When your program needs to choose between multiple options based on a single value, you have two primary tools at your disposal: if-else chains and switch statements. While if-else statements can handle virtually any decision-making scenario, switch statements provide a cleaner, more readable alternative for a specific but common situation—when you’re comparing a single variable against multiple constant values. Understanding when and how to use switch statements makes your code more maintainable and expresses your intent more clearly to other programmers reading your code.

The switch statement evaluates an expression once and compares its result against a series of constant values called cases. When a match is found, the code associated with that case executes. This differs from an if-else chain, which potentially evaluates multiple conditions separately. For certain types of problems, particularly menu systems and state machines, switch statements produce code that’s easier to read and understand than equivalent if-else chains.

Let me start with a simple example that demonstrates the basic syntax and structure of a switch statement:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int day = 3;

switch (day) {

case 1:

std::cout << "Monday" << std::endl;

break;

case 2:

std::cout << "Tuesday" << std::endl;

break;

case 3:

std::cout << "Wednesday" << std::endl;

break;

case 4:

std::cout << "Thursday" << std::endl;

break;

case 5:

std::cout << "Friday" << std::endl;

break;

case 6:

std::cout << "Saturday" << std::endl;

break;

case 7:

std::cout << "Sunday" << std::endl;

break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid day" << std::endl;

break;

}

return 0;

}Let me walk you through each component of this switch statement. The switch keyword begins the statement, followed by parentheses containing the expression to evaluate—in this case, the variable day. The curly braces contain all the cases. Each case keyword is followed by a constant value and a colon. The code after the colon executes when the switch expression matches that case value. The break statement at the end of each case causes execution to exit the switch statement entirely. The default case handles values that don’t match any specific case, similar to a final else clause in an if-else chain.

When this program runs with day set to three, it evaluates the switch expression and compares three against each case value in order. When it reaches case three, it finds a match, executes the associated code (printing “Wednesday”), then encounters the break statement and exits the switch. The subsequent cases never execute because the break caused an early exit.

The break statement’s role in switch statements deserves special emphasis because its behavior differs from loops. In loops, break exits the loop. In switch statements, break exits the switch. Without break, something surprising happens—execution continues into the next case, a behavior called fall-through:

int value = 2;

switch (value) {

case 1:

std::cout << "One" << std::endl;

// No break - falls through!

case 2:

std::cout << "Two" << std::endl;

// No break - falls through!

case 3:

std::cout << "Three" << std::endl;

break;

default:

std::cout << "Other" << std::endl;

}When value is two, this code prints both “Two” and “Three” because the case 2 block has no break statement. Execution falls through to case 3, which also executes before encountering a break. This fall-through behavior is sometimes useful but more often represents a bug—forgetting to include break is one of the most common mistakes with switch statements.

However, fall-through can be intentionally useful when multiple cases should execute the same code:

char grade;

std::cout << "Enter your grade (A-F): ";

std::cin >> grade;

switch (grade) {

case 'A':

case 'a':

std::cout << "Excellent!" << std::endl;

break;

case 'B':

case 'b':

std::cout << "Good job!" << std::endl;

break;

case 'C':

case 'c':

std::cout << "Satisfactory" << std::endl;

break;

case 'D':

case 'd':

std::cout << "Needs improvement" << std::endl;

break;

case 'F':

case 'f':

std::cout << "Failing" << std::endl;

break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid grade" << std::endl;

break;

}This pattern handles both uppercase and lowercase input by placing consecutive cases without code between them. When grade is ‘A’, case ‘A’ matches but contains no code, so execution falls through to case ‘a’, which contains the actual code. This technique eliminates code duplication when multiple values should produce the same result.

The default case handles all values not explicitly covered by other cases. While optional, including a default case is good practice because it makes your intentions explicit—you’ve considered what should happen for unexpected values:

int month = 13;

switch (month) {

case 1: std::cout << "January"; break;

case 2: std::cout << "February"; break;

case 3: std::cout << "March"; break;

// ... other months ...

case 12: std::cout << "December"; break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid month: " << month;

break;

}Without the default case, invalid values like thirteen would cause the switch to do nothing, which might hide bugs. The default case makes the error visible.

