Introduction: The Invisible Force Shaping Your Prints

When you watch a 3D printer at work, the drama unfolds in the visible dance of the print head moving across the build plate, depositing layer after layer of plastic. What you might not immediately notice are the small fans running continuously throughout the print, directing streams of air at precisely the right locations and intensities. These cooling fans seem like simple accessories, perhaps even optional extras, yet they play absolutely critical roles in determining whether your prints succeed or fail, whether surfaces are smooth or messy, and whether complex features print accurately or collapse into molten blobs.

The challenge that cooling fans address is fundamental to the physics of FDM printing. The printer deposits molten plastic that’s heated to temperatures between one hundred eighty and two hundred sixty degrees Celsius or even higher, depending on the material. This plastic is liquid or semi-liquid when it emerges from the nozzle, and it needs to solidify quickly enough to support the next layer that will be deposited on top of it. If the plastic remains too hot for too long, several problems emerge. The layers don’t hold their shape, causing features to droop or sag. Overhangs that should cantilever out from lower layers instead collapse. Bridges that should span gaps fall and create stringy messes. Small details merge together as heat from successive layers keeps previous layers soft enough to deform.

Cooling fans solve these problems by accelerating the solidification process. By blowing air across freshly deposited plastic, fans remove heat much faster than passive cooling through radiation and natural convection could accomplish. This forced convection rapidly drops the plastic’s temperature below its glass transition point where it becomes rigid enough to support subsequent layers. The difference between adequate cooling and inadequate cooling can be dramatic, with identical models printing perfectly with proper cooling but failing completely without it.

However, cooling in 3D printing is not as simple as pointing a fan at the print and running it at maximum speed all the time. Different materials have different cooling requirements, with some plastics benefiting from aggressive cooling while others actually print better with minimal or no cooling at all. The timing of when cooling starts during a print affects first layer adhesion and part strength. The direction and distribution of airflow can create uneven cooling that causes warping or introduces mechanical stress into parts. Managing cooling effectively requires understanding not just that cooling matters, but when to cool, how much to cool, where to direct the cooling air, and what trade-offs you’re making with different cooling strategies.

