Humans experience the world through five traditional senses that provide rich, continuous streams of information about our surroundings. We see colors and shapes, hear sounds from all directions, feel textures and temperatures, smell chemical signatures in the air, and taste substances we consume. This multi-modal perception happens so effortlessly that we rarely think about the complex biological machinery that makes it possible. When we design robots, we face the fundamental challenge of giving machines similar perceptual capabilities using entirely different mechanisms. Understanding how robots sense their environment reveals both the remarkable solutions engineers have developed and the significant gaps that still exist between human and robotic perception.

Robot perception serves as the foundation for autonomous behavior. A robot operating in the real world must gather information about its surroundings to make meaningful decisions. Where are obstacles located? How far away is that wall? Is the floor level or sloped? What objects are present in the workspace? The answers to these questions come from sensors that convert physical phenomena into electrical signals the robot’s control system can process. The quality, variety, and integration of these sensors fundamentally determine what tasks a robot can accomplish and how well it can perform them.

This article explores the major categories of perception available to robots, examining how different sensor types work, what information they provide, and where they excel or struggle. You will discover that robot perception often differs dramatically from human sensing, sometimes providing capabilities we lack while missing aspects of perception we take for granted. Understanding these perceptual tools and their characteristics helps you choose appropriate sensors for your robots and design behaviors that work within the capabilities and limitations of robotic perception.

Vision: Seeing the World Through Cameras

Vision represents one of the most information-rich sensing modalities available to robots. A single camera frame contains millions of pixels, each encoding color and brightness information. This data density allows vision-based systems to recognize objects, read text, detect edges, estimate distances, and perform countless other perceptual tasks. The human visual system processes visual information so naturally that vision seems like the obvious choice for robot perception, yet implementing effective robot vision presents substantial challenges that continue to drive active research.

Cameras capture two-dimensional projections of three-dimensional scenes. A photograph loses depth information, projecting all objects onto a flat plane. This dimensionality reduction complicates many perception tasks. Two objects that appear the same size in an image might be identical objects at the same distance or different-sized objects at different distances. The camera cannot distinguish these cases from a single image. Many robot vision techniques focus on recovering lost depth information through various clever approaches.

