Why Your First Project Matters More Than You Think

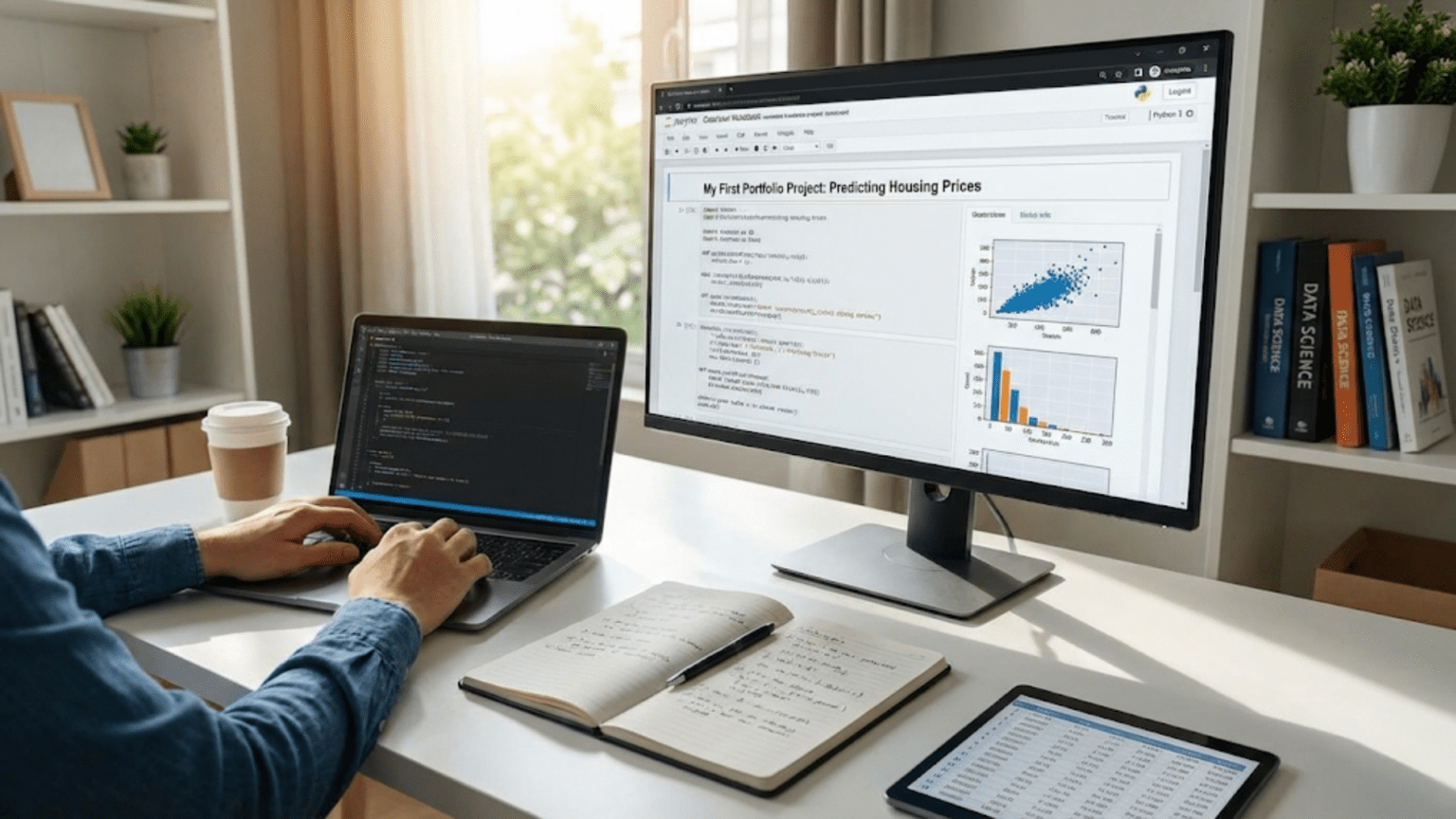

You have been learning data science for weeks or perhaps months, working through tutorials, completing exercises, and absorbing concepts about Python, statistics, and machine learning. The knowledge is accumulating in your head, and the exercises you have completed all worked correctly. Yet when you sit down to start your first real project from scratch, staring at a blank Jupyter notebook with no step-by-step instructions to follow, you might feel paralyzed. Where do you even begin? What question should you try to answer? How do you know if you are doing it right?