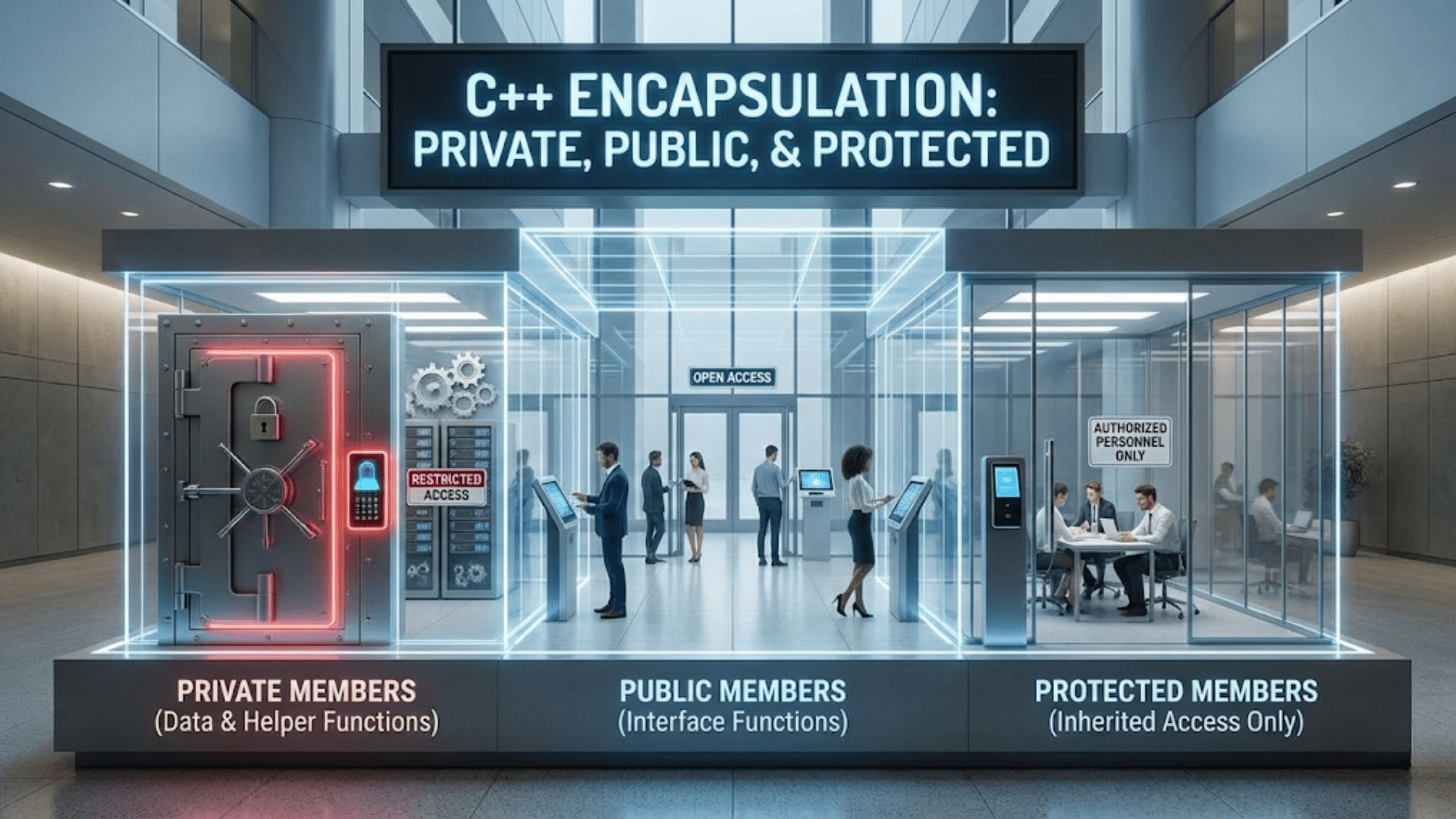

Switch statements have important limitations that restrict when you can use them. The switch expression and all case values must be integral types—integers, characters, or enumerations. You cannot switch on floating-point numbers, strings, or boolean values:

// VALID - switching on integer

int choice = 2;

switch (choice) { /* ... */ }

// VALID - switching on character

char letter = 'A';

switch (letter) { /* ... */ }

// INVALID - can't switch on floating-point

double value = 3.14;

switch (value) { /* ... */ } // Compilation error!

// INVALID - can't switch on string

std::string color = "red";

switch (color) { /* ... */ } // Compilation error!Case values must be compile-time constants—literal values or constant expressions that the compiler can evaluate. You cannot use variables as case values:

const int OPTION_A = 1;

int optionB = 2;

int choice = 1;

switch (choice) {

case OPTION_A: // Valid - constant

break;

case optionB: // Invalid - variable

break;

}These limitations mean that switch statements aren’t appropriate for every decision-making scenario. When you need to compare strings, test ranges of values, or use complex conditions, if-else chains remain necessary.

