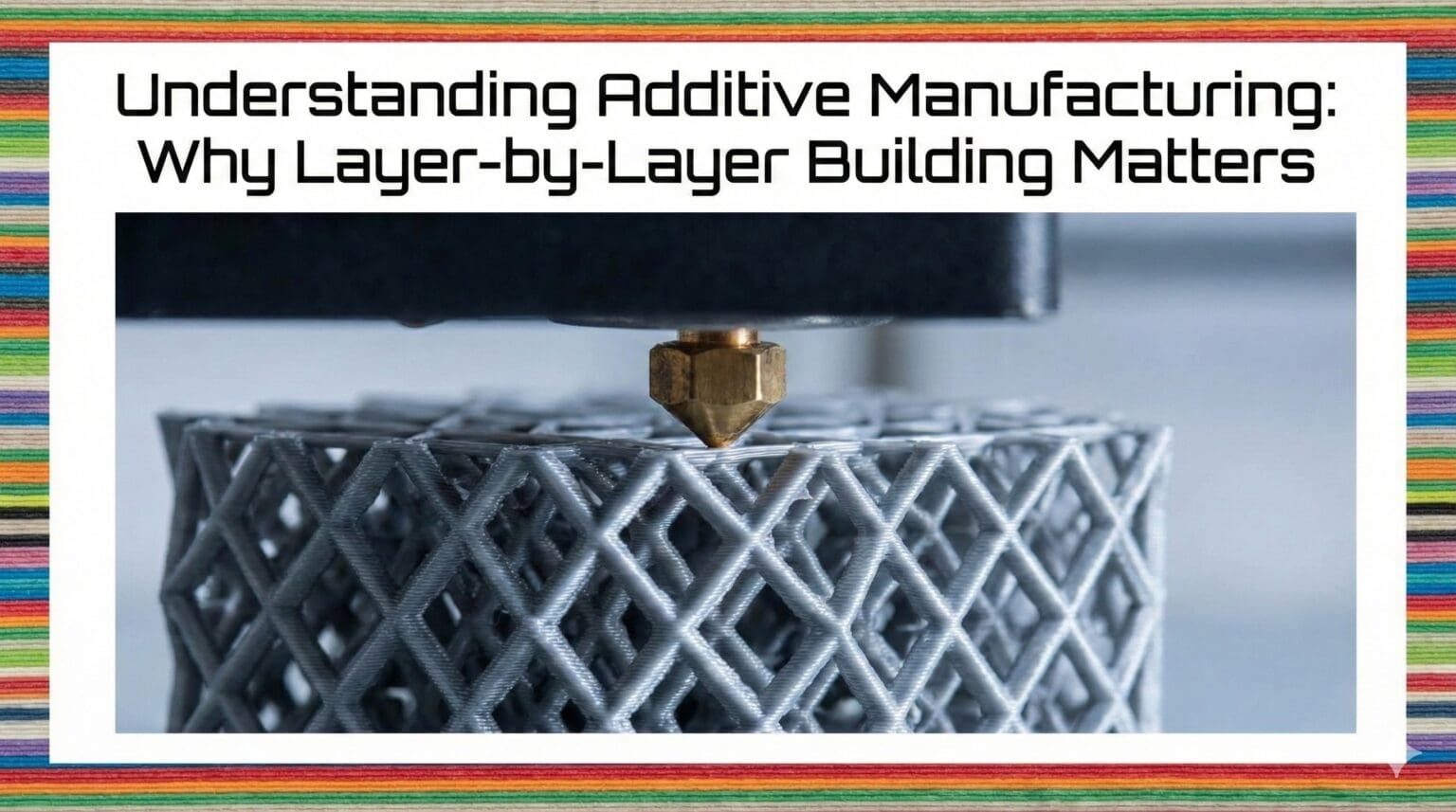

Introduction

The term “additive manufacturing” appears frequently in discussions about modern production technology, often used interchangeably with “3D printing” as if the two concepts are merely different names for the same thing. While this equation holds some truth, the phrase “additive manufacturing” emphasizes a particular aspect of the technology that fundamentally distinguishes it from conventional production methods and explains why this approach creates such transformative possibilities across industries from aerospace to medicine.

