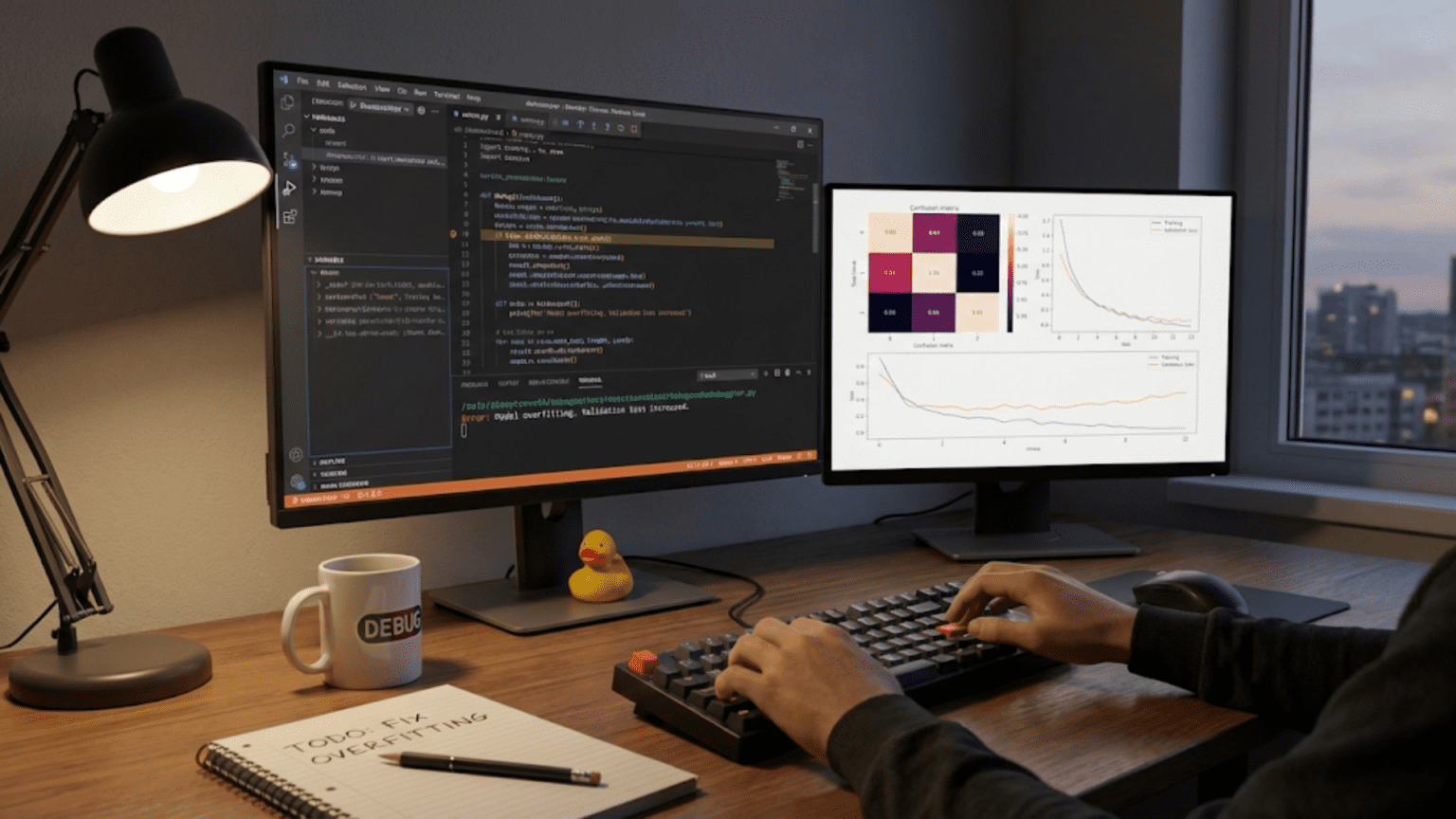

Imagine you are a detective investigating a complex case where a valuable artifact has gone missing from a museum. You arrive at the scene to find dozens of potential suspects, hundreds of pieces of evidence, and conflicting witness testimonies. Simply looking at this overwhelming mass of information does not immediately reveal what happened. Instead, you must systematically narrow down possibilities by forming hypotheses about what might have occurred, then testing each hypothesis against the evidence. You might hypothesize that the thief entered through a specific door, then check security footage to confirm or refute that theory. You eliminate suspects by verifying their alibis. You trace the artifact’s movements by examining records and interviewing staff. When you encounter contradictions or impossibilities, you backtrack and reconsider your assumptions. Through this methodical process of hypothesis formation, evidence gathering, logical deduction, and iterative refinement, you gradually piece together what actually happened from the confusing mass of initial information. This investigative process mirrors precisely what programmers do when debugging code, particularly the complex and often opaque code involved in machine learning. When your model produces unexpected results, crashes with cryptic errors, or silently fails by learning nothing useful from data, you must become a detective investigating what went wrong in the intricate chain of operations from data loading through preprocessing to training and evaluation.

