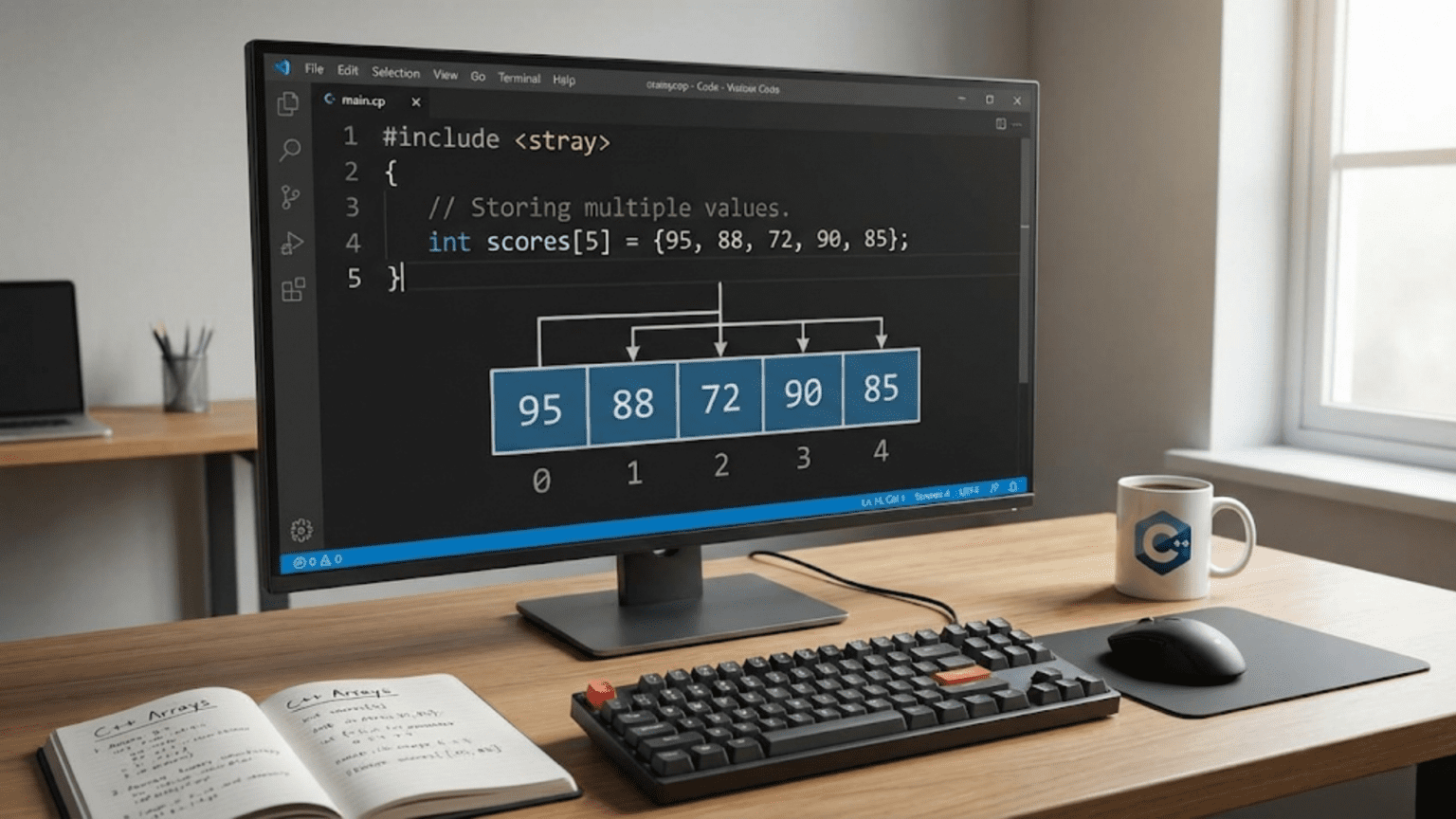

Imagine you’re writing a program that needs to store the test scores for thirty students in a class. You could create thirty separate variables—score1, score2, score3, and so on—but this approach quickly becomes unwieldy and impractical. What if you need to calculate the average score? You’d have to write a massive expression adding all thirty variables together. What if the class size changes to forty students? You’d need to add ten more variables and rewrite all your code. This is exactly the problem that arrays solve.

