Introduction

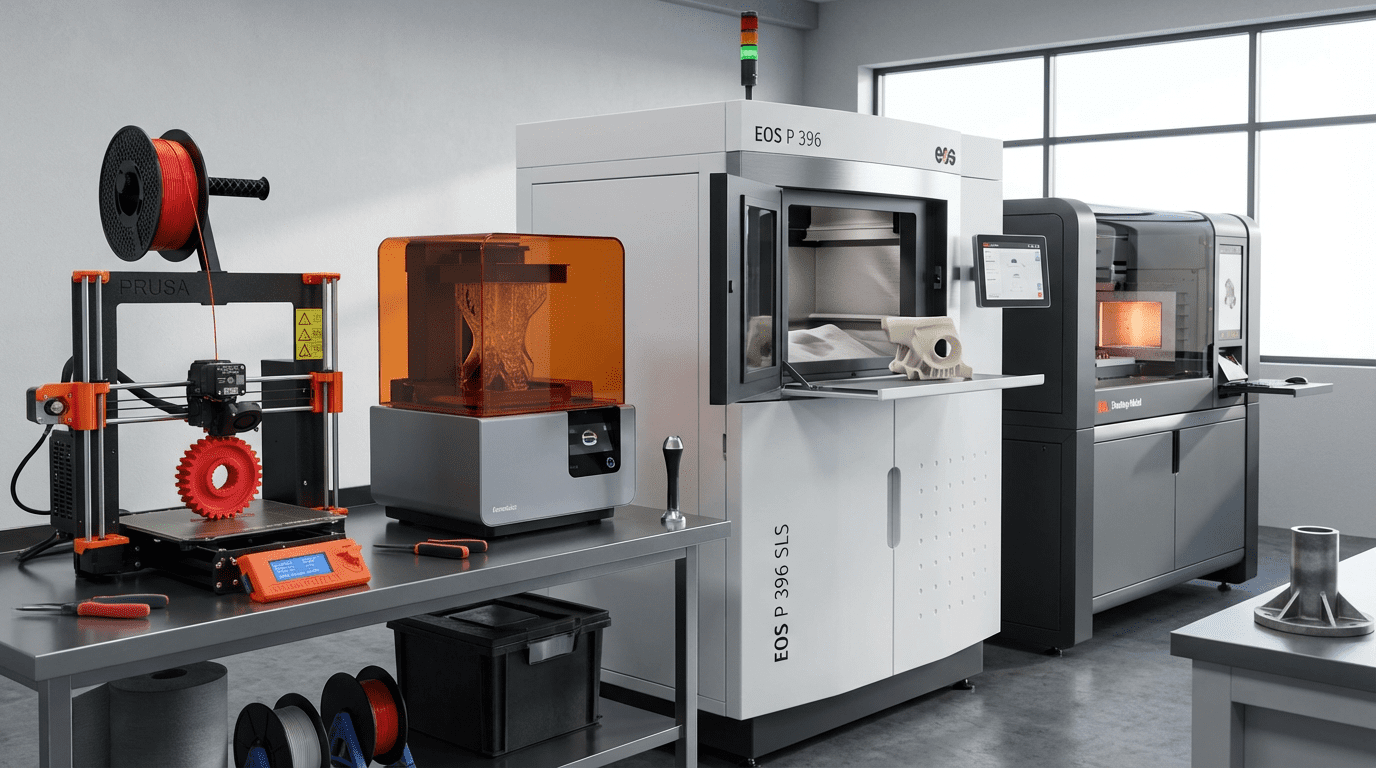

When most people encounter the term “3D printing” for the first time, they naturally imagine a single unified technology that works the same way across all machines. This assumption makes sense given how we casually group many diverse technologies under simple umbrella terms. When someone mentions “photography,” we understand they might be referring to film cameras, digital sensors, instant cameras, or smartphone imaging, yet we recognize all these approaches serve the fundamental purpose of capturing images.

