The Illusion of Unlimited Memory

When you open multiple applications simultaneously on your computer—perhaps a web browser with dozens of tabs, a word processor, a spreadsheet, an email client, and a music player—you might be using more memory than physically exists in your system. This isn’t magic or impossible; it’s the result of a sophisticated technique called virtual memory that creates the illusion of having far more RAM than actually installed. Virtual memory represents one of the most ingenious solutions in computer science, allowing operating systems to overcome hardware limitations while maintaining the abstraction that each program has access to vast amounts of memory. Understanding how virtual memory works reveals fundamental principles of operating system design and explains various behaviors you might observe when your computer starts running low on physical memory.

Physical RAM (Random Access Memory) represents the fast, temporary storage where your computer keeps data that programs are actively using. When you open a program, it loads into RAM. When you edit a document, your changes exist in RAM until saved to disk. RAM is dramatically faster than permanent storage like hard drives or SSDs—accessing data in RAM takes nanoseconds while accessing disk takes milliseconds, a difference of roughly a million times. This speed makes RAM essential for good performance, but RAM has significant limitations: it’s expensive relative to storage, typical computers have limited amounts (perhaps 8, 16, or 32 gigabytes), and it loses all contents when power is removed.

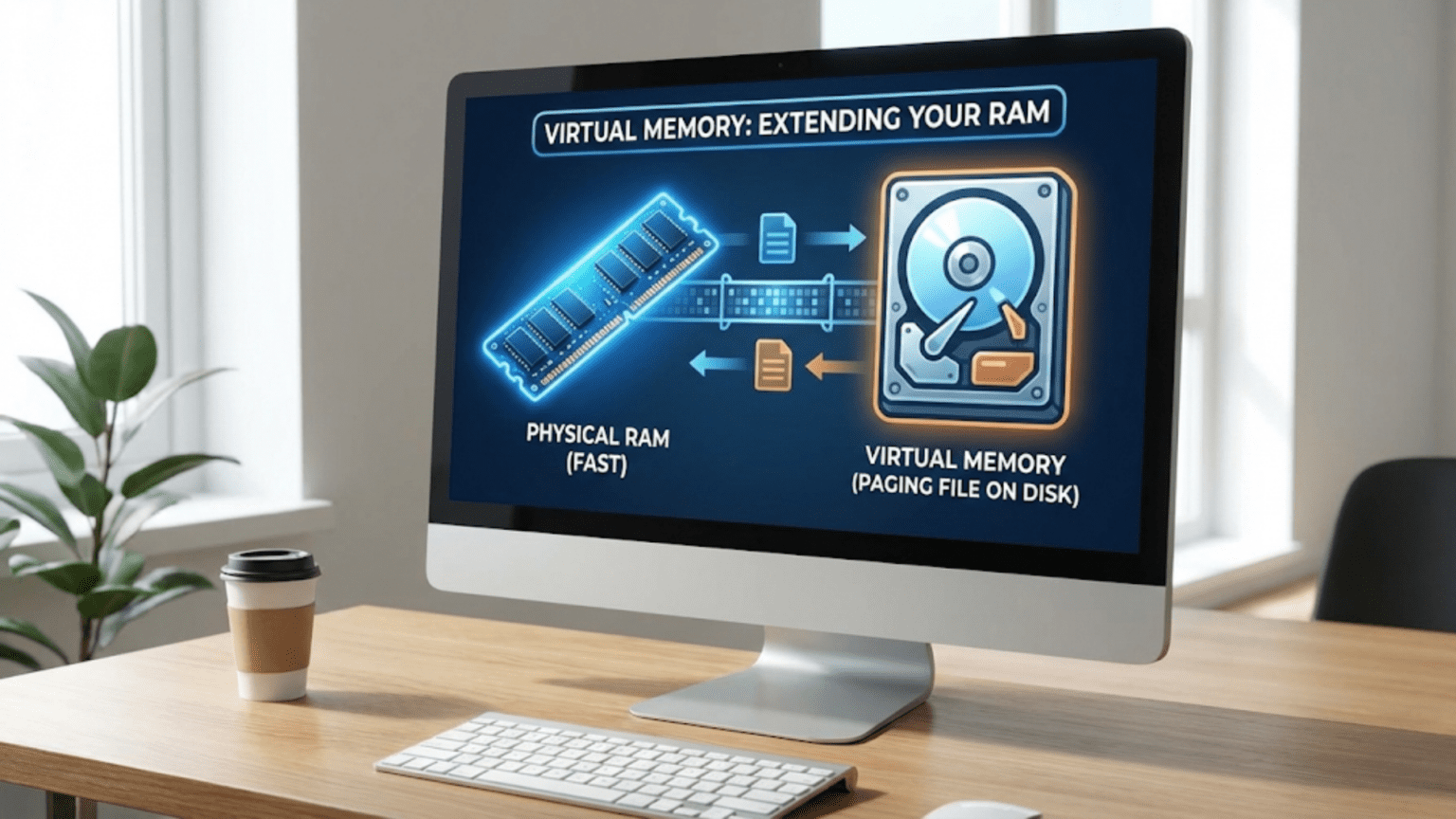

Virtual memory solves the capacity limitation by using disk space as an extension of physical RAM. When physical memory fills up, the operating system can temporarily move some data from RAM to a reserved area on the disk, freeing physical memory for other uses. This reserved disk area goes by various names—swap space on Linux, page file on Windows, swap file on macOS—but the concept remains the same: using slow but abundant disk storage to supplement fast but limited physical memory. The operating system manages this transparently, moving data between RAM and disk automatically based on what programs need. From each program’s perspective, memory appears abundant and always available, even though the operating system is constantly juggling what actually resides in physical RAM versus what’s temporarily stored on disk.

The Fundamentals: How Virtual Memory Works