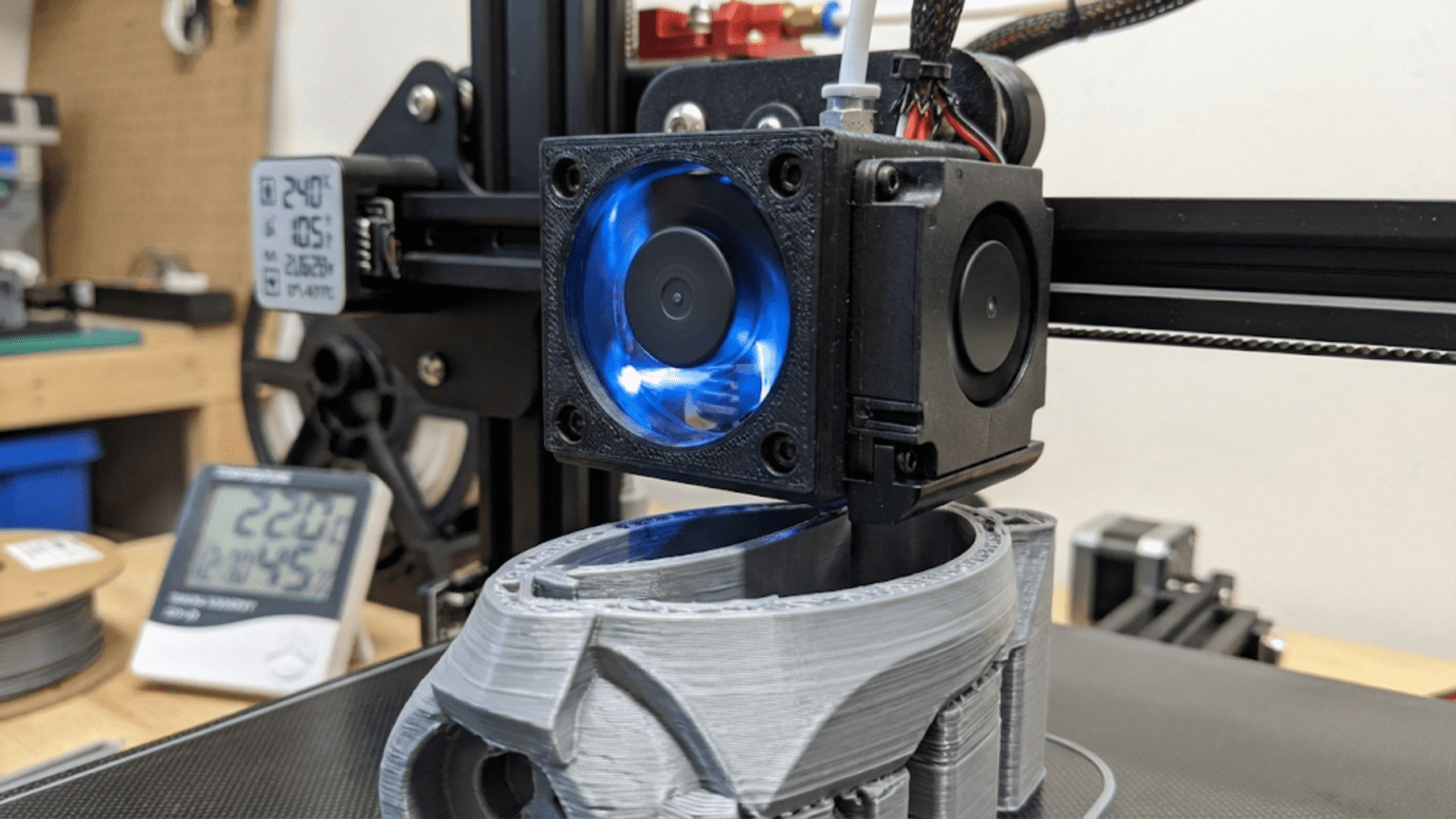

Modern 3D printers typically include at least two distinct fan systems serving different purposes. The part cooling fan, sometimes called the layer cooling fan or print cooling fan, specifically targets the freshly printed material just after it exits the nozzle. This fan is the one that varies during printing, sometimes running at full speed and sometimes at reduced speeds or even turning off entirely depending on what’s being printed. The hotend cooling fan, also called the heat sink fan, serves a completely different purpose by keeping the cold end of the hotend cool to prevent heat creep and maintain proper filament feeding. This fan typically runs continuously at full speed whenever the hotend is hot and is not adjustable during printing.

Understanding the distinct roles of these fan systems, how to optimize cooling for different materials and geometries, and how to troubleshoot cooling-related problems represents essential knowledge for achieving consistently successful prints. Poor cooling is behind many common print quality issues including poor overhangs, failed bridges, messy small details, and layer adhesion problems, yet beginners often don’t recognize these symptoms as cooling-related and waste time pursuing other solutions. This article explores cooling comprehensively, providing the knowledge you need to use cooling effectively as a tool for improving print quality and success rates.

Part Cooling vs Hotend Cooling: Two Systems, Two Purposes

The first critical distinction to understand is that your 3D printer has two completely separate cooling systems that serve fundamentally different purposes. Confusing these systems or misunderstanding their roles leads to incorrect troubleshooting and missed opportunities for optimization. Let’s examine each system in detail to understand what it does, why it’s necessary, and how it should be managed.

The part cooling fan exists to cool the plastic after it’s been deposited on the print. This fan is typically mounted on the print head assembly, positioned to blow air directly at the spot where plastic exits the nozzle and lands on the print. The goal is to rapidly solidify freshly extruded plastic so it can support additional layers without deforming. Think of the part cooling fan as a hair dryer in reverse, instead of adding heat to change material state, it removes heat to achieve a state change from molten to solid.

Part cooling fans are highly variable in their operation. The slicer software generates commands that turn the fan on or off and adjust its speed throughout the print based on the geometry being printed and the material being used. During the first layer, part cooling is typically disabled or set to very low speeds because you want the first layer to remain slightly soft and maximize adhesion to the build plate. After the first few layers, cooling ramps up to whatever speed is optimal for the material and features being printed. On small layers that complete quickly and don’t have much time to cool naturally, the fan might run at maximum speed to prevent heat buildup. On large layers that take longer to print, the fan might run slower because there’s adequate time for natural cooling.

The physical design of part cooling systems varies significantly between printers. Some use a single radial blower fan that directs air through a duct toward the nozzle from one side. More sophisticated designs use dual fans or a single fan with ducting that splits the airflow to come from multiple directions, providing more uniform cooling around the nozzle. The most advanced systems use ring or toroidal ducts that surround the nozzle completely, directing air evenly from all directions. This omni-directional cooling reduces the chance of uneven cooling that can cause warping or introduce asymmetric mechanical properties into printed parts.

The effectiveness of part cooling depends not just on the fan itself but on the ducting and airflow design. A powerful fan with poor ducting that doesn’t actually direct air at the right location provides less cooling than a modest fan with well-designed ducts that focus airflow precisely where needed. The distance between the fan output and the print surface matters, as does the angle of the airflow. Many users upgrade their stock part cooling systems with improved ducts that can be printed as 3D printed parts themselves, using designs shared by the community that optimize airflow for specific printer models.

The hotend cooling fan serves a completely different purpose, maintaining the thermal barrier between the hot melt zone and the cold feed zone in the hotend. This fan cools the heat sink or heat break, preventing heat from migrating upward into areas where filament should remain solid. Without adequate hotend cooling, heat creep occurs where heat softens filament before it enters the melt zone, causing jams and extrusion failures. We covered this in detail in the hotend article, but it’s worth emphasizing here that hotend cooling is about cooling the hotend assembly itself, not the printed plastic.

Hotend cooling fans run continuously at a fixed speed whenever the hotend is at or above printing temperature. This constant operation is necessary because heat creep can develop quickly if cooling stops even briefly. Most printer firmware monitors the hotend cooling fan and will pause or stop printing if this fan fails, recognizing that continued printing without it will inevitably lead to a jam. Unlike part cooling fans which the slicer controls dynamically, hotend cooling is managed by firmware at a lower level and typically isn’t something you adjust during normal printing.