The world of three-dimensional printing operates similarly. While all 3D printing technologies share the core principle of building objects layer by layer through additive manufacturing, the specific methods used to create those layers vary dramatically. Some technologies melt plastic wire and deposit it through nozzles. Others use lasers to solidify liquid resin or fuse powder particles. Some build objects from the bottom up, while others grow downward from a platform. Each approach carries distinct advantages and limitations that make it suitable for particular applications while less ideal for others.

Understanding these different technologies matters because selecting the appropriate printing method for a given project can mean the difference between exceptional results and disappointing failures. The technology that produces perfect prototypes for product design might prove completely unsuitable for manufacturing end-use parts. The process that excels at creating jewelry with intricate detail cannot efficiently produce large structural components. And the equipment that fits comfortably in a home workshop operates on completely different principles than industrial systems that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through the major categories of 3D printing technologies, explaining how each one works, what materials it uses, where it excels, and what limitations constrain its applications. By understanding these fundamental differences, you will be equipped to make informed decisions about which technology suits your specific needs, whether you are considering purchasing equipment, selecting a service bureau for production, or simply trying to understand what makes various printing methods unique.

Fused Deposition Modeling: The Accessible Foundation

Fused Deposition Modeling, universally abbreviated as FDM and sometimes called Fused Filament Fabrication or FFF, represents the most widespread and accessible form of 3D printing technology available today. If you have seen a consumer 3D printer in someone’s home, a school classroom, or a community makerspace, you almost certainly encountered an FDM machine. This technology has achieved dominant market position in the consumer and hobbyist space because it strikes an effective balance between capability, affordability, ease of use, and material cost that other technologies struggle to match.

The fundamental operating principle of FDM involves feeding solid plastic filament into a heated nozzle that melts the material into a semi-liquid state. This melted plastic extrudes through a small opening at the nozzle tip as the print head moves precisely across the build area, depositing thin lines of material that quickly cool and solidify. Layer builds upon layer, with each new layer bonding to the one beneath it, until the complete three-dimensional object emerges.

The materials used in FDM printing come as long continuous strands of thermoplastic wound onto spools, typically in standardized diameters of either 1.75 millimeters or 2.85 millimeters. The most common material, PLA or polylactic acid, offers ease of use, minimal warping, and reasonable strength for many applications. It prints at relatively low temperatures around 200 degrees Celsius and produces minimal odor during processing. ABS, or acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, provides greater toughness and temperature resistance but requires higher printing temperatures around 240 degrees Celsius and benefits from enclosed printing environments to prevent warping. PETG combines ease of printing similar to PLA with strength and chemical resistance closer to ABS, making it popular for functional parts.

Beyond these standard materials, the FDM ecosystem includes an extensive variety of specialty filaments. Flexible materials like TPU create rubber-like parts with varying degrees of shore hardness. Nylon offers exceptional strength and wear resistance for mechanical applications. Polycarbonate provides impact resistance and high-temperature tolerance. Specialty filled filaments incorporate wood fibers, metal particles, carbon fiber, or glow-in-the-dark pigments to create unique properties or aesthetics. This material diversity allows FDM printing to address an enormous range of applications from decorative objects to functional engineering components.

FDM technology excels in several areas that explain its popularity. The equipment costs remain accessible, with functional printers available for a few hundred dollars and highly capable machines in the thousand-dollar range. Material costs stay reasonable, with basic filament available for twenty to thirty dollars per kilogram. The printing process is relatively forgiving and straightforward to learn, allowing beginners to achieve successful prints without extensive training. Parts can be quite large, as build volumes on consumer FDM printers commonly range from 200 to 300 millimeters in each dimension, with some machines offering even larger capabilities.

The technology also shows impressive versatility in the types of objects it can produce. From simple household items to complex mechanical assemblies with moving parts, from artistic sculptures to functional engineering prototypes, FDM handles diverse requirements effectively. The ability to print in multiple colors through manual filament changes or automatic filament switching systems adds creative possibilities. Some advanced FDM systems can even print with multiple materials simultaneously, creating objects with varying properties in different regions.

