When you begin exploring robotics, you quickly encounter two fundamentally different categories of robots that approach spatial interaction from opposite perspectives. Mobile robots move themselves through the environment—wheeled rovers exploring terrain, drones flying through air, or legged machines walking across obstacles. Manipulators, commonly called robot arms, stay fixed in place while moving objects within their workspace—industrial arms assembling products, surgical robots performing procedures, or collaborative robots working alongside humans. This division between robots that move themselves and robots that move other things represents one of the most fundamental distinctions in robotics, shaping everything from mechanical design through control algorithms to practical applications.

Understanding the mobile-versus-manipulator divide helps you make informed decisions about what type of robot to build, what skills different robot types develop, and how to think about combining both capabilities in more sophisticated systems. These two robot categories face different challenges, require different engineering approaches, and teach different aspects of robotics. A mobile robot struggling to navigate cluttered environments encounters problems completely different from a manipulator calculating precise grasping positions. Yet both are “robots,” and increasingly, advanced systems combine mobility and manipulation to achieve capabilities neither type accomplishes alone.

This article explores what fundamentally distinguishes mobile robots from manipulators, examines the unique challenges each type faces, explains what applications suit each category, and discusses how modern robotics increasingly combines both. You will learn to recognize which problems mobile robots solve well versus those requiring manipulation, understand what makes each type unique, and appreciate how the mobile-manipulator distinction structures much of robotics as a field. This framework helps you navigate robotics literature, choose appropriate starting projects, and understand how different robot types relate to each other in the broader robotics landscape.

What Defines Mobile Robots

Mobile robots fundamentally solve the problem of getting from one place to another, whether across a factory floor, through a warehouse, around your home, or across planetary surfaces. This mobility capability defines their purpose and shapes their design.

Locomotion systems provide the defining characteristic—mobile robots move themselves through space using wheels, tracks, legs, propellers, or other mechanisms. The locomotion system must overcome friction, support the robot’s weight, and generate forces propelling the robot in desired directions. Wheeled robots use rotating wheels contacting ground surfaces. Legged robots lift and place feet in walking patterns. Flying robots generate thrust overcoming gravity. The specific locomotion mechanism profoundly affects robot capabilities, appropriate terrains, and control complexity.

Navigation presents the central challenge for mobile robots—determining position, planning paths through environments, and executing motion safely avoiding obstacles. Navigation requires knowing where the robot is (localization), representing environment structure (mapping), planning routes from current position to goals (path planning), and controlling motors to follow planned paths while reacting to unexpected obstacles (motion control). These navigation tasks dominate mobile robot software development and distinguish mobile robots from manipulators.

Workspace essentially unbounded distinguishes mobile robots from manipulators’ limited reach. Mobile robots can potentially access any location they can physically reach through locomotion. A wheeled robot might explore an entire building. A drone might survey vast outdoor areas. This unlimited workspace means mobile robots can perform tasks spanning large spatial scales—surveillance, delivery, exploration—that would be impossible for stationary systems.

Environmental interaction primarily through movement means mobile robots affect the world by going places and potentially carrying payloads. Delivery robots transport packages by moving to destinations. Surveillance robots gather information by positioning sensors in various locations. Exploration robots collect samples by traveling to interesting sites. The robot’s movement itself accomplishes the task rather than moving other objects (though mobile robots can carry payloads or push objects as secondary capabilities).

Onboard power requirements constrain mobile robots more than stationary manipulators. Mobile robots must carry batteries providing energy for extended operation away from fixed power sources. Battery weight, capacity, and power consumption fundamentally limit how long mobile robots operate and what capabilities they can support. Managing power budgets and maximizing efficiency become critical concerns for mobile robot design.

Examples of mobile robots span from simple line-following robots through sophisticated autonomous vehicles. Robotic vacuum cleaners navigate homes autonomously. Warehouse robots transport inventory. Mars rovers explore planetary surfaces. Self-driving cars navigate roads. Drones inspect infrastructure. Despite vast differences in sophistication and application, all share the fundamental characteristic of locomoting through environments to accomplish tasks.

What Defines Manipulators

Manipulators approach robotics from the opposite perspective—they stay in place while moving objects or tools within their workspace. This fixed-base, mobile-end-effector architecture creates entirely different design priorities and capabilities.

