Introduction: The Silent Revolution in Your Pocket

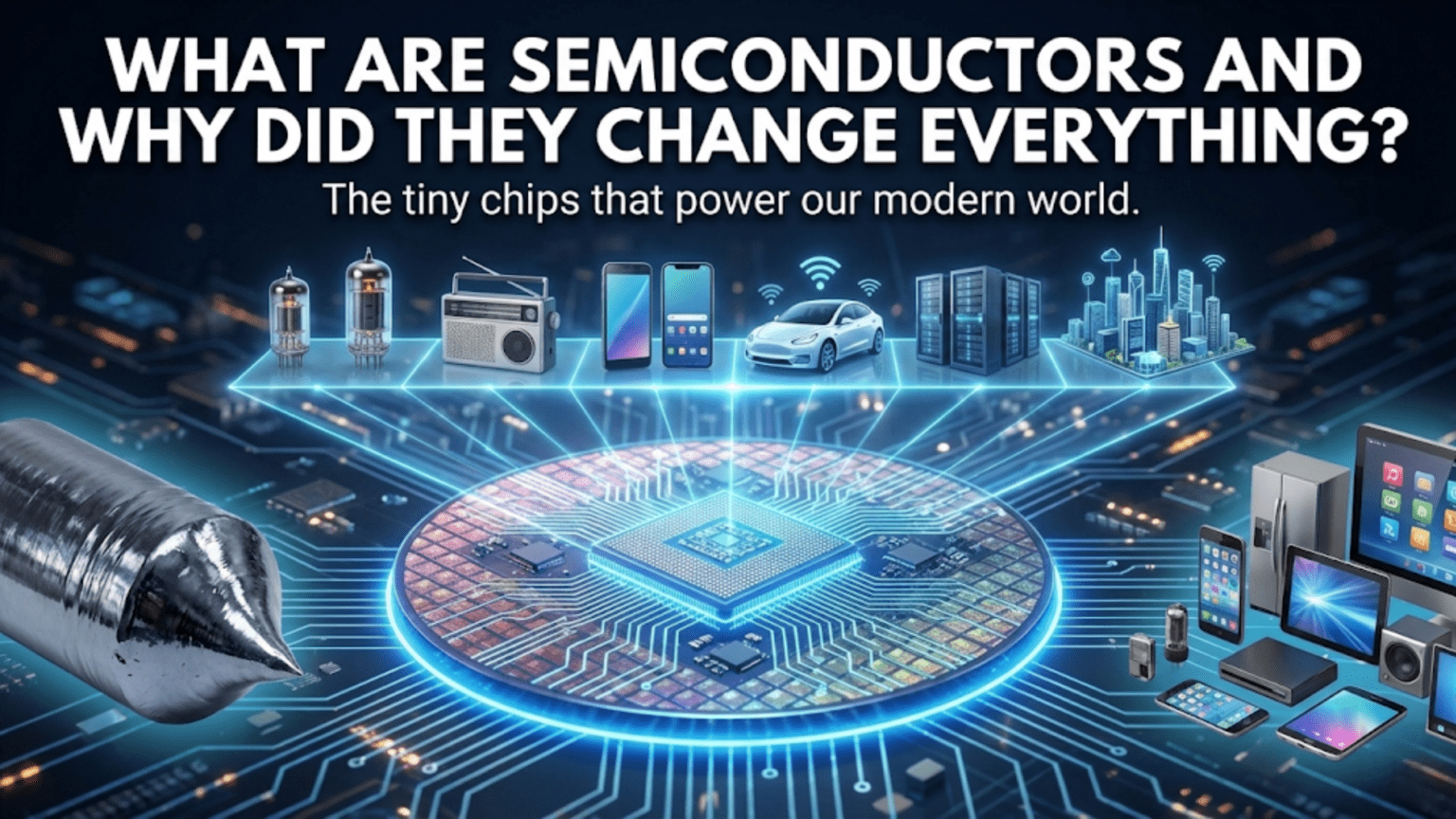

If you’re reading this on a smartphone, laptop, or tablet, you’re holding millions of semiconductors in your hand right now. In fact, semiconductors are so fundamental to modern life that without them, we’d be living in a world that looks remarkably like the 1940s. No computers, no smartphones, no internet, no modern medical equipment, and no space exploration. The semiconductor revolution didn’t arrive with fanfare like the steam engine or the airplane, but it has arguably transformed human civilization more profoundly than any other invention in history.

But what exactly is a semiconductor? The name itself seems contradictory. How can something be both a conductor and not a conductor at the same time? More importantly, what makes this mysterious property so incredibly useful that entire industries and trillions of dollars of economic value rest upon it?

In this comprehensive guide, we’re going to journey from the atomic structure of materials all the way to understanding why semiconductors became the foundation of the digital age. We’ll build your understanding step by step, starting with the fundamental concepts and gradually revealing how these seemingly simple materials enabled the most complex machines humanity has ever created. By the end, you’ll understand not just what semiconductors are, but why they represent one of the most important discoveries in human history.

Understanding Conductivity: The Foundation

Before we can understand semiconductors, we need to establish what we mean by electrical conductivity itself. This journey begins at the atomic level, where the behavior of tiny particles determines whether a material will conduct electricity freely, resist it completely, or do something fascinatingly in between.

