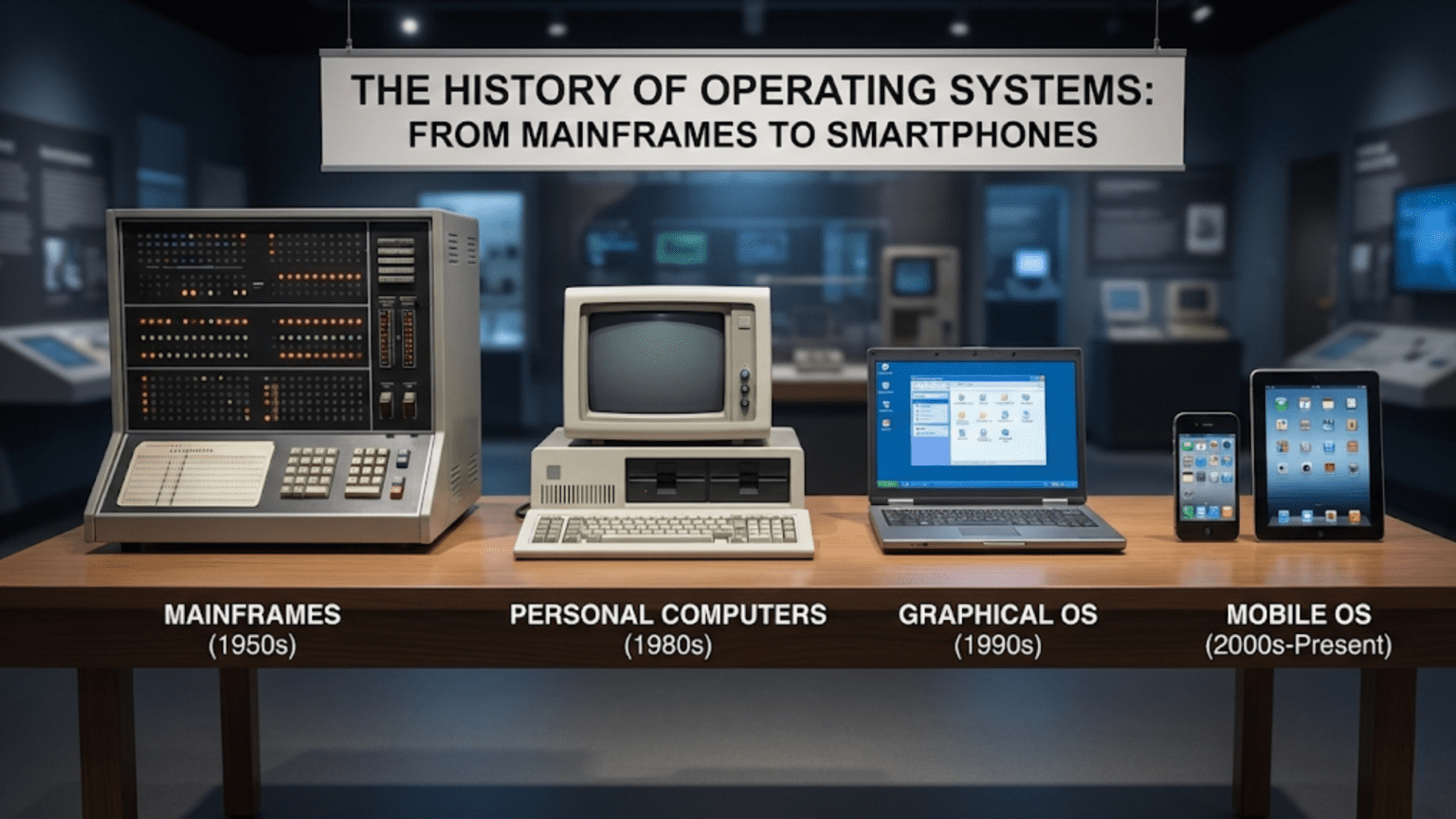

The Evolution of Software That Makes Computers Usable

The operating system you use today, whether it runs on your smartphone, laptop, or tablet, represents the culmination of more than seventy years of innovation, experimentation, and gradual refinement. The sophisticated multitasking capabilities, graphical interfaces, and seamless networking that you take for granted did not emerge fully formed but evolved through decades of development as engineers grappled with increasingly complex computing challenges. Understanding this history reveals not just interesting technical stories but also the fundamental principles that shaped modern computing. The decisions made by operating system pioneers in the 1960s and 1970s still influence how your computer works today, and the problems they solved remain recognizable even as the scale and context have changed dramatically.

