculateDistance(const Point& p1, const Point& p2) {

double dx = p1.x - p2.x;

double dy = p1.y - p2.y;

return std::sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy);

}

void displayPoint(const Point& p) {

std::cout << "(" << p.x << ", " << p.y << ")";

}

void movePoint(Point& p, double dx, double dy) {

p.x += dx;

p.y += dy;

}

// OBJECT-ORIENTED APPROACH - data and functions together

class PointOOP {

private:

double x;

double y;

public:

// Constructor - initializes object

PointOOP(double xVal, double yVal) : x(xVal), y(yVal) {}

// Methods - functions that belong to the object

double distanceTo(const PointOOP& other) const {

double dx = x - other.x;

double dy = y - other.y;

return std::sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy);

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "(" << x << ", " << y << ")";

}

void move(double dx, double dy) {

x += dx;

y += dy;

}

// Accessors

double getX() const { return x; }

double getY() const { return y; }

};

int main() {

std::cout << "=== Procedural Approach ===" << std::endl;

Point p1 = {3, 4};

Point p2 = {6, 8};

std::cout << "Point 1: ";

displayPoint(p1);

std::cout << std::endl;

std::cout << "Point 2: ";

displayPoint(p2);

std::cout << std::endl;

double dist = calculateDistance(p1, p2);

std::cout << "Distance: " << dist << std::endl;

movePoint(p1, 1, 1);

std::cout << "After moving Point 1: ";

displayPoint(p1);

std::cout << std::endl << std::endl;

std::cout << "=== Object-Oriented Approach ===" << std::endl;

PointOOP point1(3, 4);

PointOOP point2(6, 8);

std::cout << "Point 1: ";

point1.display();

std::cout << std::endl;

std::cout << "Point 2: ";

point2.display();

std::cout << std::endl;

double distance = point1.distanceTo(point2);

std::cout << "Distance: " << distance << std::endl;

point1.move(1, 1);

std::cout << "After moving Point 1: ";

point1.display();

std::cout << std::endl;

return 0;

}The procedural approach keeps data in a simple struct and operations in separate functions. You must remember which functions work with Point data and explicitly pass points to those functions. The object-oriented approach encapsulates the x and y coordinates together with the operations that work on them inside a class. Instead of calling calculateDistance and passing both points, you call point one dot distance to point two, making the relationship between data and operations explicit. The methods belong to the object, so you cannot accidentally call them on inappropriate data. This bundling of data and behavior represents encapsulation, the first fundamental principle of object-oriented programming.

Encapsulation provides more than just organizational benefits. Notice that the x and y members in PointOOP are private, meaning code outside the class cannot access them directly. This information hiding protects the internal representation from external interference. If you later decide to store points using polar coordinates internally instead of Cartesian, you can change the implementation without affecting any code that uses the class, as long as you maintain the same public interface. The class controls how its data is accessed and modified, enabling it to maintain invariants and validate inputs:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class BankAccount {

private:

std::string accountNumber;

double balance;

// Private helper method

bool isValidAmount(double amount) const {

return amount > 0;

}

public:

// Constructor

BankAccount(const std::string& accNum, double initialBalance)

: accountNumber(accNum), balance(0) {

if (initialBalance > 0) {

balance = initialBalance;

}

}

// Public interface - controlled access to private data

bool deposit(double amount) {

if (!isValidAmount(amount)) {

std::cout << "Invalid deposit amount" << std::endl;

return false;

}

balance += amount;

std::cout << "Deposited $" << amount << ". New balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

return true;

}

bool withdraw(double amount) {

if (!isValidAmount(amount)) {

std::cout << "Invalid withdrawal amount" << std::endl;

return false;

}

if (amount > balance) {

std::cout << "Insufficient funds" << std::endl;

return false;

}

balance -= amount;

std::cout << "Withdrew $" << amount << ". New balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

return true;

}

double getBalance() const {

return balance;

}

void displayInfo() const {

std::cout << "Account: " << accountNumber << ", Balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

BankAccount account("ACC001", 1000);

account.displayInfo();

// Can only interact through public methods

account.deposit(500);

account.withdraw(200);

account.withdraw(2000); // Fails - insufficient funds

// Cannot directly access private members

// account.balance = 1000000; // Compilation error!

// Must use public interface

std::cout << "Current balance: $" << account.getBalance() << std::endl;

return 0;

}The BankAccount class demonstrates encapsulation protecting data integrity. The balance is private, so external code cannot arbitrarily change it. All modifications must go through the public deposit and withdraw methods, which validate the amounts and ensure the balance never goes negative. This controlled access prevents bugs caused by invalid state that would be possible if balance were public. The class maintains the invariant that balance always represents a valid account state, and encapsulation enforces this invariant by controlling all access to the data.