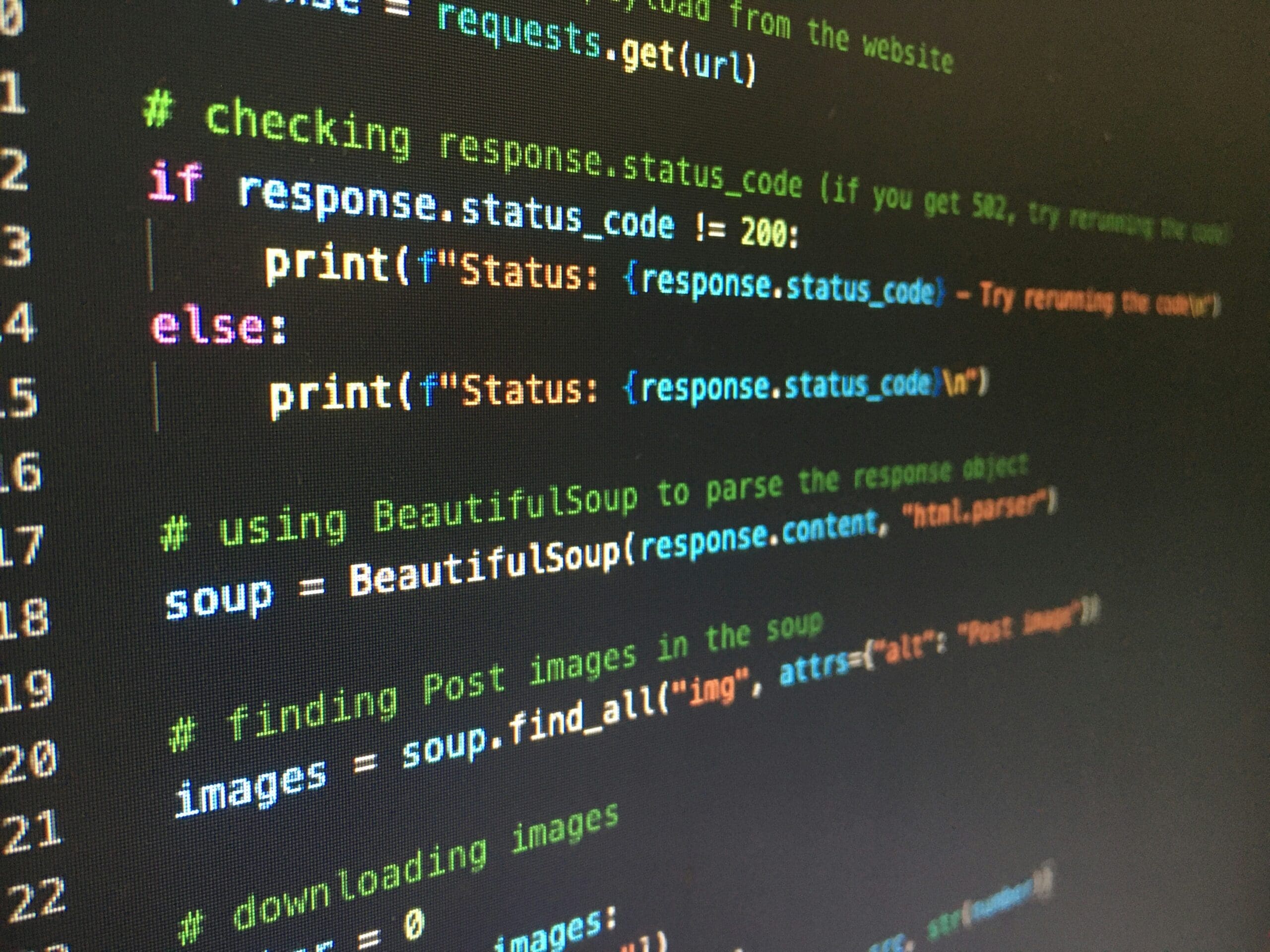

Color cameras use arrays of light-sensitive pixels, typically with color filters creating separate red, green, and blue channels. The pattern of light and dark across these millions of pixels forms images that sophisticated algorithms can analyze. Early robot vision systems used simple techniques like detecting edges or finding bright spots, but modern approaches increasingly employ machine learning, particularly deep neural networks, to recognize objects, segment images, and interpret scenes. These learning-based methods can achieve remarkable accuracy when trained on sufficient example images but require substantial computational power.

Monochrome cameras simplify by capturing only brightness information without color. While less information-rich than color images, monochrome cameras often provide better low-light performance and clearer images for certain applications. Many industrial vision systems use monochrome cameras because the lighting can be controlled and color rarely matters for quality inspection or part positioning tasks. The reduced data also processes faster, which matters for real-time applications.

Camera selection involves numerous technical considerations. Resolution determines how many pixels form each image, with higher resolution providing more detail but requiring more storage and processing. Frame rate specifies how many images the camera captures per second, with higher rates enabling robots to track fast-moving objects but generating more data to process. Lens selection affects field of view, depth of field, and image quality. Wide-angle lenses capture broad scenes but distort straight lines, while telephoto lenses provide narrow fields of view with less distortion.

Lighting dramatically affects camera performance in ways that human vision compensates for automatically but robots struggle with. Bright backlighting creates silhouettes where object details disappear. Shadows confuse algorithms designed to detect edges. Glossy surfaces create specular reflections that move as viewpoint changes. Successful robot vision systems often require careful lighting design, using controlled illumination to highlight features of interest while minimizing confusing shadows and reflections.

Stereo vision uses two cameras positioned like human eyes to recover depth information through triangulation. Objects closer to the cameras appear at different positions in left and right images than distant objects. Calculating these positional differences, called disparities, allows the system to estimate distance for each pixel. This approach provides dense depth maps showing distance to every visible surface, but it requires significant computation and struggles with textureless surfaces where matching corresponding points between left and right images becomes difficult.

Specialized vision systems extend beyond traditional cameras. Thermal cameras detect infrared radiation, revealing temperature differences invisible to normal cameras. This capability lets robots see in complete darkness, detect living things by their body heat, or identify hot components in machinery. Event cameras inspired by biological vision report only pixels where brightness changes rather than capturing complete frames, dramatically reducing data while capturing motion with exceptional temporal precision. Hyperspectral cameras capture many narrow wavelength bands beyond human-visible light, enabling applications like identifying materials by their spectral signatures.