An array is a collection of variables of the same type, stored in contiguous memory locations and accessed using a single name. Instead of managing thirty individual variables, you create one array that holds thirty values. Each value occupies a numbered position called an index, and you access individual values by specifying which index you want. Arrays transform how you work with collections of related data, making it possible to process large amounts of information efficiently using loops and other programming constructs.

Understanding arrays represents a significant milestone in your programming journey. Arrays are fundamental data structures that appear in virtually every program of any complexity. They serve as the foundation for more advanced data structures you’ll learn later, and mastering arrays now prepares you for understanding these more sophisticated concepts. Let me walk you through arrays systematically, building your understanding from basic principles to practical applications.

The most basic form of array declaration specifies the type of elements the array will hold and how many elements it can store:

int scores[5]; // Array that holds 5 integersThis declaration creates an array named scores that can store five integer values. The number in square brackets is the array’s size—how many elements it contains. Once you declare an array with a specific size, that size is fixed and cannot change during program execution. This fixed size distinguishes arrays from more flexible data structures you’ll encounter later, but it also makes arrays efficient and predictable.

The elements in an array are numbered starting from zero, not one. This zero-based indexing is a convention that C++ inherits from C and that most modern programming languages follow. The first element is at index zero, the second element is at index one, and so on. An array of five elements has valid indices from zero to four. This indexing scheme can confuse beginners at first, but it becomes second nature with practice and actually has mathematical elegance that makes certain calculations simpler.

You access individual array elements using square brackets with the index:

scores[0] = 95; // Set the first element to 95

scores[1] = 87; // Set the second element to 87

scores[2] = 92; // Set the third element to 92

scores[3] = 78; // Set the fourth element to 78

scores[4] = 88; // Set the fifth element to 88

std::cout << "First score: " << scores[0] << std::endl;

std::cout << "Third score: " << scores[2] << std::endl;Each array element behaves exactly like a regular variable of the array’s type. You can read from it, write to it, use it in expressions, pass it to functions—anything you can do with a regular variable works with array elements.

Array initialization lets you set initial values when you declare the array, avoiding the need to assign each element individually:

int scores[5] = {95, 87, 92, 78, 88}; // Initialize all five elementsThe values inside the curly braces are assigned to array elements in order: the first value goes to index zero, the second to index one, and so on. This initialization syntax makes it easy to create arrays with known starting values.

If you provide fewer initializers than the array size, the remaining elements are set to zero:

int numbers[5] = {1, 2, 3}; // Elements 0-2 are 1,2,3; elements 3-4 are 0You can even omit the size when providing initializers, and the compiler deduces the size from the number of values:

int scores[] = {95, 87, 92, 78, 88}; // Compiler determines size is 5This implicit sizing works only when you provide initial values. The compiler counts the initializers and creates an array of that size. While convenient, explicitly specifying the size often makes your code clearer about its intentions.

To initialize all elements to zero, you can use empty braces:

int numbers[100] = {}; // All 100 elements set to 0This provides a concise way to zero-initialize large arrays without typing out all the zeros.

Let me show you a practical example that demonstrates basic array usage—a program that calculates the average of test scores:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int scores[5] = {95, 87, 92, 78, 88};

int sum = 0;

// Calculate sum of all scores

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

sum += scores[i];

}

// Calculate and display average

double average = static_cast<double>(sum) / 5;

std::cout << "Average score: " << average << std::endl;

return 0;

}This program demonstrates a fundamental pattern you’ll use constantly with arrays: looping through all elements to perform some operation. The loop variable i serves as the index, starting at zero and continuing while i is less than the array size. Inside the loop, scores[i] accesses each element in turn, and we accumulate them in the sum variable.