The distinction between these two fan systems is so important that getting them confused leads to serious problems. If you accidentally connect your hotend cooling fan to the part cooling fan port, the hotend fan will turn on and off during printing, likely causing heat creep and clogs. If you connect the part cooling fan to the hotend cooling port, it will run continuously at full speed, probably over-cooling materials that print better with less cooling and potentially causing warping and poor layer adhesion. Always verify that each fan is connected to its correct port when setting up or troubleshooting a printer.

Some printers include additional fans beyond these two primary systems. Power supply fans cool the printer’s power supply, particularly important for high-power supplies that run heated beds. Controller board fans cool the mainboard and stepper motor drivers, preventing thermal throttling or component failure. Enclosure fans can help manage chamber temperature in enclosed printers. These auxiliary fans serve specialized purposes but aren’t directly involved in the printing process like part cooling and hotend cooling are.

Understanding this two-system framework helps you diagnose problems correctly. If you’re experiencing poor overhangs or bridges, that’s a part cooling issue requiring adjustment of part cooling fan speeds or improving part cooling airflow. If you’re getting clogs that develop during printing or inconsistent extrusion, that might be a hotend cooling issue indicating the hotend fan isn’t working properly or the heat sink needs better cooling. Correctly attributing symptoms to the right cooling system points you toward effective solutions.

How Part Cooling Affects Print Quality and Success

The impact of part cooling on print quality manifests in multiple ways across different aspects of printing. Understanding these specific effects helps you recognize cooling-related problems when they occur and appreciate why cooling adjustments can dramatically improve results in particular situations. Let’s examine each major way that part cooling influences what comes off your printer.

Overhangs represent one of the most cooling-sensitive features in 3D printing. An overhang is any surface that extends outward beyond the layer below it at an angle from vertical. Shallow overhangs, close to vertical, present minimal challenge because each layer sits almost entirely on the previous layer. Steep overhangs, approaching horizontal, present maximum challenge because each layer extends far beyond the previous layer with only a small contact area for support. The plastic being deposited for steep overhangs is essentially being placed in midair, and it needs to cool and solidify almost instantly or it will droop under its own weight.

Proper part cooling makes the difference between successful overhangs and sagging, droopy messes. When cooling is adequate, freshly deposited plastic cools rapidly enough that it becomes rigid before gravity can pull it downward. The layer freezes in place, creating a solid surface that the next layer can build upon. Without sufficient cooling, the plastic remains soft for longer, allowing gravity to deform it before it solidifies. This creates the characteristic sagging appearance of under-cooled overhangs where surfaces that should be smooth and angular instead look wavy and droopy.

The maximum overhang angle your printer can successfully print depends significantly on cooling effectiveness. With excellent cooling, you might achieve clean overhangs up to sixty or even seventy degrees from vertical. With poor cooling, you might struggle with anything beyond forty-five degrees. This is why upgrading to better part cooling, whether through improved ducting or more powerful fans, often enables printing more challenging geometries without support structures.

Bridging, the ability to span gaps by printing material between two supported points with nothing underneath, is perhaps even more dependent on cooling than overhangs. When bridging, the printer extrudes a line of plastic from one support point to another across open air. For short bridges, maybe five to ten millimeters, the plastic’s own stiffness and the tension created by stretching between the two points might be sufficient to prevent sagging. For longer bridges, this becomes inadequate and the plastic will sag in the middle, creating a droopy arch rather than a straight span.

Aggressive part cooling enables successful bridging by rapidly solidifying the extruded plastic before it has time to sag significantly. The plastic essentially freezes into a rigid strand quickly enough that it maintains its shape across the gap. With inadequate cooling, even short bridges may fail as the plastic remains soft long enough to droop under its own weight. The visual difference is stark, with good cooling producing straight, clean bridges and poor cooling producing sagging, stringy messes that may even fail to reach the far support point at all.

Small features and fine details benefit tremendously from good cooling. When printing tiny features like small text, thin walls, or intricate surface details, the printer deposits very small amounts of plastic in close proximity. If this plastic doesn’t cool quickly, heat from each successive layer keeps previous layers soft, causing features to blur together or deform. The layers might merge into an indistinct blob rather than maintaining crisp, separate details. Strong cooling ensures each tiny bit of plastic solidifies before the next bit is deposited, preserving sharp, clear details.

This effect is particularly noticeable on small cylindrical features like pins or towers. With good cooling, each circular layer maintains its shape and stacks cleanly on the previous layer. With poor cooling, the tower might develop a bulging or misshapen appearance as layers deform before solidifying. The same print with and without adequate cooling can look remarkably different, with the cooled version showing clean, crisp details and the uncooled version looking blobby and indistinct.

Layer bonding strength, interestingly, has an inverse relationship with cooling. While cooling improves geometric accuracy and enables printing challenging features, it can reduce the strength of bonds between layers. When layers cool very rapidly, they have less time to fuse together while both layers are still hot. The result can be parts that are more brittle and prone to delamination along layer lines. This creates a fundamental trade-off where you must balance the geometric benefits of cooling against the strength benefits of allowing layers to remain hot long enough for good bonding.