Fixed base provides stable platform from which the manipulator operates. The base attaches to floor, workbench, or mounting structure, providing immovable reference point. This fixed base eliminates concerns about robot stability and falling that plague mobile robots. It also provides reliable power and communication connections—manipulators typically operate from fixed power supplies and network connections rather than batteries and wireless communication.

Articulated structure composed of rigid links connected by joints enables manipulators to reach different positions within their workspace. Each joint provides a degree of freedom, letting the arm bend, rotate, or extend in various ways. Serial manipulators chain links sequentially from base to end-effector. Parallel manipulators use multiple chains working together. The mechanical structure directly determines what positions the manipulator can reach and how forces transmit from motors to end-effector.

End-effector tools or grippers enable manipulation—the actual interaction with objects. While the arm positions and orients the end-effector, the end-effector performs the useful work: grasping objects, welding seams, painting surfaces, or performing surgery. Manipulators often feature interchangeable end-effectors, allowing the same arm to perform different tasks by swapping tools. The gripper or tool represents where robot’s capability meets the task.

Workspace limitation to volume reachable by the arm distinguishes manipulators from mobile robots’ unlimited range. A manipulator might reach points within a hemisphere of two-meter radius. Objects outside this workspace remain inaccessible no matter how the arm configures itself. This limited workspace makes positioning the manipulator crucial—the base must sit where the arm can reach all necessary locations. Applications requiring large workspace often use mobile manipulators combining mobility with manipulation.

Precision and force control matter more for manipulators than mobile robots. Manipulators performing assembly must position components within millimeters or tighter tolerances. Force control enables inserting parts that must press together with specific force. This precision requirement drives sophisticated control algorithms and precise mechanical design. Position encoders measure joint angles to fractions of degrees. Control loops run at high frequencies maintaining accurate positioning.

Kinematics calculations relating joint angles to end-effector position dominate manipulator control. Forward kinematics calculates where the end-effector sits given current joint angles. Inverse kinematics solves for joint angles achieving desired end-effector positions. These geometric calculations, often quite complex, enable manipulators to operate in Cartesian space (positioning the gripper at specific coordinates) while actually controlling joint space (commanding joint angles). The mathematics bridging these spaces is fundamental to manipulator operation.

Examples of manipulators range from simple two-joint arms in educational kits through industrial robots in manufacturing. Factory robots weld car bodies, assemble electronics, and paint products. Surgical robots perform minimally invasive procedures. Collaborative robots work alongside humans in shared workspaces. Robotic arms on spacecraft capture satellites and assemble structures. All share the characteristic fixed-base, articulated-arm architecture reaching within limited workspaces to manipulate objects or tools.

Comparing Core Challenges

The mobile-manipulator divide creates fundamentally different engineering challenges that require different skills, knowledge, and approaches to solve.

Mobile robots face navigation challenges involving localization, mapping, and path planning. Determining robot position from uncertain sensor data in partially known environments remains difficult. Building consistent maps while simultaneously localizing within those maps (SLAM – Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) presents challenging chicken-and-egg problems. Planning collision-free paths through dynamic environments with moving obstacles requires real-time computation. These navigation challenges largely do not apply to manipulators operating from known fixed positions.

Manipulators face kinematics challenges calculating joint angles from desired end-effector positions. Inverse kinematics for complex arms often has multiple solutions or no analytical solution, requiring numerical methods. Singularities where small end-effector motions require very large joint motions or where the arm loses degrees of freedom complicate control. Ensuring the arm configuration avoids collisions with itself, the base, and environment objects requires sophisticated geometric reasoning. Mobile robots rarely face analogous kinematics problems because they directly control position without joint-angle intermediation.

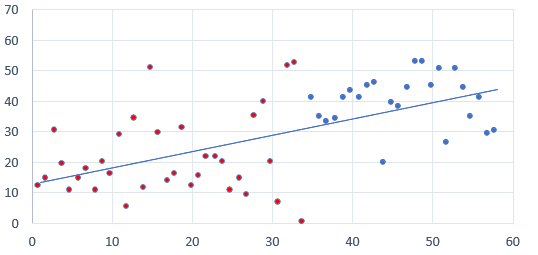

Dynamic environments challenge mobile robots more than manipulators. Mobile robots navigate spaces with moving people, vehicles, or other robots. Predicting and avoiding dynamic obstacles while making progress toward goals requires sophisticated algorithms. Manipulators typically operate in more controlled environments where obstacles remain stationary or follow known patterns (like assembly lines with repeating sequences). This difference in environmental predictability affects control complexity substantially.