Notice that the loop condition is i less than five, not i less than or equal to five. This is crucial because valid indices range from zero to four. Using i less than or equal to five would attempt to access scores[5], which doesn’t exist, causing undefined behavior—your program might crash, might produce garbage results, or might appear to work but corrupt other data in memory. Staying within valid index bounds is essential when working with arrays.

The size of an array often needs to be stored in a variable or constant so you can refer to it in multiple places without hard-coding numbers:

const int SIZE = 5;

int scores[SIZE];

for (int i = 0; i < SIZE; i++) {

scores[i] = 0; // Initialize all elements

}Using a named constant for the size makes your code more maintainable. If you need to change the array size later, you modify only the constant declaration, and all the code that uses SIZE automatically adapts to the new size.

Modern C++ provides a better way to determine an array’s size at compile time using the sizeof operator:

int scores[] = {95, 87, 92, 78, 88};

int arraySize = sizeof(scores) / sizeof(scores[0]);The sizeof operator returns the number of bytes a variable occupies. sizeof(scores) gives the total bytes occupied by the entire array, while sizeof(scores[0]) gives the bytes occupied by one element. Dividing the total by the element size gives the number of elements. This technique works because the compiler knows the array’s size at compile time.

However, this technique has limitations and can produce incorrect results in certain situations, particularly when passing arrays to functions. In modern C++ (C++11 and later), the standard library provides a safer alternative:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int scores[] = {95, 87, 92, 78, 88};

// Modern C++ way to iterate

for (int score : scores) {

std::cout << score << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

return 0;

}This range-based for loop automatically iterates through all elements without needing to track indices. The loop variable score takes on each element’s value in turn. This syntax is clearer, less error-prone, and works correctly with various container types, not just arrays.

Arrays and loops work together naturally. Many array operations involve processing every element, which loops handle perfectly:

// Find the maximum value

int scores[] = {95, 87, 92, 78, 88};

int max = scores[0]; // Assume first element is maximum

for (int i = 1; i < 5; i++) {

if (scores[i] > max) {

max = scores[i];

}

}

std::cout << "Highest score: " << max << std::endl;This pattern initializes max with the first element, then compares each subsequent element to the current maximum, updating max whenever it finds a larger value. Notice the loop starts at index one instead of zero because we already used the first element to initialize max.

Searching for a specific value in an array is another common operation:

int scores[] = {95, 87, 92, 78, 88};

int searchValue = 92;

bool found = false;

int position = -1;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

if (scores[i] == searchValue) {

found = true;

position = i;

break; // Found it, no need to keep searching

}

}

if (found) {

std::cout << "Found " << searchValue << " at index " << position << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << searchValue << " not found in array" << std::endl;

}The loop examines each element until it finds the target value. The break statement exits the loop immediately when found, avoiding unnecessary comparisons after we’ve located what we’re searching for.

Passing arrays to functions requires understanding how C++ handles arrays differently from regular variables. When you pass an array to a function, you’re actually passing the memory address of the first element, not a copy of the entire array. This means the function can modify the original array’s elements:

void printArray(int arr[], int size) {

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

std::cout << arr[i] << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

}

void doubleValues(int arr[], int size) {

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

arr[i] *= 2; // Modifies original array

}

}

int main() {

int numbers[] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

printArray(numbers, 5); // Prints: 1 2 3 4 5

doubleValues(numbers, 5);

printArray(numbers, 5); // Prints: 2 4 6 8 10

return 0;

}Notice that when declaring array parameters, you can omit the size between the brackets—the function doesn’t know the array’s size unless you tell it, which is why we pass the size as a separate parameter. This lack of size information is why you typically need to pass the array size along with the array itself.

The fact that arrays are passed by reference (not by value like regular variables) has important implications. Functions can modify the caller’s array, which is sometimes desirable for efficiency (no need to copy large amounts of data) but can also lead to unexpected modifications if you’re not careful. If you want to prevent a function from modifying an array, use the const keyword:

void printArray(const int arr[], int size) {

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

std::cout << arr[i] << " ";

}

// arr[i] = 0; // Compiler error - can't modify const array

std::cout << std::endl;

}The const qualifier tells the compiler that the function promises not to modify the array, and the compiler enforces this promise by generating errors if the function tries to change any elements.