This moment of uncertainty when transitioning from guided tutorials to independent work is completely normal and represents a crucial turning point in your learning journey. Tutorials teach you individual skills in isolation with clear instructions and expected outcomes. Real projects require you to integrate multiple skills, make decisions without guidance, and navigate the messy reality of unclear requirements and imperfect data. This is uncomfortable precisely because it is where genuine learning happens. The struggle to figure things out for yourself is not a sign that you are not ready but rather evidence that you are pushing beyond passive consumption into active creation.

Your first portfolio project serves multiple critical purposes beyond just practicing skills. It forces you to experience the complete data science workflow from beginning to end, revealing gaps in your knowledge that tutorials never exposed. It creates concrete evidence of your capabilities that you can show to potential employers or clients, transforming abstract claims about what you know into tangible demonstrations of what you can do. It builds confidence through the accomplishment of creating something real from nothing, proving to yourself that you can actually apply what you have learned rather than just following instructions.

Most importantly, your first project establishes patterns and habits that will carry through all your future work. The choices you make about how to structure code, document your thinking, and present findings become templates that you will refine and reuse. Starting with good practices from your very first project, even though it will be imperfect, sets you up for continuous improvement rather than having to unlearn bad habits later. This is why taking the time to do your first project thoughtfully matters so much despite the urge to rush through it just to have something done.

This comprehensive guide walks you through building your first data science portfolio project from the initial idea through final presentation. I will help you choose an appropriate topic that is achievable but meaningful, guide you through each phase of execution from data collection through analysis to conclusions, show you how to document your work professionally, and teach you to present your project in ways that demonstrate your growing competence. By the end, you will not just have completed one project but will understand the process well enough to tackle your second, third, and fourth projects with increasing confidence.

Choosing Your First Project Topic: Achievable Yet Meaningful

The topic you choose for your first project significantly affects whether you will actually finish it and how much you will learn in the process. The ideal first project balances being simple enough to complete with your current skills while being complex enough to demonstrate meaningful capabilities and teach you something valuable.

Start by choosing a domain or topic that genuinely interests you rather than selecting something you think will impress employers. Your first project will require many hours of work, much of it frustrating as you debug errors and figure out unfamiliar techniques. Genuine interest in the subject matter provides motivation to push through these difficulties. If you find the topic boring, you will struggle to maintain energy through the inevitable challenges. Love of sports, curiosity about climate patterns, fascination with social media trends, or interest in health and fitness all provide equally valid starting points. The specific domain matters far less than your authentic engagement with it.

Ensure that data exists and is accessible for your chosen topic. The best project ideas mean nothing if you cannot actually obtain the data you need. Before committing to a topic, spend time searching for available datasets. Public data repositories like Kaggle, government data portals, and academic databases provide thousands of datasets across diverse domains. If you are interested in a topic but cannot find ready-made datasets, consider whether you can collect data yourself through web scraping or APIs, though this adds complexity that might be too much for a very first project.

Frame your project around a specific question rather than vague exploration. Weak framing sounds like “analyze movie data” or “look at weather patterns.” Strong framing asks specific questions: “What factors most strongly predict whether a movie will be profitable?” or “How has average temperature changed over the past fifty years in major cities?” Specific questions guide your analysis by giving you clear targets to work toward. You know when you have answered your question, whereas vague exploration can continue indefinitely without clear endpoints.

Choose questions that can be answered with the skills you currently have, erring on the side of too simple rather than too ambitious. Your first project is not the place to learn complex neural networks or advanced statistical modeling. Simple analyses using descriptive statistics, basic visualizations, and perhaps linear regression or logistic classification are entirely appropriate. You will have opportunities for more sophisticated techniques in later projects. For now, focus on executing a complete project well rather than demonstrating advanced methods poorly.

