Introduction

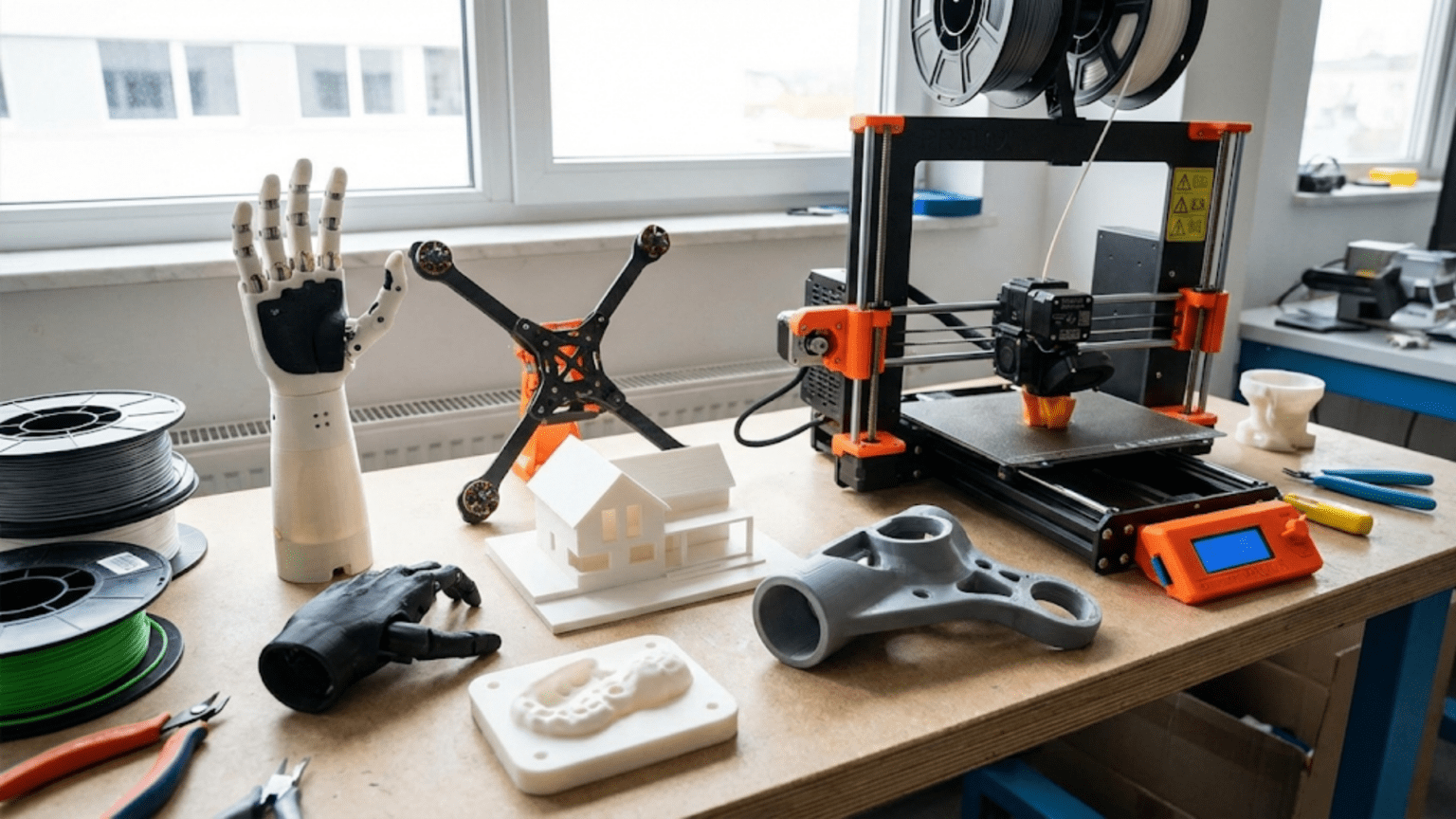

When people first encounter three-dimensional printing technology, one of the most common questions they ask is deceptively simple: “What can you actually make with this?” The question reveals both curiosity about the technology’s practical capabilities and skepticism about whether 3D printing produces anything beyond novelty items and plastic trinkets. This skepticism is understandable given how media coverage often focuses on either futuristic possibilities like printing houses or organs, or showcases artistic sculptures and whimsical toys that appear more decorative than functional.