The word “additive” refers to how these technologies build objects by adding material incrementally rather than removing it from larger blocks or forming it through molds and dies. This seemingly simple distinction in how material gets arranged during fabrication carries profound implications that ripple through every aspect of the manufacturing process, from initial design concepts through production planning, material consumption, quality control, and end-of-life considerations.

Understanding why the layer-by-layer additive approach matters requires looking beyond the surface observation that objects grow gradually from nothing. The fundamental principle of building up rather than cutting away or forming enables capabilities that were previously impossible, eliminates constraints that shaped design thinking for generations, changes the economic calculus of small-batch production, and creates opportunities for customization that traditional manufacturing cannot match economically.

This comprehensive exploration examines why the additive principle represents more than just a different way to make things. We will investigate how building objects layer by layer changes what geometries become feasible, how it affects material efficiency and waste generation, why it alters the relationship between design complexity and manufacturing cost, how it enables distributed production and supply chain transformation, and what implications it holds for sustainability and resource utilization. By understanding these fundamental principles, you will grasp why additive manufacturing represents a genuine paradigm shift rather than simply an incremental improvement to existing production methods.

The Fundamental Principle of Material Addition

At the heart of additive manufacturing lies a deceptively simple concept: instead of starting with excess material and removing what you do not need, you begin with nothing and add material only where the final object requires it. This inversion of the traditional manufacturing paradigm creates a cascade of consequences that differentiate additive processes from virtually all conventional production methods humanity has developed over millennia.

Traditional manufacturing predominantly relies on subtractive processes where fabrication starts with more raw material than the finished part contains. A machinist begins with a block of metal or plastic and systematically removes material through cutting, drilling, milling, or turning until the desired shape emerges from within the original stock. The removed material becomes waste in the form of chips, turnings, swarf, and dust that must be collected, disposed of, or recycled. For complex parts, the volume of removed material can exceed the volume of the finished part many times over, with removal rates of seventy or eighty percent being common for intricate geometries.

Forming processes like forging, stamping, or bending reshape material without removing it, but these methods still typically start with more material than necessary to ensure complete filling of dies or to provide handling tabs that get trimmed away. Molding processes like injection molding or casting come closer to net-shape manufacturing by filling cavities that closely match the final part geometry, but even these processes generate waste through sprues, runners, gates, and flash that must be removed and either discarded or reprocessed.

Additive manufacturing eliminates this material removal paradigm entirely. The process begins with an empty build volume and deposits material only in locations where the digital model indicates it belongs. A nozzle extrudes plastic only along paths that trace the object’s cross-sections. A laser fuses powder only in regions that become solid parts. A projector cures resin only in areas that should solidify. The surrounding space remains empty, requiring no material and generating no waste from removal operations.

This fundamental difference manifests most obviously in material efficiency. While not perfect, with some waste generated from support structures, failed prints, or unused powder degradation, additive processes typically consume much less raw material per finished part than subtractive alternatives. For expensive materials like titanium alloys or specialty polymers, this efficiency translates directly into cost savings. For environmental considerations, reduced material consumption means lower resource extraction, processing energy, and waste generation throughout the supply chain.

The layer-by-layer implementation of the additive principle introduces another crucial characteristic. Rather than viewing an object as a complete three-dimensional form that must be created in its entirety simultaneously, additive manufacturing decomposes objects into sequences of thin two-dimensional cross-sections that build progressively. Each layer is simple, typically just a pattern of material deposition or solidification across a plane. The complexity arises from stacking hundreds or thousands of these simple layers in precise registration to create the final three-dimensional geometry.