How Materials Conduct Electricity

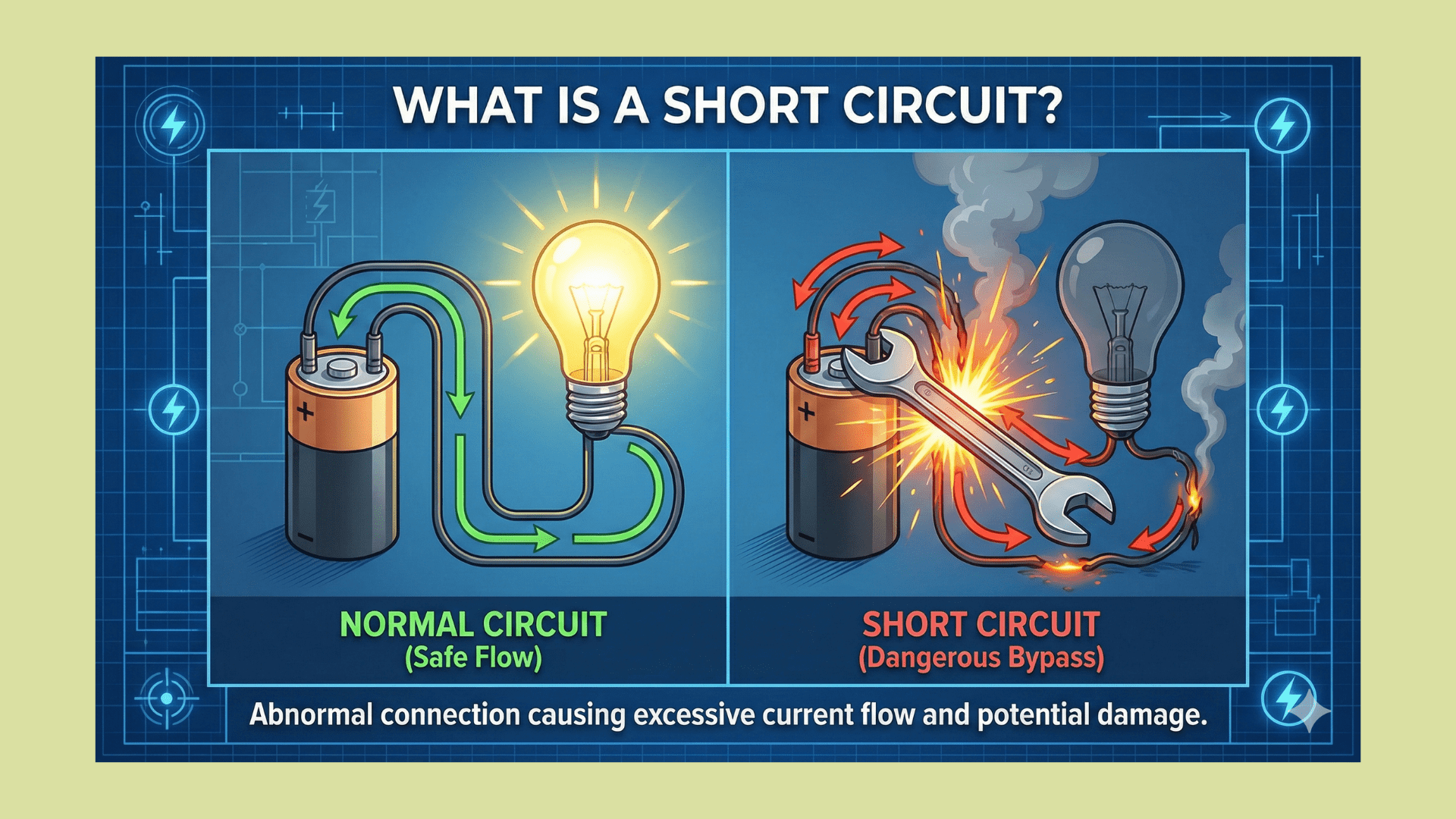

Electricity, at its most fundamental level, is the movement of electrons. When you flip a light switch, you’re creating a pathway that allows electrons to flow from your power source through the wires to the light bulb. But not all materials allow electrons to move through them with the same ease.

Think of electrons in a material like people in a crowded building. In some materials, the electrons are tightly bound to their parent atoms, like people locked in separate rooms. They can’t move around easily. In other materials, electrons are free to roam, like people in a building with no walls, able to flow wherever they need to go. This mobility of electrons determines whether a material conducts electricity.

In metals like copper or aluminum, the outermost electrons in each atom are very loosely bound. These electrons exist in what we call a “sea of electrons,” floating freely between atoms. When you apply a voltage across a piece of copper wire, these free electrons immediately respond to the electrical force and begin flowing in one direction. This is why metals are excellent conductors. They have an abundance of electrons that are already mobile and ready to move when an electrical force is applied.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we have insulators like rubber, glass, or plastic. In these materials, electrons are tightly bound to their parent atoms. The energy required to pull an electron away from its atom is very high. When you apply a voltage across an insulator, the electrons remain stubbornly attached to their atoms, refusing to flow. No current flows, and the material acts as a barrier to electricity. This is why we wrap copper wires in plastic insulation; the plastic prevents the electrons in the copper from escaping and causing short circuits.

The Resistivity Spectrum

If we were to line up all materials from best conductor to best insulator, we’d find they span an enormous range. Copper, one of the best conductors, has a resistivity of about 1.7 × 10⁻⁸ ohm-meters. Glass, a good insulator, has a resistivity around 10¹⁰ ohm-meters. That’s a difference of about 18 orders of magnitude, or a factor of one quintillion. To put this in perspective, if copper’s resistivity were one second, glass’s resistivity would be over 30 billion years, longer than the age of the universe.