Machine learning code presents unique debugging challenges that distinguish it from debugging traditional software. In conventional programming, bugs typically produce clear errors or obviously wrong outputs. If your accounting software calculates that two plus two equals five, you immediately know something is wrong. In machine learning, bugs often manifest as models that run successfully and produce plausible but incorrect outputs. A model might achieve seventy percent accuracy when it should achieve ninety percent, or it might work well on training data but fail on test data, or it might make predictions that seem reasonable individually but contain systematic biases. These subtle failures do not crash your program or produce error messages, making them much harder to detect and diagnose than traditional bugs. You must develop new debugging strategies beyond the standard approaches used for deterministic software.

The complexity of machine learning systems compounds debugging difficulty. A typical machine learning pipeline involves dozens of steps including data loading from files or databases, data validation to check for quality issues, feature extraction that transforms raw data into model inputs, missing value imputation, feature scaling, data augmentation, model initialization, training loops that adjust parameters, prediction generation, and result post-processing. Bugs can occur in any of these steps, and problems in early steps often create misleading symptoms in later steps. If your feature scaling is subtly incorrect, your model might appear to train normally but achieve poor test performance. If your data loading introduces subtle corruption, the entire pipeline fails despite each individual component working correctly in isolation. Debugging requires understanding the full pipeline and how components interact rather than just examining individual pieces.

The probabilistic and numerical nature of machine learning adds another debugging dimension. Machine learning involves random sampling, stochastic optimization, floating-point arithmetic, and mathematical operations that can encounter numerical instability. A model’s behavior might change each time you run it due to random seed differences. Gradients might explode or vanish during training due to poor initialization or inappropriate learning rates. Matrix operations might produce NaN or infinity values from subtle numerical issues. These behaviors are normal aspects of numerical computing that you must learn to anticipate and handle rather than bugs to eliminate. Distinguishing between expected numerical variability and genuine bugs requires understanding machine learning’s mathematical foundations.

Yet despite these challenges, debugging machine learning code is a learnable skill built on systematic approaches, good development practices, and accumulated experience recognizing common failure patterns. Professional machine learning engineers are not superhuman debuggers with mysterious abilities to divine bug locations. Instead, they follow disciplined processes, use appropriate tools, write tests that catch problems early, add validation checks throughout pipelines, visualize intermediate results, and build intuition from previous debugging experiences about where to look for different types of problems. Learning these systematic debugging approaches transforms debugging from frustrated trial-and-error into a methodical process that efficiently isolates and fixes problems. Combining debugging skills with testing practices that prevent bugs from occurring in the first place dramatically improves code quality and development productivity.

In this comprehensive guide, we will build your machine learning debugging and testing skills from fundamental concepts through advanced techniques used in production systems. We will start by understanding the unique characteristics of machine learning bugs and why they differ from traditional software bugs. We will learn systematic debugging processes for isolating problems efficiently when they occur. We will explore common bug categories in machine learning including data problems, preprocessing errors, model configuration mistakes, training issues, and evaluation pitfalls. We will understand how to use Python debugging tools including print statements, debuggers, and logging effectively for machine learning code. We will learn to add assertions and validation checks throughout code to catch problems early. We will explore strategies for debugging specific machine learning components including data loaders, preprocessing pipelines, model architectures, and training loops. We will understand testing practices including unit tests, integration tests, and data validation tests that prevent bugs before they cause problems. We will learn to create reproducible environments that eliminate non-deterministic bugs from randomness. We will explore visualization techniques that reveal problems invisible to numerical inspection. Throughout, we will use concrete examples from real machine learning debugging scenarios, and we will build the systematic thinking that enables you to debug confidently rather than panic when code does not work as expected. By the end, you will have both the conceptual understanding of effective debugging and the practical techniques to find and fix problems efficiently in your own machine learning projects.

Understanding Machine Learning Bugs

Before diving into debugging techniques, understanding what kinds of bugs afflict machine learning code and why they differ from traditional software bugs provides essential context for effective debugging strategies.

The Unique Nature of Machine Learning Bugs

Traditional software bugs typically produce deterministic failures. If a sorting algorithm has a bug, it consistently produces wrong output for specific input patterns. You can reproduce the bug reliably, test a proposed fix, and verify the fix worked. Machine learning bugs often behave differently. A model training bug might cause the loss to fluctuate randomly rather than decrease smoothly, or it might cause the model to work well on some random seeds but fail on others, or it might produce slightly worse performance that you might initially attribute to inherent randomness rather than a bug.

This non-determinism makes machine learning bugs harder to isolate. You cannot simply rerun code and expect identical behavior because random initialization, data shuffling, and stochastic optimization mean results vary between runs. Distinguishing genuine bugs from normal random variation requires statistical thinking and multiple runs to observe patterns. A training loss that occasionally increases does not necessarily indicate a bug because stochastic gradient descent naturally has noisy updates. But a loss that never decreases or that increases steadily does indicate a problem.

Silent failures are particularly insidious in machine learning. Code that successfully runs to completion might contain serious bugs that manifest only as poor performance rather than errors or crashes. If you accidentally train on your test data, creating data leakage, your code runs perfectly but your evaluation is worthless. If you apply transformations in the wrong order, your code still produces predictions but they are based on corrupted features. If you initialize your model poorly, training might simply take much longer to converge or might converge to a worse solution than possible, without any error message indicating the problem. Detecting these silent failures requires understanding what good performance looks like and recognizing when results seem suspicious.