Inheritance represents the second fundamental principle, enabling you to create new classes based on existing ones. The derived class inherits all the data members and methods from the base class while adding its own specialized functionality:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

// Base class - general animal characteristics

class Animal {

protected:

std::string name;

int age;

public:

Animal(const std::string& n, int a) : name(n), age(a) {}

void eat() const {

std::cout << name << " is eating." << std::endl;

}

void sleep() const {

std::cout << name << " is sleeping." << std::endl;

}

void displayInfo() const {

std::cout << "Name: " << name << ", Age: " << age << std::endl;

}

};

// Derived class - specialized for dogs

class Dog : public Animal {

private:

std::string breed;

public:

Dog(const std::string& n, int a, const std::string& b)

: Animal(n, a), breed(b) {}

// Additional behavior specific to dogs

void bark() const {

std::cout << name << " says: Woof! Woof!" << std::endl;

}

void fetch() const {

std::cout << name << " is fetching the ball!" << std::endl;

}

void displayBreed() const {

std::cout << name << " is a " << breed << std::endl;

}

};

// Another derived class - specialized for cats

class Cat : public Animal {

private:

bool isIndoor;

public:

Cat(const std::string& n, int a, bool indoor)

: Animal(n, a), isIndoor(indoor) {}

void meow() const {

std::cout << name << " says: Meow!" << std::endl;

}

void purr() const {

std::cout << name << " is purring contentedly." << std::endl;

}

void displayLocation() const {

std::cout << name << " is an " << (isIndoor ? "indoor" : "outdoor") << " cat" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

Dog myDog("Buddy", 3, "Golden Retriever");

Cat myCat("Whiskers", 2, true);

std::cout << "=== Dog ===" << std::endl;

myDog.displayInfo(); // Inherited from Animal

myDog.displayBreed(); // Dog-specific

myDog.eat(); // Inherited from Animal

myDog.bark(); // Dog-specific

myDog.fetch(); // Dog-specific

std::cout << "\n=== Cat ===" << std::endl;

myCat.displayInfo(); // Inherited from Animal

myCat.displayLocation(); // Cat-specific

myCat.sleep(); // Inherited from Animal

myCat.meow(); // Cat-specific

myCat.purr(); // Cat-specific

return 0;

}Inheritance creates an “is-a” relationship where a Dog is an Animal and a Cat is an Animal. Both derived classes automatically get all the functionality from Animal, so they can eat and sleep without redefining those behaviors. Each derived class then adds its own specialized functionality. This code reuse eliminates duplication while establishing clear hierarchical relationships between types. If you add new functionality to Animal, all derived classes automatically inherit it, making it easy to extend common behavior across an entire hierarchy.

Polymorphism, the third principle, enables treating objects of different types uniformly through a common interface, with each object responding appropriately based on its actual type:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

class Shape {

protected:

std::string color;

public:

Shape(const std::string& c) : color(c) {}

// Virtual function - can be overridden in derived classes

virtual double getArea() const {

return 0;

}

virtual void draw() const {

std::cout << "Drawing a " << color << " shape" << std::endl;

}

virtual ~Shape() {}

};

class Circle : public Shape {

private:

double radius;

public:

Circle(const std::string& c, double r) : Shape(c), radius(r) {}

// Override getArea for circles

double getArea() const override {

return 3.14159 * radius * radius;

}

// Override draw for circles

void draw() const override {

std::cout << "Drawing a " << color << " circle with radius " << radius << std::endl;

}

};

class Rectangle : public Shape {

private:

double width;

double height;

public:

Rectangle(const std::string& c, double w, double h)

: Shape(c), width(w), height(h) {}

double getArea() const override {

return width * height;

}

void draw() const override {

std::cout << "Drawing a " << color << " rectangle " << width << "x" << height << std::endl;

}

};

// Function that works with any Shape polymorphically

void processShape(const Shape& shape) {

shape.draw();

std::cout << "Area: " << shape.getArea() << std::endl;

}

int main() {

Circle circle("red", 5.0);

Rectangle rect("blue", 4.0, 6.0);

std::cout << "=== Processing Circle ===" << std::endl;

processShape(circle);

std::cout << "\n=== Processing Rectangle ===" << std::endl;

processShape(rect);

// Polymorphic collection

std::cout << "\n=== Processing Multiple Shapes ===" << std::endl;

std::vector<Shape*> shapes;

shapes.push_back(&circle);

shapes.push_back(&rect);

for (const auto& shape : shapes) {

shape->draw();

std::cout << "Area: " << shape->getArea() << std::endl;

std::cout << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}Polymorphism enables the processShape function to work with any Shape, whether it’s a Circle or Rectangle. When you call shape dot draw or shape dot get area, the correct version executes based on the actual object type, not the reference type. This runtime binding means you can write code that operates on base class interfaces without knowing the specific derived types, making programs extensible. You can add new shape types without modifying processShape or any other code that works with shapes generically.