However, FDM printing carries inherent limitations that users must understand. Surface finish quality shows visible layer lines that create a striated texture on all surfaces. While these lines can be minimized through smaller layer heights or removed through post-processing like sanding, they represent a fundamental characteristic of the technology. The layer-by-layer building process creates anisotropic mechanical properties, meaning parts are weaker when forces try to separate layers compared to forces acting parallel to layer lines. Print speed represents another constraint, as building objects layer by layer simply takes time, with moderately complex prints often requiring several hours to complete.

The precision and dimensional accuracy of FDM printing, while impressive for an additive process, falls short of what machining or molding can achieve. Tolerances typically range around plus or minus 0.2 millimeters for consumer equipment, which suffices for many applications but proves inadequate for precision engineering work. Support structures required for overhanging features must be removed after printing, potentially leaving marks or requiring cleanup that affects final part quality.

Stereolithography: Precision Through Photopolymerization

Stereolithography, commonly abbreviated as SLA, represents one of the oldest 3D printing technologies, having been invented in the 1980s, yet it continues to evolve and find new applications thanks to its ability to produce parts with exceptional detail and smooth surface finishes. This technology operates on completely different principles than FDM, using light to selectively harden liquid resin rather than depositing melted material through a nozzle.

The fundamental process involves a vat filled with photosensitive liquid resin. This resin contains special chemical compounds called photoinitiators that react to ultraviolet light by triggering a polymerization reaction. When UV light strikes the liquid resin, the exposed areas undergo a chemical change that transforms them from liquid to solid plastic. The SLA system uses a precisely controlled light source, typically either a laser beam or a specialized UV projector, to illuminate specific locations in the resin vat corresponding to each layer’s cross-section.

Two main configurations exist for SLA printing, distinguished by their build orientation. Traditional SLA machines use a “top-down” approach where the build platform starts just below the surface of the resin vat. A laser traces out the first layer’s pattern on the resin surface, hardening it. The platform then descends deeper into the vat by one layer height, a coating blade or roller spreads fresh liquid resin over the just-cured layer, and the laser traces the next layer. This pattern continues with the part growing downward into the resin vat.

More recent consumer SLA printers often use an inverted “bottom-up” configuration. Here, the resin vat has a transparent window at the bottom, and the UV light source shines upward through this window. The build platform starts very close to the window, and the light cures resin in the thin gap between the platform and window. After each layer cures, the platform lifts slightly to allow fresh resin to flow into the gap, then lowers back down for the next layer to cure. The part grows upward, hanging from the build platform.

The materials used in SLA printing are specially formulated photopolymer resins designed to cure rapidly and completely when exposed to UV light. Standard resins produce rigid parts with smooth surfaces and good detail resolution, making them popular for visual prototypes and display models. Tough resins formulate to provide greater impact resistance and flexibility, approaching the mechanical properties of engineering plastics like ABS. Flexible resins create rubber-like parts for gaskets, grips, and other applications requiring compliance. Castable resins are designed to burn out cleanly, making them ideal for creating patterns for jewelry casting or investment casting processes.

Specialized SLA resins address specific industry needs. Dental resins meet biocompatibility requirements for applications like surgical guides, models for orthodontics, and temporary crowns. High-temperature resins withstand elevated temperatures for applications like injection molding tooling or under-hood automotive components. Transparent resins create clear or tinted parts for lenses, light pipes, or demonstration models where internal features need visibility. Engineering resins provide properties like chemical resistance, high stiffness, or electrical insulation for functional prototypes and end-use parts.

SLA technology offers several compelling advantages that explain its adoption in professional environments. Surface quality represents perhaps the most obvious benefit, as SLA parts emerge from the printer with smooth surfaces free from the layer lines that characterize FDM prints. Detail resolution reaches impressive levels, with many SLA systems capable of reproducing features smaller than 100 microns. This combination of smooth surfaces and fine detail makes SLA ideal for applications like jewelry prototyping, dental models, miniature figurines, and any situation where visual quality matters significantly.

The isotropy of SLA parts, meaning they have similar mechanical properties in all directions, contrasts with the directional weakness of FDM parts. Because each layer fully cures and chemically bonds to the previous layer through continuing polymerization, SLA parts do not suffer from the same layer adhesion weaknesses that affect FDM prints. This results in more predictable mechanical behavior and parts that can withstand multi-directional stresses more reliably.