Virtual memory creates an abstraction layer between the memory addresses that programs use and the physical memory addresses where data actually resides. This abstraction enables the operating system to provide each program with its own isolated address space while efficiently sharing limited physical memory among all running programs.

Every program uses virtual addresses—memory locations from the program’s perspective that may or may not correspond to actual physical memory. When a program wants to read or write data at a virtual address, the operating system’s memory management unit (MMU) translates that virtual address to a physical address in RAM. This translation happens through page tables, data structures that map virtual addresses to physical addresses. The page table is essentially a lookup table: given a virtual address, it tells you which physical address contains that data, or indicates that the data isn’t currently in physical memory.

Memory is divided into fixed-size chunks called pages, typically 4 kilobytes each. This page-based organization simplifies memory management because the operating system works with uniform blocks rather than arbitrary-sized memory regions. When a program allocates memory, the operating system assigns whole pages to that program. The page table tracks which virtual pages map to which physical pages, and which pages aren’t currently in physical memory.

The translation from virtual to physical addresses happens for every memory access, which sounds expensive but is optimized through hardware and caching. The MMU, built into modern processors, performs translations in hardware, making the process extremely fast. A Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) caches recent address translations, allowing most memory accesses to translate without consulting the full page table. These optimizations make virtual memory efficient enough that the abstraction layer adds minimal overhead to memory operations.

Each running process has its own page table, creating isolated virtual address spaces. Two different programs can both use virtual address 0x10000000, but these addresses map to different physical pages, preventing programs from interfering with each other’s memory. This isolation provides both security—programs can’t read other programs’ data—and stability—bugs in one program can’t corrupt another program’s memory. The operating system enforces these boundaries through the MMU, which only translates addresses according to the current process’s page table.

Paging: Moving Data Between RAM and Disk

The most critical aspect of virtual memory is paging—the mechanism that moves data between physical RAM and disk storage to create the illusion of abundant memory.