Distance Measurement: Knowing How Far

While cameras provide rich visual information, many robotic tasks require accurate distance measurements to specific points or surfaces. Robots navigating environments need to know how far away obstacles sit. Robotic arms must measure distances to objects they need to grasp. Autonomous vehicles require precise ranging to maintain safe following distances. Numerous sensor technologies address this fundamental need to measure distance, each with distinct characteristics and appropriate applications.

Ultrasonic sensors operate like biological echolocation, emitting high-frequency sound pulses and measuring the time required for echoes to return. Sound travels at approximately 343 meters per second in air, so timing the round-trip gives distance. These sensors provide reliable distance measurements from a few centimeters to several meters, working regardless of lighting conditions and costing relatively little. The wide beam pattern means ultrasonic sensors measure distance to the nearest object within a cone rather than a precise point, which limits resolution but helps detect small obstacles that might be missed by narrower beams.

Temperature and humidity affect sound velocity, introducing errors if not compensated. Hard, smooth surfaces reflect ultrasound well, while soft or angled surfaces absorb or deflect sound away from the sensor, sometimes causing the sensor to miss objects. Despite limitations, ultrasonic sensors excel for basic obstacle detection in indoor robots, parking assistance systems, and level measurement in tanks.

Infrared proximity sensors measure distance using reflected light rather than sound. An infrared LED emits light that reflects off nearby objects back to a position-sensitive detector. The angle at which reflected light strikes the detector varies with distance, allowing the sensor to calculate how far away the object sits. These sensors respond faster than ultrasonic types and work well for detecting objects within a few centimeters to a meter or so. However, object color and surface finish strongly affect measurements because dark or non-reflective surfaces return little light while shiny surfaces create unpredictable reflections.

Laser rangefinders use focused laser beams to measure distances with high precision. Time-of-flight laser sensors measure the interval between emitting a laser pulse and detecting its reflection, similar to ultrasonic sensors but using light instead of sound. Light travels so fast that measuring these tiny time intervals requires sophisticated electronics, but the result provides centimeter or even millimeter accuracy across ranges from centimeters to hundreds of meters. The narrow laser beam measures distance to a specific point rather than a cone, providing directional precision that ultrasonic sensors lack.

LIDAR systems, an acronym for Light Detection and Ranging, extend laser rangefinding by rapidly scanning the laser beam across the environment to measure distances in many directions. A rotating mirror or the entire sensor assembly spins, sweeping the laser beam through 360 degrees while taking thousands of distance measurements per second. The result is a detailed map of distances to surfaces all around the robot. LIDAR enables robots to detect obstacles, map environments, and navigate complex spaces. Originally developed for specialized applications like autonomous vehicles and surveying, LIDAR sensors have become more affordable and compact, making them accessible for robotics projects.

Structured light systems project known light patterns onto surfaces and use cameras to observe how the pattern deforms based on surface shape. The projected pattern might be a grid of lines, a random dot pattern, or coded light stripes. Analyzing how these patterns appear in camera images reveals three-dimensional surface structure. This approach works well for detailed 3D scanning of objects or faces at close range. Many 3D scanners and some robot gripper systems use structured light for precise shape measurement.

Time-of-flight cameras combine distance measurement with imaging by measuring distance for each pixel simultaneously. Rather than scanning a single laser beam, these cameras illuminate the entire scene with modulated light and use specialized sensors to measure phase shifts in the reflected light at each pixel. The result is a depth image where each pixel’s value represents distance rather than brightness or color. These sensors provide dense depth maps at video rates, making them valuable for robots that need to quickly perceive three-dimensional scene geometry.

Touch and Force: Physical Interaction Sensing

While vision and distance sensing allow robots to perceive at a distance, many robotic tasks require physical contact with objects or surfaces. Touch sensing provides information available only through direct contact, complementing non-contact perception modalities. From simple switches that detect whether something is present to sophisticated force sensors that measure multi-axis forces and torques, contact sensing enables robots to interact with the physical world safely and effectively.