Let me demonstrate when switch statements provide advantages over if-else. Consider a simple calculator program:

// Using if-else chain

char operation;

double num1, num2, result;

std::cout << "Enter operation (+, -, *, /): ";

std::cin >> operation;

std::cout << "Enter two numbers: ";

std::cin >> num1 >> num2;

if (operation == '+') {

result = num1 + num2;

} else if (operation == '-') {

result = num1 - num2;

} else if (operation == '*') {

result = num1 * num2;

} else if (operation == '/') {

if (num2 != 0) {

result = num1 / num2;

} else {

std::cout << "Error: Division by zero" << std::endl;

return 1;

}

} else {

std::cout << "Invalid operation" << std::endl;

return 1;

}

std::cout << "Result: " << result << std::endl;Now compare this to the switch version:

char operation;

double num1, num2, result;

std::cout << "Enter operation (+, -, *, /): ";

std::cin >> operation;

std::cout << "Enter two numbers: ";

std::cin >> num1 >> num2;

switch (operation) {

case '+':

result = num1 + num2;

break;

case '-':

result = num1 - num2;

break;

case '*':

result = num1 * num2;

break;

case '/':

if (num2 != 0) {

result = num1 / num2;

} else {

std::cout << "Error: Division by zero" << std::endl;

return 1;

}

break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid operation" << std::endl;

return 1;

}

std::cout << "Result: " << result << std::endl;The switch version is cleaner because the intent is immediately clear—we’re choosing between different operations based on a single value. The if-else version requires reading each condition to understand the pattern. For this type of multi-way branch based on equality comparisons against a single variable, switch statements communicate intent more effectively.

Menu-driven programs particularly benefit from switch statements:

#include <iostream>

void displayMenu() {

std::cout << "\n=== Main Menu ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "1. New Game" << std::endl;

std::cout << "2. Load Game" << std::endl;

std::cout << "3. Settings" << std::endl;

std::cout << "4. Exit" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Choice: ";

}

int main() {

int choice;

bool running = true;

while (running) {

displayMenu();

std::cin >> choice;

switch (choice) {

case 1:

std::cout << "Starting new game..." << std::endl;

// Game logic here

break;

case 2:

std::cout << "Loading game..." << std::endl;

// Load logic here

break;

case 3:

std::cout << "Opening settings..." << std::endl;

// Settings logic here

break;

case 4:

std::cout << "Goodbye!" << std::endl;

running = false;

break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid choice. Please try again." << std::endl;

break;

}

}

return 0;

}This pattern—displaying a menu, reading a choice, and executing different code based on that choice—appears constantly in interactive programs. The switch statement makes the correspondence between menu items and their actions visually clear.

You can declare variables within switch statements, but scope rules require careful attention. Variables declared in one case are visible in other cases, which can cause problems:

switch (choice) {

case 1:

int value = 10; // Visible in other cases!

std::cout << value << std::endl;

break;

case 2:

value = 20; // Uses the same variable from case 1

std::cout << value << std::endl;

break;

}This code is problematic because the variable declaration in case 1 is visible in case 2, but case 2 might execute without case 1 ever executing, leaving value uninitialized. The solution is to create a new scope using curly braces:

switch (choice) {

case 1: {

int value = 10;

std::cout << value << std::endl;

break;

}

case 2: {

int value = 20; // Different variable, local to this case

std::cout << value << std::endl;

break;

}

}The curly braces create separate scopes for each case, preventing the variables from interfering with each other.

Nesting switch statements handles more complex decision trees:

char category;

int subchoice;

std::cout << "Category (A/B): ";

std::cin >> category;

switch (category) {

case 'A':

std::cout << "A subchoices: 1) Option 1 2) Option 2" << std::endl;

std::cin >> subchoice;

switch (subchoice) {

case 1:

std::cout << "A - Option 1" << std::endl;

break;

case 2:

std::cout << "A - Option 2" << std::endl;

break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid A subchoice" << std::endl;

}

break;

case 'B':

std::cout << "B subchoices: 1) Option 1 2) Option 2" << std::endl;

std::cin >> subchoice;

switch (subchoice) {

case 1:

std::cout << "B - Option 1" << std::endl;

break;

case 2:

std::cout << "B - Option 2" << std::endl;

break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid B subchoice" << std::endl;

}

break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid category" << std::endl;

}While nested switches work, too much nesting makes code hard to follow. Consider breaking complex switches into separate functions instead.

Enumerations work particularly well with switch statements because the compiler can verify that you’ve handled all possible values:

enum Color {

RED,

GREEN,

BLUE,

YELLOW

};

void describeColor(Color color) {

switch (color) {

case RED:

std::cout << "Red like fire" << std::endl;

break;

case GREEN:

std::cout << "Green like grass" << std::endl;

break;

case BLUE:

std::cout << "Blue like sky" << std::endl;

break;

case YELLOW:

std::cout << "Yellow like sun" << std::endl;

break;

// Some compilers warn if you forget a case

}

}Many compilers can warn if your switch doesn’t handle all enumeration values, helping catch bugs when you add new values to an enumeration but forget to update switch statements.

