Introduction: The Foundation That Everything Else Depends On

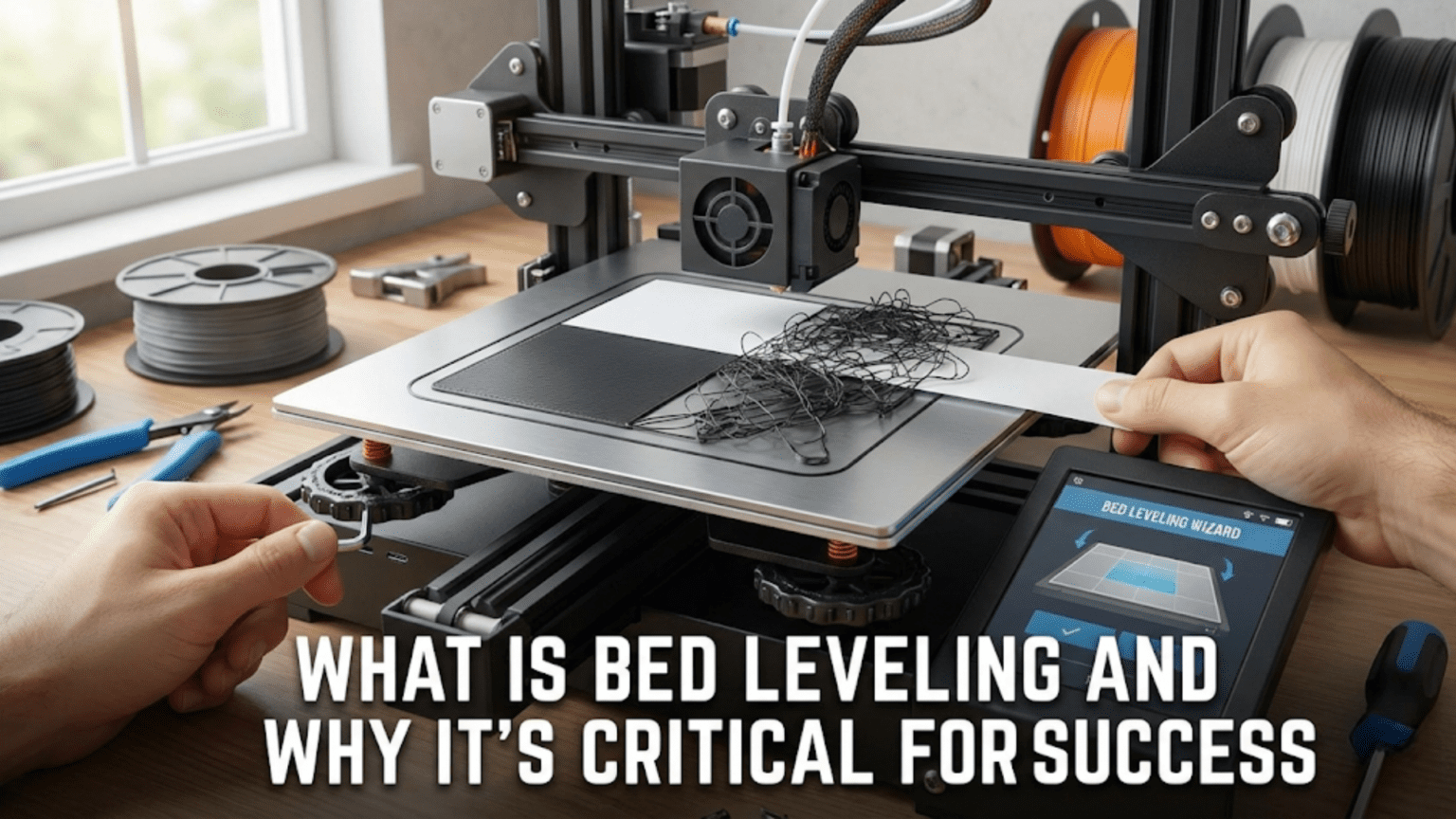

If you ask experienced 3D printer users to name the single most important factor for successful prints, many will immediately answer “bed leveling.” This might seem surprising at first because bed leveling sounds like a simple setup task rather than a critical skill. Yet the truth is that proper bed leveling forms the absolute foundation upon which every other aspect of successful printing builds. A perfectly leveled bed enables the first layer to adhere properly, which in turn determines whether the entire print succeeds or fails. No amount of optimal temperature settings, perfect retraction tuning, or ideal cooling configuration can compensate for a poorly leveled bed.