For most of human history, we only recognized these two categories: conductors and insulators. Conductors were useful for moving electricity where we wanted it. Insulators were useful for preventing electricity from going where we didn’t want it. This binary understanding was sufficient for building electrical systems, motors, generators, and even the early electronic equipment like radio tubes. But it limited what we could do with electricity because we could only turn it on or off, send it or block it.

The existence of materials that fell between these two extremes, materials that conducted electricity but not as well as metals, had been known for many years. But these materials were considered curiosities, nuisances even, with no practical application. They were too conductive to be good insulators and too resistive to be good conductors. Why would anyone want something in between?

The answer to that question would change the world.

What Makes a Semiconductor Different?

A semiconductor is a material whose electrical conductivity falls between that of a conductor and an insulator. But this simple definition vastly understates what makes semiconductors special. The magic of semiconductors isn’t just that they’re medium conductors; it’s that their conductivity can be precisely controlled and modified in ways that conductors and insulators cannot.

The Atomic Structure of Semiconductors

To understand semiconductors, we need to look at their atomic structure. The most common semiconductor, and the one that powers most of modern electronics, is silicon. Let’s examine why silicon has such special properties.

Silicon sits in column 14 of the periodic table, which means each silicon atom has four electrons in its outermost shell. These are called valence electrons, and they’re the ones that participate in chemical bonding and electrical conduction. Here’s the crucial point: four is a significant number because it’s exactly half of what the outer shell “wants” to have to be full. A full outer shell would have eight electrons, which represents a very stable configuration.

Silicon atoms solve this problem through a process called covalent bonding. Each silicon atom shares its four valence electrons with four neighboring silicon atoms, and in return, it shares in their electrons. Through this mutual sharing, each atom effectively has access to eight electrons, creating a stable crystal structure. Imagine four friends, each with four apples, who agree to share their apples with each other so that everyone has access to eight apples total. This sharing creates strong bonds between them.

At absolute zero temperature (−273.15°C), this structure is perfect. Every electron is locked in a covalent bond, holding atoms together. There are no free electrons available to conduct electricity. Pure silicon at absolute zero would actually be an insulator.

But here’s where things get interesting. At room temperature, thermal energy is constantly jostling atoms around. Occasionally, this thermal energy is enough to break a covalent bond, freeing an electron from its position. When this happens, two things occur simultaneously. First, you get a free electron that can move through the crystal and conduct electricity. Second, you leave behind a “hole,” a missing electron in the covalent bond structure.

This hole isn’t just an absence; it’s a positive charge that can also move through the crystal. Think of it like a puzzle with one missing piece. You can move the empty space around by sliding the surrounding pieces into it. In a semiconductor, electrons from neighboring bonds can jump into the hole, but in doing so, they create a new hole where they came from. The hole effectively moves in the opposite direction to the electrons.

The Temperature Relationship

This creation of electron-hole pairs through thermal energy explains why semiconductors have a unique relationship with temperature. As temperature increases, more bonds are broken, more electron-hole pairs are created, and conductivity increases. This is the opposite of metals, where increasing temperature actually decreases conductivity because the vibrating atoms scatter electrons more, impeding their flow.

At room temperature, pure silicon has a small but measurable number of free electrons and holes, giving it a modest conductivity. This conductivity is far less than copper but far more than glass. However, this natural, thermally-generated conductivity isn’t what makes semiconductors useful. What makes semiconductors revolutionary is what we can do to them through a process called doping.

Doping: Engineering Electrical Properties

The transformative power of semiconductors comes from our ability to precisely control their electrical properties by adding tiny amounts of impurities. This process is called doping, and it’s one of the most important techniques in all of electronics.

N-Type Semiconductors: Adding Extra Electrons

Let’s return to our silicon crystal. Remember, each silicon atom has four valence electrons and forms four covalent bonds with its neighbors. Now imagine we replace one silicon atom out of every million with an atom of phosphorus.

Phosphorus sits in column 15 of the periodic table, meaning it has five valence electrons instead of four. When a phosphorus atom takes the place of a silicon atom in the crystal structure, four of its electrons participate in the regular covalent bonds with the four neighboring silicon atoms. But there’s one electron left over. This fifth electron is very loosely bound to the phosphorus atom because the crystal structure doesn’t need it.

At room temperature, this extra electron easily breaks free and becomes available for electrical conduction. We’ve essentially added a free electron to the semiconductor without needing to break any bonds. The phosphorus atom becomes a positively charged ion (since it lost an electron), but it’s locked in place in the crystal structure and can’t move.

We call phosphorus a donor atom because it donates an electron to the conduction process. A semiconductor doped with donor atoms is called an N-type semiconductor (N for negative, because we’ve added negatively charged electrons). In N-type material, electrons are the majority carriers; they’re the primary particles that carry current. There are also holes present from the normal thermal generation of electron-hole pairs, but they’re far outnumbered by the donated electrons from the dopant atoms.

The beautiful thing about this process is its precision. By controlling exactly how many phosphorus atoms we add, we can control exactly how conductive the material becomes. Add one phosphorus atom per billion silicon atoms, and you get one level of conductivity. Add one per million, and the conductivity increases by a factor of a thousand. We can tune the electrical properties with incredible precision.

