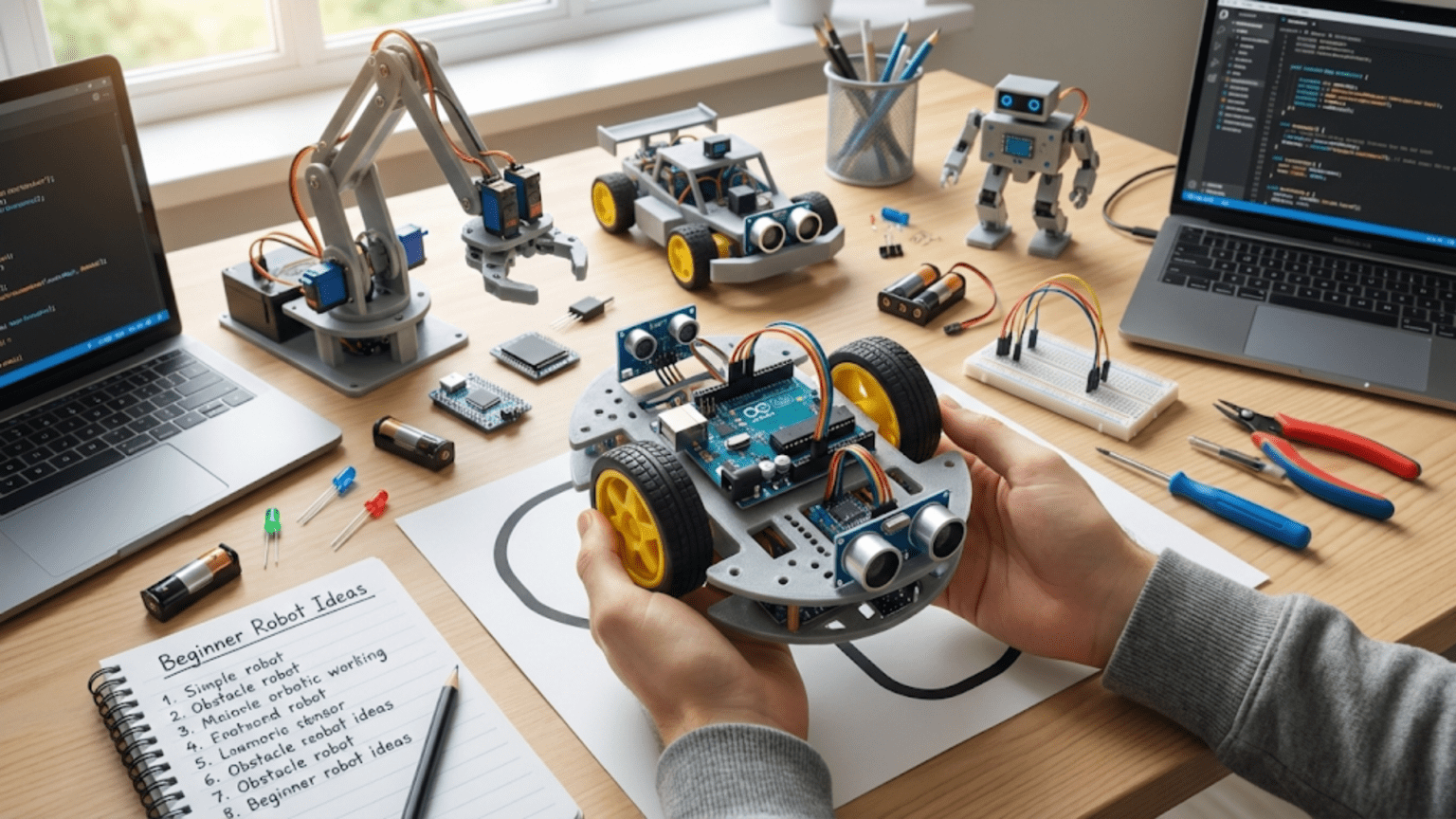

When you first become interested in robotics, your imagination likely fills with visions of sophisticated machines performing complex tasks. You watch videos of robots doing backflips, autonomous vehicles navigating city streets, or robotic arms assembling intricate products with precision. These impressive demonstrations can make you wonder what you could realistically achieve as someone just starting out. Understanding what beginner roboticists can actually build helps set appropriate expectations, prevents discouragement, and reveals the surprising range of meaningful projects accessible even to complete newcomers.

