Introduction

The emergence of three-dimensional printing has fundamentally altered how engineers, product designers, and manufacturers approach the creation of physical objects. Yet despite the enthusiasm surrounding additive manufacturing and its undeniable transformative potential, traditional manufacturing methods developed and refined over centuries continue to dominate production across most industries. This coexistence raises an important question that anyone involved in making physical objects must answer: when does 3D printing provide genuine advantages over conventional manufacturing, and when do traditional methods remain superior?

The answer rarely involves declaring one approach categorically better than the other. Instead, understanding the comparative strengths and limitations of additive manufacturing versus traditional techniques like machining, injection molding, casting, and forming allows informed decisions about which method optimally serves specific project requirements. The factors influencing this choice extend well beyond technical capabilities to encompass economics, timeline constraints, volume requirements, material properties, design complexity, and customization needs.

Traditional manufacturing encompasses a diverse collection of techniques that have evolved over millennia, from ancient casting and forging methods to modern computer-controlled machining and high-precision molding. These established processes excel at producing large quantities of identical parts with excellent material properties, tight tolerances, and surface finishes that meet demanding specifications. The infrastructure supporting traditional manufacturing spans global supply chains, established standards, certified processes, and a massive installed base of equipment representing trillions of dollars of investment.

Three-dimensional printing, conversely, represents a fundamental paradigm shift toward digital manufacturing where designs transform directly into physical objects through additive layer-by-layer construction. This approach eliminates many constraints inherent to traditional manufacturing while introducing different limitations and considerations. The technology continues evolving rapidly, with capabilities expanding, costs declining, and applications multiplying across industries from aerospace to healthcare.

This comprehensive guide examines the critical differences between additive and traditional manufacturing across multiple dimensions including design freedom, production economics, material properties, speed to market, customization capabilities, and environmental impact. By understanding these distinctions, you will gain the insight needed to select the optimal manufacturing approach for your specific projects, whether you are prototyping new product concepts, producing custom components, manufacturing end-use parts, or choosing between in-house fabrication and external production services.

Understanding the Fundamental Paradigm Difference

The most basic distinction between 3D printing and traditional manufacturing lies in whether material gets added or removed during the fabrication process. This fundamental difference creates cascading effects that influence virtually every other aspect of how these technologies operate and where they excel.

Traditional manufacturing predominantly employs subtractive processes where fabrication begins with more material than the finished part requires, and manufacturing removes the excess until the desired shape remains. When a machinist creates a component on a milling machine or lathe, they start with a solid block or bar of material and systematically cut away everything that does not belong to the final part. The cutting tools follow programmed paths that remove material as chips and swarf, gradually revealing the intended geometry hidden within the starting stock.

This subtractive approach imposes inherent constraints on what geometries are practical to manufacture. Cutting tools must physically reach every surface that requires machining, which means internal cavities need access holes, deep pockets require tools with sufficient length-to-diameter ratios to avoid chatter, and undercut features may be impossible to create without multiple setups or specialized tooling. The sequence in which features can be machined matters significantly, as operations performed early in the process affect what becomes possible in subsequent operations.

Injection molding, another dominant traditional manufacturing method, operates through forming rather than cutting but carries its own geometric constraints. Molten plastic or metal injected into a cavity must flow throughout the mold before solidifying, requiring careful consideration of wall thickness uniformity, flow path optimization, and gate placement. The finished part must be extractable from the mold, necessitating draft angles on vertical walls and careful design of undercuts that either require complex mold mechanisms or must be avoided entirely. Each unique part design requires dedicated tooling that represents substantial upfront investment.

Additive manufacturing inverts this paradigm by building objects through material addition rather than subtraction or forming. The 3D printer deposits material only where the final part requires it, constructing the object layer by layer from nothing until the complete form emerges. This approach eliminates many geometric constraints that limit traditional manufacturing. Internal cavities with no external opening, complex lattice structures, parts with moving components that emerge pre-assembled, and organic free-form geometries all become feasible through additive processes that would be difficult or impossible to produce through subtractive machining or molding.

The design freedom enabled by additive manufacturing extends beyond merely making complex geometries feasible. It allows functional optimization without manufacturing constraints dictating design decisions. Engineers can design parts based purely on performance requirements, using topology optimization algorithms to remove material only from locations where it contributes minimally to structural performance. The resulting organic structures with variable cross-sections and intricate internal architectures would be prohibitively expensive or completely impractical to manufacture through traditional methods but print readily on additive equipment.

However, this design freedom carries a cost in terms of other manufacturing considerations. Traditional methods, precisely because they involve established constraints, benefit from decades of design rules, standard practices, and manufacturing knowledge that helps designers create parts optimized for their production method. Additive manufacturing, being newer and less constrained, requires designers to learn different rules about what geometries print successfully, how to orient parts for optimal strength, where support structures become necessary, and how layer-by-layer construction affects material properties.