Dimensional accuracy in SLA printing typically exceeds what FDM can achieve, with well-calibrated systems holding tolerances within 0.1 millimeters or better. This precision makes SLA suitable for applications requiring accurate fit between mating parts or precise replication of detailed geometries. The technology handles complex geometries with fine features, thin walls, and intricate details that would challenge FDM printing.

However, SLA printing carries distinct limitations and requirements that affect its practicality for certain users. The liquid resin materials cost significantly more than FDM filament, often ranging from one hundred to two hundred dollars per liter. Post-processing requirements add complexity and time to the workflow, as parts must be washed in isopropyl alcohol or other solvents to remove uncured resin from surfaces, then undergo additional UV curing to complete the polymerization process fully. This post-processing requires dedicated equipment like wash stations and curing chambers.

The resins themselves require careful handling. Uncured resin can cause skin irritation or allergic reactions, necessitating gloves and good ventilation during machine operation and post-processing. The odor, while not as strong as some other chemicals, can be noticeable in workspace environments. Resin has limited shelf life, particularly once exposed to light, as it can spontaneously cure over time in storage. The vats used in SLA printers have a transparent film or window that can become clouded or damaged over time, requiring periodic replacement.

Build volumes on consumer SLA printers generally run smaller than comparably priced FDM machines, typically in the range of 100 to 150 millimeters in the horizontal dimensions. While larger industrial SLA systems exist with build volumes measured in hundreds of millimeters, these machines carry price tags that place them well beyond hobbyist budgets. The printing process itself runs slower than FDM for many objects, particularly when printing tall parts, as each layer requires time for the curing reaction to complete and for the platform to lift and lower between layers.

The material properties of photopolymer resins differ from the thermoplastics used in FDM printing in ways that matter for some applications. Most resins are more brittle than thermoplastics like ABS or PETG, making them prone to fracture under impact or stress concentration. Resin parts can degrade when exposed to UV light over extended periods, causing discoloration and embrittlement. Temperature resistance typically falls short of engineering thermoplastics, with many resins beginning to soften or deform at temperatures that would not affect FDM materials.

Digital Light Processing: Speed Through Projection

Digital Light Processing, commonly called DLP, represents a close cousin to SLA technology, using the same fundamental principle of curing liquid photopolymer resin with UV light but employing a different approach to illumination that offers certain advantages. While SLA systems typically use a laser that must trace out each layer point by point, DLP technology uses a digital projector to flash the entire layer’s image simultaneously across the build area. This distinction creates meaningful differences in how the technologies perform.

The light source in DLP printers consists of a digital micromirror device, essentially a specialized chip containing an array of thousands of tiny mirrors. Each mirror can tilt independently to reflect light either toward the build area or away into an absorber. By precisely controlling which mirrors reflect light and which do not, the system creates a complete image of the layer being printed. This image projects through the transparent window at the bottom of the resin vat, curing an entire layer in one brief exposure rather than tracing it sequentially.

This parallel processing approach gives DLP printing a significant speed advantage for many objects compared to laser-based SLA. Since the entire layer exposes simultaneously, the time per layer remains constant regardless of how much area that layer covers. A tall cylindrical part with small cross-section takes the same time per layer as a wide plate that fills the entire build area. In contrast, laser-based SLA must spend more time tracing larger areas, making print time proportional to the cross-sectional area being cured.

The materials used in DLP printing are essentially identical to those used in SLA, as both technologies cure photopolymer resins through UV exposure. Any resin formulated for SLA will typically work in DLP systems, and many resin manufacturers do not distinguish between the two technologies in their product offerings. This interchangeability gives DLP users access to the same diverse material library that SLA users enjoy.

The advantages of DLP technology mirror those of SLA in many respects. Surface finish quality, detail resolution, mechanical isotropy, and dimensional accuracy all reach similar levels between the two technologies when properly calibrated equipment is used. The primary distinction lies in the speed advantage DLP offers for certain geometries and the fact that DLP’s voxel-based imaging creates perfectly smooth surfaces within each layer, whereas laser-based SLA may show slight texture from the laser path overlap.