The gap between beginner capabilities and expert demonstrations is smaller than you might think. While you will not build a humanoid robot that performs gymnastics in your first month, you can absolutely create functional robots that navigate autonomously, respond to their environment, and accomplish real tasks. Many beginner projects teach fundamental concepts that directly scale to advanced applications. The obstacle-avoiding robot you build as your second project uses the same basic principles of sensing and reactive control that guide million-dollar autonomous vehicles, just implemented more simply.

This article explores the spectrum of projects accessible to beginners, organized by complexity and the skills they teach. Understanding this landscape helps you choose appropriate starting projects that match your current abilities while building toward more ambitious goals. Each project category demonstrates specific robotics principles, and completing projects across these categories gradually develops the broad skill set that robotics requires.

Your Very First Robot: The Absolute Basics

Your first robotics project should accomplish something visible and satisfying while remaining simple enough to complete successfully. Nothing builds confidence like finishing a project that actually works, even if that project seems elementary to experienced builders. The goal at this stage involves learning fundamental workflows including how to connect components, upload code to a microcontroller, power your creation, and troubleshoot basic problems.

A light-following robot represents an excellent first project for many beginners. This robot uses light sensors to detect bright areas and moves toward them, creating behavior that appears almost alive despite remarkably simple underlying mechanisms. You need only a basic wheeled platform, two motors, light sensors, and straightforward control logic. When the left sensor detects more light, the robot turns left. When the right sensor sees more light, it turns right. This direct sensory-motor coupling produces engaging behavior from minimal code.

The classic blinking LED circuit, while not a robot by strict definition, teaches crucial basics about microcontroller programming, electronic connections, and the immediate feedback loop between code and physical action. Watching an LED blink according to your program provides visceral confirmation that your code controls real-world hardware. This fundamental experience prepares you for controlling motors, reading sensors, and building actual robots.

A simple bumper robot that drives forward until hitting something, then backs up and turns, demonstrates the core robotics loop of sensing, deciding, and acting. Mechanical bumper switches or touch sensors detect collisions, your code makes decisions about how to respond, and motors execute the reversing and turning actions. Despite its simplicity, this project introduces you to sensor input handling, conditional logic, and motor control, which form the foundation of more complex behaviors.

Building a basic wheeled platform that you can drive via remote control teaches mechanical assembly, motor wiring, and wireless communication without requiring autonomous decision-making code. Using a Bluetooth module or infrared remote, you send commands that your robot receives and executes. This project helps you understand motor direction control, speed variation through pulse width modulation, and the satisfaction of commanding a robot you built yourself.

Line Following and Path Navigation

Line-following robots represent the next step up in complexity and introduce crucial concepts about navigation and control systems. These robots use sensors to detect a line on the floor, typically black tape on a white surface or vice versa, and follow it autonomously. The challenge involves keeping the robot centered on the line as it curves and turns, which requires continuous sensing and motor adjustment.