Production Volume Economics: The Crossover Point

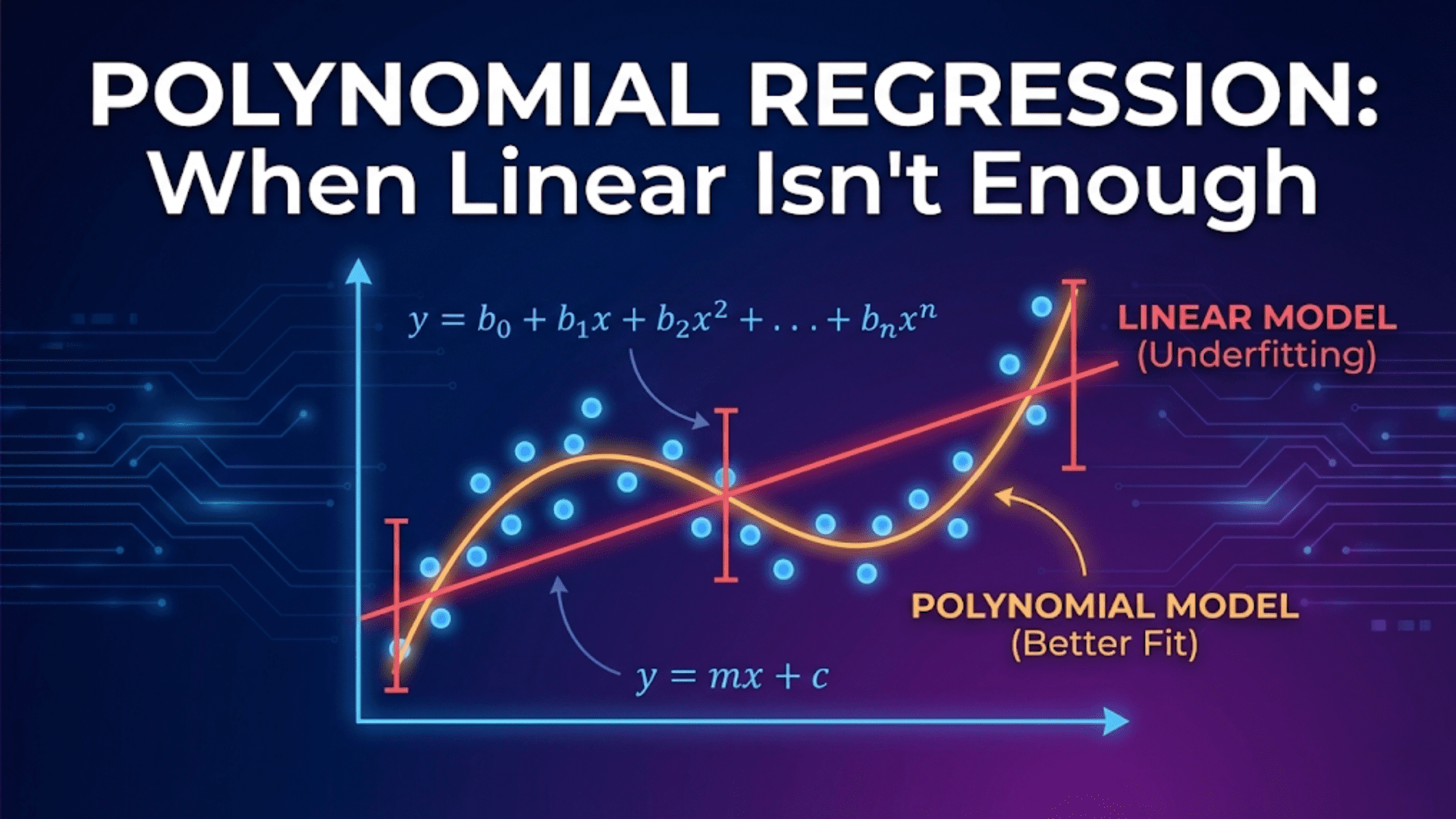

Perhaps no factor influences the choice between additive and traditional manufacturing more significantly than production volume. The economic relationship between these approaches varies dramatically depending on how many identical parts are needed, creating a crossover point below which 3D printing proves more economical and above which traditional manufacturing delivers lower per-part costs.

Traditional manufacturing methods generally require substantial upfront investment in tooling, fixtures, and setup before the first part can be produced. Injection molding provides the clearest example. Creating the steel molds used in injection molding can cost anywhere from ten thousand dollars for simple single-cavity molds to hundreds of thousands of dollars for complex multi-cavity molds with intricate features. Once these molds exist, however, they can produce thousands or millions of parts with individual cycle times measured in seconds or minutes. The expensive tooling cost gets amortized across many parts, driving per-unit costs very low at high volumes.

CNC machining involves less dramatic but still significant setup costs. Programming the machining operations, creating fixtures to hold parts during machining, and setting up the machine tool all require time and expertise before production begins. For one-off parts, these setup costs might equal or exceed the actual machining time. But when producing dozens or hundreds of identical parts, the setup costs distribute across the batch, and the consistency and speed of CNC machining make it very economical.