The high-dimensional nature of machine learning data and models creates another debugging challenge. When your input data has hundreds of features and your model has millions of parameters, you cannot simply look at all values to spot problems. A single corrupted feature in a dataset with hundreds of features might be nearly invisible in summary statistics but could substantially degrade model performance. Understanding which features or parameters are problematic requires targeted investigation guided by hypotheses about what might be wrong rather than exhaustive inspection of every value.

Common Categories of Machine Learning Bugs

Machine learning bugs cluster into several common categories that appear repeatedly across projects. Understanding these categories helps you recognize symptoms and know where to look when you suspect problems. Data bugs involve problems with how data is loaded, represented, or transformed. Examples include missing values encoded incorrectly, features scaled inappropriately, categorical variables not encoded properly, data leakage where test information influences training, and data shuffling not occurring properly. These data bugs often manifest as models that appear to train but achieve poor test performance or as training that seems abnormally easy or difficult.

Preprocessing bugs occur when transformations intended to prepare data for modeling are implemented incorrectly. Fitting preprocessing transformations on test data rather than just training data creates leakage. Applying transformations in the wrong order can corrupt data. Forgetting to apply transformations to test data that were applied to training data creates train-test distribution mismatch. These bugs typically manifest as good training performance but poor test performance, or as test performance that seems artificially good because of leakage.

Model architecture and configuration bugs involve mistakes in how models are structured or parameterized. Using activation functions inappropriately, connecting layers incorrectly in neural networks, specifying wrong input or output dimensions, or choosing hyperparameters that prevent learning all create model bugs. These often manifest as models that fail to train at all, producing constant losses or NaN values, or as models that train but achieve much worse performance than expected.

Training loop bugs affect how optimization occurs. Implementing gradient updates incorrectly, using wrong loss functions, failing to zero gradients between batches, or updating the wrong parameters all corrupt training. These bugs might cause training loss to not decrease, to increase, to oscillate wildly, or to decrease much slower than expected. Sometimes training appears to work but the trained model performs poorly because the optimization was fundamentally broken.

Evaluation bugs involve computing metrics or generating predictions incorrectly. Using wrong metrics, comparing predictions to wrong targets, not preprocessing evaluation data consistently with training data, or computing metrics only on subsets of data all corrupt evaluation. These bugs make you believe your model works better or worse than it actually does, leading to incorrect decisions about model selection and deployment.

Understanding these bug categories helps you form focused hypotheses when debugging. If your model achieves unrealistically good test performance, you should suspect data leakage. If training loss does not decrease, you should suspect model configuration or training loop bugs. If test performance is much worse than training performance, you should suspect preprocessing inconsistencies or evaluation bugs. This categorical thinking guides debugging much more efficiently than random exploration.

The Debugging Mindset

Effective debugging requires a specific mindset that differs from the mindset productive during development. When developing, you think expansively about what features to add and how to implement them. When debugging, you must think reductively about what could cause observed symptoms and how to test those hypotheses. Development is about building; debugging is about systematic elimination of possibilities.

The key debugging principle is to form specific, testable hypotheses about what might be wrong, then design tests that confirm or refute each hypothesis. Vague notions like “something is wrong with training” do not help. Specific hypotheses like “gradients are exploding due to large initial weights” or “the learning rate is too high for stable training” point toward concrete things to check. Each hypothesis suggests specific evidence to examine. If you suspect gradient explosion, you check gradient magnitudes during training. If you suspect learning rate issues, you try smaller learning rates and see if training stabilizes.

Good debugging also requires accepting when your hypotheses are wrong and moving to new ones rather than trying to force evidence to fit your favorite theory. If you are convinced the bug is in your data loading but adding detailed logging shows data loads correctly, you must abandon that hypothesis and look elsewhere rather than persisting because you were certain. This intellectual honesty about being wrong enables efficient debugging by preventing you from wasting time investigating dead ends.

Patience is crucial in debugging. Unlike development where you can see progress through new features appearing, debugging often involves eliminating possibilities one by one without obvious progress toward a solution. You might spend an hour ruling out data problems, another hour ruling out preprocessing problems, and finally find the issue in model configuration only after eliminating other possibilities. This process feels frustrating but is actually efficient because systematic elimination narrows the search space and eventually finds the bug. Panic and random changes waste time without progressing toward a solution.

Systematic Debugging Processes

Rather than randomly changing code hoping to fix bugs, following systematic processes finds bugs more reliably and efficiently. These processes structure your debugging efforts to maximize progress while minimizing wasted effort.

The Binary Search Debugging Strategy

One of the most powerful debugging strategies is binary search through your pipeline, dividing it into halves and determining which half contains the bug, then recursively subdividing the problematic half until you isolate the issue. This strategy works because machine learning pipelines are sequences of operations where data flows from one step to the next, and bugs in early steps often create symptoms in later steps that mislead you about the bug’s location.

To apply binary search debugging, you identify the midpoint of your pipeline and verify that everything works correctly up to that point. For a pipeline that loads data, preprocesses it, trains a model, and evaluates results, the midpoint might be after preprocessing. You verify that data loaded correctly by examining a few examples in detail. You verify that preprocessing produced sensible output by inspecting transformed features. If everything up to preprocessing works correctly, you know the bug must be in training or evaluation. You have eliminated half the pipeline from consideration. You then subdivide the remaining half, checking if training produced sensible model parameters. If training worked, the bug is in evaluation. If training failed, the bug is in training configuration or the training loop.