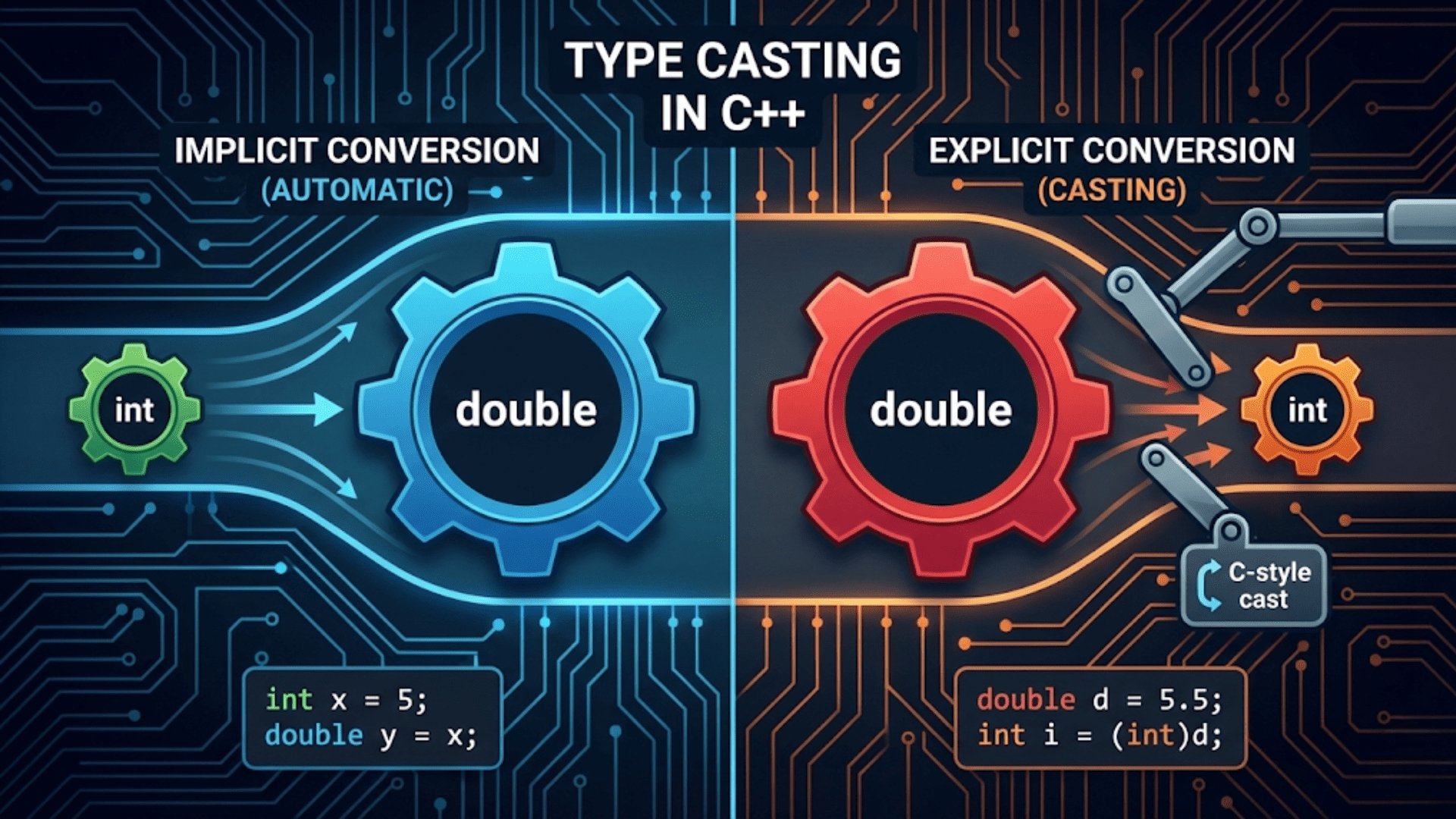

A basic line follower using two or three sensors demonstrates binary decision-making. If the left sensor detects the line, turn right to recenter. If the right sensor detects the line, turn left. This bang-bang control approach works but produces jerky, zigzagging motion as the robot constantly overcorrects. Building this version first helps you understand why more sophisticated control approaches exist.

Improving your line follower with proportional control creates dramatically smoother navigation. Instead of full-speed turns when you detect error, you adjust motor speeds proportionally to how far off-center the robot has strayed. Small deviations cause small corrections, while larger errors trigger stronger adjustments. This introduction to proportional control provides your first taste of control theory, which becomes increasingly important as projects grow more complex.