Tracing operating system history means following the co-evolution of hardware and software as each advanced in response to the other’s capabilities and limitations. Early computers had no operating systems at all because the machines were so expensive and rare that dedicating one person’s full attention to running a single program seemed perfectly reasonable. As computers became more capable and numerous, the waste of having expensive hardware sit idle while operators manually loaded programs became unacceptable, spurring the development of software that could manage the machine automatically. This pattern repeated throughout computing history as new hardware capabilities enabled new software approaches, which in turn drove demand for enhanced hardware. The story of operating systems is inseparable from the broader story of computing itself.

The Beginning: Computers Without Operating Systems

In the 1940s and early 1950s, the first electronic computers operated without anything we would recognize as an operating system. These room-sized machines built from vacuum tubes performed calculations that would have taken humans days or weeks in mere hours, but using them was extraordinarily difficult. Programmers wrote instructions in machine language, which meant directly specifying the numeric codes that the hardware understood. They entered these programs by flipping switches on the computer’s front panel or using punched cards, which were cardboard cards with holes punched in specific patterns that represented instructions and data.

Running a program on these early computers was an all-consuming manual process. The programmer would reserve the entire computer for a block of time, perhaps several hours. When their time arrived, they would physically go to the computer room, load their program using whatever input method the machine provided, start execution, and wait for results to print or display. If the program had bugs, which was extremely common given the difficulty of programming in machine language, the programmer would make corrections and have to schedule another session to try again. The computer sat completely idle between programs while the next user prepared to load their work.

This manual operation wasted tremendous amounts of expensive computer time. While the hardware was capable of executing millions of instructions per second, it spent most of its time waiting for humans to perform slow manual tasks like mounting magnetic tapes, loading punched cards, or copying results. The economics of early computing made this waste intolerable. A single computer might cost millions of dollars in today’s money and serve an entire organization’s computing needs. Finding ways to keep these precious machines busy became an urgent priority.

Batch Processing: The First Operating Systems

The solution to manual operation’s inefficiency came in the form of batch processing systems that automated the transition between programs. Rather than having users interact directly with the computer, batch systems collected multiple programs into a batch that the computer would process sequentially without human intervention. An operator would gather submitted programs, load them all into the computer’s card reader at once, and the system would automatically run each program in sequence, printing results and moving to the next program when each finished.

The software that managed this batch processing represented the first true operating systems. These systems could read job control cards that specified what resources each program needed, load programs into memory, start their execution, collect output, and transition to the next program automatically. This automation dramatically improved computer utilization because the transition time between programs shrank from minutes or hours with manual operation to seconds with batch processing. The computer spent far more time doing useful computation and far less time idle waiting for the next program.

Batch processing introduced several concepts that remain fundamental to operating systems today. The system needed to protect itself from user programs that might crash or run forever, so early batch systems implemented time limits and memory protection. They tracked resource usage to bill departments for computer time consumed. They managed multiple input and output devices simultaneously. These capabilities might seem primitive compared to modern operating systems, but they established the principle that software could manage hardware resources automatically, enabling efficient sharing of expensive equipment among many users.

Multiprogramming: Running Multiple Programs Simultaneously

As computers became faster and memory larger, a new inefficiency emerged. Programs often waited for slow input and output operations to complete, and during these waits the processor sat idle even though other programs might be ready to run. A program reading data from magnetic tape might wait milliseconds while the tape physically moved to the right position, during which time the processor could execute thousands of instructions from another program. This observation led to multiprogramming systems that could keep multiple programs loaded in memory simultaneously and switch between them, running one program while another waited for input or output.