DLP printing shares most of the limitations inherent to resin-based additive manufacturing. Material costs, post-processing requirements, handling precautions, build volume constraints, and material property considerations all apply similarly to DLP as to SLA. One additional consideration specific to DLP relates to the projector light source. The lamps or LED arrays used in projectors have finite lifespans, requiring eventual replacement, and the projector optics must be carefully calibrated to ensure even light intensity across the entire build area for consistent curing.

The resolution characteristics of DLP differ slightly from SLA in how they scale across the build area. In laser-based SLA, the focused laser spot maintains consistent size regardless of where it traces within the build volume, giving uniform resolution everywhere. In DLP, the projector divides the build area into a fixed grid of pixels, and resolution depends on how many pixels span the build area. The same projector chip used over a smaller build area gives finer resolution than when used over a larger area. This means DLP printers must balance build size against resolution, with larger build volumes coming at the cost of lower resolution or requiring more expensive projectors with higher pixel counts.

Selective Laser Sintering: Industrial Powder Processing

Selective Laser Sintering, abbreviated as SLS, represents a more industrial approach to additive manufacturing that operates on entirely different principles than the technologies discussed so far. Rather than working with melted thermoplastic filament or liquid photopolymer resin, SLS uses fine powder material that sits in a large heated chamber. A high-powered laser selectively fuses powder particles together in precise patterns corresponding to each layer’s geometry, building objects within a bed of loose powder that both supports the part during building and provides the raw material for construction.

The process begins with a thin layer of powder spread across the build platform using a roller or blade mechanism that ensures uniform thickness and density. The build chamber maintains elevated temperature just below the melting point of the powder material, reducing the energy the laser needs to fuse particles and minimizing thermal stress in the parts being built. A computer-controlled laser beam scans across the powder bed, following paths calculated by the slicing software, heating the powder along these paths to its melting or sintering temperature. The powder particles fuse together where the laser touches, creating a solid cross-section of the part being built.

After completing one layer, the build platform lowers by the height of one layer, fresh powder spreads across the top, and the laser traces the next layer. This cycle repeats with the part growing upward within the powder bed. The loose unfused powder surrounding the part serves as support material, holding up overhanging features and complex geometries without requiring separate support structures. This self-supporting nature represents one of SLS’s most significant advantages, enabling geometric freedom that surpasses even SLA.

When the build completes, the entire powder bed must cool gradually to prevent thermal stress from causing warping or cracking in the parts. After cooling, the parts are excavated from the loose powder, and this excess powder can be sieved, mixed with fresh powder, and reused for subsequent builds. The parts typically require bead blasting or other surface treatment to remove powder particles that cling to surfaces.

Nylon, specifically PA12 nylon, represents the most common material for SLS printing, offering an excellent combination of strength, flexibility, durability, and relatively low cost. Parts printed in nylon exhibit properties similar to injection-molded nylon components, with good impact resistance, fatigue resistance, and wear characteristics. The slightly porous surface texture that results from the sintering process can be desirable for certain applications or treated through infiltration or coating if denser surfaces are required.

Other powder materials expand SLS capabilities into specialized applications. Glass-filled nylon adds stiffness and reduces thermal expansion for applications requiring dimensional stability. TPU powder creates flexible parts with rubber-like properties. Various composite powders incorporate carbon fiber, aluminum, or other fillers to modify mechanical, thermal, or electrical properties. Some high-end SLS systems can even process metal powders, though this capability typically requires different equipment configurations with inert atmosphere chambers and more powerful lasers.

The advantages of SLS technology make it attractive for professional prototyping and production applications despite the high equipment costs. The self-supporting nature of powder bed printing eliminates the need for support structures, which both simplifies post-processing and enables geometric freedom. Complex internal channels, intricate lattice structures, moving assemblies, and virtually any conceivable geometry can be produced without the constraints support requirements impose on other technologies.

Mechanical properties of SLS parts approach or match those of traditional manufacturing methods. The parts are isotropic and strong in all directions, without the layer adhesion weaknesses that affect FDM or the brittleness concerns that affect many resin materials. The nylon material provides good chemical resistance, reasonable temperature tolerance, and excellent long-term durability. Parts can function as end-use products rather than just prototypes, making SLS viable for low-volume manufacturing, custom production, and spare parts applications.