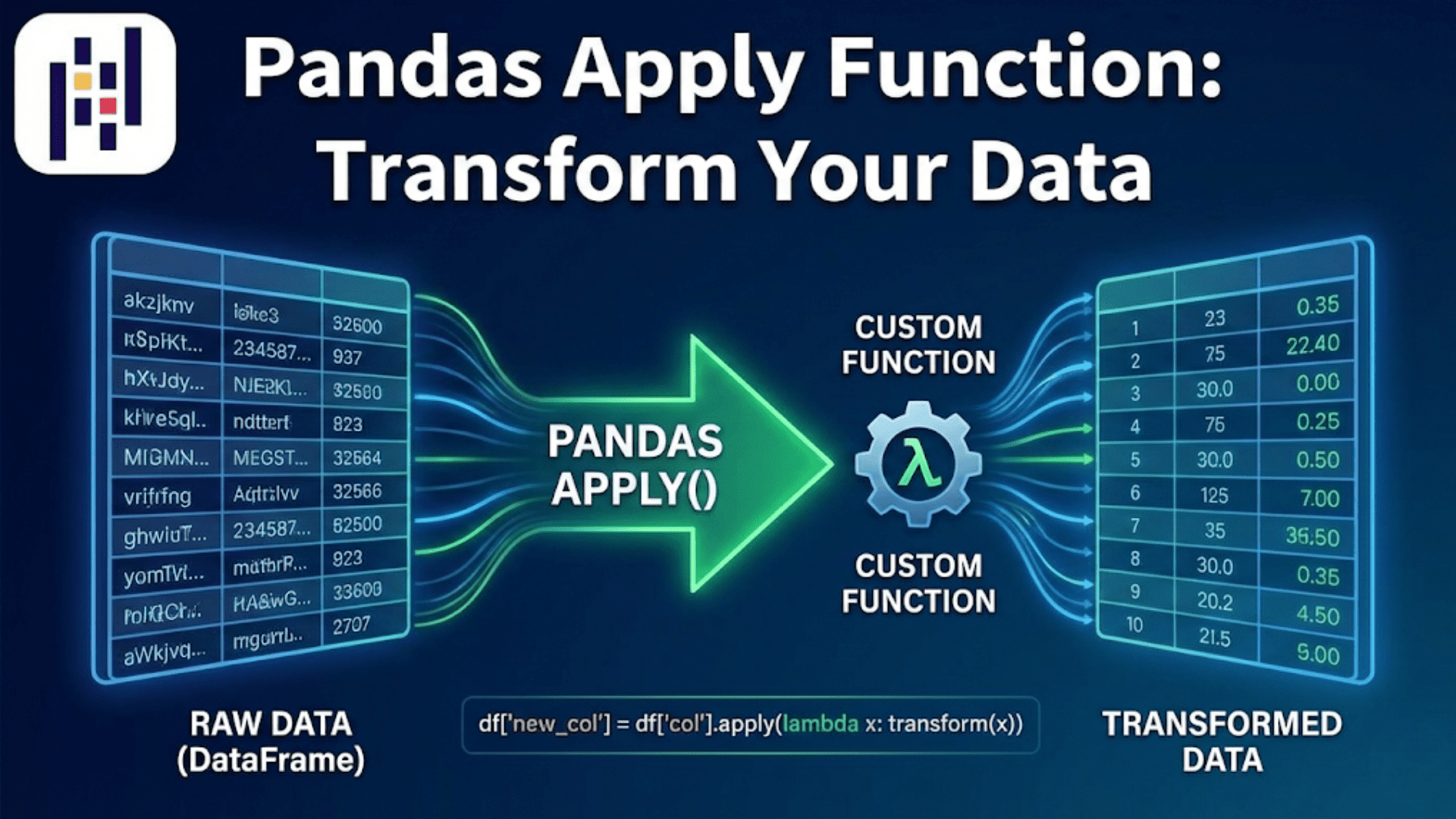

Three-dimensional printing inverts this economic structure by eliminating dedicated tooling entirely. The digital model defines the part geometry, and changing from one part design to another requires only loading a different file. No molds to create, no fixtures to build, no machine tool setup to perform. This means the first part costs essentially the same as the hundredth part. The economic advantage of 3D printing becomes overwhelming for small quantities where traditional manufacturing’s tooling costs cannot be justified.

The break-even point between these approaches varies depending on the specific part, material, required production rate, and quality standards. For simple plastic parts, injection molding might become economically competitive with 3D printing somewhere between one hundred and one thousand parts. More complex parts with expensive molds shift the crossover point higher, potentially into thousands of parts before molding achieves cost parity with printing. Conversely, very simple parts that mold quickly in inexpensive tooling might favor molding at even lower volumes.

Metal parts show similar patterns when comparing 3D printing to machining. For prototype quantities of one to ten parts, printing often proves faster and cheaper than programming and running CNC operations. As quantities increase into dozens or hundreds, machining costs per part decline while printing costs remain relatively constant, eventually making machining more economical. The specific crossover depends on part complexity, material, and required surface finish.

An important consideration often overlooked in simple cost comparisons is the total project timeline. Even when traditional manufacturing offers lower per-part costs for a given quantity, the time required to create tooling might make that cost advantage irrelevant. If a product design needs validation through physical testing before committing to production tooling, 3D printing can produce functional prototypes in days that would require weeks or months to produce through tooled processes. This speed advantage allows more design iterations in the same timeline, potentially improving the final product enough to justify higher unit costs for the prototypes.

The economic equation also changes when considering the risk of design changes. Tooling investments for traditional manufacturing become sunk costs if design modifications prove necessary. Discovering that an injection-molded part needs a dimensional change or added feature after investing in expensive tooling creates difficult decisions about whether to scrap and remake the tooling or accept a compromised design. With 3D printing, design changes cost nothing more than the time to modify the digital model and print a new part, making iterative development much less financially risky.

Some companies adopt hybrid strategies that leverage the strengths of both approaches across a product’s lifecycle. Early prototypes and design validation parts get 3D printed to maximize iteration speed and minimize risk. Once the design stabilizes, bridge tooling or soft tooling allows limited production through molding or casting at volumes where printing becomes impractical but full production tooling remains unjustified. Finally, after validating market demand and finalizing the design, investment in production-grade tooling enables high-volume manufacturing at optimal unit costs.