Abstraction, the fourth principle, means focusing on what an object does rather than how it does it, hiding implementation details behind simplified interfaces:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

#include <algorithm>

class StudentGradeManager {

private:

std::string studentName;

std::vector<double> grades;

// Private implementation details

double calculateSum() const {

double sum = 0;

for (double grade : grades) {

sum += grade;

}

return sum;

}

public:

StudentGradeManager(const std::string& name) : studentName(name) {}

// Public interface - abstracts away internal complexity

void addGrade(double grade) {

if (grade >= 0 && grade <= 100) {

grades.push_back(grade);

std::cout << "Grade " << grade << " added for " << studentName << std::endl;

}

}

double getAverage() const {

if (grades.empty()) return 0.0;

return calculateSum() / grades.size();

}

char getLetterGrade() const {

double avg = getAverage();

if (avg >= 90) return 'A';

if (avg >= 80) return 'B';

if (avg >= 70) return 'C';

if (avg >= 60) return 'D';

return 'F';

}

void displayReport() const {

std::cout << "\n=== Grade Report for " << studentName << " ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Number of grades: " << grades.size() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Average: " << getAverage() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Letter grade: " << getLetterGrade() << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

StudentGradeManager student("Alice Johnson");

student.addGrade(85);

student.addGrade(92);

student.addGrade(78);

student.addGrade(88);

student.displayReport();

return 0;

}The StudentGradeManager class abstracts grade management complexity behind a simple interface. Users call add grade, get average, and display report without needing to know that grades are stored in a vector or how the average is calculated. The implementation details are hidden in private methods. This abstraction makes the class easy to use while allowing the internal implementation to change without affecting code that uses the class. You could switch from a vector to an array or change how averages are calculated without breaking any code that uses the public interface.

Let me show you a more comprehensive example that demonstrates all four OOP principles working together in a realistic scenario:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <memory>

// Base class demonstrating abstraction and encapsulation

class Employee {

protected:

std::string name;

int employeeId;

double baseSalary;

public:

Employee(const std::string& n, int id, double salary)

: name(n), employeeId(id), baseSalary(salary) {}

// Virtual destructor for polymorphism

virtual ~Employee() {}

// Pure virtual function - derived classes must implement

virtual double calculatePay() const = 0;

// Virtual function with default implementation

virtual void displayInfo() const {

std::cout << "Employee: " << name << std::endl;

std::cout << "ID: " << employeeId << std::endl;

std::cout << "Monthly Pay: $" << calculatePay() << std::endl;

}

std::string getName() const { return name; }

int getId() const { return employeeId; }

};

// Inheritance - Manager is-an Employee

class Manager : public Employee {

private:

double bonus;

int teamSize;

public:

Manager(const std::string& n, int id, double salary, double b, int team)

: Employee(n, id, salary), bonus(b), teamSize(team) {}

// Polymorphism - override calculatePay

double calculatePay() const override {

return baseSalary + bonus;

}

// Polymorphism - extend displayInfo

void displayInfo() const override {

Employee::displayInfo(); // Call base class version

std::cout << "Bonus: $" << bonus << std::endl;

std::cout << "Team Size: " << teamSize << std::endl;

}

void conductMeeting() const {

std::cout << name << " is conducting a team meeting" << std::endl;

}

};

class SalesRep : public Employee {

private:

double commissionRate;

double salesTotal;

public:

SalesRep(const std::string& n, int id, double salary, double rate)

: Employee(n, id, salary), commissionRate(rate), salesTotal(0) {}

double calculatePay() const override {

return baseSalary + (salesTotal * commissionRate);

}

void displayInfo() const override {

Employee::displayInfo();

std::cout << "Commission Rate: " << (commissionRate * 100) << "%" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Sales Total: $" << salesTotal << std::endl;

}

void recordSale(double amount) {

salesTotal += amount;

std::cout << name << " recorded sale of $" << amount << std::endl;