When physical memory becomes scarce, the operating system must decide which pages to move from RAM to disk. This decision is made by a page replacement algorithm, which tries to identify pages that won’t be needed soon, making them good candidates for temporary storage on disk. The operating system marks these pages in the page table as not present in physical memory, writes their contents to the page file on disk, and reclaims the physical memory for other uses.

Later, when a program tries to access data that’s been moved to disk, a page fault occurs. A page fault is an exception that happens when the program tries to access a virtual address whose page isn’t currently in physical RAM. The processor detects this condition—the page table indicates the page is not present—and triggers the page fault handler in the operating system kernel. The page fault handler locates the data on disk, reads it back into a physical page of RAM, updates the page table to reflect the new physical location, and allows the program to continue. This entire process is transparent to the program, which simply experiences a delay while its memory access completes.

Page faults are expensive operations because disk access is slow compared to RAM. Reading a page from even a fast SSD takes milliseconds—thousands of times longer than accessing RAM. When page faults occur frequently, the system experiences thrashing, where it spends more time moving pages between RAM and disk than actually executing useful program instructions. Thrashing causes severe performance degradation, with the system feeling sluggish and unresponsive as it constantly retrieves pages from disk. This is why adequate physical memory is so important—virtual memory extends your capacity, but it cannot match the performance of actual RAM.

The operating system employs various strategies to minimize page faults and their performance impact. Prefetching anticipates which pages programs will need next and loads them proactively before page faults occur. Clustering writes multiple pages to disk in a single operation rather than many small writes, improving efficiency. Page fault handling is optimized to be as fast as possible, using efficient disk I/O and minimizing time spent in kernel code. Despite these optimizations, excessive paging still causes noticeable performance problems.

Page Replacement Algorithms: Choosing What to Evict

When physical memory fills and the system needs to free space, the page replacement algorithm determines which pages to move to disk. Different algorithms make different trade-offs between simplicity, effectiveness, and overhead.

The optimal algorithm would evict pages that won’t be needed for the longest time, but this requires knowing the future, which is impossible. Instead, practical algorithms use various heuristics to approximate optimal behavior.

First-In-First-Out (FIFO) evicts the oldest pages in memory, based on the assumption that pages loaded long ago are less likely to be needed soon. FIFO is simple to implement—maintain a queue of pages in the order they were loaded—but it performs poorly because age doesn’t reliably predict future use. A page loaded early might still be frequently accessed, but FIFO would evict it simply because it’s old.

Least Recently Used (LRU) evicts pages that haven’t been accessed recently, based on the assumption that pages used recently will likely be used again soon (temporal locality). LRU performs much better than FIFO because recent access is a strong predictor of future access. However, true LRU is expensive to implement—tracking exact access times for every page requires hardware support that isn’t always available. Many systems approximate LRU using various techniques that provide similar benefits with lower overhead.

Clock (also called Second Chance) approximates LRU efficiently using a referenced bit that hardware sets when a page is accessed. The algorithm maintains a circular list of pages with a “hand” pointing to the next candidate for eviction. When a page is needed, the hand sweeps around the list. If a page’s referenced bit is set, the algorithm clears it and moves to the next page. If the referenced bit is clear, that page hasn’t been accessed since the last sweep and becomes the eviction candidate. This approximation is efficient and performs reasonably well in practice.

Not Recently Used (NRU) uses both referenced and modified bits to classify pages into four categories: not referenced and not modified (best eviction candidate), referenced but not modified, not referenced but modified (strange but possible), and referenced and modified (worst eviction candidate). The algorithm evicts from the lowest category that contains pages. This simple classification provides better decisions than pure FIFO while remaining computationally cheap.

Working Set algorithms track the set of pages each process has accessed recently—its working set—and try to keep these pages in memory. If a process’s working set doesn’t fit in available memory, the algorithm might suspend that process entirely rather than causing continuous page faults. This approach acknowledges that some processes need a minimum amount of memory to run effectively.

Modern operating systems often use combinations of these algorithms, applying different strategies based on page types. File-backed pages that can be reread from disk might use different policies than anonymous pages that must be written to swap space. The system might treat pages differently based on whether they’re shared between processes, contain executable code, or hold application data.