This binary division continues until you isolate the bug to a specific operation or small code section. The power of binary search is its logarithmic complexity. A pipeline with sixteen steps requires at most four subdivisions to isolate the bug to one step, which is much faster than checking all sixteen steps sequentially. The key is choosing appropriate checkpoints where you can meaningfully verify correctness, which requires understanding your pipeline’s structure and what correct intermediate results look like.

The Minimal Reproducible Example Strategy

When facing complex bugs in large codebases, creating minimal reproducible examples that demonstrate the bug in simplified settings often accelerates debugging. The process of simplification itself frequently reveals the bug because you discover which components are necessary to trigger the failure and which are irrelevant. Moreover, minimal examples run faster and are easier to inspect than full complex pipelines.

To create a minimal example, you start with your full buggy code and progressively remove components while verifying the bug persists. If your bug appears during training a complex neural network on a large dataset, you might first try replacing your neural network with a simple linear model. If the bug disappears, you know something specific to the neural network architecture causes it. If the bug persists, the architecture is not the issue and you can debug the simpler model. You might next try training on a tiny subset of data, perhaps just ten examples. If the bug persists, you have a much faster debugging cycle. You might replace your custom data loading with generating synthetic data that has similar structure. This progressive simplification isolates what triggers the bug.

Sometimes bugs disappear during simplification, which is itself informative. If a bug only appears with large datasets, that suggests a problem triggered by data characteristics like distribution or scale. If a bug only appears with complex architectures, that points to architecture-specific issues. Each piece of information narrows possibilities even when it does not immediately reveal the bug.

The Comparison Strategy

Comparing buggy code to working reference implementations provides powerful debugging leverage. If you have a working implementation from a tutorial or library and your modified version fails, systematically comparing them identifies differences that might cause the failure. This comparison strategy is particularly effective for debugging implementations of algorithms from papers where you are replicating known approaches.

The comparison process involves running both implementations side by side and examining intermediate results at corresponding points. You might run both on the same data with the same random seeds and compare feature matrices after preprocessing, model outputs after forward passes, gradients after backward passes, and parameter updates after optimization steps. Differences reveal where your implementation diverges from the working version.

Starting from identical inputs and finding where outputs first differ identifies exactly which operation contains the bug. If preprocessing produces identical outputs but model forward passes differ, the bug is in how you implemented the model architecture. If forward passes match but gradients differ, the bug is in backward pass implementation. This differential debugging efficiently isolates problems by leveraging working code as ground truth.

The Progressive Complexity Strategy

When developing new machine learning code, building progressively from simple cases to complex ones while verifying correctness at each stage prevents complex bugs from emerging. This strategy is more about bug prevention than debugging existing code, but understanding it helps when you need to refactor buggy code into a working state.

You start by implementing the simplest possible version of your system and verifying it works perfectly on trivial cases. For a classification problem, you might start with a dataset of ten examples from two classes with one feature, where the classes are perfectly separated. You train a simple model and verify it achieves perfect accuracy. This trivial case has obvious correct behavior that you can verify visually and numerically. Once this works, you add complexity incrementally. You might increase to one hundred examples, then add more features, then add more classes, then introduce class overlap that prevents perfect separation, then scale to full dataset size. At each step, you verify behavior is sensible before adding more complexity.

This progressive approach means bugs are introduced in small, controlled increments. When something breaks, you know it relates to the complexity you just added. Debugging is much easier than if you had built the full complex system at once and found nothing worked. Moreover, having working simple versions gives you reference points for comparison and sanity checks when debugging the complex version.

Common Machine Learning Bugs and How to Find Them

Understanding common bug patterns helps you recognize them quickly when they appear and know what evidence to look for when debugging. These patterns appear so frequently across machine learning projects that experienced practitioners immediately suspect them when observing certain symptoms.

Data Loading and Preprocessing Bugs

Data problems are among the most common sources of machine learning bugs because data handling involves many opportunities for errors. One frequent bug is feature-target misalignment where features and targets do not correspond properly because of shuffling one but not the other, or merging data from different sources that have different ordering. This bug manifests as models that train but learn nothing useful because they are trying to predict targets that are essentially random relative to the features they receive.

To detect feature-target misalignment, you should manually inspect a few examples and verify that the target makes sense given the features. For a sentiment classification task, check that negative sentiment examples actually have negative text and positive examples have positive text. For regression, check that high target values correspond to feature patterns you would expect to predict high values. This manual inspection catches misalignment that would otherwise be invisible.

Another common data bug is incorrect feature scaling where features are scaled in training but not in testing, or scaled using test data statistics rather than training data statistics, or not scaled at all when the model expects scaled features. This creates train-test distribution mismatch where the model trained on one data distribution but tested on a different one. Symptoms include good training performance but poor test performance, or test predictions that seem to ignore input features and just predict some constant value.