This decomposition into layers provides the key to how additive manufacturing achieves its geometric freedom. Traditional manufacturing must consider how tools access surfaces, how molds open and close, how dies press material, and how forces distribute during forming. These considerations impose geometric constraints that limit what shapes are practical to manufacture. Additive manufacturing sidesteps most of these constraints because each layer only requires depositing material in a two-dimensional pattern, and the previous layer provides support for the next layer regardless of how complex the three-dimensional geometry becomes.

The temporal aspect of layer-by-layer construction also matters. Traditional machining might remove material from multiple locations simultaneously as various cutting edges engage the workpiece. Molding fills the entire cavity at once when injected plastic or molten metal flows through the runners. Additive manufacturing inherently serializes the building process, creating one layer at a time in sequence from bottom to top. This sequential construction means build time correlates primarily with part height and volume rather than geometric complexity, creating different economic trade-offs than traditional methods where complexity often directly increases manufacturing time and cost.

How Layer-by-Layer Construction Enables Design Freedom

The geometric freedom that additive manufacturing provides represents perhaps its most celebrated advantage, and understanding how layer-by-layer construction enables this freedom reveals why certain features that are impossible or prohibitively expensive to manufacture conventionally become trivial with additive approaches.

Consider the challenge of creating an internal cavity within a solid object, with no external opening connecting that cavity to the outside surface. Traditional manufacturing methods struggle with this apparently simple requirement. Machining cannot remove material from inside a solid block without drilling access holes. Casting could create the void if the mold incorporates a core, but extracting that core after the material solidifies requires openings. Even if you could somehow position a core that dissolves after casting, getting the molten material around the core presents flow challenges.

Additive manufacturing handles this geometry effortlessly. As each layer builds, material deposits only where the cross-section indicates solid regions, leaving empty space where the cavity passes through that layer. The cavity exists simply as an absence of material within the surrounding solid structure. No special tools, no complex mold mechanisms, no difficult extractions. The layer-by-layer approach naturally accommodates voids, channels, and complex internal geometries that would confound traditional manufacturing.

Overhanging features provide another example where layer-by-layer construction changes what becomes feasible. Traditional machining finds overhangs difficult because cutting tools must reach underneath the overhang, potentially requiring the part to be repositioned or held differently. Molding requires draft angles on vertical surfaces to allow mold separation, limiting how far features can project outward. Additive manufacturing builds overhangs by depositing material that extends slightly beyond the previous layer, with each layer reaching incrementally farther until the desired overhang angle is achieved.

The concept of support structures emerges naturally from understanding layer-by-layer construction. When a new layer needs to deposit material in a location with nothing beneath it, the additive process requires temporary supports that hold up the overhanging material during construction. These supports build simultaneously with the part, providing mechanical structure only during the build process. After completion, supports break away or dissolve, leaving the intended geometry. This temporary support strategy enables creating features that would otherwise require the material to solidify while suspended in mid-air, an obvious impossibility.

The freedom to create moving assemblies that emerge from the printer fully assembled without any assembly operations represents an extreme example of geometric capability enabled by additive construction. A chain with multiple links, each passing through its neighbors, seems to require assembling individual links sequentially. Yet additive manufacturing can build such a chain in a single operation by maintaining narrow gaps between links as each layer constructs. The links build simultaneously but remain separate because the small gaps between them never fill with material. After completion, the chain is fully functional despite never having been assembled.

Lattice structures and complex internal architectures showcase another dimension of design freedom. Rather than making objects solid throughout, designers can fill volumes with intricate three-dimensional lattice patterns that provide strength while dramatically reducing weight. These lattices can vary in density, unit cell geometry, and orientation throughout the part to match local loading conditions or create controlled material properties. Traditional manufacturing would find creating such structures impractical, while additive processes build them as easily as solid regions because both represent just patterns of material deposition at each layer.

Topology optimization algorithms leverage this geometric freedom by removing material from regions where it contributes minimally to structural performance. The resulting organic forms with flowing surfaces, variable cross-sections, and intricate branching structures optimize material distribution for specific loading conditions. These optimized geometries would be prohibitively expensive to manufacture through conventional methods due to their complexity, but they print readily because the layer-by-layer construction process does not distinguish between simple and complex geometries within each cross-section.