Build efficiency in SLS systems can be remarkably high because multiple parts can nest together within the powder bed, sharing the same build cycle. An SLS machine might produce dozens or even hundreds of small parts simultaneously by packing them efficiently within the build volume. This amortizes the substantial per-build costs across many parts, potentially making SLS economically competitive with other manufacturing methods for appropriate production volumes.

However, SLS technology carries significant limitations that have kept it largely confined to professional and industrial users. Equipment costs run extremely high, with functional SLS systems starting around one hundred thousand dollars and industrial machines costing several hundred thousand dollars or more. This price barrier places SLS equipment far beyond the reach of hobbyists and small businesses.

Material costs also run higher than FDM filament, and the powder handling requirements add complexity to the workflow. Fresh powder must be carefully stored to prevent moisture absorption, used powder must be sieved to remove debris and mixed with fresh powder at appropriate ratios, and powder handling creates dust that requires ventilation and cleanup. The build process itself takes substantial time, not just for the laser scanning but also for the extended cooling period required after the build completes.

Surface finish from SLS printing has a distinctive slightly grainy or sandpaper-like texture resulting from the sintered powder particles. While this texture can be acceptable or even desirable for some applications, achieving smooth surfaces requires post-processing through tumbling, bead blasting, or coating. The parts also tend to have lower detail resolution than SLA or DLP, with fine features less well-defined due to the powder particle size and thermal effects during sintering.

Multi Jet Fusion: HP’s Powder Innovation

Multi Jet Fusion, or MJF, represents a relatively recent innovation in powder bed printing developed by Hewlett-Packard. This technology competes directly with SLS for professional prototyping and production applications but uses a fundamentally different approach to fusing powder. Instead of using a laser to selectively heat powder, MJF employs an inkjet-style print head that selectively deposits agents onto the powder bed. One agent, called the fusing agent, absorbs infrared energy and causes powder to melt when exposed to heating lamps. Another agent, the detailing agent, reduces fusion in specific locations to create sharp edges and fine details.

The MJF process spreads a thin layer of powder across the build platform, then print heads pass over the surface depositing fusing agent in areas that should become solid parts. After agent deposition, infrared lamps pass over the layer, flooding the entire surface with thermal energy. The powder coated with fusing agent absorbs this energy and melts, while untreated powder remains largely unaffected. The detailing agent deposits at the boundaries of parts to prevent thermal bleeding that would blur edges. This cycle repeats for each layer, with the part building up within the powder bed similar to SLS.

The material used in commercially available MJF systems is primarily PA12 nylon, similar to SLS, providing comparable mechanical properties and applications. HP continues to develop additional materials including glass-filled variants and TPU, gradually expanding the material palette. The parts emerging from MJF systems show properties very similar to SLS parts, with good strength, isotropy, and durability suitable for functional applications.

MJF offers several advantages over traditional SLS. Build speed can be significantly faster because the agent deposition and heating process completes more quickly than laser scanning for each layer. Part detail and edge sharpness sometimes exceed what SLS achieves thanks to the detailing agent that controls thermal spread at boundaries. Mechanical properties are consistent and predictable, matching or slightly exceeding SLS benchmarks. Build efficiency remains high with the ability to pack multiple parts within each build.

The limitations of MJF closely parallel those of SLS. Equipment costs remain very high, restricting the technology to professional service bureaus and industrial users. Material costs and handling requirements are similar. Surface finish shows comparable texture requiring post-processing for smooth surfaces. The technology remains relatively new compared to SLS, meaning the material library is smaller and long-term experience is more limited.

Material Jetting: Precise Multi-Material Printing

Material jetting technologies, sometimes called PolyJet printing after Stratasys’s implementation, operate on principles similar to inkjet paper printing but deposit photopolymer materials that cure under UV light rather than ink on paper. Print heads containing hundreds of tiny nozzles jet microscopic droplets of liquid photopolymer onto the build platform in precise patterns. UV lamps mounted on the print head cure each layer immediately after deposition, solidifying the liquid droplets into solid material. Layer builds upon layer until the complete part emerges.