Avoid projects requiring extensive domain expertise you do not possess. Analyzing medical data to predict diseases requires medical knowledge to interpret results sensibly. Financial modeling requires understanding of markets and instruments. While domain knowledge can be learned, trying to acquire both domain expertise and data science skills simultaneously in your first project spreads your effort too thin. Choose domains where you either already have some knowledge or where the analysis does not require deep expertise to be meaningful.

Consider project scope carefully to ensure you can complete it in a reasonable timeframe. Your first project should take somewhere between twenty to forty hours of total work spread over two to four weeks. Much shorter and you are likely doing something too trivial to demonstrate meaningful skills. Much longer and you risk losing momentum or getting stuck on one project for months. Breaking a large interesting question into a smaller initial phase that you can complete quickly allows you to succeed while leaving room for future expansion.

Examples of good first project topics include analyzing Airbnb listing prices to identify what features command premium prices in a specific city, examining historical bike-sharing data to understand usage patterns and predict demand, studying movie ratings data to predict which films audiences will rate highly, analyzing employee attrition data to identify factors associated with employees leaving, or investigating historical weather data to examine temperature trends over time. All of these allow complete analyses with clear questions, available data, and techniques within reach of beginners.

Phase One: Getting and Understanding Your Data

Once you have chosen your topic and identified your data source, the first phase of your project involves actually obtaining the data and understanding what you are working with. This preparatory phase seems less exciting than analysis but is absolutely essential for success.

Download or access your chosen dataset and save it in a dedicated project folder with a clear structure. Create a folder for your project with subfolders for data, code, and output. Keep your raw data file separate and untouched, always working with copies so you can return to the original if needed. This basic organization prevents confusion as your project develops and makes it easier for others to understand your work.

Load your data into a pandas DataFrame and immediately perform initial examination. Display the first few rows to see what the data looks like. Check the shape to know how many observations and variables you have. Display column names and data types. Get summary statistics for numerical columns. This initial exploration tells you what you are working with before you try to do anything with it.

Create a data dictionary documenting what each variable means, what values it can take, and what units it uses if applicable. Many datasets come with documentation, but even when they do, creating your own concise reference helps you remember variable meanings as you work. If documentation is missing or unclear, you may need to infer meanings from the data itself, noting any uncertainties in your documentation.

Examine data quality systematically before attempting any analysis. Check for missing values in each column and note which variables have substantial missingness. Look for obviously impossible or unusual values that might indicate errors. Check whether categorical variables have the expected categories or whether there are typos or variations you need to standardize. Identify outliers in numerical variables and investigate whether they are errors or legitimate extreme values.

Understanding your data includes understanding where it came from and what it represents. Who collected this data and why? What time period does it cover? What population does it represent? Are there any selection biases in how data was collected that might affect your analysis? These contextual questions help you interpret results correctly and identify limitations of your analysis. If you are using a public dataset, research its origin and read any available documentation about data collection methods.

Create initial visualizations to understand distributions and relationships. Histograms show you the distributions of numerical variables. Bar charts show frequency of categorical variables. Scatter plots reveal relationships between numerical variables. These exploratory visualizations are for your understanding, not for presentation, so do not worry about making them pretty yet. The goal is learning what patterns exist in your data.

Document your initial observations and questions that arise during exploration. What patterns do you notice? What surprises you? What variables seem to relate to each other? What concerns do you have about data quality? Writing down these observations helps organize your thinking and guides subsequent analysis steps. These notes might later become part of your project narrative explaining your analytical journey.

This phase typically takes several hours as you familiarize yourself with your data thoroughly. Resist the urge to rush through exploration to get to “real analysis.” Understanding your data deeply before analyzing it prevents wasted effort pursuing analyses that cannot work with your data or misinterpreting results because you did not understand what variables actually measured.