This trade-off is why cooling strategies often differ between aesthetic prints where appearance matters most and functional prints where mechanical strength is paramount. Display models might use aggressive cooling to achieve the cleanest possible surface finish and sharpest details, accepting some reduction in strength as the cost. Functional mechanical parts might use more moderate cooling, accepting slightly less perfect overhangs in exchange for better layer adhesion and overall part strength.

Surface finish on vertical walls is also influenced by cooling, though less dramatically than overhangs or bridges. Uniform, consistent cooling helps vertical surfaces print cleanly with smooth layer lines. Uneven cooling or turbulent airflow can create visible artifacts on vertical surfaces where different areas cool at different rates. This is one reason why well-designed cooling ducts that provide uniform airflow are valuable, they produce more consistent results across all surfaces of the print.

Understanding these various effects helps you diagnose problems correctly. If you see drooping overhangs, poor bridges, or mushy small details, the solution is almost certainly increasing part cooling. If you see good geometric accuracy but parts that are brittle and break easily along layer lines, the solution might be reducing cooling slightly to allow better bonding. Recognizing the specific signature of cooling-related issues helps you make appropriate adjustments rather than changing random settings in hope of improvement.

Material-Specific Cooling Requirements

Different materials have dramatically different optimal cooling strategies, with some plastics demanding maximum cooling while others print best with minimal or no cooling at all. Understanding these material-specific requirements is essential for achieving good results and explains why you should adjust cooling settings when switching between materials rather than using one universal cooling strategy for everything. Let’s examine the cooling characteristics and requirements of common 3D printing materials.

PLA stands out as the material most benefiting from aggressive cooling. PLA has a relatively low glass transition temperature around sixty degrees Celsius, meaning it transitions from rigid to soft at relatively low temperatures. This low transition point means PLA cools rapidly and solidifies quickly when cooling air is applied. PLA also has minimal tendency to warp or crack from thermal stress, so the rapid cooling doesn’t cause the mechanical problems it might in other materials. For PLA, running part cooling at or near maximum speed produces the best results in most cases. The aggressive cooling enables crisp overhangs, excellent bridges, and sharp fine details. The main exception is the first few layers where reduced cooling helps with bed adhesion.

Many PLA users simply set their part cooling to one hundred percent for the entire print except the first layer or two where it ramps up from zero. This straightforward cooling strategy works well for PLA’s characteristics. If you’re getting good results with PLA and decide to try other materials, don’t assume the same cooling settings will work, PLA’s friendliness with high cooling is somewhat unique and doesn’t generalize to all materials.

PETG requires more nuanced cooling than PLA. PETG benefits from some cooling to help with overhangs and bridging, but too much cooling can cause layer adhesion problems. PETG has better layer bonding when layers remain warm, and excessive cooling can make parts brittle and prone to delamination. A common strategy for PETG is to use moderate cooling, perhaps thirty to fifty percent fan speed, rather than the maximum cooling used for PLA. This provides enough cooling to handle most geometric challenges while preserving good layer bonding.

Some PETG users vary cooling based on the features being printed, using higher cooling for overhangs and bridges but lower cooling for vertical walls and infill where bonding strength matters more. This adaptive approach requires more sophisticated slicer settings but can produce superior results compared to fixed cooling throughout the print. PETG also tends to be more sensitive to uneven cooling than PLA, making uniform airflow from well-designed ducts more important for avoiding warping.

ABS and similar styrene-based materials present the opposite extreme from PLA when it comes to cooling requirements. ABS prints best with minimal or no part cooling because of its high tendency to warp from thermal stress. When ABS cools rapidly, particularly if different parts of a print cool at different rates, internal stresses develop that cause warping, cracking, or layer delamination. For this reason, ABS prints are often done with part cooling completely disabled or set to very low speeds.

The challenge with minimal cooling on ABS is that overhangs and bridges become more difficult. Without cooling to solidify plastic quickly, overhangs may droop and bridges may sag. This is one reason why ABS prints often benefit from being done in an enclosed printer with elevated chamber temperature, the warm chamber reduces thermal gradients while still allowing enough cooling for geometric features to form. When printing ABS in an open environment, you might need to use support structures for overhangs that would print fine with PLA’s aggressive cooling, accepting the extra support material as the cost of avoiding warping.

Some users printing ABS do enable minimal part cooling, perhaps ten to thirty percent fan speed, specifically for overhangs and bridges while keeping it off for everything else. This targeted cooling approach helps challenging features while minimizing warping risk. However, it requires the slicer to correctly identify which areas need cooling support, and not all slicers handle this well. The safer approach for beginners with ABS is simply keeping part cooling off entirely.

TPU and other flexible filaments have mixed cooling requirements depending on the specific formulation and the hardness of the material. Softer, more flexible TPU often prints better with reduced cooling because the material needs to bond well between layers to avoid separation, and cooling can interfere with this bonding. However, moderate cooling can help with overhangs and dimensional accuracy by solidifying features before they deform. A common approach is using moderate cooling, around thirty to fifty percent, striking a balance between these competing concerns.

