Introduction

Every time you flip a light switch, charge your smartphone, or turn on your computer, you are harnessing one of the most transformative discoveries in human history. Electricity powers virtually every aspect of modern civilization, yet for many people, it remains a mysterious and invisible phenomenon. Understanding what electricity truly is forms the essential foundation for anyone interested in electronics, whether you are taking your first steps into this fascinating field or simply want to comprehend the technology that surrounds you daily.

This comprehensive guide will demystify electricity by exploring it from the ground up, starting with the atomic structure that makes electrical phenomena possible and building toward a practical understanding of how electricity behaves in circuits. Rather than overwhelming you with complex mathematics or abstract physics, we will focus on developing an intuitive mental model that helps you truly grasp this invisible force that has revolutionized human existence.

The Atomic Foundation: Where Electricity Begins

To understand electricity, we must start by examining the fundamental building blocks of all matter. Everything you see around you, from the device you are reading this on to the air you breathe, consists of atoms. These incredibly tiny structures contain three types of particles, each playing a crucial role in electrical phenomena.

The Three Particles That Make Electricity Possible

At the center of every atom sits the nucleus, a dense core containing protons and neutrons. Protons carry a positive electrical charge, which we can think of as a fundamental property of matter, similar to how objects have mass. Neutrons, as their name suggests, remain electrically neutral and do not directly participate in electrical phenomena, though they are essential for atomic stability.

Orbiting this nucleus at tremendous speeds are electrons, particles that carry a negative electrical charge. These electrons exist in specific energy levels or shells surrounding the nucleus, somewhat like planets orbiting a star, though the quantum mechanical reality is far more complex. The electrons in the outermost shell, called valence electrons, are the true heroes of our electrical story. These outer electrons are loosely bound to their parent atoms and can be influenced by external forces, making them mobile under the right conditions.

Under normal circumstances, atoms contain equal numbers of protons and electrons, making them electrically neutral overall. The positive charge of the protons exactly balances the negative charge of the electrons. However, when we disturb this balance by adding or removing electrons, we create conditions that allow electricity to flow.

Materials and Their Relationship with Electron Flow

Not all materials interact with electrons in the same way, and this difference creates three broad categories that are crucial for understanding electrical circuits. Conductors are materials where valence electrons can move freely from atom to atom with minimal resistance. Metals like copper, silver, aluminum, and gold excel as conductors because their atomic structure allows electrons to roam through the material like water flowing through a pipe. This property makes them ideal for wires and electrical connections.

Insulators represent the opposite extreme. Materials like rubber, plastic, glass, and ceramic hold their electrons tightly, preventing them from moving freely. This electron-trapping characteristic makes insulators perfect for coating wires and creating barriers that confine electrical flow to desired paths. When you see the colored plastic coating on electrical wires, you are looking at an insulator doing its job of keeping electricity where it belongs.

Between these extremes lie semiconductors, materials with conductivity that falls somewhere in the middle and can be precisely controlled. Silicon and germanium are the most famous semiconductors, forming the foundation of modern electronics. Their unique properties allow us to create transistors, diodes, and integrated circuits that can switch and amplify electrical signals with remarkable precision. The semiconductor revolution transformed electricity from a simple force for powering motors and lights into a medium for processing information and creating the digital world we inhabit today.

Defining Electricity: Movement and Energy

With our atomic foundation established, we can now answer the central question directly. Electricity, in its most fundamental sense, is the flow of electrical charge, typically carried by moving electrons. When we force electrons to move in a coordinated direction through a conductor, we create an electrical current. This movement does not happen spontaneously but requires an energy source to push the electrons along their path.

Think of electricity as being similar to water flowing through a pipe. Just as water molecules move from high pressure to low pressure, electrons move through conductors when we create a difference in electrical potential between two points. This potential difference, which we call voltage, acts as the driving force that compels electrons to move. The actual quantity of electrons flowing past a given point per second represents the electrical current.

Static Electricity Versus Current Electricity

Electricity manifests in two primary forms that behave quite differently. Static electricity occurs when electrical charges accumulate on the surface of materials without flowing. When you shuffle your feet across a carpet on a dry day and then touch a metal doorknob, the sudden discharge you feel and the spark you might see represent static electricity equalizing between your body and the grounded doorknob. This type of electricity involves charges that remain stationary until they find a path to discharge suddenly.