Phase Two: Cleaning and Preparing Your Data

With understanding of what you are working with, the second phase involves transforming your raw data into a clean dataset ready for analysis. Real data is always messy, and learning to handle that messiness is a core data science skill that your first project must develop.

Handle missing values using strategies appropriate to your data and analysis goals. For variables missing only a few values, you might drop those rows if losing them will not significantly reduce your sample size. For variables missing many values, consider whether the variable is important enough to keep despite missingness. If so, you might impute missing values using the mean or median for numerical variables or the mode for categorical variables. Document whatever approach you choose and explain why you chose it.

Address data type issues by converting variables to appropriate types. Dates stored as strings need conversion to datetime types. Categorical variables stored as numbers might need conversion to categorical types. Numbers stored as strings because of formatting characters need cleaning and conversion to numerical types. Proper data types ensure that operations behave correctly and prevent errors in analysis.

Standardize categorical variables to ensure consistency. If a city name appears as both “New York” and “new york,” these need standardization to a single form. If product categories have slight variations or typos, clean them to consistent labels. This standardization prevents treating equivalent values as different categories just because of formatting differences.

Create derived variables that will be useful for your analysis. Calculating someone’s age from their birth date, combining first and last names into full names, or computing ratios between related variables often makes analysis clearer. If you will analyze temporal patterns, extracting components like month, day of week, or hour from timestamps creates variables you can group by.

Handle outliers thoughtfully rather than automatically removing all extreme values. Investigate whether outliers are errors that should be corrected or legitimate extreme values that should be kept. Some analyses require removing outliers to prevent them from dominating results, while other analyses specifically focus on understanding extreme cases. Make conscious decisions based on your analytical goals rather than mechanically following rules.

Filter your data to the subset relevant for your analysis if you do not need all observations. If you are analyzing bike usage in summer months, filter to just those months. If you are studying a specific city, filter to observations from that location. Reducing data to what you actually need for your question simplifies subsequent analysis and makes your work more focused.

Document every cleaning and preparation step in your code with comments explaining what you are doing and why. Your future self will thank you when you need to understand or modify this code weeks later. Others reviewing your work need to see what transformations you applied to understand your analysis. Clear documentation of data preparation is a mark of professional work.

Validate that your cleaning worked correctly by checking the results of each transformation. After handling missing values, verify that missingness patterns match your expectations. After standardizing categories, check that all variations are gone. After filtering, confirm that you retained the right observations. This validation catches errors early before they corrupt subsequent analysis.

Save your cleaned data as a separate file that you will use for all subsequent analysis. This allows you to reload cleaned data without rerunning all cleaning steps each time you work on the project. It also clearly separates raw data from processed data, making your workflow more organized and reproducible.

Data cleaning and preparation often takes more time than analysis itself, sometimes fifty to seventy percent of total project time. This is normal and expected. Professional data scientists spend the majority of their time on these tasks because analysis built on messy data produces unreliable results. Taking the time to clean data properly is not wasted effort but rather essential groundwork that enables everything else.

Phase Three: Exploratory Data Analysis and Visualization

With clean data prepared, the third phase involves systematic exploration to understand patterns, relationships, and characteristics that will inform your analysis and help answer your project question.

Start with univariate analysis examining each variable individually. Create histograms for numerical variables to see their distributions. Are they roughly normal, skewed, or bimodal? Create bar charts for categorical variables to see frequency of different categories. Are categories balanced or highly imbalanced? Calculate summary statistics including means, medians, standard deviations, and percentiles. These give you quantitative understanding of each variable’s characteristics.

Progress to bivariate analysis examining relationships between pairs of variables. Create scatter plots for pairs of numerical variables to see whether relationships exist. Calculate correlation coefficients to quantify linear relationships. Use grouped box plots to compare distributions of numerical variables across categories. Create cross-tabulations to examine how categorical variables relate to each other. These bivariate explorations reveal which variables associate with each other and which might be useful for predicting your outcome of interest.