To detect scaling bugs, you should verify that both training and test feature matrices have similar statistical properties after preprocessing. Computing and comparing means and standard deviations across features for training and test sets reveals distribution mismatches. Training features should have standardized statistics if you applied standardization. Test features should have similar but not identical statistics because they are transformed using training statistics rather than being standardized independently.

Missing value bugs occur when missing values are not handled consistently or are handled incorrectly. Forgetting to impute missing values means you pass NaN values to models that cannot handle them, typically causing errors. Imputing using test data statistics creates leakage. Imputing before splitting data also creates leakage. Using inappropriate imputation strategies such as mean imputation for categorical variables or mode imputation for continuous variables creates nonsensical values that corrupt training.

To catch missing value bugs, you should add explicit checks after loading data that verify no missing values remain unless your model can handle them. Computing data.isnull parenthesis parenthesis.sum parenthesis parenthesis for pandas DataFrames shows missing value counts per column. Non-zero counts for columns you believed had no missing values indicate either that your imputation did not run or that it failed to handle all missing values.

Model Architecture Bugs

Model architecture bugs are particularly common when implementing neural networks from scratch or customizing architectures. Dimension mismatches where layer output dimensions do not match subsequent layer input dimensions cause errors during forward passes. These are relatively easy to debug because they produce clear error messages indicating which dimensions do not align. However, you must understand how different layers transform dimensions to fix the errors properly.

To debug dimension errors, you should trace dimension transformations through your network manually and verify they match what your code implements. If you intend to transform a batch of thirty-two images of size three by two hundred twenty-four by two hundred twenty-four through a convolutional layer, you need to verify the layer configuration produces the expected output size. Adding print statements that show tensor shapes at each layer helps you verify dimensions match expectations throughout the network.

Activation function bugs involve using inappropriate activation functions or applying them incorrectly. Using ReLU on the final layer of a regression network that should output negative values prevents the network from learning to make negative predictions. Forgetting to apply activation functions means layers are all linear, reducing multi-layer networks to equivalent single-layer networks that cannot learn complex patterns. Applying activation functions to loss values or gradients where they should not appear corrupts training.

Symptoms of activation bugs include inability to learn despite otherwise correct configuration, or learning that produces predictions in wrong ranges such as a classifier that only predicts probabilities near zero or near one but never intermediate values. To debug activation bugs, you should verify that each layer has appropriate activation and that activations are applied to layer outputs but not to other quantities. Checking the mathematical definitions of your operations confirms that non-linearities appear where they should and are absent where they should not.

Training Loop Bugs

Training loop bugs affect the optimization process that adjusts model parameters. A common bug is forgetting to zero gradients between batches, causing gradients to accumulate across batches rather than being computed fresh for each batch. This accumulation makes gradients grow increasingly large and unstable, eventually causing numerical overflow or divergence.

Symptoms of gradient accumulation bugs include training that starts normally but gradually becomes unstable, with losses oscillating or diverging after many iterations. To debug this, you should verify that your training loop explicitly zeros gradients before computing them for each new batch. In PyTorch, this means calling optimizer.zero_grad parenthesis parenthesis before computing loss and calling loss.backward parenthesis parenthesis. Forgetting this call is a classic bug that every deep learning practitioner encounters eventually.

Another training bug is applying gradients to wrong parameters or with wrong signs. If you accidentally add gradients instead of subtracting them, you move parameters in the direction of increasing loss rather than decreasing loss, causing loss to grow during training. If you update only a subset of parameters due to incorrect optimizer configuration, the model cannot fully optimize because some parameters never change.

To catch gradient update bugs, you should verify that training loss decreases on first several batches. If loss increases or stays constant, something is fundamentally wrong with gradient updates. Checking parameter values before and after updates confirms that parameters actually change and that the changes align with gradient directions. Computing the dot product between gradient vectors and parameter update vectors should be negative because updates oppose gradient directions for gradient descent.

Learning rate bugs involve using learning rates that are too large, causing training to diverge, or too small, causing training to make negligible progress. Symptoms of learning rate issues include loss oscillating wildly for too-large rates or loss decreasing imperceptibly slowly for too-small rates. The solution involves trying learning rates spanning several orders of magnitude to find a range that enables stable, reasonably fast convergence.

To debug learning rate issues systematically, you should run training with learning rates differing by factors of ten, such as zero point zero zero one, zero point zero one, zero point one, and one point zero, and observe which produces best loss curves. Plotting loss curves for different learning rates on the same axes makes relative behavior obvious. The optimal learning rate typically lies between the rate that causes divergence and the rate that makes progress too slowly.

Evaluation and Metric Bugs

Evaluation bugs corrupt your assessment of model performance, leading to incorrect conclusions about which models work well. A common evaluation bug is computing metrics on training data instead of test data, or on only a subset of test data, making performance estimates unrepresentative. Another bug is comparing predictions to wrong targets, such as comparing to original targets instead of preprocessed targets when preprocessing affected target values.

To catch evaluation bugs, you should verify the sizes of prediction and target arrays match and that both have the expected number of examples. You should manually inspect a few predictions and targets to verify they seem plausibly matched. Computing evaluation metrics should use clearly labeled test data variables rather than ambiguously named variables that might accidentally refer to training data.