Multidimensional arrays extend the concept to multiple dimensions, most commonly two dimensions to represent tables, grids, or matrices:

int matrix[3][4]; // 3 rows, 4 columns - total of 12 elementsThis creates a two-dimensional array with three rows and four columns. You access elements using two indices—the first for the row, the second for the column:

matrix[0][0] = 1; // Top-left element

matrix[0][1] = 2;

matrix[0][2] = 3;

matrix[0][3] = 4;

matrix[1][0] = 5; // Second row, first columnInitializing multidimensional arrays uses nested braces:

int matrix[3][4] = {

{1, 2, 3, 4}, // First row

{5, 6, 7, 8}, // Second row

{9, 10, 11, 12} // Third row

};The outer braces contain the entire array, while inner braces group elements by row. This visual structure makes the array’s layout clear.

Processing multidimensional arrays requires nested loops—one loop for rows, another for columns:

int matrix[3][4] = {

{1, 2, 3, 4},

{5, 6, 7, 8},

{9, 10, 11, 12}

};

// Print the matrix

for (int row = 0; row < 3; row++) {

for (int col = 0; col < 4; col++) {

std::cout << matrix[row][col] << "\t";

}

std::cout << std::endl; // New line after each row

}The outer loop iterates through rows, and for each row, the inner loop iterates through all columns. This pattern accesses every element in row-major order—all elements of the first row, then all elements of the second row, and so on.

Let me show you a practical application of two-dimensional arrays—storing and analyzing student grades:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

const int STUDENTS = 4;

const int TESTS = 3;

// Each row is a student, each column is a test score

int grades[STUDENTS][TESTS] = {

{85, 92, 78}, // Student 0

{90, 88, 95}, // Student 1

{76, 81, 72}, // Student 2

{95, 89, 91} // Student 3

};

// Calculate and display average for each student

for (int student = 0; student < STUDENTS; student++) {

int sum = 0;

for (int test = 0; test < TESTS; test++) {

sum += grades[student][test];

}

double average = static_cast<double>(sum) / TESTS;

std::cout << "Student " << student << " average: " << average << std::endl;

}

// Calculate and display average for each test

std::cout << "\nTest averages:" << std::endl;

for (int test = 0; test < TESTS; test++) {

int sum = 0;

for (int student = 0; student < STUDENTS; student++) {

sum += grades[student][test];

}

double average = static_cast<double>(sum) / STUDENTS;

std::cout << "Test " << test << " average: " << average << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}This program demonstrates how two-dimensional arrays naturally represent tabular data. The first set of loops calculates each student’s average by iterating across columns (tests) for each row (student). The second set calculates each test’s average by iterating down rows (students) for each column (test). The ability to access data by different dimensions makes multidimensional arrays powerful for organizing related information.

Common mistakes with arrays often involve index boundaries. Accessing an index outside the valid range causes undefined behavior:

int numbers[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

// WRONG - index 5 is out of bounds (valid indices: 0-4)

numbers[5] = 6; // Undefined behavior!

// WRONG - negative index

numbers[-1] = 0; // Undefined behavior!C++ doesn’t automatically check array bounds for you—accessing invalid indices won’t generate a compiler error and might not even crash your program. Instead, you might silently corrupt other variables or data, causing bugs that are difficult to track down. Always ensure your indices stay within valid bounds.

Another common mistake is forgetting that array size is fixed:

int scores[5];

// Can't resize the array later

// Can't add a 6th elementIf you need a collection that can grow or shrink, you’ll want to use std::vector, which you’ll learn about later. Arrays are appropriate when you know the size at compile time and it won’t change.

Uninitialized arrays contain garbage values:

int numbers[5]; // Elements contain random values!

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

std::cout << numbers[i] << " "; // Prints unpredictable values

}Always initialize arrays before using their values, either through initialization syntax or by explicitly assigning values in your code.