The term “bed leveling” is actually somewhat misleading because what you’re really doing isn’t making the bed level with respect to gravity. Instead, you’re ensuring the bed is parallel to the plane of motion of the print head, or more precisely, you’re adjusting the bed’s position so that the distance between the nozzle and the bed surface is consistent across the entire printing area. If the bed is perfectly parallel to the XY motion plane of the printer but sitting at a slight angle relative to the Earth’s gravitational field, that’s completely fine. The printer doesn’t care about gravity, it cares about the nozzle-to-bed distance remaining constant as the print head moves around during the crucial first layer.

This distance consistency matters because the first layer of every print must be squished down onto the bed with just the right amount of force. Too far away and the plastic doesn’t stick properly, leading to prints that lift, shift, or fall off the bed entirely during printing. Too close and the nozzle actually scrapes against the bed or the plastic has nowhere to go, causing the extruder to skip steps or grind filament as it tries to push plastic through an impossibly small gap. The ideal distance is a precise sweet spot that allows plastic to be gently compressed against the bed surface, spreading out slightly to maximize contact area and adhesion while still flowing freely from the nozzle.

The challenge is that achieving this perfect distance at one point on the bed doesn’t automatically mean it’s correct everywhere. If the bed is tilted even slightly, perhaps higher on one side than the other, the nozzle distance will be perfect in some areas but too far or too close in others. A print that starts in the correctly-adjusted area might work fine, while the same print positioned differently on the bed fails because that area has incorrect nozzle distance. This is why bed leveling involves adjusting multiple points, typically three or four corners of the bed, to ensure the entire surface is at the correct distance from the nozzle’s path.

The reason bed leveling requires ongoing attention rather than being a one-time setup is that beds can shift slightly over time. Every time you remove a finished print, you might inadvertently apply force that shifts the bed’s position microscopically. Temperature changes as the bed heats and cools can cause mechanical components to expand and contract, potentially affecting alignment. Vibration during printing can gradually work adjustment screws loose. The printer being moved or jostled can throw off careful leveling. For these reasons, experienced users typically check and adjust bed leveling regularly, perhaps before every print or at least every few prints, rather than assuming it remains perfect indefinitely.

Understanding bed leveling deeply helps demystify one of the most common sources of print failures for beginners. When you know what bed leveling actually accomplishes, why it matters, how to do it correctly, and how to recognize and fix leveling problems, you transform bed leveling from a frustrating mystery into a manageable maintenance task. You’ll spend less time watching first layers fail and more time producing successful prints because your foundation is solid. This article explores bed leveling comprehensively, covering both manual leveling techniques and automatic bed leveling systems, explaining the physics and geometry involved, and providing strategies for achieving and maintaining proper leveling.

The Physics and Geometry of the First Layer

To truly understand why bed leveling matters so much, you need to appreciate what happens during that critical first layer and how the geometric relationship between nozzle and bed determines whether the layer succeeds or fails. Let’s examine the physics involved in creating a good first layer and see why precise distance control is so essential.

When your printer begins a print, the nozzle descends toward the bed until it reaches the Z height defined for the first layer, typically around two tenths of a millimeter. This measurement represents the intended gap between the nozzle tip and the bed surface. Molten plastic emerges from the nozzle at this height and must cross this tiny gap before contacting the bed. In that moment of contact, several things need to happen simultaneously for success.

First, the hot plastic must spread out laterally as it’s compressed between the descending nozzle and the stationary bed. This spreading increases the contact area between plastic and bed, improving adhesion. The amount of spreading depends on the gap height. If the gap is slightly smaller than the extrusion width your slicer calculated, the plastic gets compressed and spreads nicely. If the gap is too large, the plastic doesn’t compress and the contact area remains minimal, creating weak adhesion.

Second, the plastic must maintain enough heat to bond with the bed surface while beginning to cool and solidify. The bed temperature helps keep the plastic workable, but the plastic is also cooling from contact with air. The time the plastic spends in contact with the warm bed before the nozzle moves on affects bonding. If the nozzle is too far away, the plastic might cool too much before adequate bonding occurs. If the nozzle is too close, it might actually drag through the not-yet-solid plastic, creating a mess.