The reality of what three-dimensional printing can produce spans an enormous spectrum from those novelty items to mission-critical aerospace components, from prototype concepts that exist only briefly during product development to finished medical devices used inside human bodies, from replacement parts that cost pennies to manufacture custom components that would cost thousands through traditional methods. Understanding this range of applications requires moving beyond simple categorization into “toys versus serious parts” and instead examining how different industries, organizations, and individuals leverage additive manufacturing’s unique capabilities to solve specific problems or create particular value.

The applications that make the most sense for 3D printing generally share certain characteristics that align with the technology’s strengths. Projects requiring rapid iteration benefit from the speed of printing revised designs. Applications demanding customization leverage the ability to modify each unit without tooling costs. Situations where complex geometries provide functional advantages exploit the design freedom additive manufacturing enables. Use cases involving small production volumes capitalize on the elimination of minimum order quantities. Understanding these patterns helps reveal not just what can be made but what should be made with 3D printing versus traditional manufacturing.

This comprehensive exploration of real-world 3D printing applications will take you through diverse industries and use cases, from prototyping and product development through manufacturing tooling, from medical and dental applications through aerospace and automotive components, from educational tools through consumer products and household items. You will discover how the technology solves problems across this spectrum and gain insight into what makes certain applications particularly well-suited to additive manufacturing. By the end, you will understand not only the breadth of what 3D printing can produce but also the underlying principles that determine when it provides genuine value versus when traditional methods remain superior.

Prototyping and Product Development

Perhaps the single most widespread professional application of three-dimensional printing occurs in the realm of prototyping and product development. Companies across virtually every industry use 3D printing to transform digital designs into physical models that can be held, tested, and evaluated before committing to expensive production tooling or manufacturing setup. This application leverages several of additive manufacturing’s core strengths simultaneously while avoiding many of its limitations.

The speed advantage for prototyping proves decisive in compressed development timelines. Traditional prototype manufacturing might require weeks for a machine shop to program CNC operations, set up fixtures, and produce parts. Creating injection mold tooling, even temporary prototype-grade soft tooling, adds weeks or months to timelines. With 3D printing, designers can complete a CAD model in the morning and have physical prototypes in hand the next morning. This rapid turnaround compresses the design iteration cycle from weeks per iteration to days or even hours, allowing many more design variations to be explored within the same overall project timeline.

The cost structure for prototype quantities strongly favors additive manufacturing. Creating a single prototype part through traditional manufacturing might cost hundreds or thousands of dollars when accounting for setup time, programming, and the minimum charges that shops impose for small quantities. That same part might cost ten to fifty dollars in material and machine time when 3D printed, a difference of one to two orders of magnitude. For product development budgets where multiple iterations across dozens of components add up quickly, this cost advantage can be substantial.

The complexity independence of additive manufacturing particularly benefits prototyping because product designers often explore intricate details, organic shapes, or integrated features that would be expensive to prototype through traditional methods. A design iteration might add internal channels for routing wires, integrate clips and snap-fits, or incorporate complex curved surfaces. Traditional prototype manufacturing would charge significantly more for these complex features. 3D printing produces them in essentially the same time and cost as simpler geometries, removing the economic pressure to simplify prototypes in ways that might compromise design validation.

Form-fit-function prototyping represents different validation stages that benefit from 3D printing to varying degrees. Form prototypes validate appearance, proportions, and how components relate visually. These need accurate external geometry but do not require functional materials or working mechanisms. Three-dimensional printing excels at form prototypes by quickly producing accurate shapes in a range of finish qualities depending on the printing technology used. SLA or material jetting produces smooth surfaces suitable for presentation models, while FDM provides adequate surface quality for design validation at lower cost.

Fit prototypes validate how components assemble together, clearances between parts, and dimensional accuracy of mating features. These require accurate dimensions and realistic material properties to assess whether assembly will work as intended. Three-dimensional printing handles fit prototypes well when tolerances are not extremely tight, typically within a few tenths of a millimeter. Designers learn to account for the dimensional capabilities of their specific printing technology and adjust tolerances in early designs accordingly.

Function prototypes must perform mechanically like production parts to validate that the design will work when manufactured. Material properties become critical here, and additive manufacturing faces limitations. The anisotropic properties of FDM printing mean parts may be weaker than injection-molded equivalents. Layer adhesion can fail under loads that production parts would survive. For functional testing where mechanical performance under load matters, designers must carefully consider whether printed prototypes will provide valid test results or whether other prototyping methods like CNC machining from production materials or cast urethane parts from printed masters provide better validation.