Current electricity, in contrast, involves charges that flow continuously through a conductor. This is the type of electricity that powers your home, charges your devices, and makes electronics possible. Rather than building up and discharging abruptly like static electricity, current electricity maintains a steady flow as long as we provide a complete path, called a circuit, and a continuous source of electrical pressure to push the charges along.

The distinction between these two forms helps explain why touching a doorknob after building up static charge delivers a sharp but harmless shock, while touching a live electrical wire carrying current electricity can be extremely dangerous. The continuous nature of current electricity means energy transfer happens at a much more dangerous rate than the brief discharge of accumulated static charge.

The Essential Quantities: Voltage, Current, and Resistance

Understanding electricity requires familiarity with three fundamental quantities that describe how electrical energy behaves in circuits. These three measurements form the foundation of circuit analysis and help us predict and control electrical behavior.

Voltage: The Electrical Pressure

Voltage represents the electrical potential difference between two points. Think of it as electrical pressure or the force that drives electrons through a circuit. When we measure voltage, we are quantifying how much energy each electron carries as it moves from one point to another. A battery marked as providing 9 volts means that electrons moving from its negative terminal to its positive terminal will each release a specific amount of energy as they complete this journey.

The water analogy proves useful here again. Voltage corresponds to water pressure in a plumbing system. Just as higher water pressure pushes water through pipes more forcefully, higher voltage pushes electrons through conductors with greater force. A AAA battery providing 1.5 volts exerts much less electrical pressure than the 120 volts coming from a household wall outlet, which explains why one is safe to handle while the other can be lethal.

Current: The Flow Rate

Current measures the rate at which electrical charge flows past a given point. We quantify current in amperes, commonly shortened to amps. One ampere represents approximately 6.24 billion billion electrons flowing past a point each second. This enormous number highlights just how incredibly tiny individual electrons are and how many of them must move together to create measurable electrical effects.

Returning to our water analogy, current corresponds to the flow rate of water through a pipe, measured in gallons per minute. A thin trickle and a rushing stream both involve water flowing, but they represent vastly different flow rates. Similarly, a small LED night light might draw 0.01 amps while an electric heater could demand 10 amps or more. Both involve electricity flowing, but the quantity of electrons moving per second differs dramatically.

Resistance: Opposition to Flow

Resistance quantifies how much a material opposes the flow of electrical current. Every conductor, even excellent ones like copper, impedes electron movement to some degree. We measure resistance in ohms, named after German physicist Georg Ohm who discovered the mathematical relationship between voltage, current, and resistance.

In our water system analogy, resistance corresponds to friction within pipes or obstacles that impede water flow. A wide, smooth pipe offers little resistance to water, allowing it to flow easily. A narrow pipe with rough interior walls creates more resistance, restricting flow even under the same pressure. Similarly, a thick copper wire presents low resistance to electrons, while a thin wire of the same material offers more resistance because electrons have fewer paths available to travel through.

Materials vary enormously in their resistance. Conductors like copper have very low resistance, which is why we use them for wiring. Insulators have essentially infinite resistance, blocking electron flow almost completely. Semiconductors can have their resistance adjusted across a wide range, which makes them invaluable for controlling and manipulating electrical signals in sophisticated ways.

How Electricity Flows: The Circuit Concept

Electricity requires a complete path to flow continuously, and this path is what we call an electrical circuit. Understanding circuits is absolutely essential for working with electronics, as every electronic device operates through carefully designed circuits that direct electricity to perform specific functions.

The Complete Path Principle

A fundamental principle governs all electrical circuits: electrons must have a complete path from the negative terminal of the power source, through the circuit components, and back to the positive terminal. This circular journey is why we use the term circuit, derived from the Latin word for circle. If we break this path at any point, the circuit becomes incomplete, called an open circuit, and current stops flowing immediately.

This principle explains why a light switch works. When you flip the switch to the off position, you physically break the circuit path, stopping electron flow and turning off the light. Flip the switch back on, and you restore the complete path, allowing electrons to flow again and illuminating the bulb. The light bulb itself does not store electricity. It simply provides a resistance that glows when current flows through it, converting electrical energy into light and heat.