The relationship between arrays and pointers, while important, can be confusing for beginners. When you use an array’s name without brackets, it converts to a pointer to the first element:

int numbers[] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

int* ptr = numbers; // numbers converts to pointer to first element

// These are equivalent:

std::cout << numbers[0] << std::endl; // Array indexing

std::cout << *ptr << std::endl; // Pointer dereferencingUnderstanding this relationship helps explain why arrays passed to functions can be modified—you’re passing a pointer to the array’s data, not a copy of the array itself.

Character arrays deserve special mention because they’re commonly used to store strings in C-style programming:

char name[20] = "Alice"; // C-style stringA character array holding a string must include a null terminator (‘\0’) at the end to mark where the string stops. Many C string functions rely on this null terminator to know when they’ve reached the end of the string. Modern C++ provides std::string, which is generally preferred for string handling because it manages memory automatically and provides safer, more convenient operations. However, you’ll encounter C-style character arrays in legacy code and when interfacing with certain libraries.

Let me show you a more comprehensive example that brings together many array concepts—a program that manages a simple inventory system:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

const int MAX_ITEMS = 10;

void displayInventory(std::string names[], int quantities[], int count) {

std::cout << "\nCurrent Inventory:" << std::endl;

std::cout << "==================" << std::endl;

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

std::cout << names[i] << ": " << quantities[i] << std::endl;

}

}

int findItem(std::string names[], int count, std::string searchName) {

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

if (names[i] == searchName) {

return i; // Return index where found

}

}

return -1; // Return -1 if not found

}

void updateQuantity(std::string names[], int quantities[], int count) {

std::string itemName;

int adjustment;

std::cout << "Enter item name: ";

std::cin >> itemName;

int index = findItem(names, count, itemName);

if (index == -1) {

std::cout << "Item not found!" << std::endl;

return;

}

std::cout << "Enter quantity change (positive to add, negative to remove): ";

std::cin >> adjustment;

quantities[index] += adjustment;

if (quantities[index] < 0) {

quantities[index] = 0; // Don't allow negative quantities

}

std::cout << "Updated " << itemName << " to " << quantities[index] << std::endl;

}

int main() {

// Parallel arrays - same index refers to same item

std::string itemNames[MAX_ITEMS] = {"Apples", "Oranges", "Bananas"};

int itemQuantities[MAX_ITEMS] = {50, 30, 25};

int itemCount = 3;

displayInventory(itemNames, itemQuantities, itemCount);

updateQuantity(itemNames, itemQuantities, itemCount);

displayInventory(itemNames, itemQuantities, itemCount);

return 0;

}This program demonstrates several important array techniques. It uses parallel arrays—multiple arrays where the same index in each array refers to related data about the same entity. The displayInventory function shows how to pass multiple arrays to a function. The findItem function demonstrates searching an array and returning the index where an item is found. The updateQuantity function modifies array elements based on user input.

While this example uses parallel arrays to keep things simple, in practice you’d typically use structures (which you’ll learn about later) to group related data together more naturally. The parallel array technique works but becomes unwieldy as the number of related pieces of data grows.

Key Takeaways

Arrays store multiple values of the same type in contiguous memory, accessed through zero-based indices. Declaring an array specifies its type and size, which is fixed and cannot change after declaration. Array initialization can be done at declaration time using curly braces, and you can let the compiler deduce the size when providing initializers. Always ensure your array indices stay within valid bounds—from zero to size minus one—as C++ doesn’t check bounds automatically.

Arrays and loops work together naturally for processing collections of data. Common operations include calculating sums and averages, finding maximum or minimum values, searching for specific elements, and transforming data. When passing arrays to functions, remember that arrays are passed by reference, meaning functions can modify the original array’s elements. Use const to prevent modifications when appropriate.

Multidimensional arrays extend to two or more dimensions using nested brackets, with nested loops required to process all elements. Character arrays can store strings but require careful handling of null terminators. Modern C++ provides alternatives like std::string and std::vector that offer additional safety and convenience, but understanding basic arrays remains essential as they form the foundation for these more sophisticated structures.