Limit switches and bumper switches represent the simplest contact sensors. A mechanical switch closes when physically pressed, sending a signal to the control system. Robot bumpers often incorporate multiple switches that trigger when the robot collides with obstacles, allowing reactive avoidance behaviors. Despite their simplicity, these binary sensors reliably detect contact and cost very little. Many mobile robots use bumper switches as backup sensors, providing a guaranteed last line of defense against collisions that other sensors might miss.

Pressure-sensitive resistors change their electrical resistance when pressed, allowing measurement of contact force rather than just presence or absence of contact. These sensors vary from simple force-sensing resistors that detect crude pressure levels to precision load cells that measure forces accurately. Applications range from robotic grippers that need to grasp firmly enough to hold objects without crushing them, to wheeled robots that measure ground contact forces to detect when they are stuck or tipping.

Force-torque sensors measure both linear forces and rotational torques in multiple axes, providing rich information about contact interactions. A six-axis force-torque sensor mounted at a robot wrist measures forces and torques in all directions, allowing the robot to feel what happens when it contacts surfaces or manipulates objects. This detailed force feedback enables sophisticated manipulation tasks like inserting parts that must align precisely, assembling components that require specific insertion forces, or safely interacting with humans through impedance control that yields when pushed.

Tactile sensor arrays embed multiple sensing elements in grids or patterns, creating artificial skin that can detect where contact occurs and the distribution of pressure across an area. Some designs use conductive materials separated by compressible spacers, measuring capacitance changes as pressure brings conductors closer. Others use arrays of tiny force sensors. Covering robot gripper fingers with tactile arrays allows the robot to feel object shape and detect slippage when grasped objects start to slide. Research into soft robotics increasingly incorporates distributed tactile sensing for gentle, adaptive interaction with delicate or irregular objects.

Proprioceptive sensors tell robots about their own body configuration and motion. While not strictly environmental sensing, proprioception proves essential for coordinated movement and manipulation. Joint encoders measure angles at articulated joints, telling robotic arms the precise configuration of all joints. Current sensors in motors provide information about torque and load. Accelerometers and gyroscopes in inertial measurement units track acceleration and rotation. This self-sensing allows robots to know what their bodies are doing, enabling precise control and detection of unexpected interactions like collisions or unexpected loads.

Sound: Acoustic Perception

Acoustic sensing receives less attention in robotics than vision or distance measurement, yet sound provides valuable information about the environment and enables important interaction modalities. Humans routinely use sound to detect events we cannot see, determine direction to sound sources, and communicate through speech. Robots can exploit similar capabilities when equipped with appropriate acoustic sensors and processing.

Microphones convert sound pressure waves into electrical signals that the control system can analyze. Simple applications use microphones to detect sound presence or measure volume. A robot might respond to claps or loud noises as command inputs. Volume-based sound detection requires minimal processing but provides limited information beyond whether sounds occurred and roughly how loud they were.

Frequency analysis reveals much more about sounds. Examining which frequencies are present distinguishes different sound types. Motors produce characteristic frequency patterns related to their rotation speed. Mechanical failures often generate distinct acoustic signatures. Voice commands contain frequency patterns that speech recognition algorithms can interpret. Frequency analysis through Fourier transforms or similar techniques extracts this information, enabling robots to distinguish sound types and respond appropriately to different acoustic events.

Microphone arrays using multiple microphones at known positions enable sound source localization. Sound reaches microphones at slightly different times depending on source location. Analyzing these time differences allows calculating the direction to the sound source. Four or more microphones arranged three-dimensionally can localize sounds in space. Applications include attention mechanisms that orient robots toward speakers, surveillance systems that detect direction to disturbances, and user interfaces that respond to voice commands from specific locations.

Speech recognition transforms spoken language into text or commands that robots can act upon. Modern deep learning approaches achieve impressive accuracy for speech recognition, making voice control increasingly practical for robotic applications. Users can command robots through natural language rather than requiring buttons, remote controls, or programming. Speech recognition challenges include handling diverse accents, operating in noisy environments, and distinguishing target speech from background conversations.