Third, the extruded line must have structural integrity to support the second layer that will eventually be deposited on top of it. If the first layer is too thin because the nozzle is too close, the line might be so compressed that it’s thinner than intended, potentially creating weak spots. If the first layer is too thick because the nozzle is too far, the plastic pile might be unstable or poorly bonded.

The ideal first layer height represents a compromise between these various requirements. Most users find that setting first layer height to be slightly larger than their normal layer height works well, perhaps one hundred twenty to one hundred fifty percent of the standard layer height. This gives a bit more margin for error and helps ensure good squish against the bed. However, this ideal works only if the actual nozzle-to-bed distance matches what the printer thinks it is.

This is where bed leveling enters the picture. The printer’s firmware maintains a coordinate system where Z equals zero represents the nozzle touching the bed. When you command the printer to move to Z equals zero point two millimeters for the first layer, the firmware believes it’s positioning the nozzle two tenths of a millimeter above the bed. But if your bed is actually tilted, some areas might be at the correct height while others are too high or too low. The printer doesn’t know the bed is tilted, it faithfully positions the nozzle at what it believes is the correct Z height, unaware that the bed surface isn’t where it should be.

Consider a bed that’s tilted so the left side is one tenth of a millimeter higher than the right side. When printing on the left side with the first layer set to two tenths of a millimeter, the actual gap is only one tenth of a millimeter because the bed surface is higher than expected. The plastic gets over-compressed, potentially causing the nozzle to scrape the bed or creating excessive spreading that produces elephant’s foot where the bottom of the print is wider than intended. Meanwhile, printing on the right side with that same Z height setting gives an actual gap of three tenths of a millimeter because the bed is lower than expected. The plastic doesn’t compress adequately, adhesion is poor, and the first layer might not stick at all.

The geometry involved means that even tiny bed misalignments create significant problems. A tilt of just one or two tenths of a millimeter across a twenty-centimeter bed width might not sound like much, but when your target first layer height is only two or three tenths of a millimeter, that tilt represents a fifty to one hundred percent variation in the actual gap from one side to the other. This massive percentage variation explains why bed leveling requires such precision and why even experienced users need to check and adjust it regularly.

The three-point or four-point leveling system used by most printers reflects the geometric fact that three points define a plane. If you adjust three corners of a rectangular bed properly, the entire bed surface should lie in a plane parallel to the nozzle’s motion. Some printers use four adjustment points, one at each corner, which provides redundancy but also means the adjustments interact more complexly since you’re technically over-constraining the plane. Understanding this geometry helps you approach bed leveling systematically rather than randomly twisting knobs hoping for improvement.

Manual Bed Leveling: The Traditional Approach

Manual bed leveling, where you physically adjust the bed’s position using mechanical adjustments, remains the most common leveling method and the one every 3D printer user should understand even if their printer includes automatic leveling features. Learning to manually level a bed properly builds understanding of what proper leveling feels like and provides a reliable fallback when automatic systems misbehave or aren’t available.

The typical manual leveling system uses adjustment knobs or screws at three or four points under the bed, usually at the corners. These adjustments change the bed’s position relative to the printer’s frame, allowing you to tilt and position the bed until it’s parallel to the nozzle’s motion plane. The knobs usually thread into springs that provide compliance, allowing fine adjustments and helping the bed maintain its position against vibration and thermal expansion.

The standard manual leveling procedure begins with homing all axes so the printer knows its position, then moving the nozzle to the first leveling point, typically one corner of the bed. With the nozzle positioned at your target first layer height above where the bed should be, you slide a thin piece of paper between the nozzle and bed as a feeler gauge. The paper should drag slightly when you pull it but not be so tight that it tears or prevents movement. This light drag indicates the nozzle is just barely touching the paper, providing a consistent reference for the correct distance.

The paper drag method works because a typical piece of printer paper is approximately one tenth of a millimeter thick. When you feel proper drag with the paper between nozzle and bed, you know the gap is roughly one tenth of a millimeter. This is slightly closer than your actual first layer height will be, but it provides a consistent reference point. During actual printing, the nozzle will be slightly higher than the paper-drag position, creating the intended first layer gap.