The Benefits of Virtual Memory

Virtual memory provides several crucial benefits that make it fundamental to modern operating systems, despite the performance costs when physical memory is insufficient.

Memory isolation between processes creates security and stability. Each process has its own virtual address space, unable to access memory belonging to other processes. This isolation prevents malicious programs from reading sensitive data in other processes and prevents buggy programs from corrupting others’ memory. Without virtual memory, programs would share a single physical address space, and any program could access any memory, making systems vulnerable to both accidents and attacks.

Simplified programming results from each process seeing a consistent virtual address space. Programs don’t need to worry about where their memory physically resides or what other programs are using. They can allocate memory at predictable virtual addresses without conflicts. This abstraction makes programming easier and more reliable because memory management complexity is hidden behind the virtual memory interface.

Efficient memory sharing enables multiple processes to share the same physical memory for common code or data. When multiple instances of a program run simultaneously, they can share the same physical pages containing the program’s executable code, saving memory. Similarly, shared libraries load once into physical memory and map into multiple processes’ virtual address spaces. This sharing dramatically reduces total memory consumption for systems running many processes, though each process sees its own virtual copy.

Demand paging allows running programs larger than physical RAM. Without virtual memory, programs would be limited to available physical memory size. Virtual memory enables large applications to run on systems with modest RAM by keeping only actively used portions in physical memory while storing unused portions on disk. While performance suffers when active portions exceed physical memory, at least the program can run, whereas without virtual memory it couldn’t run at all.

Memory overcommitment lets the operating system allocate more virtual memory than physical memory exists. Many programs allocate memory they never actually use, reserving space “just in case.” Virtual memory accommodates this overcommitment because pages are only backed by physical memory or disk space when actually accessed. Unused allocations consume no resources beyond page table entries. This overcommitment allows running more programs simultaneously than would fit if every allocation required immediate physical backing.

Swap Space: The Disk Extension of RAM

The swap space (or page file) represents the disk area where pages evicted from physical memory are stored. Understanding how this space is configured and managed helps optimize system behavior.

On Windows, the page file typically resides at C:\pagefile.sys, a hidden system file that the operating system manages automatically. Windows can adjust the page file size dynamically based on demand, growing it when more swap space is needed and potentially shrinking it when demand decreases. Users can manually configure page file location and size, sometimes placing it on faster drives for better performance or setting fixed sizes to prevent fragmentation.

Linux systems traditionally use dedicated swap partitions—entire disk partitions reserved exclusively for paging. The advantage is that dedicated partitions avoid filesystem overhead and fragmentation. However, modern Linux also supports swap files, which are regular files in the filesystem designated for swap use. Swap files provide more flexibility because they don’t require repartitioning and can be resized more easily than partitions.

macOS uses dynamic swap files that the system creates as needed and removes when demand decreases. Rather than a single large swap file, macOS might create multiple smaller files in /var/vm/, growing and shrinking swap capacity automatically. This approach provides flexibility without requiring user configuration.

Swap space sizing guidelines traditionally suggested swap should equal physical RAM size or twice RAM size, but modern recommendations are more nuanced. Systems with abundant RAM might need little swap space because they rarely page. Systems with limited RAM benefit from more swap space, though excessive swap won’t compensate for insufficient physical memory—it just allows more thrashing. A reasonable modern guideline might be: for systems with 8GB or less RAM, swap equal to RAM size; for larger systems, swap can be smaller or even minimal if hibernation isn’t needed.

Swap space location affects performance significantly. Placing swap on fast SSDs improves paging performance compared to slow hard drives, though SSD wear from frequent writes becomes a consideration. Some systems support swap on multiple devices, using faster devices first and slower ones only when necessary. RAID configurations for swap can provide better throughput, though the benefit is limited because the goal is avoiding swap use entirely.