Speaker recognition identifies who is speaking based on voice characteristics, enabling robots to respond differently to different users. Combined with speech recognition, this allows personalized interaction where robots remember individual preferences or permissions. Security applications might restrict certain commands to authorized users identified by voice.

Acoustic environmental analysis characterizes spaces through sound. The pattern of echoes and reverberations reveals room size, surface materials, and geometry. Research explores using sound to navigate or map environments, though vision and laser ranging currently dominate for these applications. However, sound propagates around corners and through materials that block light, providing complementary information to visual sensing in some scenarios.

Chemical and Environmental Sensing

Robots operating in real-world environments often need to measure environmental conditions beyond visual and spatial information. Temperature, humidity, air quality, and chemical composition affect both robot operation and the tasks robots perform. Specialized sensors detect these environmental properties, enabling robots to respond to conditions invisible to cameras or distance sensors.

Temperature sensors measure thermal conditions using various physical principles. Thermistors change resistance with temperature, providing simple, inexpensive measurement. Thermocouples generate voltage proportional to temperature differences, working across extreme temperature ranges. Infrared temperature sensors measure thermal radiation to determine surface temperatures without contact. Applications range from monitoring robot component temperatures to prevent overheating, to environmental robots that map temperature distributions, to industrial robots that must handle hot materials.

Humidity sensors detect moisture content in air, important for applications in agriculture, environmental monitoring, and climate control. Capacitive humidity sensors change electrical properties based on absorbed moisture. Resistive types change resistance as humidity varies. Knowing humidity helps agricultural robots optimize irrigation, environmental monitoring robots assess conditions, and industrial robots operate in appropriate atmospheric conditions.

Gas sensors detect specific chemicals in air through various sensing mechanisms. Electrochemical sensors generate current proportional to target gas concentration. Metal oxide sensors change resistance when exposed to certain gases. Photoionization detectors measure gases through ionization under UV light. Applications include safety monitoring for toxic gases, air quality assessment for pollutants, and specialized tasks like wine production quality control where robots monitor fermentation gases.

Barometric pressure sensors measure atmospheric pressure, useful for altitude estimation in flying robots and weather monitoring in environmental robots. Changes in pressure indicate altitude changes with several-meter precision, complementing GPS and accelerometer-based altitude estimation. Weather monitoring applications use pressure trends to predict weather changes.

Particulate matter sensors detect airborne particles like dust, pollen, or pollution. These increasingly important sensors help robots monitor air quality, important for environmental awareness and human health. Optical particle counters shine light through air samples and detect scattered light from particles. Mass-based sensors measure particle mass concentrations.

Water quality sensors enable underwater and environmental robots to assess aquatic conditions. Conductivity sensors measure dissolved ion concentration. Dissolved oxygen sensors quantify oxygen available to aquatic life. pH sensors measure acidity or alkalinity. Turbidity sensors detect suspended particles that cloud water. These sensors support applications from environmental monitoring to aquaculture management to water treatment.

Sensor Fusion: Combining Multiple Modalities

Individual sensors provide valuable but incomplete information about environments. Ultrasonic sensors measure distance but not object identity. Cameras show what things look like but not precisely how far away they are. Each sensor type has strengths and weaknesses, blind spots and failure modes. Sophisticated robots combine multiple sensor types in sensor fusion approaches that provide more complete, reliable perception than any single sensor could achieve.

Complementary sensor fusion combines sensors that measure different environmental aspects. A mobile robot might use cameras for object recognition, LIDAR for precise distance measurement, and bumper switches for contact detection. Each sensor contributes unique information, and together they create comprehensive environmental awareness. If the camera identifies an object as a doorway but LIDAR shows no opening, the robot knows the door is closed. If LIDAR detects an opening but cameras show different surroundings, the robot recognizes it has entered a new room.

Redundant sensor fusion uses multiple sensors measuring the same thing to improve reliability and accuracy. Two ultrasonic sensors pointing in the same direction can verify each other’s readings, detecting sensor failures or environmental conditions that confuse one sensor. Averaging readings from multiple sensors reduces random noise. Comparing readings can identify and reject outlier measurements caused by interference or reflections.