Look for patterns related specifically to your project question. If you are predicting movie profitability, examine how budget, genre, release timing, and other factors relate to revenue. If you are studying temperature trends, look at changes over time and differences across locations. Your question guides which relationships matter most and deserve closer examination.

Create visualizations that effectively communicate patterns you discover. While exploratory visualizations for your own understanding can be quick and rough, visualizations you will include in your final presentation need more care. Add clear titles, axis labels, and legends. Choose colors thoughtfully. Make sure plots are readable and convey patterns clearly. Good visualization is a skill that improves with practice, and your first project is where you begin developing it.

Document interesting findings and surprising observations as you explore. If you expected two variables to correlate but they do not, note that. If you find unexpected patterns, document them. If certain groups behave very differently than others, record those differences. These observations might become part of your final narrative or might guide deeper analysis to understand what is happening.

Consider multiple perspectives on your data by cutting it in different ways. Look at overall patterns, then examine subgroups separately to see if patterns hold across all groups or differ by category. Examine trends over time if temporal data exists. Compare different locations, categories, or segments. Comprehensive exploration looks at data from multiple angles rather than accepting the first pattern you notice.

Do not skip this exploration phase to jump straight to modeling. Even though running machine learning algorithms might seem like the exciting part of data science, exploratory analysis teaches you far more about your data and often reveals insights directly without needing complex models. Many of the most valuable findings in real data science work come from thorough exploration rather than sophisticated modeling. Build the habit of comprehensive exploration in your first project so it becomes natural in all future work.

Use this exploration to refine your project question if needed. Sometimes initial exploration reveals that your original question cannot be answered with available data, or it suggests more interesting questions you had not considered. Adjusting your question based on what you learn from exploring is completely appropriate and shows intellectual flexibility rather than weakness.

Phase Four: Analysis and Modeling

With comprehensive understanding of your data from exploration, the fourth phase applies analytical techniques or builds models to answer your project question. The specific techniques you use depend on your question, but the approach to applying them systematically applies across techniques.

Choose analysis methods appropriate to your question and data type. If predicting a categorical outcome, use classification methods. If predicting a numerical outcome, use regression. If finding patterns without a specific outcome variable, use clustering or other unsupervised methods. If testing whether groups differ, use hypothesis tests. Match your methods to your goals rather than using techniques just because you know them.

Start with simple methods before trying complex ones. Run basic linear regression before neural networks. Try logistic regression before random forests. Simple methods provide baselines that more complex methods must beat to justify their added complexity. They also help you understand fundamental relationships that complex methods might obscure. Many real projects find that simple methods work perfectly well, making complexity unnecessary.

Split your data into training and test sets if you are building predictive models. Train your model on the training set and evaluate it on the held-out test set to get honest estimates of performance on new data. This separation between training and testing is fundamental to avoiding overfitting and producing models that actually generalize. Use an eighty-twenty or seventy-thirty split depending on your data size.

Train your chosen models or conduct your chosen analyses following best practices. For models, this means properly preprocessing features, tuning hyperparameters if appropriate, and validating results. For hypothesis tests, this means checking assumptions and interpreting results correctly. Apply techniques properly rather than just running functions without understanding what they do.

Evaluate results using appropriate metrics for your problem. Classification models use accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores. Regression models use mean squared error or R-squared. Hypothesis tests use p-values. Choose metrics that actually measure what you care about and report them honestly, including both strengths and weaknesses of your results.

Interpret your results in the context of your original question. What do the results tell you about your question? Can you answer it confidently based on your analysis? What caveats or limitations should you acknowledge? Good analysis includes honest assessment of what you can and cannot conclude from your work.

Try multiple approaches if time permits and compare their results. Run several different algorithms and see which performs best. Try different feature sets or preprocessing approaches. This exploration teaches you about how different methods behave and might reveal that your results are robust across approaches or that they depend heavily on specific choices.

Document your analytical decisions and reasoning. Why did you choose this method? What alternatives did you consider? What hyperparameters did you select and why? This documentation helps others understand your work and helps you remember your thinking when you revisit the project later.