Metric implementation bugs occur when you implement metrics from scratch and make mistakes in the formulas. Using sum instead of mean for averaging, dividing by wrong counts, or applying wrong mathematical operations all create incorrect metric values. Symptoms include metrics that produce values outside expected ranges or that do not agree with metric values from standard libraries.

To prevent metric bugs, you should use standard implementations from libraries like scikit-learn rather than implementing metrics yourself when possible. If you must implement custom metrics, you should verify them on simple cases where you can compute expected values manually. Creating a tiny dataset where you know what the metric should be and checking that your implementation produces that value validates your implementation.

Debugging Tools and Techniques

Beyond systematic debugging processes and understanding common bugs, using appropriate tools accelerates debugging by making invisible aspects of code execution visible.

Strategic Use of Print Statements

Print statements are often dismissed as primitive debugging tools, but used strategically they provide powerful insights into code behavior. The key is printing informative values at strategic locations rather than littering code with prints everywhere. You should print shapes of tensors and arrays to verify dimensions match expectations. You should print summary statistics like means, minimums, and maximums of numerical arrays to detect anomalous values. You should print sample elements from data structures to verify contents are as expected.

Effective print-based debugging involves adding prints progressively as you narrow your search. You start by printing at coarse-grained checkpoints to verify which major pipeline sections work. Once you identify a problematic section, you add finer-grained prints within that section to isolate the specific operation causing problems. This progressive refinement focuses prints on relevant areas rather than overwhelming you with prints throughout the entire codebase.

Formatting prints clearly makes them more informative. Prefixing prints with descriptive labels like “After preprocessing, features shape:” helps you understand what each print represents when you have many prints in your output. Using f-strings or format methods to create readable output with alignment and precision control makes numerical values easier to interpret. Printing shapes alongside a few sample values gives you both structural and content information from a single print.

Using Python Debuggers

Python’s built-in debugger pdb and enhanced variants like ipdb provide interactive debugging where you can pause execution, inspect variables, and step through code line by line. Debuggers are particularly useful for understanding execution flow in complex code and for examining state at specific points without adding explicit print statements.

To use a debugger, you import it and set breakpoints in your code by calling pdb.set_trace parenthesis parenthesis or using the breakpoint parenthesis parenthesis built-in function. When execution reaches a breakpoint, the program pauses and gives you an interactive prompt where you can examine variables, evaluate expressions, and control execution. You can print variables by simply typing their names. You can evaluate arbitrary Python expressions to compute derived values. You can step to the next line, continue execution until the next breakpoint, or execute specific statements.

Debuggers excel at understanding why code behaves unexpectedly in specific situations. If you know a bug occurs on a particular data example, you can set a breakpoint before processing that example and step through the processing to see exactly where things go wrong. This detailed step-through would be tedious with print statements but is natural with a debugger.

However, debuggers have limitations for machine learning code. Debugging large tensor operations or loops over huge datasets is impractical because stepping through thousands of iterations takes too long. Debuggers cannot easily show you high-level patterns in numerical data or visualize distributions. For these tasks, logging numerical summaries and creating visualizations works better than interactive debugging.

Logging for Long-Running Training

Machine learning training often runs for hours or days, making it impractical to watch the entire process interactively. Logging enables you to record information about training progress, then examine logs afterward to understand what happened. Python’s logging module provides flexible logging infrastructure for creating log files, controlling log verbosity, and organizing log messages.

Setting up logging involves creating a logger object, configuring handlers that write logs to files or consoles, and setting log levels that control what gets logged. You then emit log messages throughout your code at appropriate levels. Debug level messages capture detailed information useful for debugging. Info level messages record normal execution milestones like epoch completions. Warning level messages highlight concerning situations like unexpectedly high losses. Error level messages record failures.

For training, you should log metrics like training and validation loss and accuracy at regular intervals such as each epoch or every several batches. This creates a record of training progress that you can analyze to understand whether training is converging, diverging, oscillating, or making steady progress. You should log learning rates if they change during training, batch sizes, and any other training hyperparameters that might affect behavior. This documentation helps you understand training runs and compare different experiments.

Logs become particularly valuable when training fails after many hours. Without logs, you must rerun training with additional instrumentation to understand what went wrong. With comprehensive logs, you can examine what happened during the failed run without repeating the expensive computation. This makes logs essential for production machine learning systems where training failures cost significant compute resources.

Assertions and Validation Checks

Rather than waiting for bugs to cause visible failures, adding assertions throughout your code checks assumptions and catches bugs at their source before they corrupt later computations. Assertions verify conditions that should always hold, raising errors immediately when they are violated rather than letting invalid states propagate.

You should assert shape constraints after operations that transform tensor dimensions. If a reshaping operation should produce a two-dimensional array with specific dimensions, assert that the result shape equals the expected shape. If you expect all values in a tensor to be non-negative after applying an activation, assert that the minimum value is non-negative. If you expect probabilities to sum to one for each example, assert that the sum along the appropriate axis equals one.

Assertions serve as executable documentation of your assumptions. When someone reads your code and sees an assertion, they immediately understand that you designed the code expecting that condition to hold. If the condition is violated, the assertion failure points directly to the problematic location rather than letting the bug surface later in confusing ways. This early detection dramatically simplifies debugging.