However, this design freedom comes with new responsibilities and considerations. Just because additive manufacturing can build almost any geometry does not mean every geometry will build successfully. Understanding how layer orientation affects mechanical properties becomes crucial, as parts are generally weaker across layer boundaries. Minimizing the need for support structures through thoughtful part orientation reduces material waste and post-processing effort. Designing features at scales appropriate to the printing technology ensures reliable construction. The geometric constraints shift rather than disappear, requiring designers to learn new rules specific to additive processes.

Material Efficiency and Waste Reduction

The environmental and economic implications of how efficiently manufacturing processes use raw materials have grown increasingly important as resource prices increase and sustainability concerns influence production decisions. Additive manufacturing’s material efficiency advantage over subtractive methods represents one of its most significant practical benefits, though understanding the full picture requires examining what happens beyond just the primary manufacturing operation.

In subtractive machining, the material removed during cutting operations represents direct waste from the manufacturing perspective. A complex aerospace bracket machined from solid aluminum billet might remove ninety percent of the starting material’s volume, generating vast quantities of chips and turnings. While aluminum scrap has value and gets recycled through remelting, the recycling process itself consumes energy and resources. The economic loss includes not just the material value but also the energy embedded in producing the original billet, which now must be remelted rather than used directly in a finished part.

The buy-to-fly ratio quantifies this waste in aerospace manufacturing, comparing the weight of raw material purchased to the weight of finished parts that fly on aircraft. Traditional machining of aerospace components can produce buy-to-fly ratios of ten to one or higher for complex parts, meaning ten kilograms of raw material produces one kilogram of finished part. Nine kilograms become expensive scrap that must be collected, transported, remelted, and reprocessed into new material. Additive manufacturing can achieve buy-to-fly ratios much closer to one-to-one, using material only where the part requires it.

For expensive materials, this efficiency translates directly into substantial cost savings. Titanium alloys used in aerospace and medical applications cost hundreds of dollars per kilogram in billet form. When ninety percent of that expensive material becomes chips, the waste represents not just environmental impact but significant financial loss. Additive processes that use titanium powder only where needed, with unused powder remaining available for subsequent builds, can reduce material costs dramatically even if the powder itself costs more per kilogram than billet stock.

The support structures required for many additive builds represent the primary source of material waste in the process. Depending on part geometry and orientation, supports might constitute ten to thirty percent of total material consumed. This percentage remains much lower than typical waste rates from subtractive machining, but it represents material used temporarily and then discarded. Minimizing support requirements through optimal part orientation and geometry design reduces this waste. Some additive technologies use dissolvable support materials that wash away after printing, preventing contamination of model material but still representing resource consumption.

Failed prints constitute another source of waste specific to additive manufacturing. When prints fail due to poor adhesion, warping, or other issues, the partially built part and all material deposited up to the failure point becomes waste. For long prints that fail near completion, substantial material and time investment is lost. This failure mode differs from traditional manufacturing where process monitoring and feedback control can detect problems early and adjust parameters before significant waste occurs. Improving first-layer adhesion, optimizing print settings, and implementing monitoring systems that detect failures early helps minimize this waste source.

Powder-based additive technologies like SLS, MJF, and metal powder bed fusion face specific material efficiency challenges related to powder management. Powder exposed to the building process undergoes thermal cycling and potential contamination that can degrade its properties. Manufacturers typically refresh powder beds by removing a percentage of used powder and replacing it with virgin powder for each build. The removed powder may get sieved and reused with further refreshing, but eventually must be retired and potentially reprocessed or disposed of. Managing this powder degradation to balance quality maintenance against material efficiency requires careful process control.

Resin-based additive technologies generate waste through uncured resin that washes off parts during post-processing. This contaminated resin mixed with isopropyl alcohol or other solvents typically cannot be reused and requires disposal according to chemical waste protocols. The volume is relatively small compared to overall resin consumption, but it represents both economic loss and environmental impact from handling and disposal of chemical waste.