Precision requirements differ dramatically. Mobile robots navigating might accept positioning errors of several centimeters. Manipulators assembling electronics might require sub-millimeter precision. This precision difference stems from task requirements—getting a delivery robot near a destination suffices, while inserting a connector demands exact alignment. The precision difference drives different sensor choices, mechanical designs, and control approaches.

Power and compute constraints affect mobile robots more than manipulators. Mobile robots must minimize power consumption to extend battery life. They carry limited computing power, restricting algorithm complexity. Manipulators with fixed power and wired network connections suffer fewer constraints. They can use powerful control computers and run complex algorithms continuously. This resource difference affects what capabilities each robot type can practically implement.

Safety considerations differ between mobile robots navigating human spaces and manipulators working near humans. Mobile robots must avoid collisions while moving. Their inertia creates impact hazards requiring obstacle detection and emergency stopping. Manipulators present different hazards—pinch points where moving arm can trap someone, crushing hazards from high forces, and collision risks from unexpected motion. Collaborative manipulators designed to work near humans require force sensing and safety-rated control preventing dangerous situations.

Learning Paths and Skill Development

Beginning with mobile robots versus manipulators develops different robotics skills and knowledge. Understanding these learning paths helps you choose appropriate starting points matching your interests.

Starting with mobile robots teaches navigation fundamentals, sensor processing, and autonomous behavior in uncertain environments. You learn coordinate systems through position tracking, control theory through motion control, and sensor fusion through combining multiple inputs for better localization. Mobile robotics emphasizes software more than precise mechanical design—getting navigation algorithms working often matters more than perfect mechanical construction. This software emphasis makes mobile robotics accessible to people with programming backgrounds but limited mechanical experience.

Starting with manipulators teaches kinematics, mechanical design, and precise control. You learn forward and inverse kinematics through calculating joint angles, structural mechanics through designing rigid linkages, and control theory through position and force control. Manipulator robotics emphasizes mechanical design and mathematical modeling more than mobile robotics does. Kinematics calculations and precise construction become unavoidable, providing deep understanding of these topics but requiring more mathematical sophistication.

Mobile robots provide faster path to seeing autonomous behavior. A simple obstacle-avoiding rover demonstrates autonomous navigation within hours of starting. The immediate feedback from robot moving around reinforces learning and provides motivation to tackle more complex challenges. This rapid progression to autonomous behavior makes mobile robotics satisfying for beginners who want to see results quickly.

Manipulators teach precision and careful engineering. Getting a robot arm to accurately reach positions requires addressing mechanical flex, encoder resolution, and control loop tuning. While this careful attention to detail requires patience, it develops rigorous engineering habits and deep understanding of precision robotics. The discipline of making manipulators work accurately transfers well to other precise robotic systems.

Both paths teach control theory but through different lenses. Mobile robots illustrate control through heading maintenance, path following, and obstacle avoidance. Manipulators teach control through position tracking, force control, and trajectory following. Experiencing control concepts in both contexts deepens understanding more than either alone provides. The control principles remain consistent but their application differs enough that both perspectives prove valuable.

Combined systems require understanding both mobility and manipulation. Mobile manipulators like robot arms mounted on mobile bases must coordinate navigation with manipulation. Learning mobile robotics then adding manipulation (or vice versa) provides natural progression toward these combined systems that represent the frontier of current robotics development.

Applications by Robot Type

Different applications naturally suit mobile robots versus manipulators based on their fundamental capabilities. Understanding these application domains helps you choose which robot type serves particular tasks.

Mobile robots excel at applications requiring coverage of large areas. Warehouse inventory management uses mobile robots carrying shelves through storage facilities. Agricultural robots patrol crop rows monitoring plant health. Security robots patrol buildings detecting intrusions. Cleaning robots traverse floors vacuuming or mopping. These applications share the characteristic that the task inherently involves going to many different locations, making mobile robots natural solutions.

Manipulators excel at fixed-location tasks requiring precise positioning and force application. Manufacturing assembly uses manipulators to position and fasten components accurately. Welding uses manipulators to move torches along seams with consistent motion. Material handling within workstations uses manipulators to pick and place items between processing stages. These applications keep the robot in one location while bringing work to the robot’s workspace.

