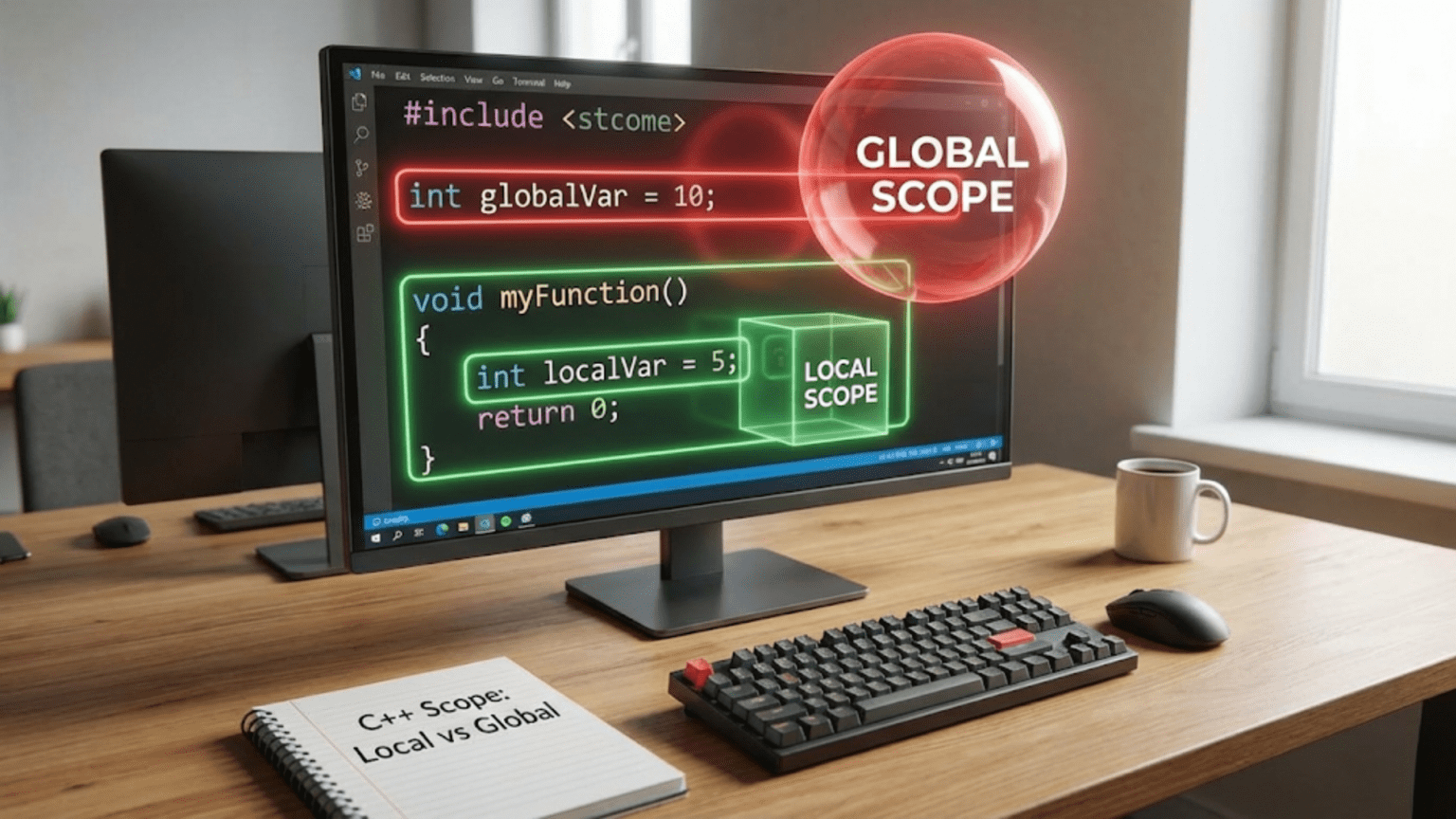

When you declare a variable in your program, you might wonder: where can I use this variable? Can I access it from any function, or only from specific places? What happens if I create two variables with the same name in different parts of my program? These questions all relate to scope—the region of code where a variable exists and can be accessed. Understanding scope is fundamental to writing correct C++ programs because scope determines variable lifetime, visibility, and prevents naming conflicts. Variables declared in different scopes are completely separate even if they share names, and accessing a variable outside its scope causes compilation errors. Mastering scope transforms you from someone who accidentally creates bugs through variable naming conflicts to someone who deliberately structures code to prevent such problems.

Think of scope like rooms in a building. A note you leave on a desk in your office is accessible to anyone in that office, but people in other offices can’t see it without entering your office. Similarly, variables declared inside a function are accessible within that function but invisible to other functions. The building itself has a lobby where notices posted there can be seen by everyone entering any office—these are like global variables accessible throughout the program. Just as buildings can have rooms within rooms (a closet inside an office), C++ has nested scopes where variables in outer scopes remain accessible in inner scopes unless shadowed by local declarations.

The power of scope comes from enabling modularity and preventing conflicts. When you write a function, you can freely choose variable names without worrying about whether those names are used elsewhere in the program, because your function’s local variables are invisible outside the function. This isolation enables building large programs from independently-written components without constant coordination about variable names. Understanding scope deeply enables writing cleaner code where variables exist only where they’re needed, making programs easier to understand and maintain while preventing entire categories of bugs related to unintended variable access.

Let me start by showing you the most fundamental scope distinction—local variables that exist only within functions versus global variables accessible throughout the program:

#include <iostream>

// Global variable - accessible from anywhere in this file