Multi-modal fusion creates unified representations from fundamentally different sensor types. Autonomous vehicles combine camera images showing lane markings and signs with LIDAR point clouds showing three-dimensional geometry and radar measurements providing velocity information. Advanced fusion algorithms align these different data types spatially and temporally, creating coherent environmental models that exploit each sensor’s strengths while compensating for weaknesses.

Temporal fusion integrates sensor readings over time to build better understanding than single-moment snapshots provide. Kalman filters and particle filters represent classic approaches that combine new sensor measurements with predictions based on previous measurements and motion models. These filters reduce sensor noise, handle missing data when sensors temporarily fail to detect things, and enable tracking moving objects by predicting where they will be between measurements.

Fusion algorithms must handle sensor calibration, ensuring that measurements from different sensors align properly. A robot fusing camera and LIDAR data must know precisely how the camera and LIDAR relate spatially so that features seen in camera images correspond correctly to LIDAR distance measurements. Calibration procedures determine these spatial relationships, often by observing known targets with multiple sensors and calculating transformations that align the data.

Fusion also addresses synchronization, ensuring that combined sensor readings actually correspond to the same moment in time. If sensors sample at different rates or have different processing delays, raw timestamp data may not align. Careful synchronization ensures the camera image, LIDAR scan, and IMU reading being fused actually describe the same environmental state rather than measurements separated by motion or environmental changes.

Limitations and the Reality Gap

Understanding robot perception requires honestly acknowledging significant limitations compared to biological sensing. Human perception operates effortlessly in conditions where robots struggle. We recognize familiar faces across varying lighting, distinguish objects partly hidden by clutter, and hear conversations in noisy environments. Robots can surpass human sensing in narrow domains like measuring exact distances or seeing infrared radiation, but general perceptual robustness remains challenging.

Lighting sensitivity affects vision systems dramatically. Cameras optimized for indoor lighting saturate in bright sunlight. Those tuned for outdoor use capture too-dark indoor images. Humans adapt effortlessly across six orders of magnitude in brightness, while camera sensors cover perhaps three orders before requiring adjustment. Robot vision in variable lighting remains an active research area despite decades of work.

Occlusion, where objects hide behind other objects, confuses many perception systems. Humans infer hidden object parts from experience and context, but robots must work with visible information. A person partly hidden behind a wall appears clearly as a person to human observers, but computer vision might see disconnected body parts or fail to detect the person entirely.

Adversarial conditions can fool perception systems in ways humans resist. Slightly altered camera inputs can cause neural networks to wildly misclassify objects, seeing stop signs as speed limit signs or pedestrians as empty road. Shiny surfaces confuse distance sensors with false reflections. These failure modes require defensive design acknowledging perceptual limitations.

Processing requirements for sophisticated perception can exceed available computational resources. Deep learning vision models achieving human-like object recognition require substantial processing power, more than small robot controllers can provide. This drives research into efficient models and specialized hardware accelerators, but computational constraints continue to limit what perception algorithms robots can run in real time.

The gap between laboratory and real-world performance affects deployed robots. Perception systems work well in controlled test environments but struggle with real-world diversity, unpredictability, and edge cases. This reality gap drives emphasis on robust algorithms, diverse training data, and careful validation across operating conditions the robot will actually encounter.