Nylon typically prints best with minimal cooling, similar to ABS. Nylon is hygroscopic and prone to warping, and rapid cooling exacerbates these issues. Many nylon prints are done with part cooling entirely disabled or only enabled at very low speeds for extreme overhangs. The trade-off is that nylon without cooling may show softer details and less successful overhangs compared to cooled materials. However, the alternative of warped, cracked, or delaminated prints is worse, so minimal cooling remains the standard recommendation.

Specialty materials like wood-filled, metal-filled, or glow-in-the-dark filaments typically follow the cooling requirements of their base plastic. Wood-filled PLA benefits from cooling similar to pure PLA, though perhaps slightly less aggressive. Metal-filled filaments might need moderate cooling to balance detail against layer adhesion. The particles in composite filaments can affect thermal properties, so some experimentation is often needed to find optimal cooling.

High-temperature engineering materials like polycarbonate, PEEK, or other exotic plastics almost universally require minimal or no cooling and are printed in heated enclosures to maintain high chamber temperatures. The extreme temperatures and thermal sensitivities of these materials make cooling management critical, and getting it wrong causes immediate failures. These materials are beyond beginner scope but it’s worth knowing they exist and have even more demanding cooling requirements than common materials.

The practical implication of these material differences is that your slicer should include material-specific cooling settings in each material profile. When you select PLA, cooling should automatically configure for high speeds. When you select ABS, cooling should be minimal or disabled. This material-aware cooling management prevents the common mistake of switching materials but forgetting to adjust cooling, then wondering why prints are failing in new and interesting ways.

Cooling Strategies for Different Print Scenarios

Beyond material-specific cooling settings, different types of prints and different geometric features benefit from strategic cooling adjustments. Understanding these scenario-based strategies helps you optimize cooling for specific goals whether that’s maximizing quality, ensuring success with difficult geometries, or improving mechanical properties. Let’s explore several common scenarios and their optimal cooling approaches.

First layer cooling requires special attention because the first layer’s primary job is adhering to the build plate, and excessive cooling works against this goal. When plastic cools rapidly, it contracts and tends to pull away from the build surface. The first layer needs to remain slightly warm to maintain maximum adhesion while it’s being deposited. For this reason, most cooling strategies involve disabling part cooling entirely for the first layer or two, only enabling cooling once the foundation is well-established.

Some materials and printers benefit from an even more gradual cooling ramp where cooling increases progressively over the first several layers rather than jumping from off to full speed. This gentler transition reduces thermal shock and warping risk while still bringing cooling online in time to help with features appearing in later layers. Many slicers support setting a layer number at which cooling reaches full speed with automatic ramping from the first layer.

The exception to minimal first layer cooling is when printing very small objects where even the first layer is tiny and completes quickly. In these cases, some cooling might be necessary from the start to prevent heat buildup that would deform even the first layer. However, this is uncommon and most prints benefit from the standard approach of low or no first layer cooling.

Tall thin features like towers, pillars, or spires benefit from maximum cooling because each layer is small and completes quickly, giving little time for natural cooling before the next layer arrives. Without aggressive cooling, heat accumulates in these features and they can become soft enough to deform or even topple. Many slicers include minimum layer time settings that automatically slow down printing and increase cooling when layers complete too quickly, ensuring adequate cooling time even on very small layers.

When you see tall thin features becoming increasingly deformed or leaning as they get taller, the problem is almost always insufficient cooling for those small layers. The solution is either increasing cooling fan speed, enabling and properly configuring minimum layer time settings, or printing multiple objects simultaneously so each layer has more time to cool while the printer works on the other objects. This last approach, called parallel printing, provides cooling time without needing to slow down the printing process itself.

Bridging presents one of the most extreme cooling demands. Successfully bridging gaps requires cooling at maximum speed to solidify the plastic strand as quickly as possible before it can sag. Some slicers allow setting bridge-specific fan speeds that are higher than the general part cooling speed, enabling ultra-aggressive cooling specifically for bridging moves. If your slicer supports this feature, configuring it with maximum or near-maximum bridge cooling can dramatically improve bridge quality even on materials that normally use moderate cooling.

The direction and technique of bridging also matter for cooling effectiveness. Bridges aligned with the airflow direction from your part cooling fan cool more effectively than bridges perpendicular to the airflow. When possible, orienting your model so critical bridges align with fan airflow can improve results. This is a subtle optimization that matters most for marginal situations where bridges are just barely succeeding or failing.

Overhangs benefit from high cooling, but not necessarily maximum cooling in all cases. Moderate overhangs, perhaps up to fifty degrees from vertical, might print fine with normal cooling settings. Extreme overhangs approaching horizontal might need maximum cooling to succeed without supports. Some slicers allow setting overhang-specific fan speeds that kick in only for surfaces exceeding a certain angle threshold. This targeted cooling provides extra help for challenging geometry without over-cooling the entire print.