int globalCounter = 0;

void incrementGlobal() {

// Can access global variable

globalCounter++;

std::cout << "Global counter incremented to: " << globalCounter << std::endl;

}

void demonstrateLocal() {

// Local variable - exists only within this function

int localValue = 42;

std::cout << "Local value: " << localValue << std::endl;

// Can also access global variable

std::cout << "Global counter: " << globalCounter << std::endl;

}

void anotherFunction() {

// Cannot access localValue from demonstrateLocal

// std::cout << localValue << std::endl; // Compilation error!

// Can access global variable

std::cout << "Global counter in another function: " << globalCounter << std::endl;

}

int main() {

std::cout << "Initial global counter: " << globalCounter << std::endl;

incrementGlobal();

incrementGlobal();

demonstrateLocal();

anotherFunction();

// Cannot access localValue from main

// std::cout << localValue << std::endl; // Compilation error!

return 0;

}This example demonstrates the fundamental distinction between local and global scope. The globalCounter variable declared outside all functions has global scope, making it accessible from any function in the file. The localValue variable declared inside demonstrateLocal has local scope—it exists only while that function executes and is invisible to other functions. Attempting to access localValue from main or anotherFunction causes compilation errors because the variable simply doesn’t exist in those contexts.

Block scope applies to variables declared within any pair of curly braces, creating nested scopes within functions:

#include <iostream>

void demonstrateBlockScope() {

int outer = 10;

std::cout << "Outer variable: " << outer << std::endl;

{

// Inner block - creates new scope

int inner = 20;

std::cout << "Inner variable: " << inner << std::endl;

std::cout << "Can access outer from inner: " << outer << std::endl;

// Can modify outer variable from inner scope

outer = 15;

} // inner goes out of scope and is destroyed here

std::cout << "Outer after inner block: " << outer << std::endl;

// Cannot access inner here - it no longer exists

// std::cout << inner << std::endl; // Compilation error!

}

void demonstrateControlStructureScope() {

// Variables in for loop have block scope

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

std::cout << "Loop iteration: " << i << std::endl;

}

// i doesn't exist here

// std::cout << i << std::endl; // Compilation error!