Direct Current Versus Alternating Current

Electricity can flow through circuits in two fundamentally different patterns. Direct current, abbreviated as DC, involves electrons flowing continuously in one direction from the negative terminal to the positive terminal. Batteries produce direct current, with electrons consistently moving from the negative terminal through your device and back to the positive terminal. This steady, unidirectional flow makes DC ideal for electronic devices that require stable, predictable power.

Alternating current, known as AC, involves electrons that reverse direction periodically, flowing back and forth rather than moving steadily in one direction. The electricity from wall outlets uses alternating current, typically reversing direction 50 or 60 times per second depending on your country. This frequency, measured in hertz, determines how rapidly the current alternates. While this might seem inefficient compared to the steady flow of direct current, alternating current has crucial advantages for power distribution over long distances and for certain types of motors and devices.

Most electronic devices actually require direct current to function, which is why phone chargers, laptop power adapters, and other power supplies contain conversion circuits that transform the alternating current from your wall outlet into the direct current your devices need. This conversion process is so common that many people never realize their devices are not using the same type of electricity that arrives at their home.

Electrical Energy and Power

Beyond simply flowing through circuits, electricity carries energy that can be converted into other useful forms. This energy conversion is what makes electricity so valuable. When current flows through your phone charger, electrical energy converts into chemical energy stored in your battery. When you turn on a fan, electrical energy becomes mechanical motion. Understanding power helps us quantify how quickly electrical energy is being used or transformed.

Power: The Rate of Energy Transfer

Power measures how quickly electrical energy is being consumed or converted. We express power in watts, with one watt representing one joule of energy transferred per second. A 60-watt light bulb converts 60 joules of electrical energy into light and heat every second it remains on. A 1500-watt space heater consumes electrical energy 25 times faster than that bulb, which explains why running a heater significantly impacts your electricity bill compared to leaving a light on.

The mathematical relationship between power, voltage, and current reveals an important insight: power equals voltage multiplied by current. This relationship, expressed as watts equals volts times amps, shows us that we can achieve the same power level through different combinations of voltage and current. A 120-watt device might draw 1 amp at 120 volts, or it might draw 10 amps at 12 volts. Both scenarios deliver the same power, though the electrical characteristics differ considerably.

This relationship between voltage and current for delivering power has enormous practical implications. Power companies transmit electricity over long distances at very high voltages and relatively low currents because this combination minimizes energy lost to resistance in the transmission lines. When electricity reaches your neighborhood, transformers convert it to lower voltage and higher current, which is safer for household use and better suited to typical appliance requirements.

Sources of Electricity

Electricity does not generate itself. We must convert other forms of energy into electrical energy, and various methods have been developed to accomplish this conversion. Each method has advantages and limitations that make it suitable for different applications.

Chemical Energy: Batteries and Cells

Batteries store energy chemically and convert it to electricity through electrochemical reactions. Inside every battery, two different materials called electrodes sit in a chemical solution or paste called an electrolyte. Chemical reactions at these electrodes create a surplus of electrons at the negative terminal and a deficit at the positive terminal. This imbalance creates the voltage that drives current when we connect a circuit between the terminals.

Different battery chemistries produce different voltages and have different characteristics. A standard alkaline AA battery provides 1.5 volts when fresh, while a lithium-ion cell in your laptop produces around 3.7 volts. Some batteries are designed for single use, with their chemical reactions being irreversible. Others, like the lithium-ion batteries in phones and laptops, use reversible reactions that allow them to be recharged by forcing current through them in the reverse direction, restoring the chemical energy that was depleted during discharge.

Mechanical Energy: Generators

Large-scale electricity generation typically relies on converting mechanical motion into electricity using electromagnetic induction, a phenomenon discovered by Michael Faraday in 1831. When a conductor moves through a magnetic field, or when a magnetic field moves past a conductor, a voltage appears across the conductor. This principle underlies virtually all large power plants, whether they burn coal, harness falling water, capture wind, or use nuclear reactions to generate heat.

In each case, the energy source ultimately spins a generator consisting of wire coils rotating within strong magnetic fields. As these coils spin, the changing magnetic field induces voltage in the wires, creating the alternating current that flows through power grids to homes and businesses. The massive generators in power plants can produce hundreds of megawatts of electrical power, enough to supply thousands of homes simultaneously.