Material packaging and delivery systems also affect overall efficiency. FDM filament comes on spools that must be manufactured, shipped, and eventually disposed of or recycled. The cardboard boxes and plastic wrapping used for shipping materials add to the waste stream. Resin bottles and powder containers similarly create packaging waste. While these concerns apply to all manufacturing material supplies, the relatively small batch sizes common in additive manufacturing can create higher packaging waste ratios than bulk material deliveries for traditional manufacturing.

However, the system-level perspective on waste extends beyond just manufacturing operations to include inventory obsolescence, part of life cycles, and product design considerations. Additive manufacturing’s ability to produce parts on demand eliminates waste from maintaining safety stock that may become obsolete when designs change. The design freedom enabling topology optimization creates lighter parts that require less material in the first place and may save energy during their use phase. The ability to print replacement parts locally extends product lifespans by making repairs feasible when replacement parts would otherwise be unavailable. These broader system effects can outweigh the direct manufacturing waste considerations.

Economic Implications of Complexity Independence

One of the most counterintuitive characteristics of additive manufacturing for those accustomed to traditional production is how manufacturing cost relates to part complexity. This relationship fundamentally differs from conventional methods and creates different economic optimization strategies that influence product design and business models.

Traditional manufacturing generally shows direct correlation between part complexity and manufacturing cost. More complex parts require more machining operations, longer cycle times, more sophisticated tooling, tighter process control, and potentially more expensive equipment. A simple turned part with basic cylindrical geometry costs far less to produce than a complex part with intricate features requiring five-axis machining, multiple setups, and specialized fixtures. This cost relationship drives designers toward simplification, standardization, and modularization where complex products assemble from many simple parts rather than integrating functions into fewer complex parts.

Injection molding follows similar patterns where mold complexity directly drives tooling costs. Simple two-cavity molds with basic geometries and straightforward parting lines cost thousands of dollars. Complex molds with intricate details, multiple actions, slides, and lifters can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. This creates strong economic pressure to simplify part geometry even when more complex integrated designs would perform better, because the mold cost dominates the economic equation for anything beyond very high production volumes.

Additive manufacturing inverts this relationship by making geometric complexity essentially free within each layer. A simple cube prints in approximately the same time as an intricate sculpture of equivalent size because both require depositing similar volumes of material across similar heights. The printer does not care whether each layer’s cross-section represents simple geometric shapes or complex organic forms. The computation required to generate tool paths increases with complexity, but this represents seconds or minutes of computer time rather than hours of expensive equipment operation.

This complexity independence profoundly affects how designers approach problems when additive manufacturing will be used for production. Instead of designing an assembly with ten simple parts that bolt together because each simple part is inexpensive to manufacture, designers can create a single integrated part that combines all those functions. The integrated part eliminates assembly labor, reduces part count for inventory management, removes potential failure points at interfaces, and may perform better by eliminating discontinuities. Traditional manufacturing penalizes this approach through higher unit costs for the complex part. Additive manufacturing rewards it by eliminating assembly while adding no manufacturing cost for the complexity.

Part consolidation becomes a common design strategy when leveraging additive manufacturing. Aircraft engine brackets that traditionally assembled from multiple machined or cast parts can be redesigned as single printed components. Medical instruments with multiple small parts and pins can become monolithic devices. Consumer products that required dozen-component assemblies can consolidate into fewer multi-functional parts. Each consolidation reduces assembly time and cost, simplifies inventory management, and eliminates interfaces that can fail.

The economic implications extend to how products are marketed and priced. Traditional manufacturing’s high tooling costs and complexity penalties create pressure to standardize products and limit options because every variant requires different tooling or increases manufacturing complexity. Additive manufacturing’s low setup cost and complexity independence enable mass customization where each unit can differ without cost penalty. This allows business models based on bespoke products, personalization, and made-to-order production that were economically impractical with traditional manufacturing.