P-Type Semiconductors: Creating Mobile Holes

Now let’s consider what happens if we dope silicon with an atom from column 13 of the periodic table, such as boron. Boron has only three valence electrons. When a boron atom replaces a silicon atom in the crystal, it forms three strong covalent bonds with three of its silicon neighbors. But the fourth neighboring silicon atom has an electron that wants to form a bond, but there’s no electron from the boron atom to bond with.

This creates a hole in the bonding structure. However, this hole can easily be filled by an electron from a neighboring silicon-silicon bond, which then creates a new hole in that bond. The hole can move through the crystal as electrons jump in to fill it, creating the appearance of a positive charge moving in the opposite direction.

We call boron an acceptor atom because it accepts an electron from the surrounding structure. A semiconductor doped with acceptor atoms is called P-type semiconductor (P for positive, because the holes act as positive charge carriers). In P-type material, holes are the majority carriers.

The Revolutionary Insight

Here’s the revolutionary insight that changed everything: by combining N-type and P-type semiconductors in various arrangements, we can create devices that control the flow of electricity in ways that were previously impossible. We can create switches with no moving parts that turn on and off millions of times per second. We can create amplifiers that take tiny signals and make them larger. We can create memory devices that store information as patterns of electrical charge.

The ability to precisely control where current flows, when it flows, and how much flows, all at microscopic scales, is what enabled the digital revolution. But to understand how this works, we need to explore what happens when you bring N-type and P-type semiconductors together.

The PN Junction: Where the Magic Happens

When you bring a piece of P-type semiconductor into contact with a piece of N-type semiconductor, something fascinating happens at the boundary between them. This junction is the foundation of nearly every semiconductor device, so understanding it is crucial to understanding why semiconductors changed everything.

The Depletion Region Forms

Imagine the moment when P-type and N-type materials are brought into contact. On the P-type side, you have an abundance of holes (and negatively charged acceptor ions fixed in the crystal). On the N-type side, you have an abundance of free electrons (and positively charged donor ions fixed in the crystal).

Nature abhors such imbalances. The free electrons from the N-type material, which are in constant thermal motion, diffuse across the junction into the P-type material. Similarly, holes from the P-type material diffuse into the N-type material. When an electron crosses into the P-type side, it quickly finds a hole and fills it, and both the electron and hole disappear. This is called recombination.

But here’s what’s crucial: when electrons leave the N-type material, they leave behind positively charged donor ions. When holes leave the P-type material (which really means electrons are flowing in), negatively charged acceptor ions are left behind. These ions are fixed in the crystal structure and can’t move.

This creates a region right at the junction that is depleted of mobile charge carriers. On the N-type side of this depletion region, there are positive ions. On the P-type side, there are negative ions. This separation of positive and negative charges creates an electric field pointing from the N-type side to the P-type side.

This electric field is crucial. It acts as a barrier that prevents further diffusion of electrons and holes across the junction. An electron trying to diffuse from N-type to P-type has to work against this electric field, like trying to roll a ball uphill. Eventually, an equilibrium is reached where the tendency of electrons and holes to diffuse is exactly balanced by the electric field pushing them back.

Forward Bias: Opening the Gate

Now here’s where we can start to control current flow. If we connect the positive terminal of a battery to the P-type side and the negative terminal to the N-type side, we create what’s called a forward bias condition.

The external voltage from the battery opposes the internal electric field in the depletion region. If we make the external voltage large enough, it can overcome the barrier created by the internal field. When this happens, electrons from the N-type material can easily flow across the junction into the P-type material, and holes from the P-type material can flow into the N-type material.

Current flows freely through the junction. The device offers very low resistance. We’ve essentially opened a gate and allowed electricity to flow.

Reverse Bias: Closing the Gate

What if we reverse the battery connection, putting the positive terminal on the N-type side and the negative terminal on the P-type side? This is called reverse bias.

Now the external voltage reinforces the internal electric field. The barrier to current flow becomes even larger. Electrons are pulled away from the junction on the N-type side, and holes are pulled away on the P-type side. The depletion region actually widens. No current flows (or more precisely, only a tiny leakage current flows).

We’ve closed the gate. The device now has very high resistance.

The Diode: A One-Way Valve for Electricity

This PN junction, with its ability to conduct electricity easily in one direction (forward bias) but block it in the other direction (reverse bias), is called a diode. The diode is the simplest semiconductor device, but it’s incredibly useful. It acts like a one-way valve for electricity.

But the diode is just the beginning. The real power of semiconductors emerges when we create more complex structures with multiple junctions. This leads us to the device that truly changed everything: the transistor.

The Transistor: The Device That Changed the World

If the diode is a valve that current can only flow through in one direction, the transistor is a valve where a small control current can turn a larger current on and off, or amplify a small signal into a larger one. To understand why this is revolutionary, we need to see what it replaced.

Before Transistors: The Vacuum Tube Era

Before transistors, electronic amplification and switching were performed by vacuum tubes. These glass bottles contained a heated cathode that emitted electrons, an anode that collected them, and one or more grids in between that controlled the flow. By varying the voltage on the grid, you could control how many electrons flowed from cathode to anode, achieving amplification or switching.

Vacuum tubes worked, and they enabled the early computer age and the golden age of radio and television. But they had serious problems. They were large, typically several inches in size. They consumed significant power, mostly wasted as heat from the filament that heated the cathode. They were fragile, burning out frequently like light bulbs. And they were expensive to manufacture.