Infill typically doesn’t need the same cooling as perimeters or external surfaces because infill is internal and doesn’t show. Some slicers allow separate infill cooling settings, and reducing cooling during infill while maintaining higher cooling for perimeters can improve layer bonding and part strength without sacrificing surface quality. This optimization is particularly relevant for functional parts where internal strength matters more than perfect infill appearance.

Large flat surfaces present their own cooling challenges. Uniform cooling across large surfaces prevents warping and curling at corners or edges. However, if your part cooling system blows air primarily from one direction, large flat surfaces might cool unevenly with the side nearest the fan cooling faster than the far side. This uneven cooling can induce warping or introduce mechanical stress that weakens the part. For large flat prints, improving cooling uniformity through better ducting or print orientation can be more important than simply increasing fan speed.

Print orientation interacts with cooling effectiveness because the orientation determines which surfaces face which directions relative to your cooling fan. If you know your fan blows primarily from one side, orienting critical surfaces toward that fan improves cooling on those surfaces. This is yet another factor to consider when choosing optimal print orientation, adding to the considerations of strength, surface quality, and support requirements we discussed in the orientation article.

Multi-material or multi-color prints where different areas use different materials present cooling configuration challenges. You need cooling appropriate for each material, but the slicer might struggle to apply different cooling to different regions within the same layer. The practical solution often involves choosing cooling settings that represent a compromise suitable for all materials being used, even if that compromise isn’t optimal for any single material. Alternatively, splitting the model into separate prints for each material allows optimizing cooling for each part independently.

Diagnosing and Fixing Cooling Problems

Recognizing the symptoms of cooling problems and understanding how to address them helps you quickly resolve issues rather than spending hours troubleshooting in the wrong direction. Let’s examine common cooling-related problems, their characteristic symptoms, and effective solutions for each.

Drooping overhangs appearing as wavy, saggy surfaces on overhanging features almost always indicate insufficient cooling. The freshly deposited plastic isn’t solidifying quickly enough and gravity deforms it before it becomes rigid. The first solution to try is increasing part cooling fan speed. If you’re running at fifty percent, try eighty or one hundred percent. If you’re already at maximum speed, the cooling system itself might be inadequate, either due to poor ducting design, a weak fan, or incorrect fan placement that doesn’t actually direct air at the print effectively.

Before concluding your cooling hardware is inadequate, verify the fan is actually running. It sounds obvious, but cooling problems sometimes result from disconnected fan wires, failed fans, or incorrect slicer settings that disable cooling when it should be enabled. Watch the fan during printing and confirm it spins at the expected speed. Use your hand to feel the airflow and verify air is actually reaching the area where plastic is being deposited. You’d be surprised how often cooling problems turn out to be simple mechanical issues rather than optimization challenges.

If your fan runs properly but overhangs still droop, improving cooling through upgraded ducts or a more powerful fan can help. Many 3D printer communities share improved cooling duct designs that can be printed as upgraded parts for specific printer models. These upgraded ducts often direct airflow more effectively than stock designs, providing better cooling without requiring fan replacement. Installing an upgraded duct is typically a simple modification that can dramatically improve overhang performance.

Failed bridges that sag in the middle or don’t reach the far support point indicate cooling is insufficient for the bridging distance. Again, increasing fan speed is the first solution. Reducing bridging speed can also help by giving more time for cooling to take effect before the next line of plastic is deposited. Some materials simply can’t bridge certain distances reliably even with maximum cooling, and in those cases the solution is redesigning the model to include supports or reduce the required bridge length.

If bridges succeed on one side of the print but fail on the other side, your cooling is probably directional rather than uniform. The successful side receives more airflow while the failed side receives less. Solutions include improving cooling duct design to provide more uniform airflow, rotating the print on the build plate so all critical bridges face the good cooling direction, or accepting the limitation and using supports for bridges in poorly cooled areas.

Warping, particularly on ABS or similar materials, often results from excessive cooling or uneven cooling rather than insufficient cooling. Warping appears as corners or edges lifting from the build plate or upper layers pulling and distorting the print. If you’re experiencing warping while using high part cooling speeds, try reducing cooling or disabling it entirely. For ABS in particular, you want minimal or no part cooling as standard practice. If warping persists with cooling disabled, the problem lies elsewhere, perhaps bed adhesion, ambient temperature, or material properties rather than cooling settings.

Asymmetric warping where one side of the print warps but the other doesn’t often indicates uneven cooling. One side receives more airflow and cools faster, creating thermal stress that causes warping toward the cooler side. Solutions include improving cooling uniformity with better ducts, reducing overall cooling speed to make uneven cooling less impactful, or using an enclosure to reduce thermal gradients by warming the entire chamber.

Rough or blobby small features suggest cooling is inadequate to solidify small amounts of plastic quickly enough. Each layer stays soft long enough to be deformed by the next layer, causing features to blur together. Increasing cooling helps by solidifying each bit of plastic before the next arrives. This is particularly important for small text, fine surface details, or intricate decorative elements where precision matters.