Solar Energy: Photovoltaic Conversion

Solar panels use an entirely different approach, converting light energy directly into electricity through the photovoltaic effect. When photons from sunlight strike certain semiconductor materials, they can knock electrons loose, creating free charge carriers that can be directed to flow as current. Modern solar panels consist of many individual photovoltaic cells connected together to produce useful voltages and currents.

Unlike generators that produce alternating current naturally, solar panels generate direct current. Systems that connect solar panels to the electrical grid require inverters that convert this direct current into alternating current matching the grid specifications. Solar technology demonstrates how understanding electrical principles allows us to harness energy from diverse sources and convert it into the standardized electrical form that powers modern technology.

Safety and Respect for Electricity

While electricity is essential and generally safe when properly contained and controlled, it demands respect and caution. The same properties that make electricity useful for powering devices can make it dangerous when mishandled. Understanding basic electrical safety protects you as you learn about and work with electronic circuits.

The danger of electricity comes primarily from current flowing through your body, which can interfere with the electrical signals your nervous system uses to control muscles, including your heart. Even relatively small currents measured in milliamps can be fatal if they pass through vital organs. Voltage determines whether current can penetrate your skin’s natural resistance, which is why the 120 or 240 volts from household outlets is far more dangerous than the 5 volts from a USB charger, even though both can deliver harmful currents under the right conditions.