Material Properties and Performance Characteristics

The materials available and the properties achievable represent another critical dimension for comparing additive and traditional manufacturing. Different applications demand specific material characteristics, and the manufacturing method significantly influences what material properties the finished parts exhibit.

Traditional manufacturing works with the full spectrum of engineering materials in their optimized forms. Metals used in machining include tool steels, stainless steels, aluminum alloys, titanium, brass, and dozens of other alloys optimized for specific property combinations of strength, corrosion resistance, thermal conductivity, or wear resistance. Injection molding processes virtually any thermoplastic polymer along with some thermosets, offering designers access to materials engineered for specific applications from food-safe polypropylene to flame-retardant ABS to fiber-reinforced nylon.

The manufacturing process itself has minimal effect on material properties in traditional methods. A piece of aluminum exhibits essentially the same strength, stiffness, and thermal properties whether cut from plate stock on a mill or extruded into bar stock. Injection-molded plastic parts have consistent properties governed primarily by the polymer formulation rather than the molding process, though factors like mold temperature, injection pressure, and cooling rate can influence crystallinity and molecular orientation.

Additive manufacturing, conversely, works with a more limited material palette, and the layer-by-layer building process itself affects final part properties in ways that matter for engineering applications. FDM printing with thermoplastic filament creates parts with anisotropic mechanical properties, meaning strength varies depending on the direction of applied load. Parts are generally weakest when forces try to separate layers because the layer-to-layer bonding represents the weakest link in the structure. This directional strength characteristic requires careful consideration when designing load-bearing components for 3D printing.

The materials available for FDM printing, while expanding continuously, still represent a subset of the thermoplastics available for injection molding. Standard PLA and ABS cover many applications but lack the engineering properties of high-performance polymers like PEEK, PEI, or liquid crystal polymers. Specialty filaments attempt to bridge this gap, with nylon filaments providing better strength and wear resistance, polycarbonate filaments offering impact resistance, and composite filaments incorporating carbon fiber or glass fiber for enhanced stiffness. However, even these advanced filaments typically underperform compared to their injection-molded equivalents because the printing process introduces porosity and the layer boundaries create inherent weakness.

Resin-based 3D printing technologies like SLA produce parts with more isotropic properties than FDM since the photopolymerization process creates chemical bonds between layers rather than relying on thermal bonding. However, photopolymer resins generally exhibit more brittle behavior than engineering thermoplastics, limiting their suitability for applications involving impact loading or stress concentrations. Specialized tough or engineering resins attempt to address these limitations, and some newer resin formulations achieve properties approaching or matching injection-molded plastics, but material costs increase substantially for these high-performance resins.

Powder bed fusion technologies like SLS and MJF produce parts with excellent mechanical properties that approach or match injection molding performance. PA12 nylon printed through SLS exhibits strength, toughness, and fatigue resistance suitable for many functional applications, and the layer bonding is strong enough that parts can be considered nearly isotropic. This makes SLS attractive for end-use part production where mechanical performance matters. The material selection remains more limited than injection molding, but the available materials cover a useful range from standard nylon to glass-filled variants to flexible TPU.

Metal 3D printing introduces another dimension to the material property discussion. Technologies like selective laser melting or electron beam melting can produce metal parts with mechanical properties that equal or exceed traditionally manufactured equivalents. The rapid solidification inherent to these processes can create fine-grained microstructures with beneficial properties. However, the layer-by-layer construction can introduce preferred grain orientations, residual stresses, and porosity that require careful process control and often post-processing heat treatment to achieve optimal properties.

For applications where material properties are critical and well-characterized materials are required, traditional manufacturing generally offers advantages. Aerospace applications often require materials with certified properties and documented consistency that meet stringent specifications. Medical implants need biocompatible materials with proven long-term performance. Automotive components must withstand temperature extremes and chemical exposure with predictable behavior. In these demanding applications, the mature material science and established supply chains supporting traditional manufacturing provide greater confidence than the newer and less standardized materials available for additive manufacturing.

Conversely, some applications benefit specifically from the unique material structures that additive manufacturing can create. Lattice structures with controlled porosity can match the density profile of human bone for orthopedic implants, achieving biomechanical properties impossible with solid materials. Functionally graded materials with composition or properties varying continuously through the part enable optimization impossible with homogeneous materials. These capabilities, while niche, represent genuine advantages that additive manufacturing brings to specific applications.

Speed to Market and Iteration Velocity

The timeline from initial concept to finished parts represents another critical comparison dimension where additive and traditional manufacturing show complementary strengths for different phases of product development. The speed advantage can shift depending on whether the goal is producing initial prototypes, validating designs through testing, or manufacturing production quantities.

For prototype development and design validation, 3D printing provides unmatched speed. A product designer can complete a CAD model in the morning, send it to a 3D printer in the afternoon, and have physical parts in hand by the next morning. This rapid turnaround enables iterative design cycles that would be impractical with traditional manufacturing. Testing a part might reveal that a feature needs to be two millimeters longer, or an assembly might show that components interfere in ways not obvious from CAD. With 3D printing, modifying the digital model and printing updated parts requires only hours or days.