Layer separation or delamination, where layers pull apart either during printing or after the print completes, can result from excessive cooling preventing good layer bonding. This is the classic trade-off where cooling improves geometric accuracy but reduces mechanical strength. If you’re getting good overhangs and bridges but parts are brittle and layers separate easily, try reducing cooling to allow better thermal bonding. This is particularly relevant for functional parts where strength matters more than perfect surface details.

Temperature-related stringing or oozing can sometimes be addressed partly through cooling adjustments. While retraction is the primary tool for controlling stringing, aggressive cooling can help solidify any oozing plastic quickly enough that it doesn’t form visible strings. If you’ve optimized retraction but still see minor stringing, trying slightly higher cooling might help. However, cooling isn’t a substitute for proper retraction tuning and excessive cooling to compensate for poor retraction can cause other problems.

Print surface artifacts like ringing or ghosting are typically mechanical issues related to printer rigidity and motion control, but in rare cases they can be influenced by cooling if the cooling fan creates vibrations or if airflow direction during printing creates slight forces on the print head. If you notice artifacts correlating with fan speed changes, this unusual cause might be relevant. Solutions include ensuring the fan is securely mounted without vibration, verifying ducts aren’t creating aerodynamic forces that affect print head motion, or using slightly different fan speeds to avoid resonant frequencies.

Inconsistent results where identical prints sometimes succeed and sometimes show cooling-related failures suggest environmental factors. Room temperature variations, airflow from HVAC systems, or seasonal changes can affect how much natural cooling occurs and thus how much part cooling fan speed is needed to achieve consistent results. If you notice seasonal patterns to cooling problems, adjusting fan speeds for summer versus winter conditions might help maintain consistency.

Optimizing Your Cooling System

Beyond simply adjusting fan speeds in your slicer, you can make physical improvements to your printer’s cooling system that provide better, more uniform cooling. Understanding these optimization opportunities helps you decide whether upgrades are worth pursuing and guides DIY improvements for users who want to enhance their printer’s cooling capabilities. Let’s explore various ways to optimize cooling hardware.

Fan selection matters significantly for cooling effectiveness. Most printers come with adequate but not exceptional cooling fans, and upgrading to higher-quality or more powerful fans can improve cooling without changing anything else about the system. The main specifications to consider are airflow measured in cubic feet per minute or liters per minute, static pressure which indicates the fan’s ability to push air through restrictive ducting, and noise level if you’re sensitive to printer noise.

For part cooling, radial blower fans are generally more effective than axial fans because blowers generate higher static pressure and can push air more effectively through the narrow ducts and confined spaces typical of printer cooling systems. Most printers use blowers for part cooling, but if yours uses an axial fan, switching to a blower of the same mounting size typically improves performance. Verify voltage compatibility and connector types before purchasing replacement fans.

Higher-performance fans often run at higher voltages than the standard twelve volts common on many printers. Twenty-four volt fans generally move more air than twelve volt fans of the same size, but they require that your printer’s electronics provide twenty-four volt power. Many modern printers do use twenty-four volt systems, but older printers might be twelve volt only. Verify your printer’s specifications before choosing fans, or use voltage converters if you want to use fans at different voltages than your printer natively provides.

Duct design dramatically affects cooling effectiveness even with the same fan. Stock cooling ducts are often compromises balancing ease of manufacturing, cost, and performance. Community-designed upgraded ducts, optimized through testing and iteration, frequently outperform stock ducts significantly. These upgraded ducts are often available as 3D printable models that you can download and print yourself, making the upgrade essentially free beyond a bit of filament and printing time.

When evaluating or designing cooling ducts, several characteristics contribute to effectiveness. The duct should direct airflow directly at the point where plastic exits the nozzle, not above it or below it but right at the deposition point. This ensures maximum cooling of the freshest, hottest plastic. The duct should ideally provide airflow from multiple directions around the nozzle, creating uniform cooling rather than one-sided cooling. This prevents asymmetric cooling that can cause warping or create directional variations in overhang quality.

The duct’s internal geometry should minimize turbulence and flow restrictions. Smooth transitions, gradual curves rather than sharp bends, and avoiding sudden changes in duct cross-section all improve airflow efficiency. A duct with poor internal geometry might restrict airflow so much that even a powerful fan provides inadequate cooling at the print. 3D printing your own ducts allows experimenting with different designs to find what works best for your printer.

Ring ducts or toroidal cooling systems represent the pinnacle of cooling uniformity, surrounding the nozzle completely and directing air from all directions simultaneously. These systems eliminate directionality in cooling and provide the most consistent results across all sides of prints. However, they’re more complex to design and install, sometimes require relocating other components on the print head to make room for the ring duct, and aren’t available for all printer models. For users printing challenging overhangs or seeking maximum quality, the effort of installing a ring duct can be worthwhile.

Fan positioning relative to the nozzle affects cooling effectiveness. The outlet of your cooling duct should be close enough to the nozzle that air reaches the plastic before it disperses and loses velocity. Typically, the duct outlet should be within ten to twenty millimeters of the nozzle tip. However, it also must not interfere with the nozzle’s ability to reach all areas of the build plate or collide with tall prints. This balance sometimes requires careful design or adjustment to optimize.