Multiprogramming required more sophisticated operating systems than batch processing because now the system had to manage multiple programs at once rather than just one at a time. Memory had to be divided among the competing programs, ensuring each had its own space that others could not access. The processor had to be scheduled fairly so all programs made progress rather than one monopolizing the CPU. Input and output operations from different programs had to be coordinated so they did not conflict. These challenges drove rapid operating system development in the 1960s as researchers and engineers developed techniques that enabled safe, efficient multiprogramming.

The operating systems developed during this era established many principles still used today. Memory protection prevented programs from accessing each other’s memory. Process scheduling algorithms determined which program should run at any moment. Interrupt handling allowed devices to notify the processor when input or output completed without requiring constant polling. These techniques transformed computers from machines that ran one program at a time into systems capable of juggling dozens of programs simultaneously, though users still could not interact with running programs directly.

Time-Sharing: The Revolution of Interactive Computing

Batch processing and multiprogramming improved efficiency but offered no interactivity. Users submitted programs and received results hours or days later with no ability to debug problems immediately or explore computational questions interactively. Time-sharing systems developed in the mid-1960s revolutionized computing by allowing multiple users to interact with the computer simultaneously through terminals, with each user feeling like they had a dedicated computer despite actually sharing it with many others.

The Compatible Time-Sharing System developed at MIT demonstrated that time-sharing was practical and desirable. Multiple users could log in simultaneously from teletypes or video terminals, running programs, editing text, and seeing results immediately. The operating system rapidly switched among user programs, giving each one a slice of time that was brief enough that all users perceived nearly instant response. This interactivity transformed programming from a batch-oriented process requiring hours between attempts to an interactive dialogue where programmers could try changes and immediately see results.

MULTICS, which stood for Multiplexed Information and Computing Service, was an ambitious time-sharing system developed jointly by MIT, General Electric, and Bell Labs starting in the mid-1960s. While MULTICS proved too complex to achieve widespread commercial success, it introduced numerous concepts that influenced later operating systems profoundly. MULTICS featured sophisticated security with access control lists, hierarchical file systems, dynamic linking of program modules, and command shells that interpreted user commands. Many of these ideas seemed exotic when introduced but became standard features of later operating systems.

Unix: Simplicity and Portability Transform Computing

The complexity and ambition of MULTICS prompted Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie at Bell Labs to pursue a radically different approach. Starting around 1969, they developed Unix based on principles of simplicity and clarity. Unix was written mostly in the C programming language, which Thompson and Ritchie were developing simultaneously, making it one of the first operating systems written in a high-level language rather than assembly language. This choice made Unix portable across different computer architectures because recompiling the C source code could target different processors, whereas assembly language was specific to particular hardware.

Unix introduced a philosophy that programs should do one thing well and should be composable through simple mechanisms. The shell command line allowed users to combine small utility programs through pipes, where the output of one program became the input to another. This enabled building complex processing workflows from simple components. The hierarchical file system organized files in tree structures familiar today. Device files made hardware devices appear as special files in the file system, allowing uniform treatment of files and devices through the same interfaces.

Unix spread rapidly through universities in the 1970s and 1980s because AT&T, which owned Bell Labs, was prohibited from selling computer systems due to antitrust concerns and thus licensed Unix cheaply to educational institutions. Students learned Unix, then brought its ideas to companies when they graduated. Variants multiplied including Berkeley Unix from the University of California, which added networking support including the TCP/IP protocols that would become fundamental to the internet. Commercial Unix systems proliferated as well, with versions from IBM, Sun Microsystems, Hewlett-Packard, and others.

The Personal Computer Revolution: MS-DOS and Early Windows

The late 1970s and early 1980s brought microcomputers that were affordable for individuals and small businesses rather than just large organizations. These personal computers needed operating systems suited to single users running one program at a time on limited hardware. MS-DOS, developed by Microsoft for the IBM PC introduced in 1981, dominated this market. DOS provided a command-line interface where users typed commands to run programs, manage files, and configure the system.