User testing and ergonomic evaluation represent another important prototyping application where 3D printing adds value. When developing consumer products, medical devices, or tools that people will physically interact with, having prototypes to place in users’ hands provides invaluable feedback about size, shape, grip, button placement, and overall usability. The ability to rapidly print variations based on initial feedback allows iterative refinement through multiple user test cycles within compressed timelines. A product development team might test five different handle shapes in one week by printing each version overnight and conducting user sessions the next day.

Design communication benefits enormously from physical prototypes compared to digital models or drawings. Communicating a design concept to stakeholders, investors, or customers becomes much more effective when they can hold and examine a physical object rather than interpreting technical drawings or rotating a CAD model on a screen. The tangibility helps non-technical stakeholders understand the design intent and provide meaningful feedback. Many successful crowdfunding campaigns feature 3D printed prototypes that help potential backers visualize the product in ways that renderings alone cannot achieve.

Market testing and pre-production validation sometimes use 3D printed parts when production tooling requires substantial investment. Companies can produce small quantities of parts for beta testing, focus groups, or limited market trials using additive manufacturing, gathering real-world feedback before committing to production tooling. If the market response indicates design changes are needed, no expensive tooling gets scrapped. The financial risk of bringing new products to market decreases when prototype quantities can test market reception before final design freeze and tooling investment.

Medical and Dental Applications

Healthcare represents one of the most rapidly growing application areas for three-dimensional printing, with the technology’s ability to create patient-specific customized devices proving particularly valuable in contexts where individual anatomical variation matters significantly. The applications span from planning and educational models through surgical guides and custom implants, with regulatory pathways increasingly well-established for many device categories.

Anatomical models printed from patient medical imaging data provide surgeons with tangible representations of specific patient anatomy for surgical planning. When a neurosurgeon faces a complex tumor removal, having a physical model of that patient’s skull with the tumor precisely located allows planning the surgical approach, identifying critical structures to avoid, and even practicing the procedure before entering the operating room. These models can show pathology in three dimensions with spatial relationships that are difficult to fully appreciate from screen images or two-dimensional scans.

The workflow for creating these models begins with CT or MRI scans that capture the patient’s anatomy as digital volumetric data. Specialized software segments this data to isolate structures of interest like bones, blood vessels, or tumors. The segmented data converts to 3D printable models that can be manufactured in various materials depending on the application. Hard bone structure might print in rigid resin or nylon, while soft tissue could use flexible materials to better represent actual tissue properties. Some models incorporate multiple materials or colors to differentiate anatomical structures.

Surgical guides represent another important medical application where 3D printing provides clear value. These patient-specific guides position on the patient during surgery to direct cutting tools, drill bits, or implant placement with precision that would be difficult to achieve through freehand technique. Orthopedic surgeries use guides to precisely position bone cuts for joint replacements. Dental implant surgeries use guides to drill pilot holes at correct angles and depths determined through digital planning. The ability to manufacture these guides customized to each patient’s anatomy for reasonable cost makes precision techniques accessible that would otherwise require expensive navigation systems.

Custom prosthetics and orthotics benefit from 3D printing’s customization capabilities and design freedom. Traditional prosthetic sockets require extensive manual fabrication by skilled prosthetists, using processes that can take weeks and require multiple patient visits for fitting adjustments. Digital scanning of residual limbs combined with 3D printing allows creating custom sockets that match the limb geometry precisely, potentially improving comfort and function. The ability to iterate on designs through printing test sockets before final production helps achieve optimal fit more quickly than traditional fabrication methods.

Hearing aids represent one of the most successful commercial applications of 3D printing in medical devices. The ear canal’s unique shape in each individual creates natural demand for customization. Traditional hearing aid manufacturing used impression materials and manual shell fabrication, requiring skilled labor and substantial time. Modern hearing aid production uses digital ear scans and 3D printing to manufacture custom shells that fit each patient precisely. Major hearing aid manufacturers have adopted this workflow industry-wide, producing millions of 3D printed hearing aid shells annually.

Dental applications span the full spectrum from diagnostic models through treatment planning to finished dental restorations. Orthodontists print study models of patients’ teeth for diagnosis and treatment planning, eliminating the need for physical impressions and stone models. Clear aligner therapy systems like Invisalign use 3D printing to manufacture molds that form the clear aligners, with each patient’s complete treatment series requiring unique molds for dozens of incremental tooth positions. Dental laboratories print surgical guides for implant placement, custom impression trays, temporary crowns, and even some permanent restorations depending on material properties and regulatory clearances.