Return statements in switch cases provide an alternative to break:

int getDaysInMonth(int month) {

switch (month) {

case 1: case 3: case 5: case 7: case 8: case 10: case 12:

return 31;

case 4: case 6: case 9: case 11:

return 30;

case 2:

return 28; // Simplified - ignoring leap years

default:

return -1; // Error value

}

}Using return instead of break is cleaner when the function’s purpose is to return different values based on the switch expression. You don’t need break when return exits the function entirely.

Performance considerations sometimes favor switch statements over if-else chains. Compilers can optimize switch statements into jump tables—arrays of addresses that allow direct jumping to the correct case without comparing values sequentially. This makes switches with many cases potentially faster than equivalent if-else chains. However, for small numbers of cases (fewer than five or so), the performance difference is negligible, and readability should guide your choice.

Let me show you a comprehensive example that demonstrates best practices—a text-based adventure game using switch statements effectively:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

enum class GameState {

MENU,

PLAYING,

INVENTORY,

QUIT

};

enum class Direction {

NORTH,

SOUTH,

EAST,

WEST

};

void displayMainMenu() {

std::cout << "\n=== Adventure Game ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "1. Start Game" << std::endl;

std::cout << "2. Instructions" << std::endl;

std::cout << "3. Quit" << std::endl;

}

void displayGameOptions() {

std::cout << "\nWhat do you do?" << std::endl;

std::cout << "1. Go North" << std::endl;

std::cout << "2. Go South" << std::endl;

std::cout << "3. Go East" << std::endl;

std::cout << "4. Go West" << std::endl;

std::cout << "5. Check Inventory" << std::endl;

std::cout << "6. Return to Menu" << std::endl;

}

int main() {

GameState state = GameState::MENU;

int choice;

while (state != GameState::QUIT) {

switch (state) {

case GameState::MENU: {

displayMainMenu();

std::cin >> choice;

switch (choice) {

case 1:

std::cout << "\nYou enter the dungeon..." << std::endl;

state = GameState::PLAYING;

break;

case 2:

std::cout << "\nUse numbers to make choices." << std::endl;

break;

case 3:

state = GameState::QUIT;

break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid choice" << std::endl;

}

break;

}

case GameState::PLAYING: {

displayGameOptions();

std::cin >> choice;

switch (choice) {

case 1:

std::cout << "You head north and find a treasure chest!" << std::endl;

break;

case 2:

std::cout << "You head south and encounter a monster!" << std::endl;

break;

case 3:

std::cout << "You head east and find a locked door." << std::endl;

break;

case 4:

std::cout << "You head west and see a mysterious glow." << std::endl;

break;

case 5:

state = GameState::INVENTORY;

break;

case 6:

state = GameState::MENU;

break;

default:

std::cout << "Invalid action" << std::endl;

}

break;

}

case GameState::INVENTORY: {

std::cout << "\n=== Inventory ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Your inventory is empty." << std::endl;

std::cout << "Press 1 to return: ";

std::cin >> choice;

state = GameState::PLAYING;

break;

}

case GameState::QUIT:

// Nothing to do - will exit loop

break;

}

}

std::cout << "Thanks for playing!" << std::endl;

return 0;

}This example demonstrates using enumerations with switches for state machines, nesting switches appropriately, handling all cases including default, and using scoped cases to avoid variable scope issues. The code structure makes the game’s flow easy to understand and modify.

Common mistakes with switch statements include forgetting break statements:

// Unintentional fall-through

switch (value) {

case 1:

doSomething();

// Oops! Forgot break - falls through to case 2

case 2:

doSomethingElse();

break;

}Using non-constant expressions in cases:

int maxValue = 100;

switch (value) {

case maxValue: // Error! maxValue is not a constant

break;

}And attempting to switch on unsupported types:

std::string name = "Alice";

switch (name) { // Error! Can't switch on strings

case "Alice":

break;

}Understanding these limitations helps you choose between switch and if-else appropriately.

Key Takeaways

Switch statements provide a clean, readable way to choose between multiple options based on a single integral value. They work by evaluating an expression once and comparing it against multiple case values, executing the code associated with the first match. The break statement is essential in most cases to prevent fall-through, though intentional fall-through can be useful for handling multiple values with the same code.

Switch statements require integral types (integers, characters, enumerations) and constant case values. They cannot handle floating-point numbers, strings, or range comparisons. When you need these capabilities, if-else statements remain necessary. However, for menu systems, state machines, and multi-way branches based on equality comparisons, switch statements produce clearer, more maintainable code than equivalent if-else chains.

Always include a default case to handle unexpected values explicitly. Use curly braces around case blocks when you need local variables. Consider using enumerations with switches because compilers can verify you’ve handled all possible values. While switch statements can offer performance benefits with many cases, choose them primarily for code clarity rather than performance until profiling identifies a bottleneck.