MS-DOS reflected the hardware constraints of early personal computers. It ran only one program at a time with no memory protection or multitasking. Programs had direct access to hardware with no operating system mediation, allowing maximum performance but also meaning programs could crash the entire system. The simple architecture matched the capabilities of the Intel 8088 processor in the original IBM PC, which had limited memory addressing and no memory protection features.

Microsoft Windows started as a graphical shell running on top of DOS rather than a true operating system. Windows 1.0 released in 1985 provided overlapping windows and mouse control but remained essentially a program running under DOS. Windows evolved through versions 2.0 and 3.0, becoming increasingly sophisticated while still depending on DOS underneath. Windows 3.1 released in 1992 achieved widespread popularity, bringing graphical interfaces to many users for the first time. However, these early Windows versions inherited DOS’s limitations including poor multitasking and instability from programs that misbehaved.

Macintosh: Making Graphical Interfaces Mainstream

Apple’s Macintosh, introduced in 1984, brought graphical user interfaces to mainstream users before Windows achieved similar success. The Mac System Software, later called Mac OS, provided windows, icons, menus, and a mouse-driven interface that made computers accessible to people intimidated by command-line interfaces. While earlier systems like Xerox’s Alto had demonstrated graphical interfaces, the Macintosh made them available at consumer price points and marketed them effectively.

The original Mac OS emphasized ease of use through consistency. All programs followed similar interface conventions, with menu bars at the top, similar dialog boxes, and predictable behaviors. This consistency made learning new programs easier because skills transferred between applications. The Mac established interface paradigms that became standard across all graphical operating systems including drag-and-drop, double-clicking to open items, and trash cans for deleted files.

However, early Mac OS shared architectural limitations similar to DOS and early Windows. It provided cooperative multitasking where programs had to voluntarily yield control rather than being preemptively scheduled, meaning poorly written programs could freeze the entire system. Memory protection was limited, so program crashes often required rebooting. These limitations reflected both the hardware constraints of early Macintosh computers and the priority Apple placed on ease of use over technical sophistication.

Windows NT and the Modern Windows Era

Microsoft’s Windows NT, first released in 1993, represented a complete architectural departure from DOS-based Windows. Designed by Dave Cutler, who had previously developed Digital Equipment Corporation’s VMS operating system, Windows NT featured true preemptive multitasking, memory protection, multiprocessor support, and a hardware abstraction layer that enabled portability across different processor architectures. NT was a serious operating system with robustness and security features suitable for business servers rather than just consumer desktop computers.

Windows NT existed in parallel with Windows 95 and its successors, which continued the DOS-based architecture. NT targeted business users and servers while Windows 95, 98, and Me served consumers. This split continued until Windows XP released in 2001, which unified consumer and business Windows on the NT architecture. XP’s success demonstrated that NT’s robust architecture could support both home users and enterprises, ending the distinction between consumer and professional Windows versions.

Modern Windows versions descend directly from NT, incorporating decades of refinement. Windows Vista, Windows 7, Windows 8, Windows 10, and Windows 11 all build on NT’s architectural foundation while adding features like enhanced security, better user interfaces, improved driver models, and support for new hardware capabilities. The stability and security of contemporary Windows trace to NT’s solid design, showing how fundamental architectural decisions made in the early 1990s continue influencing systems today.

Linux: Open Source Unix for Everyone

In 1991, Linus Torvalds, a Finnish computer science student, began developing a Unix-like operating system kernel that he called Linux. Unlike commercial Unix systems, Linux was freely available with source code under the GNU General Public License, which allowed anyone to use, modify, and redistribute the software. Torvalds released Linux as a collaborative project, with contributors from around the world adding features, fixing bugs, and porting it to new hardware.

Linux combined with GNU software, developed by the Free Software Foundation under Richard Stallman’s leadership, to create complete operating systems. The GNU project had developed many essential components like compilers, text editors, and system utilities but lacked a kernel. Linux filled that gap, enabling free Unix-like systems that matched or exceeded commercial Unix capabilities. Distributions like Red Hat, Debian, and Slackware packaged Linux with supporting software into complete systems suitable for various purposes.