For hotend cooling, while less variable than part cooling, upgrades can still help. A larger or higher-performance heat sink can improve heat dissipation, making the hotend fan’s job easier. Higher-performance cooling fans for the heat sink provide more reliable cooling margin, reducing heat creep risk. These upgrades are particularly valuable if you print materials that require high temperatures or if you print very quickly with high material flow rates that generate substantial heat.

Maintenance of cooling systems is often overlooked but important for sustained performance. Dust accumulation on fan blades and in ducts reduces airflow over time. Periodically cleaning fans with compressed air or soft brushes maintains their effectiveness. Checking that fans spin freely without bearing noise or wobble prevents failures before they cause print problems. These simple maintenance tasks take just minutes but preserve cooling performance long-term.

Testing cooling improvements objectively requires printing standardized test models before and after modifications. Bridging tests, overhang tests, and detailed small feature prints provide concrete evidence of whether modifications improved performance. Without systematic testing, it’s easy to convince yourself that time-consuming modifications helped when they might have made little practical difference. Objective comparison keeps your optimization efforts focused on changes that actually matter.

Conclusion: Cooling as a Fundamental Tool

Cooling in 3D printing represents far more than just fans blowing air at prints. It’s a sophisticated system of thermal management that enables printing complex geometries, achieving fine details, and producing clean surface finishes that would be impossible without effective cooling. Understanding cooling comprehensively transforms it from a background feature you take for granted into an active tool you wield deliberately to achieve specific outcomes and overcome printing challenges.

The distinction between part cooling and hotend cooling, two completely separate systems serving different purposes, is fundamental to understanding printer operation and troubleshooting effectively. Recognizing which system addresses which problems prevents wasted time trying to fix part quality issues by adjusting hotend cooling or preventing heat creep through part cooling adjustments. This clarity of understanding allows targeted, effective problem-solving.

Material-specific cooling requirements highlight that 3D printing success comes from matching process parameters to material characteristics. PLA’s love of aggressive cooling, ABS’s intolerance of cooling, and PETG’s preference for moderate cooling all stem from the distinct thermal and mechanical properties of these materials. Understanding these material-specific needs prevents the common mistake of assuming one cooling strategy works for everything and helps you achieve good results when working with diverse materials.

The various effects of cooling on print quality, from enabling successful overhangs and bridges to affecting layer bonding strength, reveal the trade-offs involved in cooling decisions. More cooling isn’t universally better, it improves some aspects while potentially degrading others. Learning to balance these trade-offs based on whether you’re printing aesthetic pieces where appearance matters most or functional parts where strength is paramount represents mature understanding of the printing process.

Strategic cooling adjustments for different print scenarios, from minimal first layer cooling to aggressive cooling for small features, demonstrate that effective cooling management is dynamic rather than static. Simply setting a fan speed and leaving it constant for an entire print works sometimes but optimizing cooling for specific geometries and features as they appear throughout the print produces superior results. Modern slicers provide the tools for this dynamic cooling management if you understand how to configure them.

Diagnosing cooling problems through their characteristic symptoms, whether drooping overhangs, failed bridges, warping, or brittle layer bonds, builds troubleshooting skills that apply broadly across 3D printing challenges. Many beginners struggle with these issues without recognizing them as cooling-related, trying various ineffective solutions before eventually discovering that cooling adjustment was the answer all along. Understanding cooling signatures accelerates problem resolution.

Hardware optimization through better fans, improved ducts, and proper maintenance acknowledges that software settings alone can’t overcome fundamentally inadequate cooling hardware. When stock cooling systems prove insufficient, knowing that upgrade paths exist and understanding what makes cooling systems effective empowers you to improve your printer’s capabilities. The best part is that many cooling upgrades, particularly improved ducts, can be printed on the very printer they’re meant to improve.

Looking forward, cooling will remain a critical aspect of FDM printing even as technology advances. While printers become more sophisticated with better sensors and more intelligent firmware that can automatically adjust cooling in real-time, the fundamental physics of needing to solidify molten plastic quickly remains unchanged. Understanding cooling principles ensures you can work effectively with current equipment and adapt to future innovations as they emerge.

The ultimate mastery of cooling involves knowing not just how to adjust fan speeds but understanding the physical processes at work, recognizing how cooling interacts with material properties and print geometry, and developing intuition about when cooling helps versus when it hinders. This deep understanding comes from both theoretical knowledge and practical experience, the combination of understanding why cooling matters and having printed enough to recognize its effects directly.

Cooling deserves attention as one of the core pillars of successful 3D printing, alongside extrusion control, temperature management, and motion precision. Each pillar supports print quality and success rates, and weakness in any area compromises overall results. Investing time in understanding and optimizing cooling pays dividends across all your printing projects through better results, fewer failures, and deeper comprehension of the craft of additive manufacturing. The humble cooling fan, small and often overlooked, wields outsized influence over whether your prints succeed or fail, whether they look professional or amateur, and whether they’re mechanically robust or disappointingly weak. Respect the fan, understand its purpose, optimize its operation, and you’ll be rewarded with consistently better prints.