// Variables in if statements have block scope

if (true) {

int ifVar = 100;

std::cout << "Inside if: " << ifVar << std::endl;

}

// ifVar doesn't exist here

// std::cout << ifVar << std::endl; // Compilation error!

// Each iteration of a loop gets its own scope

for (int j = 0; j < 2; j++) {

int loopVar = j * 10;

std::cout << "Loop var: " << loopVar << std::endl;

} // loopVar destroyed at end of each iteration

}

int main() {

demonstrateBlockScope();

std::cout << std::endl;

demonstrateControlStructureScope();

return 0;

}Block scope means variables exist from their declaration until the closing brace of the block that contains them. Variables in outer scopes remain accessible in inner scopes, but inner scope variables are invisible to outer scopes. The for loop variable i has scope limited to the loop itself—it exists during loop execution but is destroyed when the loop ends. This scoping prevents the common bug of reusing loop variables and ensures variables don’t outlive their usefulness.

Variable shadowing occurs when a variable in an inner scope has the same name as a variable in an outer scope, hiding the outer variable:

#include <iostream>

int value = 100; // Global variable

void demonstrateShadowing() {

int value = 50; // Local variable shadows global

std::cout << "Local value: " << value << std::endl; // Prints 50

// To access global variable, use scope resolution operator

std::cout << "Global value: " << ::value << std::endl; // Prints 100

{

int value = 25; // Inner block variable shadows both outer scopes

std::cout << "Inner block value: " << value << std::endl; // Prints 25

}

std::cout << "After inner block: " << value << std::endl; // Prints 50

}

void demonstrateParameterShadowing(int value) {

// Parameter 'value' shadows global variable

std::cout << "Parameter value: " << value << std::endl;

// Access global using ::

std::cout << "Global value: " << ::value << std::endl;

}

int main() {

demonstrateShadowing();

std::cout << std::endl;

demonstrateParameterShadowing(75);

return 0;

}When a local variable has the same name as a global variable, the local variable shadows the global, making the global inaccessible by simple name within that scope. The scope resolution operator :: allows accessing the global variable explicitly—::value refers specifically to the global variable regardless of local variables with the same name. While shadowing is legal, it often causes confusion and is generally best avoided by using distinct names for variables in different scopes.

Let me show you a practical example demonstrating how scope enables clean separation of concerns in real programs:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

// Global configuration - acceptable for truly global settings

const int MAX_PLAYERS = 4;

const std::string GAME_TITLE = "Scope Adventure";

// Poor practice - global mutable state

// int playerScore = 0; // Avoid this!

class Player {

private:

std::string name;

int score;

int health;

public:

Player(const std::string& playerName)

: name(playerName), score(0), health(100) {}

void addScore(int points) {

// 'points' parameter has function scope

// 'score' member has class scope

score += points;

// Local variable for message

std::string message = name + " gained " + std::to_string(points) + " points";

std::cout << message << std::endl;

// Temporary calculation variable - block scope

{

int bonus = points / 10;

if (bonus > 0) {

score += bonus;

std::cout << "Bonus: " << bonus << " points!" << std::endl;

}

} // bonus destroyed here

}

void takeDamage(int damage) {

health -= damage;

if (health <= 0) {

health = 0;

std::cout << name << " has been defeated!" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << name << " took " << damage << " damage. Health: "

<< health << std::endl;

}

}

void displayStatus() const {

// Local variables just for display formatting

std::string healthBar = "[";

int healthPercent = health;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

healthBar += (i < healthPercent / 10) ? "#" : "-";

}

healthBar += "]";

std::cout << "\n=== " << name << " ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Score: " << score << std::endl;

std::cout << "Health: " << healthBar << " (" << health << "%)" << std::endl;

}

std::string getName() const { return name; }

bool isAlive() const { return health > 0; }

};

class Game {

private:

std::vector<Player> players;

int currentRound;

public:

Game() : currentRound(0) {}

void addPlayer(const std::string& name) {

if (players.size() < MAX_PLAYERS) { // Access global constant

players.push_back(Player(name));

std::cout << "Player added: " << name << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Maximum players reached!" << std::endl;

}

}

void playRound() {

currentRound++;

std::cout << "\n=== Round " << currentRound << " ===" << std::endl;

// Loop variable 'i' has for-loop scope

for (size_t i = 0; i < players.size(); i++) {

// Calculate points for this round - local to loop iteration

int roundPoints = (i + 1) * 10 * currentRound;

players[i].addScore(roundPoints);

// Simulate damage - local variable

if (currentRound > 2) {

int damage = 15;

players[i].takeDamage(damage);

}

}

// Display all player statuses

for (auto& player : players) {

player.displayStatus();

}

}

void displayTitle() const {

// Local formatting variables

std::string border(GAME_TITLE.length() + 4, '=');

std::cout << "\n" << border << std::endl;

std::cout << " " << GAME_TITLE << std::endl; // Access global constant

std::cout << border << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

// Variables local to main

Game game;

game.displayTitle();

// Add players - these strings are local to main

std::string player1 = "Alice";

std::string player2 = "Bob";

std::string player3 = "Carol";

game.addPlayer(player1);

game.addPlayer(player2);

game.addPlayer(player3);

// Play multiple rounds

for (int round = 0; round < 3; round++) {

game.playRound();

}

std::cout << "\nGame completed!" << std::endl;

return 0;

}This game example demonstrates proper scope usage at multiple levels. Global constants like MAX_PLAYERS and GAME_TITLE have file scope because they’re truly global configuration. Each class has its own member scope where member variables are accessible to all member functions. Within member functions, local variables exist only for the function’s duration. Loop variables exist only during loop execution. Temporary variables in inner blocks exist only within those blocks. This layered scoping keeps each variable’s visibility limited to where it’s needed, preventing accidental misuse and making the code easier to understand.

The lifetime of variables directly relates to their scope—local variables are created when execution reaches their declaration and destroyed when execution leaves their scope:

#include <iostream>

class Resource {

private:

std::string name;

public:

Resource(const std::string& n) : name(n) {

std::cout << "Resource created: " << name << std::endl;

}

~Resource() {

std::cout << "Resource destroyed: " << name << std::endl;

}

void use() {

std::cout << "Using resource: " << name << std::endl;

}

};

void demonstrateLifetime() {

std::cout << "Function started" << std::endl;

Resource r1("Function-scope");

r1.use();

{

std::cout << "Entering inner block" << std::endl;

Resource r2("Block-scope");

r2.use();

std::cout << "Exiting inner block" << std::endl;

} // r2 destroyed here

std::cout << "After inner block" << std::endl;

r1.use();

std::cout << "Function ending" << std::endl;

} // r1 destroyed here

Resource globalResource("Global"); // Created before main

int main() {

std::cout << "Main started" << std::endl;

globalResource.use();

demonstrateLifetime();

std::cout << "Main ending" << std::endl;

globalResource.use();

return 0;

} // globalResource destroyed after main returnsThe output from this program clearly shows when objects are created and destroyed based on scope. The global resource is created before main runs and destroyed after main returns. Function-local resources are created when the function executes and destroyed when it returns. Block-local resources are created when execution enters the block and destroyed when leaving the block. This automatic lifetime management based on scope is fundamental to RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization), a core C++ idiom.