Adding integration and derivative terms to create a full PID controller takes your line follower from functional to impressively smooth. The integral term helps eliminate steady-state errors where the robot consistently runs slightly off-center, while the derivative term anticipates future error based on how quickly the error is changing. Tuning a PID controller teaches you patience and systematic experimentation as you adjust parameters to optimize performance.

Line maze solving extends line following by adding decision points where the robot must choose paths. You can program strategies like always turning right at intersections, which guarantees finding the exit of certain maze types, or more sophisticated approaches that map the maze and calculate optimal paths. These projects introduce algorithmic thinking and memory-based navigation.

Obstacle Detection and Avoidance

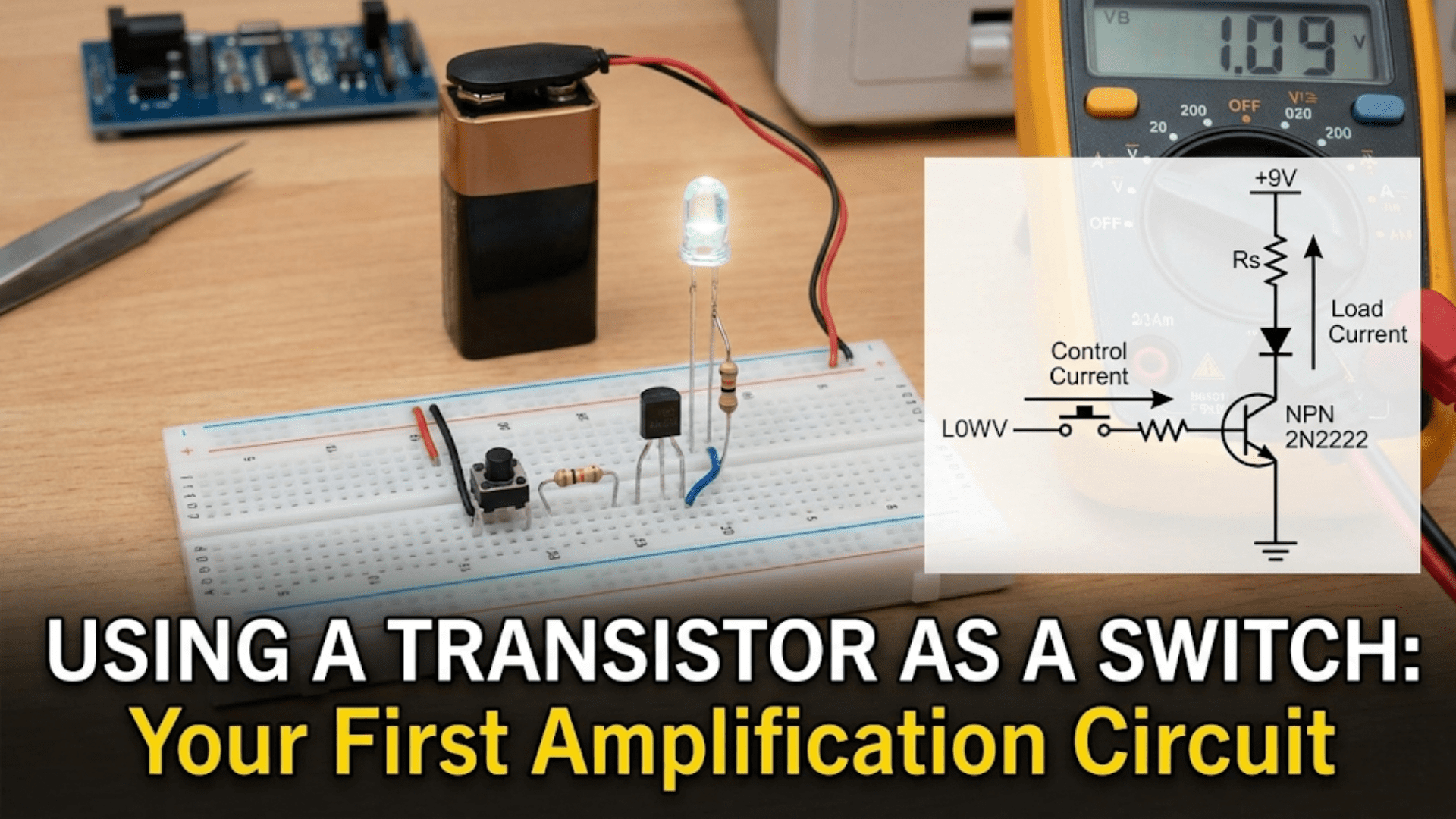

Obstacle-avoiding robots teach you about different sensor types and how robots perceive their environment. Unlike line followers that look down at predictable markings, obstacle avoiders must detect and respond to three-dimensional objects in their path. This challenge introduces range-finding sensors and more complex decision-making algorithms.

An ultrasonic sensor-based avoider provides excellent introduction to distance measurement. Ultrasonic sensors emit sound pulses and measure how long echoes take to return, calculating distance from timing. Your robot can detect objects ahead and decide whether to stop, turn, or back up based on measured distances. This project teaches analog sensor reading, distance calculation, and threshold-based decisions.

Infrared proximity sensors offer an alternative approach with faster response but shorter range. Building a robot with multiple infrared sensors around its perimeter creates a system that detects obstacles from multiple directions simultaneously. You learn about sensor arrays and how to integrate multiple inputs into cohesive behavior.

Combining multiple sensor types demonstrates sensor fusion principles. Your robot might use long-range ultrasonic sensors to detect distant obstacles while infrared sensors catch nearby objects the ultrasonic beam missed. Learning to combine different sensory information mirrors how advanced robots and autonomous vehicles use multiple sensor technologies together.