The most distinctive capability of material jetting is its ability to mix different materials within a single part. The print heads can deposit different photopolymers simultaneously, including specialized support materials that dissolve in water or sodium hydroxide solution after printing. Some systems can even mix materials in controlled ratios to create gradient properties or composite structures with varying characteristics in different regions. This multi-material capability enables creating parts with regions of different colors, different mechanical properties like rigid and flexible zones, or different transparency levels.

Materials for material jetting include standard rigid photopolymers in various colors and opacity levels, flexible rubber-like materials with different shore hardnesses, transparent clear materials, simulated engineering plastics that mimic ABS or polypropylene properties, and high-temperature materials. Specialized materials include dental and medical-grade photopolymers meeting biocompatibility requirements and castable materials that burn out cleanly for jewelry or dental applications.

Material jetting produces exceptionally smooth surfaces and very fine detail resolution, often achieving layer heights as thin as 16 microns. Parts emerge from the printer with minimal visible layer lines and can accurately reproduce fine features, sharp edges, and smooth curves. The ability to print in full color or with material property gradients opens creative possibilities unavailable with other technologies. Dimensional accuracy rivals or exceeds SLA, making material jetting suitable for applications requiring precise fit and geometric fidelity.

However, material jetting shares the general limitations of photopolymer systems regarding brittleness, UV degradation, and temperature resistance. Material costs run very high, typically hundreds of dollars per liter, and the requirement for both model and support materials increases cost further. Equipment prices place professional material jetting systems well into the six-figure range, though more accessible systems have recently entered the market at lower price points. The parts typically require post-processing to remove support material, though the dissolvable supports make this less labor-intensive than mechanical support removal.

Binder Jetting: Speed and Scale

Binder jetting represents another powder-based technology that achieves additive manufacturing through a completely different mechanism than SLS or MJF. This technology spreads layers of powder similar to SLS, but instead of using thermal energy to fuse powder particles, it uses inkjet print heads to selectively deposit liquid binder agent onto the powder. The binder causes powder particles to stick together, creating a solid mass where the binder deposits while leaving untreated powder loose. After the build completes, parts undergo furnace sintering to burn off the binder and fuse powder particles metallurgically.

Binder jetting works with a very wide range of powder materials because the binding process does not rely on specific thermal properties. Sand, ceramics, metals, and various composite powders can all be processed through binder jetting. This material flexibility enables diverse applications from foundry sand molds to metal parts to full-color sandstone models.

For metal printing, binder jetting offers significant advantages over laser-based metal processes. Build speeds can be very high since depositing binder is faster than laser melting. The lack of intense localized heating reduces thermal stress and allows larger parts. Multiple parts can pack efficiently within the powder bed to maximize build efficiency. Material waste is minimal as unfused powder can be reused after sieving.

The process involves several distinct stages beyond the initial printing. After completing a build, the parts, still fragile and held together only by binder, must undergo careful excavation from the powder bed. They then go through a curing stage where heat drives off solvents and hardens the binder. For metal parts, a subsequent sintering stage in a furnace burns off the binder entirely and fuses the metal powder particles, creating fully dense metal parts. This sintering causes significant shrinkage, typically fifteen to twenty percent, which must be accounted for in the original digital model.

The strengths of binder jetting include high build speeds, large build volumes in industrial systems, material versatility, and the ability to produce full-color parts when using appropriate powder and binder combinations. For metal production, binder jetting avoids many of the thermal stress issues that affect laser-based metal printing. The technology scales well to volume production as build times do not increase dramatically with part complexity or quantity within the build volume.

Limitations include the multi-stage post-processing requirement that adds time and complexity. The shrinkage during sintering requires careful compensation and makes achieving tight tolerances challenging. Material properties of sintered parts depend heavily on process control during sintering. Surface finish is typically rougher than other additive processes, requiring post-processing for smooth surfaces. Equipment costs remain high for professional systems, though some more affordable binder jetting printers have entered the market for specific applications like full-color models.