The first electronic computer, ENIAC, built in 1945, used about 18,000 vacuum tubes. It occupied 1,800 square feet, weighed 30 tons, and consumed 150 kilowatts of power. It also generated so much heat that it required a dedicated cooling system, and tube failures were so common that the machine was down for maintenance much of the time.

Imagine trying to build a smartphone with vacuum tubes. It’s not just impractical; it’s physically impossible. The device would be the size of a room, require its own power plant, and even then couldn’t perform a tiny fraction of what a modern smartphone does.

The Birth of the Transistor

In 1947, at Bell Telephone Laboratories, three researchers named John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley created the first working transistor. Their initial point-contact transistor was crude and unreliable, but it demonstrated that solid-state materials could perform the same amplification and switching functions as vacuum tubes, without the heat, power consumption, or fragility.

The following year, Shockley invented the junction transistor, which had a more practical structure. The most common type, the bipolar junction transistor (BJT), consists of three layers of doped semiconductor: either NPN (N-type, P-type, N-type) or PNP (P-type, N-type, P-type).

How a Transistor Works: The NPN Example

Let’s understand an NPN transistor, which consists of a thin P-type layer sandwiched between two N-type layers. The three layers are called the emitter (first N), base (P), and collector (second N).

In normal operation, the junction between the emitter and base is forward biased, meaning we apply a voltage that allows current to flow from the emitter into the base. However, the base is made very thin and lightly doped. Most of the electrons that enter the base from the emitter don’t recombine with holes there because there aren’t many holes, and the base is so thin. Instead, they are swept across into the collector by the electric field from the collector-base junction, which is reverse biased.

Here’s the key insight: a small current flowing into the base controls a much larger current flowing from the emitter to the collector. If you increase the base current slightly, you increase the collector current substantially. If you cut off the base current, the collector current stops entirely.

This is amplification. A small input signal at the base appears as a much larger output signal at the collector. Or thinking of it as a switch, a small base current acts like a control signal that turns a larger collector current on and off.

Why This Was Revolutionary

The transistor offered everything the vacuum tube could do, but with transformative advantages. It was solid-state, with no moving parts and no heated filaments to burn out. It was tiny, potentially much smaller than any vacuum tube. It consumed very little power. It was durable and could last essentially forever. And crucially, it could be manufactured using the techniques of chemical processing, which meant costs would drop dramatically with mass production.

But perhaps the most important advantage wasn’t immediately obvious in 1947. Transistors could be made smaller and smaller, and multiple transistors could potentially be built on the same piece of semiconductor material. This led to the integrated circuit and eventually to modern microprocessors.

From Transistors to Integrated Circuits

A single transistor was useful, but the real power of semiconductors emerged when engineers figured out how to build many components on a single piece of semiconductor material. This created the integrated circuit, or IC.

The Problem of Interconnections

In the 1950s, as electronic systems became more complex, the number of transistors and other components grew rapidly. These components had to be individually manufactured, then connected together with wires soldered by hand. The process was labor-intensive, expensive, and error-prone.

More fundamentally, there was a looming crisis. As systems required more and more components, the reliability of the overall system decreased. If each component has a 99.9% reliability, a system with 1,000 components has an overall reliability of only about 37%. The interconnections between components were also failure points. Engineers realized that to build truly complex electronic systems, they needed a fundamentally different approach.