However, several qualifications temper the complexity independence principle. While geometric complexity within each layer is essentially free, height complexity directly affects build time since more layers require more time. A tall part takes longer to print than a short part of equivalent volume. Support structure requirements increase with overhanging features, adding material cost and post-processing time. Very fine details may require slower printing speeds or smaller layer heights to resolve accurately, increasing build time. Layer count affects the number of operations the machine performs and therefore scales linearly with part height.

The relationship between complexity and cost also shifts when considering post-processing requirements. Complex internal channels may be impossible to clean or finish. Intricate support structures in difficult-to-reach locations may require extensive hand labor to remove. Parts with many small features may need careful inspection that increases quality control costs. The manufacturing operation itself may not charge more for complexity, but the complete workflow from design to finished part can still accumulate complexity-related costs.

For service bureau pricing models where customers pay for parts produced by contract manufacturers, the pricing structure reflects these considerations. Many bureaus charge based on material volume consumed, build time required, and post-processing complexity. While the basic additive operation shows complexity independence, the overall service cost reflects the total effort involved. Understanding these pricing models helps designers optimize parts not just for additive manufacturing capability but for overall production cost.

Implications for Supply Chain and Distribution

The additive manufacturing principle of building objects layer by layer from digital files rather than forming them with physical tooling creates profound implications for how supply chains operate and how products distribute to end users. These supply chain transformations may ultimately prove more disruptive to existing business models than the direct manufacturing advantages.

Traditional manufacturing supply chains organize around centralized production facilities with expensive specialized equipment and established infrastructure. Raw materials flow into factories, manufacturing operations transform them into finished goods, and distribution networks transport products to regional warehouses and eventually to retail locations or end customers. This model evolved to optimize economies of scale through specialization and volume production, with globalization extending these supply chains across continents to leverage regional advantages in labor costs, material availability, or expertise.

The capital intensity of traditional manufacturing equipment reinforces centralization. Injection molding machines, CNC machining centers, and industrial forming equipment represent substantial investments that only make economic sense when utilized efficiently at high volumes. Companies concentrate this equipment in facilities designed for manufacturing, with supporting infrastructure for material handling, quality control, shipping, and administration. The need to amortize equipment costs across many units drives production batch sizes upward and favors fewer larger facilities over distributed smaller operations.

Additive manufacturing equipment, particularly at the consumer and professional levels, costs orders of magnitude less than equivalent traditional manufacturing capacity. While industrial additive systems remain expensive, entry-level capability costs a few hundred dollars rather than hundreds of thousands or millions required for comparable traditional equipment. This dramatically lower capital requirement enables distributed manufacturing models where production happens at or near point of use rather than in centralized factories.

The implications extend beyond just equipment cost to the economics of inventory and distribution. Traditional manufacturing’s batch-oriented production creates inventory throughout the supply chain. Manufacturers produce quantities exceeding immediate demand to achieve economical batch sizes. Distributors stock products to meet anticipated demand. Retailers maintain inventory to serve customers. All this inventory represents capital tied up in goods that have not yet sold, along with warehousing costs, risk of obsolescence when designs change, and carrying costs that add to final product prices.

Additive manufacturing enables on-demand production that eliminates much of this inventory requirement. Products can be manufactured only when ordered, with digital files serving as virtual inventory that costs nothing to maintain and never becomes obsolete. A replacement part needed for equipment repair can be printed locally from a file rather than shipped from a distant warehouse that must stock parts for equipment that may be decades old. This on-demand model reduces inventory costs, eliminates waste from unsold inventory, and makes economically viable products with sporadic demand that cannot justify maintaining physical inventory.

Distributed manufacturing networks become feasible when production equipment is affordable and production can happen from digital files. Instead of a single factory producing all units of a product and shipping them globally, local service bureaus or micro-factories can download design files and produce parts where needed. This reduces transportation costs and carbon emissions from global logistics, enables faster response to local demand, and increases supply chain resilience by eliminating single points of failure.