Starting at the first corner, you adjust that corner’s leveling knob until you feel appropriate paper drag. Then you move to the next corner, repeat the adjustment, and continue until all corners are adjusted. Here’s where the interactive nature of leveling becomes apparent because adjusting one corner affects the others. When you tighten a knob raising that corner, the bed pivots slightly and other corners drop relative to the nozzle. This means you can’t simply adjust each corner once and be done. Instead, you need to work in cycles, adjusting all corners in sequence multiple times until all positions show consistent paper drag.

Many experienced users develop a feel for how adjustment directions affect other corners. On a typical three-point leveling system, adjusting the two back corners primarily affects the front-to-back tilt, while the front corner fine-tunes the side-to-side balance. On four-point systems, opposite corners interact strongly so adjustments often involve tuning opposite pairs together. Understanding these interactions helps you converge on good leveling faster rather than chasing your tail as adjustments at one corner undo previous adjustments at others.

The center of the bed deserves attention during leveling because some beds sag or bow slightly in the middle despite having corners adjusted correctly. After getting all corners leveled, move the nozzle to the bed’s center and check paper drag. If the center is significantly higher or lower than the corners, the bed itself isn’t perfectly flat. Small variations, perhaps within one or two tenths of a millimeter, are acceptable, but larger bows indicate bed quality issues that leveling adjustments alone can’t fix.

Temperature affects bed leveling because thermal expansion changes dimensions as components heat up. An ideally leveled cold bed might develop slight tilts when heated to printing temperature as the bed, bed support structure, and frame all expand at potentially different rates. For best results, perform bed leveling with the bed heated to your typical printing temperature. This ensures the geometry you’re setting up matches what will exist during actual printing rather than the cold state.

Some printers include mesh bed leveling, a semi-manual process where you manually level at multiple points across the bed while the printer records the height at each point. The firmware then creates a mesh representing the bed’s surface and compensates for variations during printing by adjusting Z height as the nozzle moves around. This bridges the gap between pure manual leveling and automatic probing by allowing you to characterize bed irregularities without needing probe hardware.

The frequency of manual leveling depends on your printer and usage patterns. Some users level before every print, taking five minutes to ensure everything is perfect. Others level weekly or even monthly, relying on stability of their setup and checking the first layer visually during prints to catch problems early. If you notice first layer adhesion problems appearing gradually, that often signals it’s time for a releveling session.

Automatic Bed Leveling: Technology to the Rescue

Automatic bed leveling, often abbreviated as ABL, uses a probe or sensor to measure the bed’s position at multiple points and automatically compensates for any tilt or irregularities. This technology has become increasingly common on 3D printers at all price points because it eliminates the tedious manual leveling process and can compensate for bed imperfections that manual leveling alone cannot address. Understanding how automatic bed leveling works and how to use it effectively helps you leverage this feature if your printer has it.

The core concept behind automatic bed leveling involves the printer probing the bed at multiple locations, measuring the actual Z height at each point, and building a model of the bed’s surface. During printing, the firmware references this model and adjusts Z height dynamically as the nozzle moves around, keeping the nozzle at the correct distance from the bed surface even if that surface isn’t perfectly flat or parallel to the XY motion plane. This compensation happens continuously and transparently during printing, with the Z axis making tiny adjustments that you probably won’t even notice.

Several probe technologies enable automatic bed leveling. Inductive probes detect the presence of metal, working well with metal build surfaces or beds with metal backing. These probes are non-contact, meaning they trigger when near metal rather than requiring physical contact. The advantage is no mechanical wear and reliable consistent triggering. The disadvantage is they only work with conductive surfaces and sometimes have temperature sensitivity affecting accuracy.

Capacitive probes detect changes in capacitance near conductive or non-conductive surfaces, making them more versatile than inductive probes. They work with glass beds, PEI sheets, metal surfaces, and most other common build surfaces. Like inductive probes, they’re non-contact and don’t suffer mechanical wear. However, they can be finicky about mounting and sometimes sensitive to environmental factors like humidity.

BLTouch and similar mechanical touch probes use a small probe pin that physically contacts the bed surface. When the probe touches the bed, it triggers a signal telling the firmware the bed position. These probes are popular because they work with any bed surface, provide reliable consistent measurements, and are relatively easy to configure. The mechanical nature means they may eventually wear out, though typically after thousands of probing cycles.