The Planar Process and Photolithography

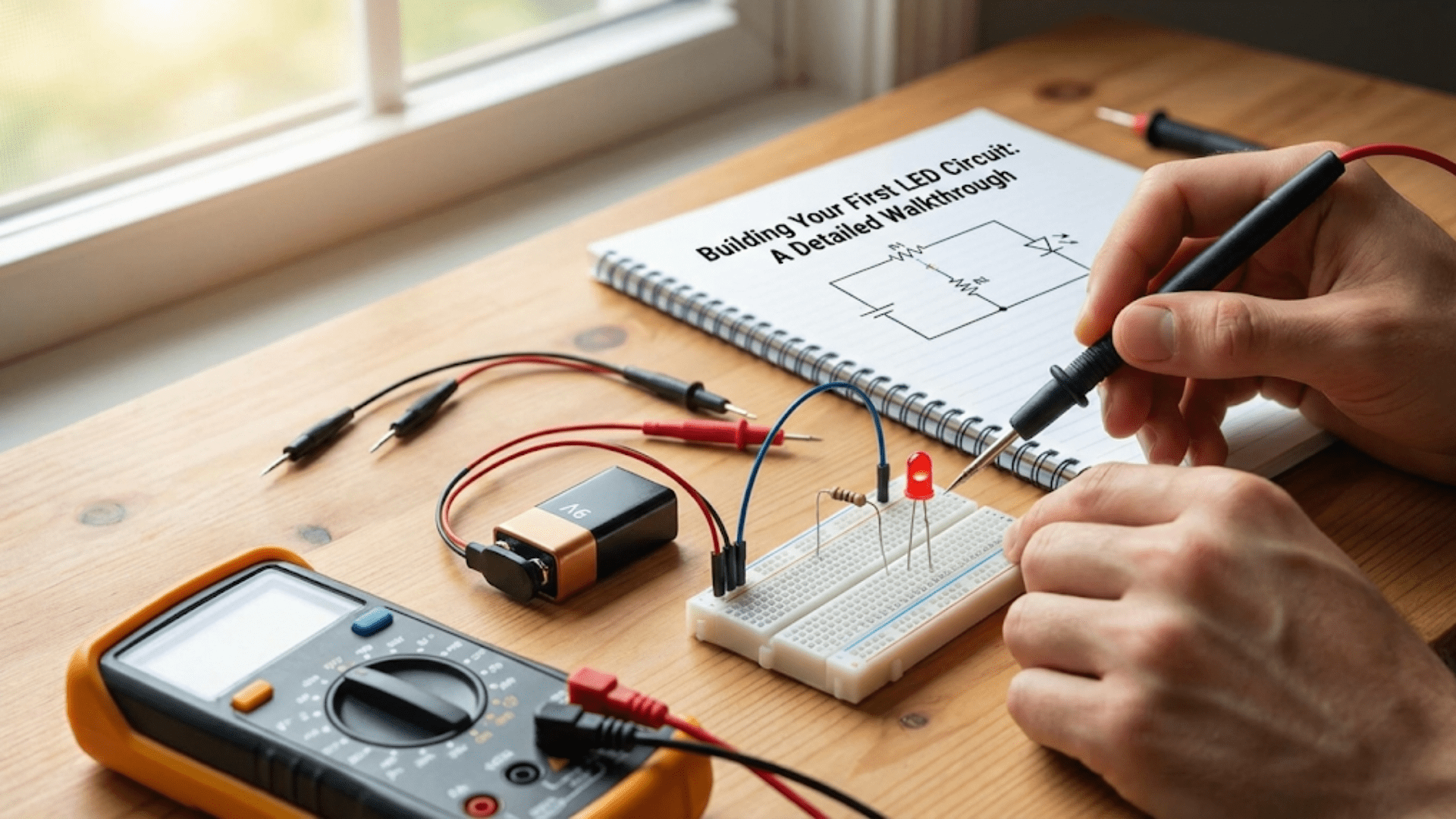

The breakthrough came from two key innovations. First, in 1959, Jean Hoerni at Fairchild Semiconductor developed the planar process, a way of manufacturing transistors where all the junctions are created by diffusing dopants into a flat surface of silicon. This made transistors much more reliable and manufacturable.

Second, engineers adapted techniques from the printing industry to create photolithography. This process works like a photographic negative. You coat the silicon surface with a light-sensitive material, shine ultraviolet light through a mask that has the pattern of your circuit, and the exposed areas become either more or less soluble in chemical developers. After development, you’re left with a pattern on the silicon surface that protects some areas while leaving others exposed. You can then add or remove material in the exposed areas, creating the structures you need for transistors, wires, and other components.

The genius of photolithography is that making one transistor or one thousand transistors is essentially the same process. You create a mask with the pattern for all your components and wires, and in one photographic step, you transfer that pattern to the silicon. The complexity of the circuit doesn’t significantly affect manufacturing cost or difficulty.

The Integrated Circuit Is Born

In 1958, Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments demonstrated the first integrated circuit, a simple device with a few components built on a single piece of semiconductor. A few months later, Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor invented a more practical version using the planar process. These inventors showed that you could build transistors, resistors, capacitors, and the connections between them all on one chip.

The advantages were enormous. The circuit was smaller, more reliable (no hand-soldered connections to fail), consumed less power, and cost less to manufacture in volume. Most importantly, the photolithographic process meant that more complex circuits didn’t cost proportionally more. The development cost was higher, but the manufacturing cost per chip stayed nearly constant regardless of complexity.

This set the stage for the exponential growth that became known as Moore’s Law.

Moore’s Law and the Semiconductor Revolution

In 1965, Gordon Moore, one of the founders of Intel, made an observation that became a prediction and then became a self-fulfilling prophecy that guided the semiconductor industry for over five decades.

The Original Observation

Moore noticed that the number of transistors that could be economically placed on an integrated circuit was doubling approximately every year. He predicted this trend would continue for at least another decade. In 1975, he revised the prediction to doubling every two years, which has proven remarkably accurate.

This exponential growth might not seem impressive at first. Doubling every two years sounds modest. But exponential growth is deceptively powerful. If you start with 2,000 transistors per chip in 1970, doubling every two years gives you 4,000 in 1972, 8,000 in 1974, 16,000 in 1976, and so on. By the year 2000, you’d have over a billion transistors. By 2020, over 50 billion transistors on a single chip.

That’s exactly what happened. The first microprocessor, the Intel 4004 released in 1971, had 2,300 transistors. The Intel Pentium from 1993 had 3.1 million. The Intel Core i7 from 2008 had 731 million. Modern processors in 2025 have tens of billions of transistors.

Why Smaller Is Better

The semiconductor industry has relentlessly pursued smaller and smaller transistor sizes. This wasn’t just to fit more transistors on a chip, although that was important. Smaller transistors have multiple advantages.

First, smaller transistors switch faster. The time it takes for a signal to propagate through a transistor decreases as the physical size decreases. This means the processor can run at higher clock speeds.

Second, smaller transistors consume less power. The energy required to switch a transistor from off to on decreases with size. This is crucial for battery-powered devices and for managing heat in high-performance processors.

Third, smaller transistors are cheaper per transistor. If you can fit twice as many transistors in the same area of silicon, and your manufacturing cost is proportional to silicon area, then you’ve cut the cost per transistor in half.

These advantages created a virtuous cycle. Smaller transistors enabled faster, more power-efficient, cheaper chips. These chips enabled new applications, which drove demand for even better chips. The economic incentive to keep shrinking transistors was enormous, leading to investments of billions of dollars in each new generation of manufacturing technology.