The concept of digital warehousing captures this transformation. Rather than storing physical parts in warehouses, companies maintain libraries of digital files that can be transmitted instantly anywhere network connectivity exists. A spare part needed in a remote location downloads in seconds rather than shipping for days or weeks. This becomes particularly valuable for low-demand parts that would otherwise require maintaining expensive inventory with uncertain utilization, for equipment operating in remote locations where shipping is slow or expensive, or for legacy products where manufacturing ceased but support obligations continue.

However, several factors limit how fully additive manufacturing can enable supply chain transformation in the near term. Quality control becomes more challenging in distributed manufacturing where different service bureaus or facilities produce parts from the same files. Ensuring consistent quality across many sites requires careful process qualification, material specifications, and monitoring. Intellectual property concerns arise when digital files must distribute broadly, potentially making designs easier to copy or counterfeit. Regulatory compliance in industries like aerospace, medical devices, or automotive requires documented and validated processes that become harder to maintain across distributed production networks.

The skills and expertise required to operate additive manufacturing equipment effectively also limit how distributed production can become. While consumer 3D printers have become more accessible, producing parts reliably still requires understanding materials, process parameters, and troubleshooting techniques. Professional applications requiring tight tolerances, specific material properties, or regulatory compliance need substantial expertise. This expertise concentrates in specialized service bureaus and manufacturers rather than distributing broadly, partially limiting how decentralized additive manufacturing can become.

Material supply chains present another consideration. While additive manufacturing eliminates tooling, it still requires raw materials in forms specific to each technology. Powder for SLS printing, photopolymer resin for SLA, or filament for FDM must be sourced, qualified, and supplied to wherever production occurs. These material supply chains may become constraints if production distributes too widely, particularly for specialty materials with limited suppliers. The ability to produce locally loses value if materials must still ship globally to reach distributed production sites.

Sustainability and Resource Utilization

Environmental sustainability considerations increasingly influence manufacturing decisions, and understanding how additive manufacturing’s layer-by-layer material addition approach affects resource consumption, energy use, and environmental impact provides important context for technology adoption decisions. The sustainability equation involves complex tradeoffs rather than simple advantages in one direction.

The material efficiency advantages discussed earlier translate directly to reduced resource extraction and processing. Using only the material needed for the finished part rather than machining away excess reduces the primary materials required. For metals, this eliminates the energy-intensive processes of producing larger billets that will mostly become chips. For plastics, it reduces petroleum consumption for polymer production. At scale, these material savings could significantly reduce the environmental footprint of manufacturing if additive methods displace substantial volumes of traditional production.

The localized material deposition characteristic of additive processes creates possibilities for material optimization that traditional manufacturing cannot easily achieve. Functionally graded materials where composition varies continuously through a part allow placing expensive or specialized materials only where performance requires them while using cheaper standard materials elsewhere. Multi-material printing can create parts with different materials in different regions, optimizing each area for its specific function. These capabilities could reduce exotic material consumption by using such materials only where essential.

Energy consumption in additive manufacturing presents a more complex picture. The processes require substantial energy to maintain processing temperatures, power lasers or heating elements, and operate control systems. A 3D printer might consume several hundred watts continuously during builds lasting many hours. Per-part energy consumption depends heavily on build time and whether multiple parts share a build cycle. Research comparing energy consumption between additive and traditional manufacturing shows mixed results depending on specific implementations, with neither approach showing consistent advantage across all scenarios.

However, the full energy picture must include the use phase for many products. If additive manufacturing enables lighter-weight parts through topology optimization or lattice structures, the energy saved during product operation can dwarf manufacturing energy differences. Aircraft components that weigh thirty percent less through optimized design save fuel over millions of flight miles. Automotive parts that reduce vehicle weight improve efficiency over the vehicle’s lifetime. For mobile or aerospace applications, the use-phase energy benefits of lightweight additive components can justify higher manufacturing energy.