Nozzle-based probing eliminates a separate probe entirely by using the nozzle itself as the probe. Some printers use strain gauges or force sensors that detect when the nozzle contacts the bed, while others use the nozzle continuity method where completing an electrical circuit between nozzle and bed indicates contact. Nozzle probing has the advantage that the nozzle is exactly where printing happens, eliminating probe offset calibration. The disadvantage is requiring the nozzle to physically touch the bed, potentially leaving marks or requiring the bed to be electrically conductive for continuity-based systems.

The automatic bed leveling process typically involves commanding the printer to run its bed leveling routine, whereupon the probe visits a predefined grid of points across the bed surface. At each point, the probe measures the Z height, and the firmware records this measurement. After probing all points, the firmware constructs a mesh representing the bed’s surface topology. This mesh might be as simple as a three-point plane fit or as complex as a detailed grid with dozens of probe points capturing subtle bed variations.

The number of probe points represents a trade-off between accuracy and time. More probe points capture bed irregularities in greater detail, allowing more accurate compensation. However, each probe point takes time, perhaps five to ten seconds, and large probe grids can extend the pre-print setup significantly. Most users find that a seven-by-seven or nine-by-nine grid provides good accuracy without excessive time investment, though smaller prints might work fine with coarser grids.

Probe offset calibration is crucial for accurate automatic bed leveling. The probe sensor is physically offset from the nozzle tip, typically by several millimeters or centimeters in X and Y and sometimes by a small amount in Z. The firmware needs to know these offsets precisely to correctly translate probe measurements into nozzle positions. Most printers require you to measure and configure these offsets during initial setup. Getting offsets wrong means the compensation applies at incorrect locations, potentially making bed leveling worse rather than better.

Z offset represents another critical parameter, defining how far the nozzle should be from the bed when the probe triggers. Even with perfectly measured XY offsets and an accurate bed mesh, if Z offset is wrong, your nozzle will be too high or too low during printing. Z offset adjustment is often called “baby stepping” and many printers allow real-time adjustment during the first layer so you can dial in the perfect squish while watching the first layer go down.

Automatic bed leveling doesn’t eliminate the need for mechanical bed adjustments entirely. The ABL system has compensation limits, typically only able to correct for a millimeter or two of tilt or irregularity. If your bed is severely tilted, perhaps several millimeters off at one corner, automatic leveling might not be able to fully compensate and you’ll need to manually adjust leveling knobs to get the bed roughly level before relying on automatic compensation for fine details. Think of automatic bed leveling as fine-tuning rather than wholesale correction.

The mesh created by automatic bed leveling often persists in the printer’s memory across power cycles, meaning you don’t necessarily need to probe before every print. However, meshes should be refreshed periodically, perhaps weekly or monthly, to account for any bed changes over time. Some users probe before every print for maximum confidence, while others trust their saved mesh until they notice first layer problems reappearing.

Recognizing and Diagnosing Bed Leveling Problems

Learning to recognize the characteristic symptoms of bed leveling problems helps you quickly identify when leveling needs attention rather than pursuing red herrings or wasting time troubleshooting unrelated issues. Different leveling problems create distinct signatures in first layer appearance and print behavior. Let’s examine these signatures and learn to interpret them.

The clearest indicator of bed leveling issues appears in first layer adhesion quality across different areas of the bed. If one corner or side of the bed consistently shows poor first layer adhesion while other areas stick well, the bed is almost certainly not level. The area with poor adhesion is either too high, causing the nozzle to be too far away for good squish, or too low, causing the nozzle to be too close and creating other problems.

Visual inspection of first layer extrusion reveals specific leveling problems through characteristic patterns. When the nozzle is too close, the extruded lines appear thinner than they should be because excess compression squishes the plastic into the bed. In extreme cases, the lines might show transparent or translucent sections where plastic has been compressed so thin you can almost see through it. The bed surface might show scratching or scraping marks where the nozzle actually contacted it. You might hear clicking or grinding from the extruder as it tries to push plastic through an impossibly small gap.