From Microns to Nanometers

In the early 1970s, transistor feature sizes were measured in tens of microns (a micron is one millionth of a meter). By the 1990s, we reached the one-micron milestone. By 2000, we were at 130 nanometers (a nanometer is one billionth of a meter). By 2010, we reached 32 nanometers. As of 2025, the most advanced chips use transistors with features as small as 3 nanometers.

To put this in perspective, a human hair is about 75,000 nanometers in diameter. Modern transistors are so small that if you scaled a transistor up to the size of a marble, a marble would be the size of the Earth. At this scale, we’re dealing with structures just a few dozen atoms across.

This miniaturization has enabled computing devices to become ubiquitous. The smartphone in your pocket has more computing power than the supercomputers of the 1990s, uses less power, and costs a tiny fraction of what those supercomputers cost.

The Economics of Semiconductors

The semiconductor industry operates under unique economic principles that have shaped how technology develops and how companies compete.

High Fixed Costs, Low Marginal Costs

Building a modern semiconductor fabrication facility (called a fab) costs anywhere from 10 to 20 billion dollars. The equipment required for photolithography, chemical processing, and testing is extraordinarily expensive and complex. Developing a new chip design can cost hundreds of millions of dollars in engineering time and computer simulation.

However, once the fab is built and the design is complete, manufacturing additional chips is relatively cheap. The materials cost for a chip is just a few dollars. Most of the cost is in the fabrication process itself, which processes hundreds of chips simultaneously on large silicon wafers.

This economic model creates a powerful incentive to maximize production volume. The more chips you produce, the lower the per-chip cost becomes as you spread the fixed costs over more units. This has led to the semiconductor industry’s characteristic boom-and-bust cycles, as companies build expensive fabs in anticipation of demand, sometimes overbuilding and sometimes underbuilding capacity.

The Ecosystem Effect

As semiconductors became more powerful and cheaper, they enabled new applications that created demand for even more semiconductors. Personal computers created demand for microprocessors. Those computers enabled the internet, which created demand for networking chips and servers. Smartphones combined computing, networking, and cameras, creating demand for specialized processors, image sensors, and power management chips.

Each new application created a market for specialized semiconductor devices. This broad ecosystem means that investment in semiconductor technology benefits many industries simultaneously, creating a multiplier effect on the economy.

Winner-Take-Most Markets

The high fixed costs and low marginal costs create winner-take-most dynamics in semiconductor markets. The company that can achieve the highest volume can spread its fixed costs over the most chips, giving it the lowest per-unit cost. This allows it to either undercut competitors on price or invest more in the next generation of technology.

This dynamic has led to consolidation in the semiconductor industry. Many markets are dominated by just two or three major players who have the resources to compete at the cutting edge. Intel and AMD in microprocessors, Samsung and TSMC in manufacturing, Nvidia in graphics processors, and Qualcomm in mobile processors exemplify this pattern.

The Broader Impact: How Semiconductors Changed Everything

To truly appreciate why semiconductors changed everything, we need to look at the cascading effects they had across society.

The Digital Revolution

Semiconductors made digital computers practical, affordable, and eventually ubiquitous. The first computers were massive, expensive machines used only by governments and large corporations for specific calculations. Semiconductors enabled the minicomputer, then the personal computer, then the laptop, then the smartphone.

Each generation brought computing to more people and enabled new uses. Personal computers transformed how we work, write, and create. The internet, enabled by networking chips and the computers to connect to it, transformed how we communicate and access information. Smartphones put a powerful computer in everyone’s pocket, always connected, always accessible.

This digital revolution has fundamentally altered almost every human activity. Education, medicine, commerce, entertainment, communication, manufacturing, transportation, scientific research – all have been transformed by digital technology, which rests entirely on the foundation of semiconductor devices.

Communications Revolution

Semiconductors didn’t just enable computers; they revolutionized communications. The transistor made portable radios possible. Integrated circuits enabled the digital telephone network. Semiconductor lasers enabled fiber optic communications. Wireless communications depend on semiconductor transmitters and receivers.

The ability to communicate instantly with anyone, anywhere in the world, to access nearly all human knowledge from a device in your pocket, to share ideas and information at zero marginal cost – none of this would exist without semiconductors. These changes have had profound social and political implications, democratizing information and enabling new forms of organization and collective action.

Medical Advances

Modern medicine depends heavily on semiconductor devices. Medical imaging equipment like MRI scanners, CT scanners, and ultrasound machines all rely on sophisticated semiconductor-based signal processing. DNA sequencing, which has transformed genetics and is enabling personalized medicine, uses semiconductor-based detection methods.

Portable medical devices like glucose monitors, heart rate monitors, and even pacemakers rely on low-power semiconductor circuits. The ability to monitor health continuously and intervene early has saved countless lives. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the critical importance of semiconductor-enabled medical devices and the digital infrastructure for tracking and responding to health crises.

Scientific Discovery

Semiconductors have accelerated scientific progress across all fields. Advanced simulations of everything from protein folding to climate systems to galaxy formation require enormous computational power. Modern experiments generate vast amounts of data that must be processed and analyzed with sophisticated algorithms.

Semiconductor-based sensors enable us to detect phenomena we could never observe before, from gravitational waves to individual photons. The instruments on spacecraft exploring our solar system and beyond are all based on semiconductor technology. The Large Hadron Collider uses semiconductor detectors and requires massive computing power to analyze the collision data.

In a real sense, our ability to understand the universe is now limited more by the availability of computing power than by pure theoretical capability, making semiconductors essential to the scientific enterprise.