The on-demand production model enabled by additive manufacturing reduces waste from inventory obsolescence and the energy associated with warehousing and multiple transportation stages. Products that can be manufactured locally from digital files eliminate transcontinental shipping and the associated fuel consumption and emissions. The ability to print replacement parts that extend product lifespans reduces the environmental impact of manufacturing replacement products. These system-level effects can favor additive approaches even when direct manufacturing energy consumption shows no advantage.

Material recycling presents different challenges and opportunities for additive versus traditional manufacturing. Metal chips from machining operations recycle readily through established infrastructure, though the remelting process consumes energy. Thermoplastic waste from traditional manufacturing often recycles into lower-grade applications. For additive manufacturing, failed prints and support structures from FDM printing can potentially be reprocessed into new filament, though quality may degrade with recycling cycles. Powder-based processes recycle unused powder within certain limits before material degradation requires disposal. Photopolymer resins from SLA printing generally cannot be recycled once cured, creating end-of-life disposal challenges.

The product design implications of additive manufacturing can enhance or reduce sustainability depending on how the technology gets applied. The ability to create customized products that exactly match user needs could reduce waste from products that do not quite fit requirements. The freedom to optimize designs for longevity, repairability, and ultimate disassembly could extend product lifespans and improve recyclability. Conversely, the low cost of prototyping could encourage a throwaway culture where designers produce many iterations without considering their environmental impact, or enable rapid production of novelty items with short useful lives.

Life cycle assessment provides methodology for comprehensively evaluating environmental impacts across a product’s entire existence from raw material extraction through manufacturing, use, and end-of-life disposal. Such assessments for additive manufacturing show that conclusions depend heavily on specific applications, production volumes, material choices, and use-phase considerations. No blanket statement that additive manufacturing is more or less sustainable than traditional methods holds across all circumstances. The key lies in understanding where additive manufacturing’s specific characteristics provide environmental benefits and optimizing technology selection accordingly.

Conclusion

The layer-by-layer additive approach that defines modern 3D printing represents far more than simply a novel way to manufacture objects. This fundamental principle of building up rather than cutting away or forming creates a cascade of consequences that touch every aspect of manufacturing from design freedom through material efficiency, supply chain structure, and sustainability considerations.

Understanding why the additive principle matters requires recognizing how it eliminates constraints that shaped engineering and manufacturing thinking for generations while introducing different considerations that require learning new approaches to design and production optimization. The geometric freedom enabling complex internal features, topology-optimized structures, and integrated multi-functional parts stems directly from the layer-by-layer construction that views objects as sequences of two-dimensional cross-sections rather than complete three-dimensional forms that must be created or extracted all at once.

The material efficiency achieved by depositing material only where needed rather than removing excess creates both economic and environmental benefits, particularly for expensive materials or high-waste-ratio parts. The complexity independence that makes intricate geometries no more expensive to produce than simple shapes inverts traditional design optimization strategies and enables part consolidation and functional integration. The elimination of dedicated tooling and the use of digital files rather than physical molds or fixtures opens possibilities for distributed manufacturing, on-demand production, and mass customization that transform supply chain economics.

Yet these advantages come with new limitations and considerations. The anisotropic properties of layer-by-layer construction require attention to build orientation and loading directions. Support structure requirements add complexity and post-processing effort. Build time correlates with part height in ways that create different economic trade-offs than traditional manufacturing. Material selection remains more limited than the full palette available for conventional processes, though the range continues expanding rapidly.

For anyone involved in product development, manufacturing, or supply chain management, understanding these fundamental principles of additive manufacturing provides the foundation for making informed decisions about when and how to leverage this technology. The layer-by-layer approach does not make additive manufacturing universally superior to traditional methods, but it creates specific capabilities and advantages that prove decisive for particular applications and circumstances. Recognizing these situations and optimizing manufacturing strategy accordingly will increasingly separate successful companies from those constrained by outdated assumptions about how objects must be made.