Creating wall-following behavior represents a specific application of obstacle avoidance where your robot maintains constant distance from a wall while moving forward. This project introduces feedback control with a clear, measurable goal: keeping the wall sensor reading at a specific distance value. You can implement this with simple proportional control or experiment with full PID control for smooth, consistent wall-following.

Robotic Arms and Manipulation

Moving from mobile robots to stationary manipulators introduces entirely new challenges around precision positioning, coordinate systems, and inverse kinematics. Even simple robotic arms teach valuable lessons about how robots interact with objects rather than just moving through space.

A two-joint arm controlled by servo motors provides your introduction to articulated manipulation. You can directly control each servo angle, moving the arm through a range of positions. This direct control, called forward kinematics, helps you understand how joint angles determine end effector position. Adding a simple gripper lets your arm pick up light objects, creating surprisingly satisfying interaction.

Programming your arm to reach specific coordinates requires inverse kinematics, where you calculate necessary joint angles to place the end effector at desired positions. For two-joint planar arms, the mathematics remains accessible to beginners willing to work through some trigonometry. Successfully implementing inverse kinematics feels like genuine robotics engineering because you are solving the same types of problems that industrial robot programmers handle.

A drawing robot that holds a pen creates visible output from your arm’s movements. Programming it to draw shapes, write letters, or reproduce simple images teaches path planning and motion control. The immediate visual feedback helps you understand how positioning errors accumulate and why precision matters in manipulation tasks.

Adding sensors to your robotic arm enables it to respond to its environment. Force sensors can detect when the gripper successfully grasps an object or encounters excessive resistance. Limit switches indicate when joints reach their travel limits. These sensory additions transform your arm from a purely commanded system into one that adapts based on what it feels.

Balancing and Dynamic Robots

Self-balancing robots introduce dynamic control challenges completely different from static robots. Unlike wheeled rovers that remain stable on their own, balancing robots constantly fall unless actively corrected. This challenge teaches real-time control, sensor fusion, and the satisfying difficulty of keeping unstable systems stable.