Bioprinting, where living cells are deposited in patterns to create tissue structures, represents an emerging frontier that remains largely in research stages but shows promise for future medical applications. Researchers have demonstrated printing simple tissues like skin, cartilage, and even organoids with basic organ functions. The technology faces substantial challenges around vascularization to supply printed tissues with nutrients and oxygen, and achieving the complexity of native tissues remains distant. However, even simple printed tissues may find applications in drug testing, disease modeling, or eventually as grafts for wound healing.

Regulatory considerations shape what medical applications can reach clinical use. Medical devices require regulatory clearance or approval demonstrating safety and effectiveness. For patient-specific devices, regulatory frameworks have evolved to allow manufacturers to validate design processes and material properties rather than individually testing each custom device. This enables practical deployment of customized printed devices while maintaining patient safety. However, navigating these regulatory requirements adds complexity compared to non-medical applications and requires substantial expertise and documentation.

Manufacturing Tools, Fixtures, and Aids

One of the most economically compelling applications of three-dimensional printing in manufacturing environments involves producing tools, fixtures, jigs, and work-holding devices used on factory floors. These applications leverage additive manufacturing’s quick turnaround and customization capabilities while avoiding some limitations around mechanical properties or surface finish that might constrain end-use part production.

Custom work-holding fixtures represent perhaps the most common manufacturing aid produced through 3D printing. When setting up machining operations, assembly stations, or quality inspection procedures, workers need fixtures that locate and hold parts in specific orientations. Traditional fixture manufacturing requires machining or fabricating metal fixtures, a process that can take days or weeks and cost hundreds or thousands of dollars. Three-dimensional printing allows designing and producing custom fixtures in hours or days at material costs of perhaps ten to fifty dollars, dramatically reducing both lead time and expense.

The design freedom of additive manufacturing proves particularly valuable for fixture creation because optimal fixture geometry often involves complex shapes that conform to part surfaces, provide multiple clamping points, or integrate features that would require multiple operations to machine. A fixture might need to cradle a complex curved surface while providing openings for tooling access and incorporating quick-release clamps. This geometry prints readily but would be expensive and time-consuming to produce through conventional machining.

Assembly fixtures and jigs guide workers in correctly positioning components during assembly operations. An assembly jig might hold circuit board components in position for soldering, locate parts during adhesive bonding, or ensure proper alignment when inserting fasteners. The ability to rapidly produce these aids allows lean manufacturing approaches where fixtures are created specifically for each product variant or updated quickly when assembly procedures change. The low cost of printed fixtures makes it economically sensible to create specialized aids for operations that might not justify expensive conventional fixturing.

Go/no-go gauges and inspection tools allow quality control checking of dimensional features without requiring expensive precision measurement equipment for every check. A 3D printed gauge might verify that a hole falls within acceptable diameter limits, a feature’s position sits within tolerance, or an assembly has correct overall dimensions. While these printed gauges lack the precision of machined gage blocks, they provide adequate accuracy for many quality checks at dramatically lower cost and lead time. Production workers can use these gauges at their workstations for quick verification rather than sending every part to quality control for formal measurement.

End-of-arm tooling for robots represents another compelling application where 3D printing provides value. When programming robots for assembly, material handling, or packaging operations, engineers need custom grippers, vacuum cups, or tool interfaces that match the specific parts being handled. Traditional tooling requires machining or fabricating these components, adding time and cost to robot deployment. Three-dimensional printing allows creating custom end-effectors in parallel with robot programming, accelerating deployment timelines. The relatively low forces involved in many robotic handling operations mean printed tooling can perform adequately even if it cannot match metal’s strength or durability.

Soft jaws for vises represent parts that manufacturers routinely custom-make for specific workpieces. Standard vise jaws might damage soft materials or fail to grip complex shapes securely. Custom soft jaws machined from aluminum or plastic provide better gripping without marring parts. Three-dimensional printing offers an alternative where soft jaws can be designed to conform to specific part geometries and printed in materials appropriate for the application, whether rigid plastic for mechanical grip or flexible material for delicate parts.

Paint masks and shields protect specific areas during finishing operations. When spray painting, powder coating, or applying surface treatments to products with multiple materials or regions requiring different finishes, masks prevent coating from reaching areas that should remain bare. Complex masking patterns that conform to three-dimensional surfaces can be challenging to create from flat masking tape or sheet materials. Three-dimensional printing produces custom masks that locate precisely on parts and provide defined coating boundaries without time-consuming hand masking.