When the nozzle is too far away, the extruded lines appear tall and rounded rather than flat and wide. The lines might not stick to the bed at all, either not adhering initially or peeling up after deposition. You might see gaps between individual lines of the first layer because the plastic isn’t spreading enough to overlap adjacent lines. In severe cases, the plastic doesn’t stick and just gets dragged around by the moving nozzle, creating a bird’s nest or spaghetti pile rather than a first layer.

The perfectly leveled first layer shows extruded lines that are slightly wider than the nozzle diameter, appearing flat against the bed with slight transparency where compressed but not so thin as to be weak. The lines have good contact with the bed surface and with each other, creating a solid continuous sheet. The first layer should have a smooth, matte finish rather than glossy or textured appearance.

Regional variations in first layer appearance indicate specific leveling problems. If the left side looks perfectly squished but the right side shows poor adhesion, the bed is higher on the left than the right. If corners look good but the center shows problems, the bed might be bowed. If one back corner is bad while everything else is fine, that specific corner needs adjustment. Reading these regional differences tells you exactly where to focus your leveling adjustments.

The infamous “first layer not sticking” problem that plagues beginners is often bed leveling in disguise. Before assuming you have adhesion, temperature, or material issues, verify leveling first. A properly leveled bed with appropriate temperature and clean surface should stick pretty much anything. If it doesn’t, leveling is the most likely culprit. Only after confirming good leveling should you investigate other adhesion factors.

The first layer skirt or brim provides valuable diagnostic information about leveling. Many slicers automatically add a skirt, a line or two printed around the perimeter of the print before the actual object begins. Watching this skirt go down shows you immediately whether adhesion is working. If the skirt peels up, doesn’t stick, or looks wrong in some areas, stop the print right then and fix leveling rather than continuing and wasting filament on a print destined to fail.

Elephant’s foot, where the very bottom of your print is wider than it should be and bulges outward, often indicates the nozzle is slightly too close on the first few layers. The excess squish spreads plastic laterally beyond the intended boundaries. While this isn’t always a leveling issue, it can be if the nozzle is only too close because the bed is higher than the printer thinks. Raising the Z offset or lowering that area of the bed slightly can eliminate elephant’s foot.

Inconsistent behavior where prints sometimes stick and sometimes don’t, seemingly randomly, can indicate marginal leveling that’s right at the edge of working. Slight variations in filament diameter, temperature, or even ambient humidity tip the balance one direction or another. This inconsistency is maddening but often resolves completely with better leveling that provides more margin for error.

Multi-material or multi-color prints with tool changes can reveal leveling problems that don’t show up in single-material prints. Each tool might have slightly different geometry or probe offset, meaning bed leveling that works for one tool fails for another. This situation requires individual Z offset adjustment for each tool or very precise mechanical alignment of all tools.

Temperature-dependent leveling issues appear when prints that work fine at one bed temperature fail at different temperatures. Thermal expansion changes bed geometry, so leveling that’s perfect at sixty degrees might be off at eighty degrees. The solution involves leveling at your most common bed temperature or re-leveling when switching between significantly different temperatures.

Advanced Leveling Techniques and Troubleshooting

Beyond basic leveling procedures, several advanced techniques and considerations help you achieve even better results or address challenging leveling situations. Understanding these approaches expands your toolbox for handling unusual cases or pushing leveling precision to its limits.

Mesh bed leveling visualization helps you understand what’s actually happening with your bed’s surface. Many printer control interfaces can display the bed mesh graphically, showing which areas are high or low relative to the average. This visualization immediately reveals patterns like corner sag, center bowing, or systematic tilts that might not be obvious from manual probing. If your printer supports mesh visualization, spending time studying it can guide mechanical adjustments that improve the base bed flatness before compensation even starts.

Some beds are simply not flat, bowing upward or sagging downward in the center or developing waves across their surface. Glass beds can bow, aluminum beds can warp from stress or temperature, magnetic flex plates can have thickness variations, and build surfaces themselves can develop irregularities. When the bed itself isn’t flat, even perfect leveling of the corners won’t produce a perfectly leveled bed. Automatic bed leveling with a dense mesh compensates for these issues during printing, but if your bed has severe flatness problems, replacing it or using a surface with better flatness might be necessary.