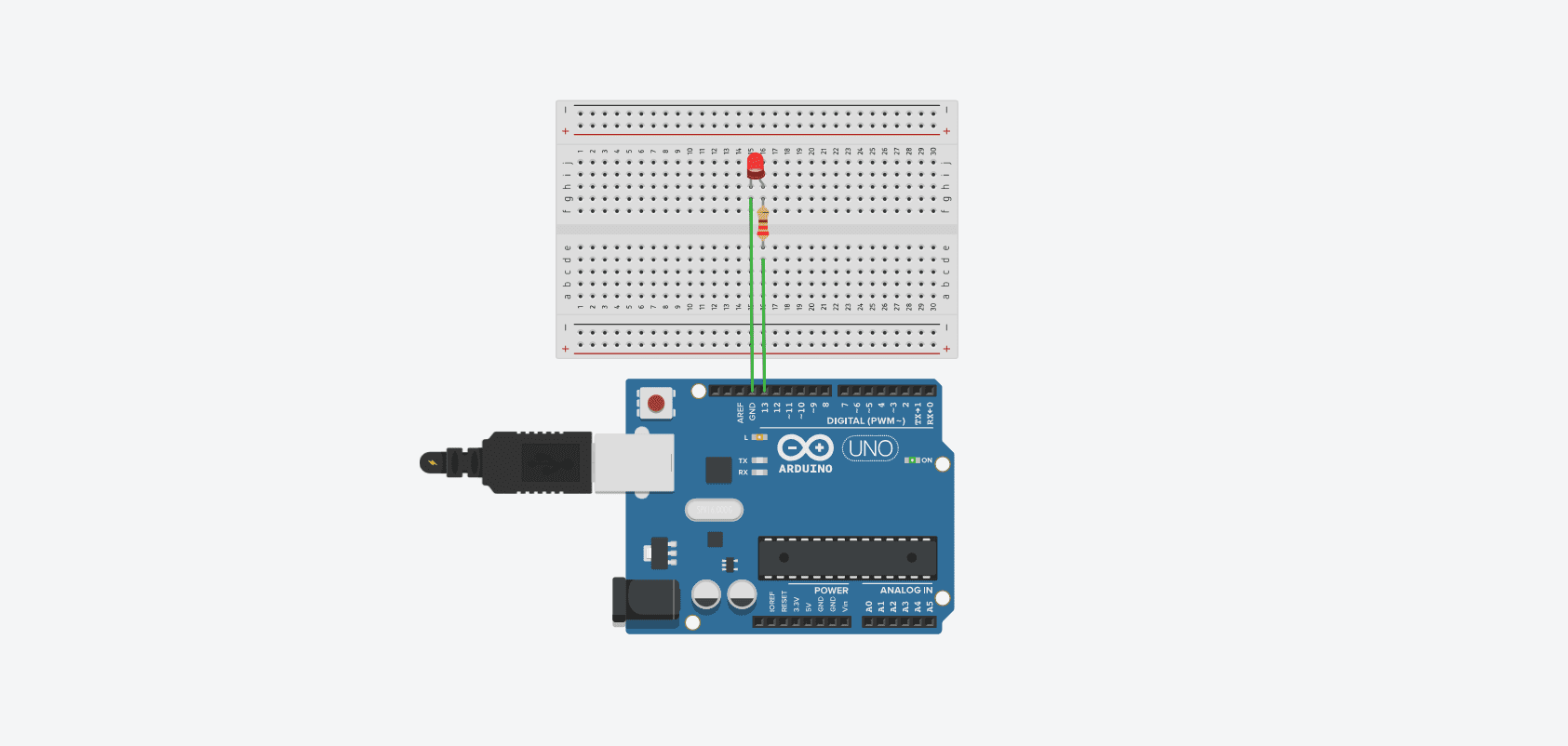

When starting your electronics journey, work with low voltages initially, typically those provided by batteries rated at 12 volts or less. These voltages cannot overcome your skin’s resistance under normal conditions and are safe to touch directly. As you gain experience and knowledge, you can gradually work with higher voltages, always following proper safety protocols including ensuring circuits are unpowered before touching components, using insulated tools, and never working on household electrical systems without proper training and qualifications.

Conclusion: Your Foundation for Electronics

Electricity is fundamentally the flow of electrons through conductors, driven by voltage and opposed by resistance. These moving charges carry energy that can be converted into light, heat, motion, or processed as information. Understanding this invisible force requires grasping several key concepts: the atomic structure that makes electron flow possible, the difference between conductors and insulators, the relationship between voltage and current and resistance, and the necessity of complete circuits for continuous flow.

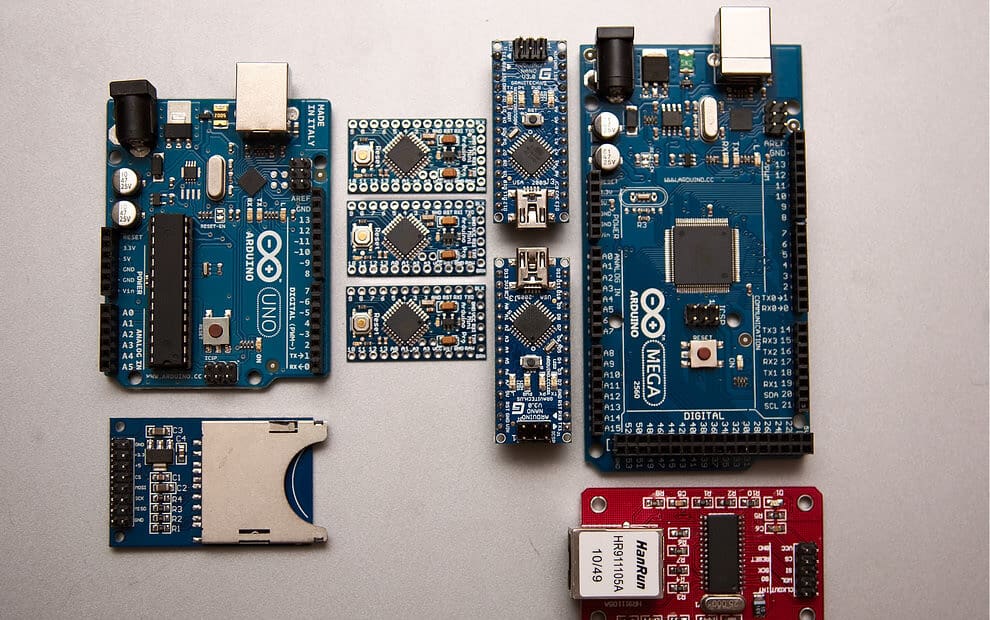

This understanding forms your foundation for everything that follows in electronics. Whether you want to build simple LED circuits, program microcontrollers, design power supplies, or create sophisticated electronic systems, you will constantly return to these fundamental principles. Every component you encounter, every circuit you analyze, and every project you build ultimately relies on controlling and manipulating the flow of electrons according to these basic rules.

As you continue your electronics journey, you will encounter these concepts repeatedly in different contexts, each time deepening your understanding and revealing new layers of complexity and possibility. The beauty of electricity lies in how such simple fundamental principles combine to enable the incredible complexity of modern technology, from smartphones containing billions of transistors to power grids spanning continents. With this foundation established, you are ready to explore the specific components, circuits, and techniques that transform electrical principles into practical applications.