Traditional manufacturing imposes much longer lead times for initial parts. Creating the program for CNC machining requires time, especially for complex parts with many features. Setting up the machine, selecting appropriate tools and fixtures, and running test pieces to verify the program all add to the timeline. For machined prototypes, one to two weeks from design completion to parts in hand would be considered fast. Injection-molded prototypes require even longer timelines because prototype molds must be designed and manufactured before the first part can be produced, potentially adding weeks or months to the process.

This speed advantage for prototyping allows design teams to explore more variations and make better-informed decisions before committing to production. Instead of choosing between two design concepts based on analysis alone, teams can print both versions, conduct physical testing, and make decisions based on measured performance. The ability to quickly produce multiple iterations improves final product quality by allowing validation of assumptions that might prove incorrect only when physically tested.

However, as projects transition from prototyping to production, the speed equation changes. Traditional manufacturing methods designed for volume production can achieve cycle times that far exceed 3D printing speeds. An injection molding machine might produce a plastic part every thirty seconds, while 3D printing that same part might require two hours. For producing hundreds or thousands of parts, traditional manufacturing’s higher production rate becomes decisive despite the slower initial setup.

The timeline advantage also depends on part complexity in interesting ways. Simple parts with minimal features might machine quickly but take as long to 3D print as complex parts with intricate details, since print time depends primarily on volume and height rather than geometric complexity. This means 3D printing’s speed advantage increases with design complexity. A highly detailed sculptural form might require extensive machining time with multiple setups but prints in the same time as a simple block of equivalent size.

For bridge production, where quantities are too large for economical 3D printing but too small to justify production tooling, methods like vacuum casting or urethane casting offer compromises. These processes use 3D printed master patterns to create silicone molds that can produce dozens of cast copies. The master pattern prints quickly, the mold-making adds a few days, and then parts can be cast in batches. This hybrid approach extends the viable volume range for rapid production while maintaining reasonable unit costs.

Some manufacturing scenarios require on-demand production where parts are made only when needed rather than produced in batches and inventoried. Spare parts for equipment with long service lives represent a classic case where on-demand manufacturing makes sense. Three-dimensional printing excels in this application because parts can be produced from digital files without maintaining physical inventory or minimum order quantities. When a repair requires a specific part, the digital file downloads and prints overnight, avoiding weeks of conventional manufacturing lead time or the cost of warehousing inventory for decades.

Design Complexity and Geometric Freedom

One of the most profound advantages that additive manufacturing brings to product development is the liberation from many geometric constraints that traditional manufacturing imposes on design. This freedom allows engineers and designers to optimize parts for function rather than manufacturability, though it requires learning new design rules specific to additive processes.

Traditional subtractive manufacturing fundamentally limits what geometries are practical to create. Machining requires tool access to every surface, which means internal cavities must have openings large enough for tools to enter, deep pockets need sufficient diameter for tool clearance, and undercuts may require special setups or prove impossible entirely. Parts often require multiple setups where the workpiece gets repositioned to access different faces, adding complexity and cost while introducing potential alignment errors between operations.

These constraints directly influence product design in ways engineers sometimes accept without conscious recognition. A housing designed for machining will have parallel walls with draft angles, avoid undercuts, and use standard drilled holes rather than complex internal geometries. These design decisions reflect manufacturing constraints rather than optimal functional design. The part works acceptably because the designer accommodated these limitations, but a better design might exist if manufacturing constraints did not apply.

Injection molding imposes different but equally significant geometric constraints. Parts must be extractable from molds, requiring draft angles on walls, eliminating severe undercuts, and maintaining relatively uniform wall thickness for consistent flow and cooling. Complex molds with slides and lifters can create some features that violate simple extraction rules, but these mechanisms add substantial cost and complexity. Multi-material parts require overmolding or insert molding processes with their own constraints. The mold cost increases dramatically with part complexity, creating economic pressure to simplify designs even when functional performance would benefit from greater complexity.

Three-dimensional printing removes many of these constraints by building parts layer by layer without requiring tool access or mold extraction. Internal channels can wind through a part in arbitrary paths with no external opening. Lattice structures can fill volumes with controlled density gradients that would be impossible to cast or machine. Parts can include moving mechanisms like hinges or chains that emerge from the printer pre-assembled without any assembly operation. Organic free-form surfaces with continuously varying curvature present no particular difficulty compared to simple geometric shapes.

This geometric freedom enables topology optimization, where algorithms remove material from regions contributing minimally to structural performance while maintaining material where stresses concentrate. The resulting organic structures often show forms reminiscent of natural structures like bone or plant growth patterns, with material arranged efficiently to resist loads with minimal weight. These optimized geometries would be prohibitively expensive or impossible to manufacture through traditional methods but print readily with additive processes.

Lattice structures represent another design possibility that additive manufacturing uniquely enables. These periodic or aperiodic cellular structures can fill volumes with controlled density, creating parts that are lightweight yet strong. The unit cell geometry, size, and distribution can vary throughout the part to create functionally graded structures with properties tuned to local requirements. Applications range from lightweight structural components in aerospace to impact-absorbing structures in helmets to scaffolds in medical implants that promote bone ingrowth.

However, this geometric freedom comes with new constraints specific to additive manufacturing that designers must understand. Overhanging features require support structures that must be removed after printing, potentially leaving surface marks. Very thin features may prove difficult to build reliably depending on the printing technology and material. Layer-by-layer construction creates inherent anisotropy in FDM parts that affects strength. Understanding these additive manufacturing-specific constraints becomes essential for designing parts that not only can be printed but will perform satisfactorily in their intended application.