Delivery and transportation naturally suit mobile robots. Package delivery robots navigate buildings or sidewalks carrying items to destinations. Hospital robots transport medications, linens, or meals between locations. Mining and construction sites use autonomous vehicles transporting materials. The task fundamentally involves moving objects by moving the robot carrying them, making mobility essential.

Precision assembly and processing suit manipulators. Electronics assembly requiring precise component placement uses manipulators with fine positioning capabilities. CNC machining alternatives using robotic arms provide flexible manufacturing. 3D printing scaled to large sizes uses robot arms as positioning systems. These applications require accuracy that mobile platforms struggle to achieve while keeping robots in controlled workspaces where manipulators operate naturally.

Inspection at height or in difficult access locations uses mobile robots including flying drones or climbing robots. Bridge inspection, wind turbine examination, and building facade surveys use drones positioning cameras and sensors. Pipeline inspection uses mobile robots traversing confined spaces. The mobility enables reaching inspection locations inaccessible to fixed manipulators.

Delicate manipulation of dangerous materials suits manipulators. Handling hazardous chemicals, radioactive materials, or explosives keeps human operators safely distant while manipulators perform necessary operations. Bomb disposal uses manipulators to examine and disarm explosive devices. Nuclear facility decommissioning uses manipulators to cut and remove contaminated equipment. The manipulator’s ability to apply precise force safely from a distance suits these applications.

The Rise of Mobile Manipulators

Increasingly, robotics moves beyond the mobile-versus-manipulator divide toward integrated systems combining both capabilities. Mobile manipulators represent significant current development area addressing applications requiring both mobility and manipulation.

Mobile bases provide manipulators with unlimited workspace by moving the base to wherever manipulation is needed. Rather than installing fixed manipulators in every location where manipulation might occur, a single mobile manipulator moves between locations as needed. This mobility dramatically expands the effective workspace while maintaining manipulation precision when stationed at work locations. Warehouse robots that both transport shelves and pick items from them exemplify this combination.

Manipulation enables mobile robots to interact with environments beyond just navigating through them. A mobile robot that can open doors, press elevator buttons, or move obstacles expands its accessible environment beyond spaces specifically designed for robot navigation. Household robots combining mobility with manipulation can perform diverse tasks in human environments not modified for robots.

Coordination challenges between mobility and manipulation create interesting control problems. Should the mobile base move while the arm manipulates, or should the base remain stationary during manipulation? How do navigation algorithms account for arm configuration affecting robot dimensions and center of mass? These coordination questions require treating the combined system holistically rather than as separate mobile and manipulation components.

Applications uniquely enabled by mobile manipulation include flexible manufacturing where robots move between workstations performing different tasks, hospital assistance robots that navigate to patients and manipulate medical equipment, and domestic assistance robots that fetch items from various locations. These applications would be impossible or impractical with pure mobility or pure manipulation alone.

Current research actively develops mobile manipulator capabilities. Whole-body motion planning coordinates mobile base and manipulator arm motion simultaneously. Visual servoing uses cameras to guide manipulation while allowing base motion. Learning-based approaches teach mobile manipulators complex tasks through demonstration or trial-and-error. These advances push toward general-purpose robots that move through environments and manipulate objects flexibly.

Choosing Your Robot Type

For someone starting in robotics, deciding whether to begin with mobile robots, manipulators, or combined systems depends on interests, goals, and resources.

Choose mobile robots if you are interested in navigation, autonomy, and software-heavy robotics. Mobile robots reward programming skills and algorithmic thinking more than mechanical precision. The rapid path to autonomous behavior provides motivation and demonstrates concepts quickly. Mobile robots suit people with software backgrounds or those more interested in intelligence and autonomy than mechanical precision.

Choose manipulators if you are interested in kinematics, mechanical design, and precision control. Manipulators reward careful mechanical construction and mathematical modeling. The precise positioning requirements develop discipline and engineering rigor. Manipulators suit people with mechanical aptitude or those interested in the mathematics relating joint angles to spatial positions.

Start with simple versions of either type to build foundations before tackling complex systems. A basic wheeled rover teaches mobile robot concepts. A simple two-joint arm teaches manipulator kinematics. These simplified systems let you learn fundamentals without the overwhelming complexity of professional systems. As skills develop, you can progress to more sophisticated versions of whichever type interests you.