A two-wheeled balancing robot similar to a Segway provides an accessible introduction to balancing. Using an inertial measurement unit that combines accelerometer and gyroscope, your robot detects its tilt angle and moves its wheels to keep the tilt centered. This project requires faster control loops than previous projects, teaching you about real-time performance requirements.

Implementing complementary or Kalman filters to clean sensor data becomes necessary for smooth balancing. Raw accelerometer and gyroscope readings contain noise and drift that cause erratic behavior if used directly. Learning to fuse these sensors into clean angle estimates teaches sophisticated signal processing while remaining understandable at a conceptual level.

Tuning the PID controller for a balancing robot provides visceral feedback about control parameters. Too much proportional gain causes violent oscillation. Too little leaves the robot too slow to catch falls. The derivative term that seemed abstract in line-following becomes obviously necessary when you see how it dampens oscillations and stabilizes behavior.

Once your robot balances reliably, you can add controlled movement by intentionally tilting forward or backward. Steering while balancing introduces additional control complexity as you coordinate tilt angle control with differential wheel speeds for turning. These challenges prepare you for understanding how more complex dynamic robots coordinate multiple control objectives simultaneously.

Environmental Interaction and Measurement

Robots that measure and report environmental conditions introduce you to data collection, calibration, and practical applications beyond just moving around. These projects often prove directly useful while teaching important robotics principles.

A weather station robot that measures temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, and light levels teaches sensor integration and data logging. Reading multiple sensors, converting raw values to meaningful units, and recording or transmitting this data creates a complete sensing system. Adding mobility lets your robot collect measurements from multiple locations automatically.

Soil moisture monitoring robots serve practical purposes for gardens or agriculture while teaching analog sensor reading and threshold-based decisions. Your robot can water plants automatically when moisture drops below set points, combining sensing with actuated response to close the control loop.

Sound level monitoring robots introduce acoustic sensing. Microphone sensors detect sound intensity, letting your robot map noise levels across an area or respond to specific sounds. This project teaches analog signal processing and threshold detection for event-triggered behaviors.

Air quality monitoring becomes increasingly relevant as environmental awareness grows. Gas sensors detecting carbon dioxide, volatile organic compounds, or specific gases let your robot assess air quality. Combining multiple gas sensors with particulate matter sensors creates comprehensive environmental monitoring platforms.

Swarm Behaviors and Multi-Robot Systems

Once you have built several individual robots, creating systems where multiple robots interact introduces entirely new challenges around communication, coordination, and emergent behavior. Even simple multi-robot projects teach valuable lessons about distributed systems.

Two robots following each other using infrared or optical sensors demonstrates leader-follower behavior with minimal communication. The follower simply maintains constant distance from the leader using distance sensors, creating basic formation control. This project teaches you about relative positioning and reactive following behaviors.

Coordinated movement patterns with three or more robots create visual displays while teaching broadcast communication. All robots receive the same movement commands via wireless communication, executing synchronized movements. Adding timing delays or position-dependent variations creates interesting collective behaviors from simple individual rules.

Cooperative object pushing where robots work together to move objects too heavy for one robot alone introduces task-level coordination. Robots must position themselves appropriately and push in coordinated directions. This project teaches distributed problem-solving without centralized control.

Simple swarm behaviors emerge when individual robots follow basic rules that produce collective organization. Robots that avoid each other while moving toward a target naturally spread out to explore areas. Adding attraction rules at longer ranges and repulsion at close range produces flocking behavior similar to birds or fish.

Interactive and Responsive Robots

Projects where robots interact with humans introduce considerations beyond pure functionality including user experience, safety, and communication design. These robots respond to human input or presence in engaging ways.

A gesture-controlled robot using distance sensors or accelerometers lets you command it through hand movements. Swiping your hand in different directions sends corresponding movement commands. This project teaches gesture recognition through sensor pattern matching and wireless control.