The cost of assertions is negligible for most machine learning code because assertions check properties of intermediate results rather than running expensive additional computations. The protection they provide far outweighs the minor performance overhead. In production systems where performance is critical, you can disable assertions, but during development and debugging, they should always be enabled.

Testing Machine Learning Code

Beyond debugging existing bugs, writing tests prevents bugs from occurring by verifying code correctness before and after changes. Testing machine learning code requires different approaches than testing traditional software because of machine learning’s stochastic and numerical nature.

Unit Tests for Deterministic Components

Many machine learning code components are deterministic and can be tested using standard unit testing approaches. Data preprocessing functions that normalize features, encoding functions that convert categorical variables to numerical form, and metric computation functions that calculate evaluation metrics all produce deterministic outputs from given inputs and can be tested by comparing computed outputs to expected outputs.

Writing unit tests involves creating small test functions that exercise code with known inputs and verify outputs match expectations. For a function that normalizes features by subtracting mean and dividing by standard deviation, you create a simple test array with known statistics, pass it to the function, and verify the output has mean zero and standard deviation one. For a function that computes classification accuracy, you create example predictions and labels where you know the correct accuracy, compute accuracy with your function, and verify it matches the expected value.

Testing frameworks like pytest make writing and running tests straightforward. You write test functions that exercise code and make assertions about results. Running pytest automatically discovers and runs all test functions, reporting which pass and which fail. This automation means you can quickly verify that changes did not break existing functionality by running the full test suite after each modification.

For machine learning code, you should write unit tests for all data preprocessing functions, metric computations, custom loss functions, and any utility functions that have deterministic behavior. These tests catch bugs early and give you confidence that individual components work correctly, allowing you to focus debugging effort on integration issues and model-specific problems.

Testing with Synthetic Data

Testing on real data is challenging because you rarely know exactly what outputs should be. Synthetic data where you control all characteristics enables targeted testing. You can create datasets with known properties and verify your code handles them correctly. For a classification problem, you might create perfectly separable classes and verify that a sufficiently flexible model trained on this data achieves perfect accuracy. Failing to achieve perfect accuracy on perfectly separable data indicates a bug in model training or evaluation.

Synthetic data tests also help verify that code handles edge cases properly. You can create data with no variance in some features to verify preprocessing handles constant features correctly. You can create data with perfect correlations between features to test multicollinearity handling. You can create data with extreme values to test whether code handles outliers appropriately. Each synthetic dataset targets a specific assumption or property that your code should handle correctly.

Creating synthetic data requires understanding your problem domain well enough to know what data characteristics matter. For image classification, you might create synthetic images with distinctive patterns for each class and verify that a convolutional network learns to classify them. For time series prediction, you might generate series with known patterns like trends or seasonality and verify that models capture these patterns. The more realistic your synthetic data while still having known properties, the more valuable the tests.

Integration Tests for Pipelines

While unit tests verify individual components, integration tests verify that components work together correctly. A machine learning pipeline integration test might load data, preprocess it, train a model, and evaluate results, verifying that the entire pipeline runs without errors and produces sensible outputs.

Integration tests catch bugs that emerge from component interactions even when components individually work correctly. If your data loader produces data in one format but your preprocessing expects a different format, components are individually correct but incompatible. If your model expects a specific feature ordering but preprocessing produces a different ordering, the integration fails despite each piece being internally correct.

For integration testing, you typically use small datasets and simple models that run quickly, enabling fast test execution. You verify that training produces models whose training loss decreases over several epochs, that evaluation produces metric values in plausible ranges, and that predictions have expected properties like correct shapes and value ranges. You do not necessarily verify exact metric values since these depend on random initialization and stochastic training, but you verify they are reasonable.

Running integration tests before committing code changes prevents merging changes that break the pipeline. This continuous verification maintains a working codebase rather than allowing bugs to accumulate until the entire system is broken. Many teams run integration tests automatically on every code commit using continuous integration systems that provide immediate feedback about breakage.

Deterministic Testing with Fixed Random Seeds

The stochastic nature of machine learning makes testing challenging because results vary between runs. Setting fixed random seeds eliminates this variability during testing, enabling you to verify that code produces consistent results for given inputs and seeds. While production code might use different random seeds for different runs to explore various initializations, test code should use fixed seeds to enable reproducible verification.

Setting random seeds involves calling numpy.random.seed parenthesis seed_value parenthesis for NumPy randomness and similar seed-setting functions for other libraries that use randomness. In PyTorch, you set torch.manual_seed parenthesis seed_value parenthesis for CPU randomness and additional seeds for GPU randomness. In TensorFlow, you set tensorflow.random.set_seed parenthesis seed_value parenthesis. Setting all relevant seeds ensures complete reproducibility.

With fixed seeds, you can test that training produces the same final metrics after the same number of epochs, that model predictions are identical on the same inputs, and that data preprocessing produces identical outputs. This deterministic testing catches bugs that affect randomness handling, such as forgetting to set seeds in some operations or inadvertently introducing new sources of randomness that were not properly seeded.

However, you should not rely solely on seeded determinism for testing. Some bugs only manifest with certain random seeds, and testing only one seed might miss them. Good testing combines deterministic tests with fixed seeds and statistical tests that verify properties hold across multiple random seeds. For instance, you might verify that training with different seeds consistently produces losses that decrease and that the variance in final metrics across seeds is reasonable.