Consider application goals when choosing robot type. If you want to build robots performing tasks in your home, mobile robots for cleaning or delivery might interest you more than manipulators. If you are interested in manufacturing or assembly, manipulators provide relevant experience. Matching robot type to eventual application goals makes learning more motivated and ensures developed skills apply to your intended domain.

Educational value differs between types but neither is superior. Mobile robots teach different aspects of robotics than manipulators, but both teach valuable concepts. Experiencing both types eventually provides comprehensive robotics education. However, starting with the type that matches your interests keeps you engaged through the initial learning curve. You can always explore the other type once you have foundations in one area.

Resources and space constraints might influence choices. Mobile robots need floor space to move around. Manipulators need vertical space and secure mounting but less floor area. Budget-wise, basic mobile robots can be slightly cheaper than manipulators, though both are accessible to hobbyists. Consider your available workspace and budget when choosing which type to pursue first.

Beyond the Divide: Integrated Robotics

While the mobile-versus-manipulator distinction helps organize thinking about robot types, robotics increasingly transcends this categorization. Modern systems often combine multiple capabilities that blur traditional boundaries.

Humanoid robots combine locomotion with dual-arm manipulation, attempting to recreate the full range of human physical capabilities. These systems face challenges from both mobile robotics (bipedal locomotion being exceptionally difficult) and manipulation (coordinating two arms for bimanual tasks). Humanoids represent the extreme of integrated systems that defy simple categorization as mobile or manipulator.

Soft robots using compliant materials and continuous deformation challenge the rigid-body assumptions underlying traditional mobile and manipulator robotics. A soft robot might locomote through peristaltic motion while simultaneously conforming to grasp irregular objects. The soft robotics approach transcends the mobile-manipulator divide by achieving both through fundamentally different mechanisms than either traditional category uses.

Swarm robotics with many simple robots working cooperatively creates collective capabilities no individual robot possesses. Swarms of mobile robots might cooperatively manipulate large objects, combining mobility from individual units with emergent manipulation capability from the group. This distributed approach to achieving both mobility and manipulation differs from single-robot solutions.

Reconfigurable robots that change their morphology adapt to different tasks, potentially switching between mobile and manipulator configurations. A modular robot might configure as a mobile platform for navigation then reconfigure as a manipulator structure for assembly tasks. These shape-shifting systems explicitly embrace both robot types within single hardware platform.

The fundamental mobile-versus-manipulator distinction remains useful for understanding current robotics and organizing learning, but the field constantly pushes beyond these categories toward more integrated, flexible, and capable systems. Understanding both mobile robots and manipulators provides foundation for appreciating and eventually contributing to these advanced integrated systems that represent robotics’ future directions.

Conclusion: Two Sides of the Robotics Coin

Mobile robots and manipulators represent complementary approaches to robotic spatial interaction. Mobile robots move themselves to accomplish tasks across large areas. Manipulators stay fixed while precisely positioning tools and objects within limited workspaces. These different approaches solve different problems, require different engineering approaches, and teach different aspects of robotics.

Understanding this fundamental divide helps you navigate robotics as a field, choose appropriate learning paths, and recognize which robot type suits particular applications. Neither mobile robots nor manipulators are universally superior—each excels in their domain. The question is not which type is better but which type suits your interests, goals, and the problems you want to solve.

As you progress in robotics, you will likely encounter both mobile robots and manipulators. The skills learned working with one type transfer partially to the other—control theory, programming, sensor processing all apply to both. Yet each type has unique characteristics and challenges that make experiencing both valuable for comprehensive robotics education.

The future of robotics increasingly combines mobility and manipulation in integrated systems achieving capabilities neither type provides alone. However, understanding mobile robots and manipulators separately provides essential foundation for appreciating and working with these combined systems. The mobile-manipulator divide structures much of robotics education, research, and industry even as the field works to transcend it.

Whether you begin with mobile robots or manipulators, you embark on learning fundamental robotics concepts that apply throughout the field. The specific robot type provides context and concrete problems, but the underlying principles—sensing, control, kinematics, planning—transcend the mobile-manipulator distinction. Your journey starts with one type but need not end there. Both mobile robots and manipulators await your exploration, each offering unique insights into how machines can interact with and operate in physical space.