Light-painting robots that you guide through space while a long-exposure camera captures their movement create artistic output. Adding color-changing LEDs controlled by buttons or sensors lets you paint with light in three dimensions. This project combines robotics with visual art in engaging ways.

Sound-reactive robots that respond to claps, music, or voice commands introduce audio processing. Simple implementations detect sound volume and trigger behaviors when thresholds are exceeded. More sophisticated versions can distinguish different sounds or respond to specific frequencies.

Following robots that track and maintain distance from a person create engaging interaction. Using sensors to detect the person and motor control to maintain appropriate following distance, these robots demonstrate autonomous tracking behavior. Adding obstacle avoidance prevents collisions when following through cluttered spaces.

Educational and Demonstration Robots

Some projects serve primarily to teach or demonstrate specific concepts rather than accomplish practical tasks. These pedagogical robots help you understand principles that apply broadly across robotics.

Gait generation demonstrations with hexapod or quadruped robots teach about walking gaits, gait transitions, and body stabilization during locomotion. Even simple implementations where you manually program different gait patterns help you understand the complexity of legged locomotion.

Forward and inverse kinematics demonstrators using multi-joint arms with visual display help you understand the mathematics of robot positioning. Seeing how different joint angle combinations produce end effector positions, and how positions map back to joint angles, makes abstract mathematical concepts concrete.

Sensor comparison robots that simultaneously use different sensor types to solve the same problem teach about sensor characteristics. Building a robot that avoids obstacles using ultrasonic, infrared, and bump sensors separately lets you directly compare their performance, range, response time, and failure modes.

Control algorithm comparison platforms let you implement different control approaches on identical hardware. Comparing bang-bang, proportional, PI, and PID control for the same task demonstrates why more sophisticated control matters and helps you develop intuition about controller behavior.

Setting Realistic Expectations and Goals

Understanding what you can build as a beginner helps you set achievable goals while maintaining ambitious vision. Your first robots will be simple compared to professional systems, but each teaches essential concepts that scale to advanced applications. The line follower you build this month uses the same sensor-feedback-motor control structure that autonomous vehicles use, just with simpler sensors and algorithms.

Progress in robotics happens through incremental improvement rather than sudden breakthroughs. Your first obstacle avoider might jerkily lurch away from walls. Your second version might smoothly navigate using proportional control. Your third might elegantly map the environment and plan optimal paths. Each iteration builds on lessons from previous projects, gradually developing your capabilities.

Choosing projects slightly beyond your current comfort zone accelerates learning while maintaining achievable goals. If a project seems completely incomprehensible, it probably requires intermediate steps first. If it seems trivially easy, you might not learn much. Projects that challenge you but include enough familiar elements to give you starting points provide optimal learning opportunities.

The robots you build as a beginner have value beyond just learning exercises. They work as genuine robots that accomplish real tasks, demonstrate principles, or simply provide satisfaction through their operation. Your line follower might not be commercially viable, but it genuinely navigates autonomously using sensors and control algorithms. That achievement matters regardless of the project’s simplicity.

Looking at your first projects years later after building advanced systems will reveal how much you have learned, but it will also show how those early projects contained seeds of everything you know now. The obstacle avoider taught you about sensing. The line follower introduced control theory. The robotic arm demonstrated manipulation. The balancing robot showed dynamic control. Every beginner project contributes essential understanding to your growing robotics expertise.

As a beginner roboticist, you can build functional mobile robots that navigate autonomously, manipulator arms that reach and grasp, balancing platforms that maintain stability, environmental sensors that collect meaningful data, and interactive systems that respond to human input. These projects teach the fundamental concepts of sensing, control, actuation, and integration that define robotics. Starting simple and building progressively more complex projects will take you from complete novice to capable roboticist faster than you might expect. Your journey begins not with some distant advanced robot but with your next simple project that teaches you something new.