}

};

class Developer : public Employee {

private:

std::string programmingLanguage;

int projectsCompleted;

public:

Developer(const std::string& n, int id, double salary, const std::string& lang)

: Employee(n, id, salary), programmingLanguage(lang), projectsCompleted(0) {}

double calculatePay() const override {

// Base salary plus bonus for completed projects

return baseSalary + (projectsCompleted * 500);

}

void displayInfo() const override {

Employee::displayInfo();

std::cout << "Language: " << programmingLanguage << std::endl;

std::cout << "Projects Completed: " << projectsCompleted << std::endl;

}

void completeProject() {

projectsCompleted++;

std::cout << name << " completed a project in " << programmingLanguage << std::endl;

}

};

// Class demonstrating composition and abstraction

class Company {

private:

std::string companyName;

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<Employee>> employees;

public:

Company(const std::string& name) : companyName(name) {}

void hireEmployee(std::shared_ptr<Employee> employee) {

employees.push_back(employee);

std::cout << employee->getName() << " hired at " << companyName << std::endl;

}

// Polymorphism - works with any Employee type

void displayPayroll() const {

std::cout << "\n=== " << companyName << " Payroll ===" << std::endl;

double totalPayroll = 0;

for (const auto& employee : employees) {

employee->displayInfo();

std::cout << std::endl;

totalPayroll += employee->calculatePay();

}

std::cout << "Total Monthly Payroll: $" << totalPayroll << std::endl;

}

void displayEmployeeCount() const {

std::cout << companyName << " has " << employees.size() << " employees" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

Company techCorp("TechCorp Inc.");

// Create different types of employees

auto manager = std::make_shared<Manager>("Alice Johnson", 1001, 8000, 2000, 5);

auto sales = std::make_shared<SalesRep>("Bob Smith", 1002, 5000, 0.05);

auto dev = std::make_shared<Developer>("Carol White", 1003, 7000, "C++");

// Hire employees

techCorp.hireEmployee(manager);

techCorp.hireEmployee(sales);

techCorp.hireEmployee(dev);

std::cout << std::endl;

techCorp.displayEmployeeCount();

// Perform type-specific actions

std::cout << "\n=== Employee Activities ===" << std::endl;

manager->conductMeeting();

sales->recordSale(10000);

sales->recordSale(15000);

dev->completeProject();

dev->completeProject();

// Polymorphic payroll display

techCorp.displayPayroll();

return 0;

}This comprehensive example demonstrates all four OOP principles working in harmony. Encapsulation protects each employee’s internal data while exposing appropriate public interfaces. Inheritance creates a hierarchy where Manager, SalesRep, and Developer inherit common functionality from Employee while adding specialized behavior. Polymorphism enables the Company class to work with all employee types uniformly through the Employee base class interface. Abstraction hides implementation complexity, presenting clean interfaces for hiring employees and displaying payroll. The four principles work together to create code that is organized, maintainable, extensible, and maps naturally to the problem domain.

Understanding when to use object-oriented programming helps you apply it effectively. Use OOP when you have entities with both data and behavior that naturally group together, when you have hierarchical relationships among types with shared and specialized functionality, when you need to hide implementation details behind stable interfaces, or when you want extensibility where new types can be added without modifying existing code. Not every program needs object-oriented design, but recognizing scenarios where OOP provides clear benefits enables making informed architectural decisions.

Key Takeaways

Object-oriented programming organizes code around objects that bundle data with the operations that work on it, fundamentally shifting program design from collections of procedures to communities of interacting objects. Four fundamental principles guide object-oriented design. Encapsulation bundles data and methods together while hiding internal details, protecting data integrity and enabling implementation changes without breaking external code. Inheritance creates hierarchical relationships where derived classes inherit functionality from base classes while adding specialized behavior, promoting code reuse.

Polymorphism enables treating objects of different types uniformly through common interfaces, with each object responding appropriately based on its actual type determined at runtime through virtual functions. Abstraction focuses on essential characteristics while hiding implementation complexity, presenting simplified interfaces that make systems easier to understand and use. These principles work together synergistically to create maintainable, reusable, and extensible code.

Object-oriented programming excels when entities naturally have both state and behavior that should group together, when hierarchical type relationships exist with shared and specialized functionality, when implementation details should hide behind stable interfaces, or when extensibility matters where new types must integrate without modifying existing code. Understanding these fundamental OOP principles transforms how you design software, enabling programs that map naturally to problem domains while remaining manageable as they grow in size and complexity.