Namespace scope provides another level of organization beyond global scope, preventing naming conflicts in large programs:

#include <iostream>

// Global scope

int value = 100;

// Namespace scope

namespace Math {

int value = 200; // Different from global value

double square(double x) {

return x * x;

}

}

namespace Graphics {

int value = 300; // Different from both global and Math::value

void drawPoint(int x, int y) {

std::cout << "Drawing point at (" << x << ", " << y << ")" << std::endl;

}

}

void demonstrateNamespaceScope() {

std::cout << "Global value: " << ::value << std::endl;

std::cout << "Math::value: " << Math::value << std::endl;

std::cout << "Graphics::value: " << Graphics::value << std::endl;

// Use namespace functions

std::cout << "Square of 5: " << Math::square(5) << std::endl;

Graphics::drawPoint(10, 20);

}

int main() {

demonstrateNamespaceScope();

// Using declaration - brings specific name into current scope

using Math::square;

std::cout << "Square of 7: " << square(7) << std::endl;

// Using directive - brings all names from namespace into scope

using namespace Graphics;

drawPoint(30, 40);

return 0;

}Namespaces create separate scope regions where names can be reused without conflict. The value variable exists independently in global scope, Math namespace, and Graphics namespace. Accessing namespace members requires qualification with the namespace name unless you use a using declaration or directive. Namespaces are essential for organizing large codebases and preventing naming conflicts between libraries.

Static variables at function scope have interesting properties—they maintain their values between function calls:

#include <iostream>

void countCalls() {

static int callCount = 0; // Initialized only once, persists between calls

callCount++;

std::cout << "This function has been called " << callCount << " times" << std::endl;

}

int generateID() {

static int nextID = 1000;

return nextID++;

}

void demonstrateStaticLocal() {

static bool firstTime = true;

if (firstTime) {

std::cout << "First time calling this function" << std::endl;

firstTime = false;

} else {

std::cout << "Called this function before" << std::endl;

}

}

int main() {

// Call countCalls multiple times

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

countCalls();

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// Generate multiple IDs

std::cout << "ID 1: " << generateID() << std::endl;

std::cout << "ID 2: " << generateID() << std::endl;

std::cout << "ID 3: " << generateID() << std::endl;

std::cout << std::endl;

// Demonstrate initialization check

demonstrateStaticLocal();

demonstrateStaticLocal();

demonstrateStaticLocal();

return 0;

}Static local variables combine local scope visibility with global lifetime. They’re accessible only within their function but persist between function calls, maintaining their values. The static keyword causes initialization to occur only once, the first time execution reaches the declaration. Subsequent calls skip the initialization. This pattern is useful for counters, caches, and one-time initialization flags.

Understanding scope rules helps avoid common bugs and write cleaner code. Variables should have the smallest scope necessary for their purpose—if a variable is only needed within a loop, declare it in the loop. If only needed in one function, make it local to that function. This principle of minimal scope makes code easier to understand and maintains because you can see all uses of a variable within a limited region.

Common mistakes with scope include declaring variables with broader scope than necessary, creating naming conflicts through shadowing, attempting to access variables outside their scope, and forgetting that variables are destroyed when leaving their scope. Another subtle error is depending on the order of initialization for global variables across different source files, which is undefined in C++.

Key Takeaways

Variable scope determines where in your program a variable can be accessed and how long it exists. Local variables declared within functions or blocks have scope limited to that function or block and are destroyed when execution leaves their scope. Global variables declared outside all functions have scope throughout the file and exist for the program’s entire execution. Block scope applies to variables declared within any curly braces, including loops and if statements, with the variable existing from declaration to the closing brace.

Variable shadowing occurs when an inner scope declares a variable with the same name as an outer scope variable, hiding the outer variable within the inner scope. The scope resolution operator :: allows accessing global variables even when shadowed by local variables. While legal, shadowing often causes confusion and should generally be avoided by using distinct names.

Variable lifetime directly relates to scope—local variables are created at their declaration and destroyed when leaving their scope, while global variables exist for the program’s entire execution. Namespaces provide organized scope regions that prevent naming conflicts, particularly important in large programs and libraries. Static local variables combine local scope with global lifetime, persisting between function calls while remaining accessible only within their function. Understanding scope enables writing modular code where variables exist only where needed, improving clarity and preventing entire categories of bugs related to unintended variable access.