Be prepared for results that do not match your expectations or hopes. Maybe your model performs poorly, or your hypothesis test is not significant, or patterns are weaker than you anticipated. These are still legitimate results that teach you something. Honestly reporting null or weak results demonstrates scientific integrity and is far more valuable than forcing positive results where they do not exist.

Phase Five: Creating Your Project Narrative and Documentation

The final phase transforms your analytical work into a coherent story that others can understand and appreciate. This narrative and documentation phase is where your project becomes truly presentable as portfolio material.

Write a clear introduction explaining what question you are investigating and why it matters. Set up context for readers unfamiliar with your topic. Explain what motivated this question and what you hope to learn. This introduction frames everything that follows and helps readers understand your goals.

Describe your data including where it came from, what time period it covers, how many observations it contains, and what variables you are working with. Explain any data collection methods that affect interpretation. Acknowledge data limitations or biases you identified. This transparency about data quality demonstrates mature understanding that real data is never perfect.

Walk readers through your data preparation and cleaning steps at a high level. You do not need to show every line of code, but you should explain major transformations like how you handled missing values, what outliers you addressed, and what derived variables you created. This documentation enables others to understand and potentially reproduce your work.

Present key findings from your exploratory analysis using well-designed visualizations and clear explanations. Show patterns you discovered and relationships you found interesting. Explain what these patterns suggest about your question. This section builds up evidence and understanding before you present final results.

Present your analysis results clearly with appropriate visualizations and metrics. If you built predictive models, show performance metrics and perhaps visualizations of predictions versus actual values. If you conducted hypothesis tests, report test statistics and p-values with interpretation. If you found clusters, visualize the clusters and explain what characterizes each group.

Discuss limitations and caveats honestly. What assumptions did you make? What does your analysis not cover? What alternative explanations might exist for your findings? Acknowledging limitations shows intellectual honesty and mature understanding rather than weakness. All analysis has limitations, and discussing them openly builds credibility.

Conclude with clear answers to your original question based on your analysis. What did you learn? What are the key takeaways? What might be interesting directions for future investigation? A strong conclusion ties everything together and leaves readers with clear understanding of what you found.

Include well-commented code that others can read and understand. Every significant code block should have comments explaining what it does and why. Variable names should be meaningful rather than cryptic. Code should be organized logically rather than scattered randomly. While your code does not need to be perfect, it should be readable and demonstrate professional practices.

Create a README file for your project repository explaining what the project is, what files are included, what dependencies are needed to run the code, and how to navigate the project. This README helps others engage with your work and shows you understand how to document projects professionally.

Consider writing a blog post version of your project that presents the narrative in a more accessible format than a technical notebook. Blog posts can reach broader audiences and demonstrate your communication skills. They do not need to include all code details but should tell the story of your analysis clearly.

Common First Project Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Learning from common mistakes helps you avoid pitfalls that trip up many beginners, saving you time and frustration.

Choosing an overly ambitious project for your first attempt leads to getting stuck or never finishing. Resist the temptation to tackle complex questions or use advanced techniques you barely understand. Simple completed projects beat sophisticated unfinished ones. Save ambitious projects for when you have more experience.

Spending too much time on perfect data cleaning or preprocessing prevents ever getting to analysis. While data cleaning matters, perfectionism here is counterproductive. Clean data well enough to support reliable analysis, but do not spend weeks pursuing perfect data quality that is neither achievable nor necessary.

Jumping straight to modeling without adequate exploration means you do not understand your data when interpreting results. Always explore thoroughly before modeling. The exploration phase teaches you what to expect from modeling and helps you recognize when results seem wrong.

Ignoring obvious data problems or anomalies because you do not know how to fix them leads to unreliable results. If you notice issues, address them even if addressing them is difficult. Document problems you cannot fully resolve so readers know about limitations.

Presenting only the code without explanation makes your project incomprehensible to others. Always explain what you are doing and why in prose, not just in code comments. Your project should tell a story that non-technical readers can follow even if they cannot read code.