Linux grew from a hobbyist project to enterprise-critical infrastructure over the 1990s and 2000s. Companies adopted Linux for servers because it was free, stable, customizable, and supported by a large community. Linux became dominant in web servers, supercomputers, and embedded systems. Android, now the world’s most popular operating system by number of devices, uses the Linux kernel. Linux demonstrates that open source development can produce operating systems competitive with or superior to commercial alternatives when organized effectively.

Mac OS X: Unix Meets Apple Design

Apple’s acquisition of NeXT in 1997 brought Steve Jobs back to Apple and provided technology that would transform Mac OS. NeXT had developed NeXTSTEP, an operating system based on Unix with an object-oriented programming environment and elegant graphical interface. Apple used NeXTSTEP as the foundation for Mac OS X, which replaced the aging classic Mac OS.

Mac OS X, first released in 2001, combined Unix robustness with Apple’s design sensibility. The Darwin core based on BSD Unix provided preemptive multitasking, memory protection, and all the stability classic Mac OS lacked. The Aqua user interface provided the polished graphical experience Apple users expected. The combination created an operating system that appealed to both Unix enthusiasts who valued the command-line power and consumer users who appreciated the refined interface.

macOS, as Mac OS X was later renamed, demonstrates how Unix principles established in the 1970s remain relevant decades later. The hierarchical file system, pipes, shells, and compositional philosophy work as well now as they did fifty years ago. Apple’s contribution was recognizing that Unix’s technical merits could be combined with consumer-friendly interfaces to create systems suitable for everyone from developers to artists to casual users.

Mobile Operating Systems: Computing in Your Pocket

The smartphone revolution beginning in the late 2000s required operating systems designed for touchscreens, power efficiency, and wireless connectivity rather than keyboards, mice, and wired networks. Apple’s iOS, introduced with the iPhone in 2007, and Google’s Android, released the same year, became the dominant mobile operating systems.

iOS extended macOS concepts to mobile devices, featuring touch-optimized interfaces, strict application sandboxing for security, and an app store model where all software distribution went through Apple’s review process. The iOS approach prioritized simplicity and security, with a curated experience where Apple controlled the entire stack from hardware through operating system to applications.

Android took a more open approach based on Linux and Java-influenced programming. Google provided Android as open source software that device manufacturers could customize, leading to diversity in hardware and user interfaces. The Google Play store offered application distribution with less restrictive review than Apple’s App Store. Android’s flexibility enabled its deployment on everything from budget phones to tablets to smart TVs.

Both iOS and Android incorporated lessons from decades of desktop operating system development while addressing unique mobile challenges. Power management became critical because battery life mattered far more than on plugged-in desktops. Wireless networking required sophisticated management of multiple radio types. Touch interfaces demanded different interaction paradigms than mice and keyboards. Security became paramount because phones contain extremely personal data and connect to numerous services.

The Ongoing Evolution

Operating system development continues as hardware capabilities and user needs evolve. Cloud computing raises questions about whether operating systems even need to reside on local devices or could be delivered as services from remote servers. Artificial intelligence and machine learning create demands for operating systems that efficiently manage GPUs and specialized accelerators. The Internet of Things proliferates tiny computers in appliances, sensors, and infrastructure that need lightweight operating systems adapted to resource constraints.

Despite these changes, fundamental principles established decades ago remain relevant. Memory protection, process scheduling, file systems, security models, and abstraction layers pioneered in the 1960s and 1970s still underpin modern systems. The Unix philosophy of composable tools and clear interfaces influences contemporary software design. The graphical interface innovations from Xerox PARC, Apple, and Microsoft define how billions of people interact with computers.

Understanding operating system history reveals that today’s systems did not emerge overnight but evolved through generations of innovation, each building on what came before while addressing new challenges. The smartphones in our pockets, the laptops on our desks, and the servers in data centers all inherit ideas from pioneers who grappled with computing challenges when computers filled rooms and cost fortunes. This continuity across decades shows both the lasting value of good ideas and the endless capacity for improvement as each generation refines what was inherited and adds capabilities enabled by advancing technology.