Shadow boards and tool organizers improve manufacturing efficiency by providing designated locations for tools, reducing time spent searching for items and making missing tools immediately obvious. Custom shadow boards that precisely match specific tool collections can be designed and printed to fit available wall space or storage areas. The low cost of printed organizers makes it practical to create optimized storage for every tool set rather than using generic storage that wastes space or provides poor organization.

The economics of these manufacturing aid applications work favorably because the cost comparison is not against high-volume production but against custom-made alternatives like machined fixtures or fabricated work holders. The printed versions might cost ten percent of equivalent machined fixtures while providing ninety percent of the functionality for many applications. Even if printed fixtures wear out faster than metal equivalents, replacing them costs so little that disposable fixtures become economically sensible when designs change frequently or production volumes are limited.

Aerospace Components and Applications

The aerospace industry has emerged as one of the most enthusiastic adopters of additive manufacturing for production components despite being one of the most demanding industries regarding material properties, quality documentation, and regulatory compliance. This adoption reflects how additive manufacturing’s unique capabilities address specific aerospace challenges around weight reduction, complex geometries, and low production volumes in ways that justify the substantial effort required to qualify new manufacturing processes.

Weight reduction represents the primary driver for aerospace adoption of 3D printing because every kilogram removed from an aircraft translates directly into fuel savings over millions of flight miles. The ability to use topology optimization and lattice structures creates parts that achieve required mechanical properties at fractions of traditional component weights. Brackets, ducting components, and structural elements redesigned for additive manufacturing can show weight savings of thirty to fifty percent while maintaining equivalent strength and stiffness.

The GE LEAP engine fuel nozzle represents one of the most celebrated examples of production additive manufacturing in aerospace. The original design assembled from twenty separate parts that required welding and brazing. Redesigning for additive manufacturing consolidated the assembly into a single printed part that weighs twenty-five percent less and demonstrates five times greater durability than the original design. This single component delivers measurable fuel savings across the engine’s operational lifetime while simplifying supply chain and assembly operations. GE has produced tens of thousands of these nozzles through additive manufacturing, demonstrating the technology’s readiness for high-volume aerospace production.

Complex internal geometries that would be impossible or prohibitively expensive to manufacture through traditional methods become feasible with additive processes. Aerospace components often benefit from internal channels for cooling, lightweighting cavities in precise locations, or integrated mounting features. A hydraulic manifold that traditionally machined from a billet with drilled and plugged passages can be redesigned with organic flow channels optimized for pressure drop and flow distribution, then printed in a single operation. The resulting part can be lighter, perform better, and eliminate the leak points that plugged passages create.

Production volumes in aerospace often fall in ranges where additive manufacturing shows economic advantages over traditional manufacturing. Commercial aircraft may be produced in quantities of hundreds or low thousands over decades-long production runs. Military aircraft, space vehicles, and satellite systems may be produced in dozens or hundreds of units. At these production volumes, the high cost of production tooling for traditional manufacturing becomes difficult to justify, particularly for components that may undergo design iterations. Additive manufacturing’s elimination of tooling costs makes it competitive at these volumes.

The long service lives of aerospace assets create spare parts challenges that additive manufacturing addresses effectively. Aircraft may operate for thirty years or more, requiring replacement parts throughout their service lives. Maintaining inventory for all possible spare parts becomes prohibitively expensive, yet obsolescence of traditional manufacturing tooling means some parts cannot be produced when needed. Three-dimensional printing allows producing spare parts on demand from digital files, eliminating inventory costs while ensuring parts availability throughout the aircraft’s lifetime.

Material qualification represents a substantial barrier to aerospace adoption that the industry has worked systematically to overcome. Aerospace applications require materials with documented and validated properties, consistent production quality, and complete traceability. The industry has invested heavily in qualifying additive processes and materials, conducting extensive mechanical testing, developing process specifications, and establishing quality control procedures. Materials like titanium alloys, nickel superalloys, and aluminum alloys have been qualified for various aerospace applications through this work.

Non-destructive evaluation methods for additively manufactured aerospace parts continue evolving to address inspection challenges. Internal voids or defects that could compromise structural integrity must be detected reliably. X-ray computed tomography provides volumetric inspection of entire parts, revealing internal defects that surface inspection would miss. Process monitoring during manufacture uses sensors to detect anomalies during building, potentially catching defects as they form rather than discovering them only after completion. These inspection technologies add cost and complexity but enable the quality assurance that aerospace applications demand.