The design approach itself changes when working with additive manufacturing. Traditional design-for-manufacturing principles emphasize simplifying geometry, standardizing features, and minimizing complexity to reduce cost. Additive manufacturing design principles recognize that geometric complexity is essentially free, shifting focus toward functional optimization and consolidation. Instead of designing an assembly with multiple simple parts that connect together, an additive approach might create a single complex part that integrates multiple functions, reducing assembly time and potential points of failure while leveraging the geometric freedom additive processes provide.

Customization and Personalization Capabilities

The ability to customize each manufactured part without additional cost represents one of additive manufacturing’s most transformative capabilities. This characteristic fundamentally changes what becomes economically feasible in terms of personalization and opens entirely new categories of products and services that traditional manufacturing cannot address efficiently.

Traditional manufacturing achieves economic efficiency through economies of scale. The more identical units produced, the lower the cost per unit becomes as tooling costs amortize across larger quantities and production processes optimize for repetition. This economic structure inherently discourages customization because each variant requires separate tooling, setup, or configuration. Producing one hundred identical parts costs far less per unit than producing one hundred customized parts with unique features.

This limitation means traditionally manufactured products tend toward standardization. Clothing comes in standard sizes. Prosthetic devices use off-the-shelf components with limited adjustment ranges. Consumer products offer limited color or feature variations rather than true customization. Custom products exist but command premium prices that reflect the additional manufacturing cost, limiting their market to applications where that premium is justified.

Three-dimensional printing eliminates the economic penalty for variation. Since no tooling exists and the digital model defines the part, changing that model costs nothing beyond the time required for the modification. Printing one hundred identical parts costs the same as printing one hundred unique parts assuming they use similar material quantities and build time. This characteristic enables mass customization where each manufactured unit can be unique without substantially affecting production costs.

Medical applications illustrate this advantage compellingly. Dental laboratories can 3D print surgical guides customized to each patient’s anatomy based on CT scan data. Hearing aids can be manufactured with shells molded precisely to each patient’s ear canal geometry. Orthopedic implants can match the bone structure being replaced. Prosthetic sockets can conform exactly to the residual limb shape. Each of these applications requires a unique geometry for each patient, making them natural fits for additive manufacturing despite traditional methods being able to produce individual instances of these products.

Consumer products increasingly leverage mass customization through 3D printing. Custom-fitted athletic shoes can be manufactured based on foot scans. Eyeglass frames can be designed to match facial geometry and aesthetic preferences. Jewelry can incorporate personalized details like names or dates at no additional cost. Game miniatures can be customized with specific equipment, poses, or features chosen by the customer. The ability to offer this customization without the traditional cost penalty creates differentiation and customer value.

Production applications benefit from customization capabilities as well. Manufacturing fixtures and jigs can be designed specifically for each production run or product variant rather than using generic fixtures that compromise efficiency. End-of-arm tooling for robots can be optimized for specific tasks. Replacement parts can be modified to correct issues found in the original design without requiring new tooling. These applications leverage customization to improve efficiency or capability rather than aesthetic personalization.

The workflow for mass customization typically involves parametric design where key dimensions or features can be adjusted through variables rather than requiring complete redesign for each variant. A prosthetic socket design might use parameters for limb diameter, length, and specific anatomical features measured from scans. Eyeglass frames might parameterize temple length, bridge width, and lens positioning. Software can automate the customization process, generating unique models from measurement data or customer specifications without requiring designer intervention for each unit.

However, customization introduces complexities beyond the manufacturing process itself. Quality control becomes more challenging when every part is unique, as traditional inspection against specifications assumes all parts should match nominal dimensions. With customized parts, each unit has different target dimensions, requiring more sophisticated inspection approaches. Data management grows more complex when tracking unique parts rather than standard part numbers. Documentation and traceability require systems that associate each manufactured unit with its specific design data and customer.

The regulatory environment for some industries presents additional challenges for customization. Medical devices must demonstrate safety and effectiveness, but when each device is custom, validating every unique instance is impractical. Regulatory frameworks are evolving to address this, establishing validated design envelopes within which customization can occur without requiring individual approval for each device. Similar challenges exist in other regulated industries where customization must balance with standardization requirements for safety or compliance.

Environmental Impact and Sustainability Considerations

As environmental concerns increasingly influence manufacturing decisions, comparing the sustainability implications of additive versus traditional manufacturing provides important context for technology selection. Both approaches have environmental impacts that depend heavily on specific implementations, materials, energy consumption, and waste generation.

Material efficiency represents one of the clearest sustainability advantages of additive manufacturing. Traditional subtractive processes remove material as waste, with machining operations sometimes converting seventy or eighty percent of starting stock into chips and swarf. While metal chips can be recycled and plastic waste can sometimes be reprocessed, recycling requires energy and resources, and some materials lose properties through recycling. Additive manufacturing uses material only where the final part requires it, generating minimal waste during the building process itself.

For FDM printing, the primary waste comes from support structures that must be removed from completed parts. These supports typically account for ten to thirty percent of material used depending on part geometry and orientation. Some support material can be recycled back into filament, though quality may degrade. Resin-based printing generates waste through uncured resin that washes off parts during cleaning, though this represents a small fraction of total material consumption. Powder bed fusion technologies recycle unused powder efficiently, with only the material actually fused into parts being consumed.