Debugging Specific Machine Learning Frameworks

Different machine learning frameworks have specific debugging considerations and tools that leverage framework features. Understanding framework-specific debugging approaches makes debugging more efficient when working with particular frameworks.

Debugging scikit-learn Pipelines

Scikit-learn pipelines encapsulate preprocessing and modeling steps in a single object, which aids reproducibility but can complicate debugging when something goes wrong. To debug pipelines, you need to access intermediate steps and inspect their behavior individually. Pipelines have a named_steps attribute that provides dictionary access to individual steps by name, allowing you to call methods on specific steps or examine their state.

If a pipeline’s predictions seem wrong, you can extract the preprocessing steps and apply them to data separately to verify they work correctly. You can access fitted preprocessing transformers to examine their learned parameters such as the means and standard deviations learned by a StandardScaler. You can manually apply transformations to test data and verify they produce expected results before using them in the full pipeline.

Common scikit-learn bugs include forgetting that pipelines fit on training data should be used to transform both training and test data, not refit on test data. Debugging this requires verifying that you call pipeline.fit parenthesis X_train, y_train parenthesis to fit the pipeline, then use pipeline.predict parenthesis X_test parenthesis without calling fit again. Another common bug is using raw column names from the original DataFrame after preprocessing when the pipeline has transformed or reordered columns. Pipelines typically output NumPy arrays without column names, requiring you to track column transformations manually or use ColumnTransformer with named transformers to maintain mappings.

Debugging PyTorch Models

PyTorch provides several debugging tools specific to its dynamic computational graph framework. The register_hook functionality allows you to attach custom debugging functions to tensors that execute during backward passes, enabling you to inspect gradients and intermediate values during backpropagation without modifying model code. This is particularly useful for diagnosing gradient flow problems in deep networks.

PyTorch’s anomaly detection mode can be enabled with torch.autograd.set_detect_anomaly parenthesis True parenthesis, causing PyTorch to track all operations and provide detailed information when NaN or infinity values appear in gradients. This tracking has performance overhead but provides invaluable debugging information for numerical issues that otherwise manifest as inscrutable failures.

Common PyTorch bugs include tensor device mismatches where some tensors are on CPU and others on GPU, causing errors when operations try to combine them. Debugging involves checking tensor.device for all tensors involved in failing operations and explicitly moving tensors to the correct device. Another bug is gradient accumulation discussed earlier, debugged by verifying optimizer.zero_grad parenthesis parenthesis is called appropriately. Shape mismatches in PyTorch produce relatively clear error messages indicating expected and actual shapes, making them easier to debug by reshaping tensors appropriately.

Debugging TensorFlow and Keras Models

TensorFlow’s eager execution mode, which is default in TensorFlow 2, makes debugging much easier than the earlier graph-based execution because operations execute immediately and you can inspect values interactively. You can add print statements that actually print during model execution, use regular Python debuggers, and examine tensor values at any point in your code.

For debugging Keras models specifically, you can create intermediate models that output activations from internal layers, allowing you to examine what the model is computing at each layer without modifying the original model architecture. This is useful for verifying that activations have expected properties and for diagnosing where in a deep network problems first appear.

Common TensorFlow bugs include shape errors that occur during model building or training due to incorrect layer configurations. TensorFlow’s error messages for shape mismatches have improved substantially in TensorFlow 2 and typically indicate which layers have incompatible shapes. Another common bug is mixing NumPy arrays and TensorFlow tensors inappropriately, which can cause type errors or unexpected behavior. Converting explicitly with tf.convert_to_tensor or using .numpy parenthesis parenthesis to convert tensors to arrays makes data type handling explicit and prevents confusion.

Conclusion: Building Debugging Proficiency

You now have comprehensive understanding of debugging and testing machine learning code, from recognizing how machine learning bugs differ from traditional software bugs through systematic debugging processes to testing practices that prevent bugs. You understand common bug categories and how to diagnose them. You know how to use debugging tools including print statements, debuggers, logging, and assertions effectively. You can write tests that verify machine learning code correctness. You understand framework-specific debugging considerations for popular machine learning libraries.

The investment in debugging skills transforms your machine learning development experience. Rather than feeling helpless when code does not work, you have systematic approaches to isolate and fix problems. Rather than making random changes hoping something works, you form testable hypotheses and gather evidence. Rather than debugging the same issues repeatedly, you write tests that prevent recurrence. This proficiency in debugging and testing makes you a more capable and more productive machine learning engineer.

As you continue developing machine learning applications, you will encounter new bugs and debugging challenges. Each debugging experience builds your intuition about where to look for different problems and what evidence indicates different bug categories. You will develop personal debugging workflows that combine the techniques from this article in ways that match your thinking style. You will learn to recognize code smells that suggest potential bugs before they manifest as actual failures. This accumulating expertise makes debugging progressively easier and faster.

Welcome to systematic debugging and testing of machine learning code. Continue practicing these techniques on your projects, build your debugging intuition through experience, write tests that catch problems early, and develop the disciplined habits that prevent bugs from occurring in the first place. The combination of systematic debugging processes and comprehensive testing makes your machine learning development robust, maintainable, and reliable.