Rocket engine components represent another area where additive manufacturing shows compelling advantages. Rocket engines require complex cooling channels to prevent thermal failure, extensive manifolding to distribute propellants, and precise geometric control over combustion chamber shapes. Companies like SpaceX and Rocket Lab have developed rocket engines with additively manufactured combustion chambers and injectors that demonstrate performance advantages over traditional designs while reducing part counts and manufacturing time. The small production volumes and extreme performance requirements of rocket engines align well with additive manufacturing’s capabilities.

Automotive Industry Applications

The automotive industry’s relationship with three-dimensional printing has evolved from purely prototyping applications toward increasing use for production tooling, customization, and even end-use parts in specific contexts. The industry’s enormous production volumes, extreme cost sensitivity, and highly developed traditional manufacturing infrastructure mean that additive manufacturing must demonstrate clear advantages to displace established processes for mainstream components.

Prototype development represents the most mature automotive application of 3D printing, with virtually every automotive manufacturer and supplier using the technology to accelerate design validation. The ability to produce prototype parts overnight allows rapid iteration through design alternatives for everything from exterior styling elements to interior trim components to under-hood mechanical parts. Design studios print clay-model alternative proposals in hard materials that can be painted and evaluated alongside traditional clay models. Engineering teams print functional prototypes to test fit, assembly, and basic mechanical function before committing to costly tooling.

Customization and personalization applications leverage additive manufacturing’s ability to economically produce unique variants. Luxury and performance vehicle manufacturers offer custom interior trim elements, badging, and accessories that would be economically impractical to produce through traditional methods for individual customers. The relatively high vehicle prices and low production volumes of these segments can absorb the higher unit costs of additive manufacturing while providing differentiation through customization that mass-market manufacturers cannot match.

Production tooling, fixtures, and assembly aids represent substantial automotive applications where many manufacturers have deployed 3D printing successfully. The same benefits seen in general manufacturing apply: rapid production of custom fixtures, assembly jigs, and quality control gauges at low cost compared to machined alternatives. Automotive manufacturers have reportedly produced tens of thousands of printed tools and fixtures used in assembly plants, demonstrating that the technology can withstand the rigors of production environments while providing economic and time-to-deployment advantages.

Replacement parts for classic and collectible vehicles represent a niche but growing application. Original tooling for vehicles that ceased production decades ago may no longer exist, making replacement parts unavailable or extremely expensive when sourced from remaining inventory. Three-dimensional scanning and reverse engineering allows recreating parts from surviving examples, then printing replacements as needed. Enthusiasts and restoration shops can obtain interior trim pieces, exterior badges, mechanical components, and other parts that would otherwise be unavailable or require costly custom fabrication.

Low-volume production vehicles like supercars, racing vehicles, and specialty conversions increasingly use 3D printed components in production. A supercar manufacturer producing dozens rather than thousands of vehicles annually cannot justify the tooling investment for traditional manufacturing of every component. Parts that do not face extreme mechanical or thermal loads, such as interior trim, ductwork, brackets, and mounting components, may be 3D printed in production quantities. This allows achieving the desired design without the economic burden of tooling that would add substantially to the vehicle’s cost.

Motorsports applications push additive manufacturing’s capabilities for functional parts operating under demanding conditions. Racing teams need custom parts in very small quantities with short development timelines. The ability to design, print, test, and iterate on components between race events provides competitive advantages. Aerodynamic elements, suspension components, cooling system parts, and interior elements can be optimized for specific tracks or conditions, then printed in time for race weekends. The willingness of motorsports to accept higher costs for performance advantages creates a favorable economic environment for additive manufacturing.

Electric vehicle manufacturers, particularly newer companies without legacy manufacturing infrastructure, show greater willingness to incorporate additive manufacturing into production than traditional automotive manufacturers. The smaller production volumes during initial scaling, the need for rapid iteration as designs evolve, and the lack of established supplier relationships make additive manufacturing relatively more attractive. Some electric vehicle startups have integrated structural lattice components, custom battery pack elements, and optimized brackets into production designs that leverage additive manufacturing’s capabilities.