Energy and Environment

Semiconductors play a crucial role in addressing energy and environmental challenges. Solar panels, which convert sunlight directly into electricity, are based on semiconductor physics. Power electronics using semiconductor switches enable efficient conversion and control of electrical power, reducing waste in everything from industrial motors to electric vehicle drivetrains.

Smart grids that can balance variable renewable energy sources, electric vehicles that can replace fossil fuel transportation, and energy-efficient appliances that reduce consumption all depend on semiconductor technology. While semiconductors consume energy in their operation, particularly in data centers, they enable energy savings throughout the economy that far exceed their own consumption.

Economic Transformation

The semiconductor industry itself is worth hundreds of billions of dollars annually, but its economic impact is far larger. The industries enabled by semiconductors – computers, telecommunications, consumer electronics, automotive electronics, industrial automation, and more – represent trillions of dollars in economic activity.

Semiconductors have also enabled entirely new business models. Software-as-a-service, e-commerce, the sharing economy, social media platforms, and countless other innovations depend on cheap, ubiquitous computing power. These new models have created enormous economic value and have disrupted traditional industries.

The productivity improvements enabled by digital technology, all based on semiconductors, are difficult to fully quantify but are undoubtedly substantial. Automation of manufacturing, optimization of logistics, efficiency of communications, and accessibility of information all contribute to economic growth.

The Physics Becomes the Limit: Modern Challenges

As transistors have shrunk to just a few nanometers, the semiconductor industry faces fundamental challenges rooted in the physics of matter at atomic scales.

Quantum Effects

At the scale of modern transistors, quantum mechanical effects become significant. Electrons can tunnel through barriers they classically shouldn’t be able to cross, causing leakage current. The position and momentum of electrons become uncertain. The discrete nature of electric charge becomes important when there are only a few dozen electrons controlling a transistor’s state.

Engineers have developed clever techniques to manage these effects, such as using new materials, creating three-dimensional transistor structures (FinFETs and gate-all-around FETs), and accepting that some leakage current is unavoidable. But these techniques add complexity and cost to manufacturing.

Heat Density

As transistors have shrunk and clock speeds have increased, the power density in processors has increased dramatically. Modern high-performance processors can dissipate over 100 watts in an area smaller than a postage stamp. Removing this heat is a major engineering challenge.

Clock speeds have largely plateaued since the mid-2000s because increasing them further would create unmanageable heat. Instead, performance improvements now come from having more processors running in parallel (multi-core processors) and from architectural improvements that do more work per clock cycle.

Manufacturing Complexity

Creating features just a few nanometers across requires manufacturing precision that pushes the limits of what’s physically possible. The photolithography process now uses extreme ultraviolet (EUV) light with a wavelength of just 13.5 nanometers. The mirrors and optical systems for EUV lithography are among the most precise objects ever manufactured, flat to within a fraction of a nanometer over areas of tens of centimeters.

The cost and complexity of manufacturing have increased dramatically. There are now only a handful of companies in the world capable of producing the most advanced chips, and the equipment manufacturers who supply them are highly specialized monopolies or duopolies. The knowledge required spans physics, chemistry, materials science, optics, mechanical engineering, and computer science at the highest levels.

The Question of Limits

We’re approaching fundamental limits on how small transistors can be made. At some point, we’ll reach the size where a transistor is just a few atoms across, and the discrete nature of matter makes further scaling impossible. Many experts believe we’ll reach these limits within the next decade or two.

This doesn’t mean progress will stop. There are many ways to continue improving computing beyond pure transistor scaling. Three-dimensional stacking of circuits, new computing architectures like neuromorphic processors that mimic the brain, quantum computers for specific applications, and photonic circuits that use light instead of electrons all offer paths forward. But the era of exponential improvement through simple shrinking is approaching its end.

Conclusion: A Foundation for the Future

Semiconductors changed everything because they gave humanity precise control over the flow of electricity at microscopic scales. This control enabled digital computing, which in turn enabled the information revolution that has transformed every aspect of modern life.

The journey from the discovery that certain materials have controllable conductivity to modern processors with tens of billions of transistors is one of the most remarkable achievements in human history. It required insights from fundamental physics, innovations in chemistry and materials science, engineering at the limits of physical possibility, and economic organization on a global scale.

For anyone learning electronics today, understanding semiconductors is essential not just for technical reasons, but for understanding the foundation of the modern world. Every digital device you use, every internet connection you make, every photo you take, every video you watch, every calculation performed on your behalf – all of it depends on the special properties of semiconductor materials.

As we face the physical limits of semiconductor scaling, new challenges and opportunities emerge. The fundamental principles remain the same – controlling electrical current with precision – but the implementations will evolve. Whether through new materials like graphene, new device structures, new computing paradigms, or combinations of technologies, the quest to build better computing devices will continue.

The semiconductor revolution is not over; it’s entering a new phase. Understanding where we’ve been helps us appreciate where we’re going. For beginners in electronics, these semiconductor principles are your foundation for understanding not just how individual components work, but how the entire technological landscape of the 21st century came to be.

The most exciting part? Every day, researchers and engineers around the world are pushing these boundaries further, finding new ways to harness the unique properties of semiconductor materials. The discoveries that will enable the next revolution might be happening in a laboratory right now, waiting to change everything once again. That’s the enduring promise and power of semiconductors – materials that gave us control over electricity, which gave us control over information, which continues to transform what’s possible for humanity.