Choosing the Right Technology for Your Needs

With this understanding of how different 3D printing technologies work and what distinguishes them, selecting the appropriate method for a specific application becomes a matter of matching technology strengths to project requirements while accepting the limitations that each approach carries.

For hobbyists, educators, and users prioritizing accessibility and versatility, FDM printing typically represents the optimal starting point. The low equipment and material costs, straightforward learning curve, and ability to produce a wide range of useful objects make FDM ideal for exploration and general-purpose printing. The visible layer lines and anisotropic properties rarely matter for the household items, educational models, and creative projects that constitute most hobbyist printing.

When visual quality, fine detail, or smooth surfaces become primary requirements, resin-based technologies like SLA or DLP offer clear advantages despite their higher costs and handling requirements. Product designers creating presentation models, jewelers producing castable patterns, dental laboratories making surgical guides, and miniature enthusiasts printing tabletop gaming figures all benefit from the superior surface quality and detail resolution that photopolymer printing delivers.

Professional prototyping applications that demand strong functional parts with good mechanical properties often turn to SLS or MJF technology despite the high equipment costs. The self-supporting powder bed eliminates geometric constraints, and the nylon material provides properties suitable for functional testing. Design engineers can create prototypes that accurately represent production part behavior, and some prototypes can even serve as end-use parts for low-volume applications.

Multi-material requirements or applications demanding the highest precision naturally lead toward material jetting technology. Creating prototypes that combine rigid and flexible materials, producing full-color anatomical models for medical applications, or making detailed patterns requiring no post-processing support removal all play to material jetting’s strengths.

Large-scale production of metal parts may benefit from binder jetting’s speed advantages and lack of thermal stress, particularly when part geometries are complex and production volumes justify the infrastructure investment required. Conversely, foundries creating sand molds for metal casting find binder jetting’s ability to produce complex molds quickly very attractive.

Understanding that no single technology optimally addresses all additive manufacturing needs helps explain why the industry supports multiple competing approaches. Each technology occupies distinct niches where its particular balance of capabilities, limitations, and costs provides optimal value. As the technologies continue evolving, with equipment costs declining, material options expanding, and process capabilities improving, the applications where additive manufacturing makes sense continue to grow across all these technological branches.

Conclusion

The diversity of technologies operating under the umbrella term “3D printing” reflects the reality that additive manufacturing encompasses many distinct physical processes, each with unique characteristics that make it suitable for specific applications while less optimal for others. FDM builds objects from melted thermoplastic filament deposited through nozzles, offering accessibility and versatility. SLA and DLP cure liquid photopolymer resin with UV light, delivering exceptional surface quality and detail. SLS and MJF fuse powder particles in heated chambers, producing strong functional parts with geometric freedom. Material jetting deposits and cures multiple materials for multi-material capabilities. Binder jetting binds powder particles for high-speed production, particularly in metals.

Understanding these fundamental differences empowers users to make informed decisions about which technology suits their specific needs. The hobbyist building functional household items requires different capabilities than the product designer creating presentation models, who in turn needs different attributes than the medical professional producing patient-specific guides. Recognizing that a single technology cannot optimally serve all these diverse requirements helps explain the continued coexistence and evolution of multiple additive manufacturing approaches.

For those beginning their journey into three-dimensional printing, starting with accessible FDM technology provides a foundation for understanding additive manufacturing principles while producing useful results. As experience grows and requirements become more specialized, exploring other technologies becomes possible through service bureaus that offer access to industrial equipment without the capital investment ownership requires. This path allows users to leverage the strengths of multiple technologies, selecting the optimal process for each project rather than constraining all work to the capabilities of a single machine.

The remarkable achievement that all these diverse technologies share is their ability to transform digital designs directly into physical objects through automated additive processes. Whether melting plastic, curing resin, fusing powder, or binding particles, each approach has democratized aspects of manufacturing that previously required extensive tooling, specialized equipment, and significant capital investment. This democratization continues expanding as technologies mature, costs decline, and new applications emerge across industries from aerospace to medicine, from consumer products to education. Understanding how these technologies differ provides the knowledge needed to participate effectively in this ongoing transformation of how we design, prototype, and manufacture objects.