Encryption considerations for swap space are important because swap contains copies of data from RAM, which might include sensitive information like passwords or encryption keys. Some operating systems support encrypted swap, ensuring that even if someone gains physical access to the disk, they cannot read swap contents without decryption keys. Encrypted swap typically uses session keys that are lost on reboot, providing security while avoiding the complication of permanent swap encryption keys.

Performance Implications and Monitoring

Understanding virtual memory’s performance impact helps diagnose slowdowns and guides optimization efforts.

Memory pressure describes how close the system is to running out of physical memory. Low memory pressure means abundant free RAM, and the system rarely pages. High memory pressure indicates limited free memory, with frequent paging and potential performance problems. Operating systems monitor memory pressure and adjust behavior accordingly—becoming more aggressive about reclaiming memory, deferring low-priority operations, or warning users about insufficient memory.

Paging activity monitoring reveals how heavily the system uses virtual memory. Tools like Windows Performance Monitor, Linux’s vmstat, or macOS Activity Monitor show page faults, page-ins, and page-outs. High paging rates, particularly page-outs (writing to swap), indicate memory pressure and performance problems. Occasional page-ins might be normal as programs access data they haven’t used recently, but constant paging means insufficient physical memory for the workload.

Response time degradation from paging can be dramatic. Opening a program that’s been idle and has paged out might take seconds rather than milliseconds as the system retrieves all its pages from disk. Switching between applications might cause delays as each application’s working set pages back in. These delays are distinctive—hard drive activity lights flash, and the system feels momentarily frozen as it waits for disk operations.

Memory leak impact becomes more severe with virtual memory because leaky programs can consume not just physical memory but also swap space. A program that leaks memory gradually consumes more virtual memory, eventually causing system-wide memory pressure. With virtual memory, the leak can grow larger before causing obvious problems, but when problems do occur, they affect the entire system through paging rather than just the leaky application.

The performance cliff when RAM fills describes how system performance remains good until physical memory is exhausted, then drops dramatically as paging begins. With sufficient RAM, virtual memory adds negligible overhead. As RAM fills, occasional paging causes minor slowdowns. Once RAM is completely full and the system constantly pages, performance collapses. This non-linear relationship means adding RAM often produces dramatic improvements in systems that were paging heavily.

Optimizing Systems with Virtual Memory Understanding

Understanding virtual memory helps optimize systems for better performance within memory constraints.

Adding physical RAM remains the most effective optimization for systems that page frequently. More RAM means less paging, directly improving performance. The performance improvement from adding RAM to a paging system is typically more dramatic than improvements from faster processors or storage because eliminating the million-fold speed difference between RAM and disk dwarfs other optimizations.

Closing unnecessary programs frees memory for active applications. Every running program consumes memory, and programs you’re not actively using still occupy RAM that could serve programs you are using. Regularly closing unused applications reduces memory pressure and paging.

Identifying memory-hungry applications helps target optimization efforts. Some applications consume disproportionate memory—web browsers with many tabs, video editors working with large files, virtual machines, or poorly optimized programs. Monitoring per-application memory use identifies culprits, allowing you to close them, reduce their memory consumption, or find more efficient alternatives.

Adjusting swap settings provides limited optimization potential. Increasing swap space doesn’t improve performance—it just allows more thrashing before the system becomes completely unresponsive. Decreasing swap can make the system fail faster when memory is exhausted rather than limping along slowly. The main swap optimization is ensuring it’s on the fastest available storage.

Using lighter-weight alternatives to memory-intensive applications can significantly reduce memory requirements. Browser editions optimized for low memory, email clients that don’t cache entire mailboxes, or document editors without extensive features all consume less memory while still providing needed functionality.

Virtual Memory Across Different Operating Systems

Different operating systems implement virtual memory with various specific characteristics worth understanding.