Energy consumption presents a more complex comparison. Additive manufacturing equipment requires substantial energy to maintain processing temperatures, power lasers or heating elements, and run control systems. A 3D printer might consume several hundred watts continuously during builds that can run for many hours. Traditional manufacturing equipment also consumes significant energy, with CNC machine tools using hundreds or thousands of watts during operation. Per-part energy consumption depends greatly on utilization rates, with idle time consuming energy without producing parts.

Life cycle analysis provides more comprehensive environmental assessment by considering impacts from raw material extraction through end-of-life disposal. For some products, additive manufacturing enables lighter-weight designs through topology optimization or lattice structures, and the energy saved during the product’s use phase can exceed the manufacturing energy even if manufacturing itself consumed more energy than traditional methods. Aircraft components illustrate this tradeoff, where 3D printed parts that save weight reduce fuel consumption over the aircraft’s lifetime by amounts that dwarf the manufacturing energy difference.

The ability to manufacture parts on demand rather than maintaining inventory carries sustainability implications through reduced warehousing, transportation, and inventory obsolescence. Traditional manufacturing’s batch-and-queue model often requires producing parts in larger quantities than immediate demand to achieve economical unit costs. These parts then sit in warehouses consuming space and potentially becoming obsolete if designs change. Additive manufacturing’s economic structure allows printing parts only when needed, reducing inventory carrying costs and waste from obsolete inventory.

Local manufacturing enabled by additive technology reduces transportation impacts by allowing parts to be manufactured near where they will be used rather than shipping them globally. A replacement part needed in a remote location can be printed locally from a digital file rather than shipped from a distant warehouse. This distributed manufacturing model reduces the fossil fuel consumption and emissions associated with global logistics networks.

However, additive manufacturing materials themselves present sustainability challenges. Many 3D printing materials are petroleum-derived plastics with similar environmental impacts to conventionally manufactured plastics. Bio-based materials like PLA offer renewable content, but end-of-life disposal remains challenging as these materials may not biodegrade in landfill conditions despite being derived from renewable resources. Recycling infrastructure for 3D printing materials remains underdeveloped compared to traditional plastics, though initiatives are emerging to collect and reprocess failed prints and support materials.

The longevity and repairability of additive manufactured products affects their sustainability profile. If 3D printed parts prove less durable than traditional equivalents and require more frequent replacement, any manufacturing efficiency gains may be offset by shorter product lifetimes. Conversely, the ability to print custom repair parts or replacement components can extend product lifespans beyond what would be practical if replacement parts must be specially ordered or machined.

The rapid obsolescence cycle of consumer 3D printing equipment raises sustainability concerns as older printers get discarded when newer models offer improved capabilities. The electronics and mechanical components in these machines contain materials that should be recycled but often end up in waste streams. Traditional manufacturing equipment typically has longer service lives measured in decades, amortizing the environmental impact of equipment production across much longer periods.

Quality Control and Consistency Considerations

Quality and consistency represent critical factors in manufacturing where traditional and additive methods show distinct characteristics that matter for different applications. The ability to repeatedly produce parts that meet specifications with predictable variation determines whether a manufacturing process can be trusted for demanding applications.

Traditional manufacturing benefits from decades of process development, standardization, and quality control methodology. Statistical process control methods developed for mass production provide frameworks for monitoring variation, identifying trends, and maintaining processes within specified limits. Operators understand how machine wear, tool condition, material variation, and environmental factors affect quality. Standards exist for surface finish, dimensional tolerance, and material properties specific to each manufacturing method.

The consistency of traditional manufacturing derives partly from using raw materials that are themselves products of mature quality-controlled processes. Metal stock conforms to alloy specifications with documented chemistry and properties. Injection molding resins meet documented specifications for physical properties, flow characteristics, and consistency. These characterized inputs allow manufacturers to predict output characteristics with confidence based on extensive experience and data.

Additive manufacturing, being newer, has less mature quality control infrastructure. Process parameters that affect print quality are numerous and interact in complex ways. Layer height, print speed, temperature settings, material characteristics, environmental conditions, and machine calibration all influence final part quality. Understanding these interactions and maintaining consistent results requires expertise that continues developing across the industry.

Variability between machines presents challenges for additive manufacturing. Two printers of the same model might produce slightly different results from the same file due to calibration differences, wear patterns, or environmental conditions. Traditional manufacturing equipment shows variation as well, but decades of standardization work have established practices for qualifying equipment and maintaining consistency. Additive manufacturing standards continue evolving but remain less mature.

Material consistency represents another source of variation in additive manufacturing. Filament diameter can vary within and between spools, affecting extrusion rate and therefore part quality. Resin properties can change with age or exposure to light. Powder characteristics like particle size distribution and moisture content affect sintering quality. While material manufacturers work to improve consistency, the specifications and quality control for additive materials generally lag behind traditional materials.

Process monitoring and closed-loop control remain less developed for additive manufacturing compared to traditional methods. CNC machine tools routinely monitor cutting forces, spindle power, and tool wear to detect problems and adjust parameters. Injection molding machines measure cavity pressure, temperature, and cycle time to ensure consistent fills. Many 3D printers operate largely open-loop, executing programmed commands without sensing whether the actual result matches expectations. Advanced industrial additive systems increasingly incorporate monitoring, but consumer and intermediate equipment typically lacks sophisticated sensing.