Education and Research Applications

Educational institutions from elementary schools through universities have embraced three-dimensional printing as a tool for hands-on learning, design education, and research across diverse disciplines. The technology’s ability to transform digital designs into physical objects provides unique learning opportunities that engage students in ways that passive observation or screen-based activities cannot match.

STEM education benefits significantly from the tangible nature of 3D printed objects. Students learning mathematical concepts can print geometric solids to visualize properties of shapes, volumes, and surface areas. Physics students can design and print mechanisms to explore mechanical advantage, gear ratios, or structural principles. Chemistry students can examine 3D printed molecular structures that show spatial relationships between atoms more clearly than two-dimensional diagrams. Biology students can study anatomical models that show internal organs and their spatial relationships. The ability to hold and manipulate these objects enhances understanding in ways that pictures or videos cannot replicate.

Design and engineering education increasingly incorporates 3D printing as students learn computer-aided design and product development processes. Rather than completing design projects that remain digital, students can print their designs and evaluate them physically. This immediate feedback helps students understand how design decisions affect manufacturability, functionality, and aesthetics. Iterating through multiple design versions within a semester or even a single project gives students experience with the design-build-test cycle that professional engineers use routinely.

Art and design programs use 3D printing as a creative medium that expands possibilities beyond traditional sculpture and fabrication techniques. Students explore generative design algorithms that create complex organic forms, experiment with geometric patterns and mathematical relationships visualized in three dimensions, and combine digital fabrication with traditional art-making techniques. The geometric freedom of additive manufacturing allows creating forms that would be difficult or impossible through traditional sculpture methods, expanding creative possibilities.

Research applications span numerous fields where 3D printing enables work that would otherwise be impractical or impossible. Archaeologists and paleontologists print replicas of fragile artifacts and fossils, allowing hands-on study without risking damage to irreplaceable originals. The replicas can be shared with researchers globally, distributed to multiple institutions, or used in educational displays while originals remain protected. Anthropologists studying ergonomics and tool use can print replicas of historical tools for experimental archaeology research.

Biological research uses 3D printing for microfluidic devices that manipulate tiny fluid volumes for cell culture, drug screening, and diagnostic testing. These devices contain complex channel networks that would be expensive to produce through traditional microfabrication techniques. Three-dimensional printing allows researchers to rapidly prototype and iterate on designs, accelerating research progress. Some biological research uses 3D printed scaffolds for tissue engineering research, with the scaffold geometry controlling how cells grow and organize.

Robotics research leverages 3D printing extensively for rapidly prototyping robot bodies, grippers, mechanisms, and custom components. The ability to quickly manufacture one-off parts allows researchers to test design concepts without waiting for traditional manufacturing. Many research robots incorporate substantial percentages of 3D printed components, from structural elements to housings for electronics to custom linkages and joints. The design freedom enables creating optimized structures that would be difficult to machine or fabricate conventionally.

Library makerspaces and school fabrication labs have democratized access to 3D printing technology, allowing students without personal printers to gain hands-on experience. These shared resources provide supervised access to equipment, support for learning the technology, and community around making and fabrication. Students can work on personal projects, complete class assignments, participate in competitions, or simply explore the technology’s possibilities. The presence of 3D printers in educational institutions has exposed millions of students to additive manufacturing concepts that previous generations never encountered.

Project-based learning activities built around 3D printing engage students in solving real problems through design thinking and iterative development. Students might design adaptive equipment for individuals with disabilities, create solutions to local environmental challenges, develop games or toys with specific educational purposes, or tackle engineering challenges like building bridges or protective structures. The tangible output from these projects and the ability to physically test and refine designs creates engagement that purely theoretical exercises often lack.

Consumer Products and Household Items

Consumer applications of three-dimensional printing span from individuals printing useful items at home through small businesses producing custom products through contract manufacturers offering mass customization services. This spectrum demonstrates how additive manufacturing enables new business models and product categories while also empowering consumers to become producers rather than purely purchasers of manufactured goods.

Replacement parts represent one of the most practical home applications of 3D printing. When plastic components on appliances, gadgets, or household items break, replacement parts may be unavailable, expensive, or require waiting for shipping. If the broken part is plastic and not subject to extreme mechanical or thermal loads, printing a replacement part becomes feasible. Online repositories contain thousands of replacement part models for common items, from vacuum cleaner parts to dishwasher racks, from toilet seats to appliance knobs. The ability to fix rather than discard items extends their useful lives and provides economic value that can justify the cost of owning a 3D printer.