Windows uses a pagefile.sys file typically on the system drive, with configurable size and location. Windows tends to page relatively aggressively, moving infrequently accessed pages to disk even when physical memory isn’t completely full, which can improve performance by keeping more filesystem cache in memory. Windows Memory Compression, introduced in Windows 10, compresses pages in memory before paging them to disk, often avoiding disk I/O entirely while still freeing physical memory.

Linux virtual memory is highly configurable through the swappiness parameter, which controls how aggressively the system swaps. Low swappiness makes Linux prefer using filesystem cache over swap, keeping applications in memory longer. High swappiness more readily moves application pages to swap to make room for filesystem cache. The optimal setting depends on workload—servers with I/O-intensive operations might prefer higher swappiness, while desktops typically prefer lower values to keep interactive applications responsive.

macOS virtual memory management emphasizes application responsiveness. macOS aggressively compresses memory before paging and maintains detailed statistics about which pages belong to which applications. When memory pressure increases, macOS might terminate entire background applications rather than paging them, betting that restarting them later if needed is better than allowing constant paging that degrades overall system performance.

Mobile operating systems like Android and iOS handle memory pressure differently than desktop systems because they typically lack traditional swap space due to flash storage wear concerns. Instead, they aggressively terminate background applications when memory runs low, essentially using application termination as a substitute for paging. Applications must save state and be prepared to restart from saved state, creating a user experience where background apps seem to remain running but actually terminate and restart as needed.

The Future of Virtual Memory

Virtual memory technology continues evolving as hardware capabilities change and new memory technologies emerge.

Persistent memory technologies like Intel Optane blur the line between RAM and storage, offering performance between traditional RAM and SSDs with data persistence. These technologies enable rethinking virtual memory—what if swap space were nearly as fast as RAM? Persistent memory allows dramatically reducing paging penalties, making virtual memory more practical for memory-intensive workloads.

Larger virtual address spaces in 64-bit systems eliminate practical limits on virtual memory size. 32-bit systems could address only 4GB virtually, which increasingly constrained applications. 64-bit virtual addresses support address spaces measured in exabytes, effectively unlimited for foreseeable needs. This allows applications to use virtual memory freely without worrying about virtual address exhaustion.

Machine learning might optimize page replacement decisions by predicting future access patterns based on learned behavior. Rather than reactive algorithms that respond to current access patterns, predictive systems could proactively manage memory based on understanding typical application behavior and user patterns.

Non-volatile RAM eliminates the distinction between volatile and persistent memory, potentially making virtual memory concepts obsolete. If memory retains contents without power, why swap to disk? However, practical NVRAM implementations still show performance differences between different memory tiers, meaning some form of memory hierarchy and management likely persists even with persistent memory.

Understanding Your System’s Memory Use

Virtual memory works largely invisibly, but understanding some signs of its operation helps interpret system behavior and diagnose problems.

Heavy disk activity when physical operations aren’t being performed often indicates paging. If your hard drive light blinks constantly while you’re not saving files or loading programs, the system is probably paging. This suggests memory pressure and potential performance problems.

Slow application switching, where brief delays occur when clicking between windows, suggests those applications paged out while inactive and are now paging back in. These delays are characteristic of insufficient memory for your typical workload.

System warnings about low memory are explicit indicators that available memory is exhausted and performance problems are imminent or occurring. These warnings deserve attention—closing applications or adding RAM would improve the situation.

Performance improvement from restarts occurs partly because restarting clears accumulated memory allocations, fragmentation, and inefficiencies. A system running poorly due to memory pressure often runs dramatically better after restart, which temporarily solves the problem though the underlying issue—insufficient memory for typical usage—remains.

Virtual memory represents one of operating system design’s most successful abstractions, enabling capabilities that would be impractical or impossible with physical memory alone. Understanding how it works, its benefits and costs, and how to optimize systems for effective virtual memory use makes you a more informed and capable computer user. The next time your system seems slow and the hard drive is busy despite you not actively using disk, you’ll understand that virtual memory is working hard to provide the illusion of abundant RAM, and you’ll know whether adding physical memory might dramatically improve performance.