The Path Forward in Robot Perception

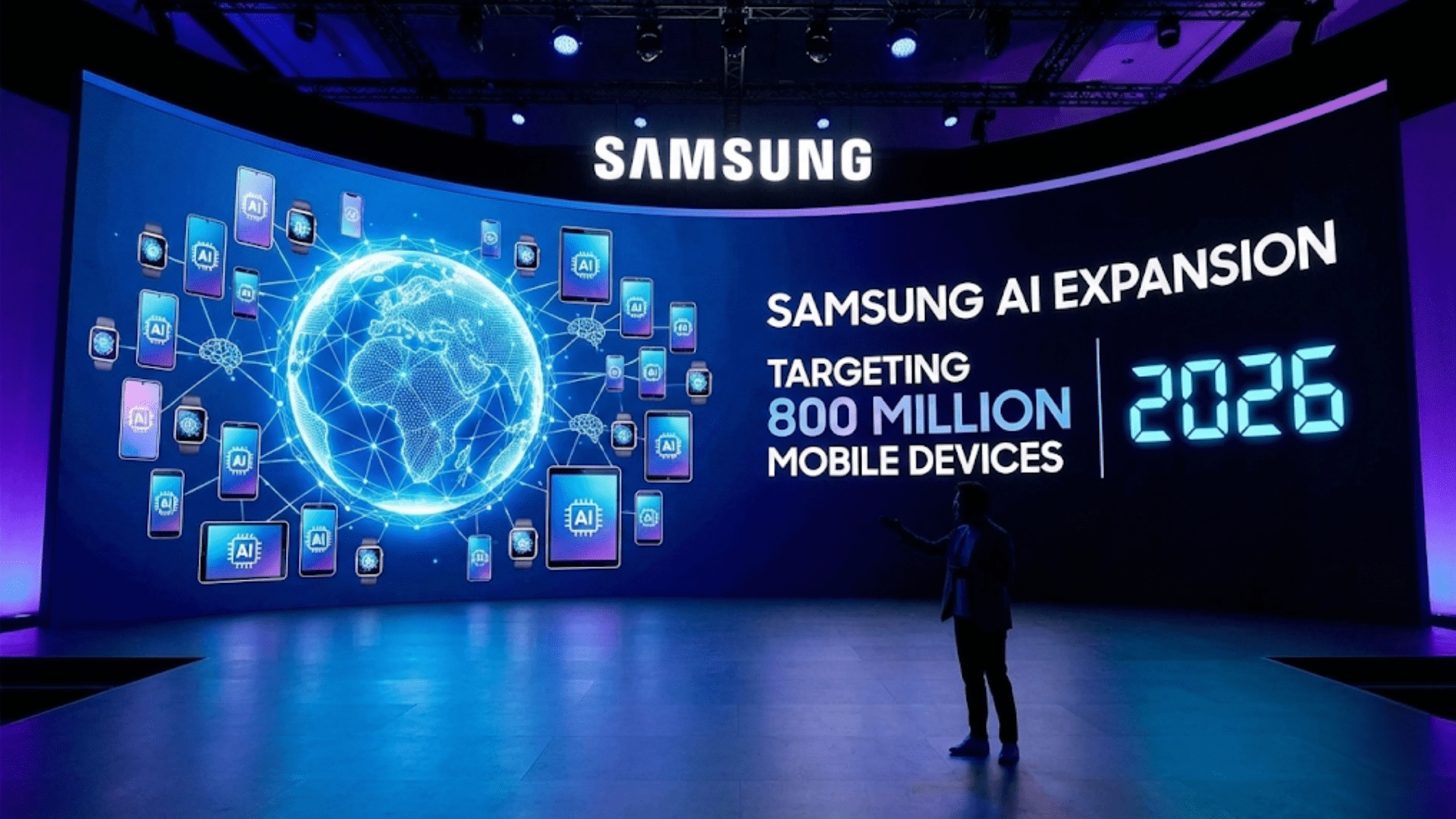

Despite current limitations, robot perception capabilities have improved dramatically and continue advancing rapidly. Modern robots perceive environments with sophistication unimaginable decades ago. Machine learning, especially deep neural networks, has revolutionized vision and acoustic processing. Sensors have become more capable, affordable, and compact. Fusion algorithms combine multiple modalities effectively. These advances enable applications from autonomous vehicles to warehouse robots to surgical assistants.

Your robot perception designs should match sensors to your specific tasks and constraints. Simple applications may need only basic sensors and processing. Complex tasks might require sophisticated multi-modal fusion. Understanding available sensor types, their characteristics and limitations, and how they can be combined guides you toward effective perceptual systems for your robots. Each sensor choice involves tradeoffs between cost, accuracy, range, field of view, and processing requirements. Successful robot perception comes from thoughtfully matching these characteristics to what your robot needs to accomplish in its actual operating environment.

Robot perception transforms physical phenomena into digital information that control systems can process and act upon. From cameras providing rich visual data to ultrasonic sensors measuring distances to force sensors detecting contact, these perceptual capabilities enable robots to operate in and respond to real environments. Understanding how robots sense – the physical principles sensors exploit, the information they provide, and their limitations – equips you to design effective perception systems for your own robots and appreciate the sophisticated sensing that enables modern robotic applications.