Organization and storage solutions print on demand to fit specific spaces and requirements. Custom drawer dividers sized exactly for particular drawers, pegboard accessories designed for specific tools, cable management solutions that fit precise locations, and modular storage systems that expand as needs change all benefit from the customization that 3D printing enables. Rather than buying generic organization products that never quite fit perfectly, users can design and print solutions optimized for their exact requirements.

Hobby and craft applications span enormous variety as makers print parts for their diverse interests. Photography enthusiasts print custom camera accessories, lens hoods, and mounting brackets. Radio-controlled vehicle hobbyists print custom parts, upgrade components, and repair pieces for models. Tabletop gaming enthusiasts print miniatures, terrain, dice towers, and game accessories. Knitters and sewers print custom tools, thread guides, and project accessories. The ability to find or design specialized tools and accessories for niche hobbies creates value that mass-manufactured products targeted at broader markets cannot provide.

Custom gifts and personalization opportunities make 3D printing attractive for creating unique items. Printing someone’s name integrated into objects, creating custom ornaments commemorating special dates or events, designing unique jewelry with personal significance, or producing small quantities of custom party favors all leverage the technology’s customization capabilities. The relatively low material costs make these personalized items economically sensible compared to minimum order quantities from traditional manufacturers.

Home decor and functional art represent creative applications where individuals combine aesthetic and practical considerations. Planters designed to fit specific locations and plant sizes, lampshades with custom geometric patterns, wall art with intricate detail, functional sculptures that also serve as bookends or door stops all demonstrate how 3D printing enables creative expression combined with utility. The geometric freedom allows creating forms that would be difficult to produce through traditional craft techniques.

Custom solutions for specific needs represent perhaps the most empowering aspect of consumer 3D printing. When someone has a specific problem that no commercial product addresses, they can design and print a solution. Adapters that connect incompatible components, mounting brackets for unusual installations, specialized tools for particular tasks, or assistive devices that accommodate individual requirements all become possible when individuals can become designers and manufacturers. This democratization of production, while serving relatively niche applications, provides genuine value to individuals who would otherwise lack solutions.

Small-scale entrepreneurship enabled by 3D printing allows individuals to design products and sell them through online marketplaces like Etsy without substantial capital investment. Cookie cutters in custom shapes, plant markers with personalized labels, custom phone cases, unique jewelry designs, and countless other niche products demonstrate how additive manufacturing enables microbusinesses. The lack of minimum order quantities or tooling investments means entrepreneurs can test market reception with minimal financial risk.

Conclusion

The question “What can you actually make with a 3D printer?” reveals upon examination not a simple list but rather a complex landscape of applications spanning from individual hobbyists printing household items through researchers creating experimental devices to aerospace manufacturers producing flight-certified components. The breadth of this application spectrum demonstrates that three-dimensional printing has transcended its origins as a prototyping tool to become a genuinely versatile manufacturing technology.

The applications that make the most sense for additive manufacturing share common characteristics that align with the technology’s fundamental strengths. Low production volumes where tooling costs cannot be amortized, complex geometries that leverage design freedom, customization requirements where each unit differs, rapid iteration needs during development, weight reduction opportunities through topology optimization, and on-demand production of parts with sporadic demand all favor 3D printing over traditional manufacturing methods.

Understanding this application landscape helps set realistic expectations about what 3D printing can accomplish today versus future possibilities that remain under development. The technology excels at producing prototypes, custom medical devices, manufacturing aids, low-volume production parts, replacement components, educational models, and personalized consumer items. It struggles with high-volume standardized production, parts requiring extreme precision or surface finish, and applications demanding material properties that available additive materials cannot provide.

As the technology continues maturing with expanding material options, improving process capabilities, declining equipment costs, and growing design expertise, the range of practical applications will broaden. However, the fundamental principles that determine when additive manufacturing provides value will remain relevant. Whether you are considering purchasing a printer for home use, evaluating the technology for business applications, or simply trying to understand the practical impact of 3D printing, recognizing these principles allows informed decisions about when and how to leverage this transformative technology.

The real answer to “What can you make with a 3D printer?” is not a catalog of objects but rather an understanding of the types of problems and requirements that additive manufacturing addresses particularly well, combined with recognition of where traditional methods retain decisive advantages. This nuanced understanding empowers better manufacturing decisions than simply assuming 3D printing is either universally applicable or limited to novelty items. The technology has earned its place as a genuine manufacturing method while remaining one option among many rather than a replacement for all traditional processes.