Post-process inspection methods for additive parts continue developing. Traditional inspection techniques like coordinate measuring machines can verify external dimensions, but internal features like lattice structures or channels may be difficult or impossible to inspect without destructive testing. X-ray computed tomography provides volumetric inspection of internal features but requires expensive equipment and substantial time per part. Non-destructive evaluation methods specifically for additive parts remain an active area of development.

The combination of higher process variability and less mature inspection methods means additive manufactured parts may show greater unit-to-unit variation than traditionally manufactured equivalents. For applications where consistency is critical, this represents a genuine limitation. Aerospace and medical applications that require rigorous quality documentation may find it more challenging to validate additive processes than traditional methods with established histories.

However, the digital nature of additive manufacturing creates opportunities for quality improvement that traditional methods lack. Every machine setting and parameter can be logged, creating complete digital records of how each part was manufactured. This traceability enables correlation of process conditions with part quality, facilitating continuous improvement. Digital twins that simulate the building process can predict problems before printing begins. Machine learning algorithms can analyze historical data to optimize parameters for specific geometries or quality requirements.

Making the Decision: Selection Criteria and Hybrid Approaches

With understanding of how additive and traditional manufacturing compare across multiple dimensions, making informed decisions about which approach to use for specific projects requires systematic evaluation of requirements against the strengths and limitations of each method.

Production volume remains the primary economic driver. For quantities from one to perhaps a few dozen parts, additive manufacturing typically provides faster turnaround and lower cost by eliminating tooling requirements. As quantities increase toward hundreds or thousands, traditional manufacturing’s ability to amortize tooling costs and achieve faster cycle times makes it progressively more economical. The specific crossover volume depends on part complexity, material, required quality, and production timeline.

Design complexity affects the economic calculation because traditionally difficult-to-manufacture geometries may add significant cost to conventional production while costing no more to 3D print. A part with complex internal features might require substantial machining time with multiple setups, making even low-volume production expensive through traditional methods. The same part might print quickly with additive technology. Conversely, a simple part might machine very quickly but take as long to print as a complex part.

Material requirements influence technology selection significantly. If the application demands a specific alloy, polymer, or composite that is only available in traditional manufacturing forms, the decision is straightforward. If material properties need to meet documented specifications for regulated applications, the mature material science supporting traditional manufacturing provides advantages. If the application can work with materials available for additive manufacturing and benefits from that technology’s other advantages, material availability does not constrain the choice.

Surface finish and dimensional accuracy requirements may favor one approach over another. Parts requiring fine surface finish or tight tolerances may achieve specifications more readily through machining or molding, though post-processing can improve additively manufactured parts. Parts where as-printed surface texture is acceptable or where geometry makes inspection difficult benefit from additive approaches that create those geometries more easily.

Timeline considerations matter greatly in product development contexts. The ability to iterate designs quickly through rapid prototyping can compress development schedules significantly even if production eventually uses traditional manufacturing. The time saved in development may justify higher unit costs for prototypes. For some projects, speed to market matters more than optimizing production costs, favoring technologies that enable faster iterations.

Customization requirements create strong advantages for additive manufacturing when each unit needs unique features. Mass customization applications naturally favor additive approaches where variation costs no additional per-unit expense. Traditional manufacturing remains competitive when standardization allows leveraging economies of scale.

In practice, many manufacturing strategies employ both traditional and additive methods at different stages or for different components. Early product development uses 3D printing for rapid iteration and validation. Low-volume initial production might continue with additive manufacturing or transition to bridge tooling approaches like cast urethane. High-volume production eventually justifies production tooling for traditional manufacturing. This staged approach optimizes technology selection for each phase rather than committing to a single approach throughout the product lifecycle.

Hybrid manufacturing systems that combine additive and subtractive processes in a single machine tool represent another approach to leveraging strengths of both methods. These systems might additively build a near-net-shape part, then machine critical surfaces to achieve required finish and tolerances. Or they might add material to existing parts, creating features or repairs that extend part life. This hybrid approach remains relatively specialized but shows promise for applications that benefit from both additive and subtractive capabilities.

Conclusion

The comparison between three-dimensional printing and traditional manufacturing reveals not a simple superiority of one approach over the other but rather complementary capabilities that serve different needs effectively. Traditional manufacturing excels at producing large quantities of parts with excellent material properties, tight tolerances, and low unit costs once tooling investments are amortized. The mature processes, established materials, and extensive infrastructure supporting conventional manufacturing make it the logical choice for high-volume production of standardized parts.

Additive manufacturing transforms the economics and capabilities of low-volume production, complex geometries, rapid iteration, and mass customization. The elimination of tooling costs makes small quantities economically viable. The freedom from conventional geometric constraints enables functional optimization and design consolidation. The speed from digital model to physical part accelerates development cycles. The ability to customize each unit without cost penalty enables personalization and applications serving unique individual requirements.

Understanding these distinctions empowers better manufacturing decisions. The question is not which technology is better in absolute terms but which better serves the specific requirements of each project considering volume, geometry, material, timeline, quality, and customization needs. In many cases, the optimal strategy employs both approaches at different stages or for different components, leveraging the unique strengths each technology brings.

As additive manufacturing continues maturing with expanding materials, improving process control, declining equipment costs, and growing applications, the circumstances favoring its selection will broaden. However, traditional manufacturing will continue dominating high-volume standardized production where its advantages remain decisive. The future likely involves deeper integration of both approaches rather than replacement of traditional methods with additive alternatives. By understanding when each technology excels, manufacturers can make informed decisions that optimize cost, quality, timeline, and capability for their specific needs.