Using overly complex visualizations or too many plots clutters your presentation without adding value. Choose a smaller number of clear, effective visualizations over many mediocre ones. Each visualization should serve a specific purpose in your narrative.

Failing to validate results means you might be presenting errors or misleading findings. Always sanity-check that results make sense. If patterns seem too perfect, investigate whether something went wrong. If results contradict expectations, understand why before reporting them.

Not iterating on your work means your first draft becomes your final product despite flaws you noticed. Review your project multiple times, each time improving some aspect. Polish comes from iteration, not from getting everything perfect on the first attempt.

Conclusion

Your first data science portfolio project represents a crucial milestone in your learning journey that transforms theoretical knowledge into practical capability. By choosing an achievable topic that genuinely interests you, working systematically through data collection, cleaning, exploration, analysis, and documentation, and presenting your work professionally, you create concrete evidence of your abilities while developing habits and skills that will serve you throughout your career.

The project process teaches you far more than any tutorial can by forcing you to integrate multiple skills, make decisions without guidance, and navigate the messy reality of real-world data analysis. The struggle of figuring things out independently is uncomfortable but essential for genuine learning. Your first project will be imperfect, but completing it demonstrates that you can apply data science skills independently rather than just following instructions.

Start simple with clear questions and accessible data, focusing on executing the complete workflow well rather than demonstrating advanced techniques. Document your work thoroughly, explain your thinking clearly, and acknowledge limitations honestly. These professional practices matter more than technical sophistication and distinguish quality work from superficial analysis.

Remember that your first project is exactly that—the first of many. It does not need to be perfect or revolutionary. It needs to demonstrate that you can take a question from initial idea through data analysis to documented conclusions. Each subsequent project will teach you more and improve your skills, but you must complete the first one to begin that journey. Choose your topic, download your data, and start working. The best time to begin building your portfolio is right now.

Key Takeaways

Your first data science portfolio project serves multiple crucial purposes beyond practicing skills including forcing you to experience the complete workflow revealing knowledge gaps, creating concrete evidence of capabilities demonstrating what you can do rather than just claiming knowledge, building confidence through accomplishment proving you can apply learning independently, and establishing patterns and habits for all future work making good practices automatic rather than afterthoughts.

Choose project topics that balance being simple enough to complete with current skills while being complex enough to demonstrate meaningful capabilities by selecting domains that genuinely interest you providing motivation through inevitable challenges, ensuring data exists and is accessible before committing to topics, framing around specific answerable questions rather than vague exploration, and choosing questions addressable with current skills erring toward too simple rather than too ambitious.

The complete project workflow progresses systematically through getting and understanding your data by loading it into pandas and performing initial examination, cleaning and preparing data by handling missing values and standardizing formats with documentation of all steps, exploratory data analysis examining distributions and relationships from multiple perspectives, analysis and modeling applying appropriate techniques to answer your question, and creating coherent narratives with professional documentation transforming analytical work into presentable portfolio material.

Data cleaning and preparation typically consume fifty to seventy percent of total project time and must not be rushed because analysis built on messy data produces unreliable results, requiring systematic approaches to missing values using appropriate strategies, standardization of categorical variables ensuring consistency, creation of derived variables useful for analysis, thoughtful handling of outliers based on investigation rather than automatic removal, and validation that transformations worked correctly.

Professional documentation and presentation separate quality portfolio projects from amateur work through clear introductions explaining questions and their importance, comprehensive descriptions of data sources and limitations, explanations of preparation steps at appropriate detail levels, well-designed visualizations with proper labels and titles, honest discussion of limitations and caveats, clear conclusions answering original questions, well-commented readable code, and README files helping others navigate and understand projects.

Common first project mistakes to avoid include choosing overly ambitious topics for initial attempts, perfectionism in data cleaning preventing progress to analysis, skipping adequate exploration to jump straight to modeling, ignoring data problems because solutions are unclear, presenting only code without prose explanation, using too many complex visualizations cluttering presentations, failing to validate results for sanity and correctness, and not iterating to improve work beyond first drafts.