Some users add shimming under problematic bed areas to mechanically flatten the bed before leveling. Thin shims made from aluminum foil, paper, or Kapton tape can fill in low spots or counteract bowing. This is somewhat trial-and-error since you need to determine where shimming should go and how thick it should be, but it can transform an unlevelable bed into a manageable one. The goal is getting the bed close enough to flat that automatic leveling or careful manual leveling can handle the remaining irregularities.

Tilt-based bed support designs that allow adjusting the bed’s tilt directly rather than through corner screws can simplify leveling. Some printers use kinematic mounts with precise tilt adjustments, making the bed inherently more stable and adjustable. Upgrading to better bed mounting hardware can be worthwhile if you struggle with leveling stability on a printer with basic mounting.

Exaggerated first layers intentionally print the first layer thicker than normal to provide more margin for minor leveling imperfections. Using a first layer height of one hundred fifty to two hundred percent of normal layer height gives you more tolerance. The trade-off is a more pronounced first layer line appearance on the bottom of prints, but for functional parts this is usually acceptable and the improved reliability is worth it.

Live Z adjustment during the first layer allows correcting leveling on the fly as you watch the first layer go down. Many printers support baby stepping, adjusting Z offset in real time while the print is running. If you start a print and see the first layer isn’t quite right, you can adjust Z offset up or down by small increments until it looks perfect, then save that offset for future prints. This dynamic adjustment is incredibly valuable for dialing in the exact perfect squish without multiple test prints.

Test patterns specifically designed for leveling verification help assess leveling quality objectively. Single-layer test patterns that print squares or lines across the entire bed surface show you immediately which areas are good and which need work. These patterns complete in just a minute or two, making them much faster than full prints for iterating on leveling adjustments. Many online repositories offer downloadable leveling test patterns.

The bed surface condition affects apparent leveling because adhesion varies with surface cleanliness and preparation. An area of the bed with fingerprint oils or release agent residue might not stick even with perfect leveling, creating the false impression that area is too high. Always ensure your bed is clean before attributing adhesion problems to leveling. A quick wipe with isopropyl alcohol removes most contaminants and is good practice before every print.

Different build surfaces have different optimal Z offsets because they have different thicknesses and surface properties. If you use multiple build surfaces, swapping between them, each might need its own Z offset value. Some printers allow saving different profiles for different surfaces, automatically loading the correct offset when you indicate which surface you’re using. This prevents having to re-level every time you change surfaces.

Gantry and motion system squareness affects leveling in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. If the X gantry isn’t perfectly square to the Z axis, or if the frame itself is slightly racked, no amount of bed leveling can fully compensate. These fundamental mechanical alignment issues create situations where leveling seems impossible or requires absurd adjustments. Before assuming your bed is hopelessly bad, verify that the printer’s frame and motion systems are properly aligned and square.

Warped or twisted frames cause leveling problems that persist despite your best efforts. If your printer was assembled incorrectly, dropped, or has structural damage, the frame geometry might be off enough that proper leveling becomes impossible. This is rare but worth checking if you’ve exhausted other troubleshooting. A machinist’s square or carpenter’s framing square can help verify that major frame elements are square to each other.

Automatic probe accuracy limitations mean even the best ABL systems have error margins, typically around plus or minus one tenth of a millimeter or so. This is usually good enough for successful printing, but if you need extreme precision, understanding these limits helps set realistic expectations. No system is perfect, and accepting that occasional minor leveling artifacts might appear even with perfect setup prevents frustration.

Bed Surfaces and Their Impact on Leveling

The build surface you use interacts significantly with bed leveling because different surfaces have different characteristics affecting adhesion, thickness, and temperature tolerance. Understanding how various surfaces interact with leveling helps you choose appropriate surfaces and adjust leveling for each one.

Glass beds provide excellent flatness and rigidity, potentially improving leveling by starting with a truly flat surface. Glass doesn’t warp or bow like some other materials and is easy to clean. However, glass requires precise leveling because it offers less room for error than textured surfaces. The perfectly smooth surface means adhesion is highly sensitive to nozzle distance, with even slight over or under spacing creating problems. Glass also requires higher bed temperatures for equivalent adhesion compared to textured surfaces.

PEI build surfaces, whether rigid sheets or flexible magnetic-backed, provide excellent adhesion and forgive minor leveling imperfections better than glass. The slightly textured surface grabs plastic more aggressively, giving wider margins for acceptable nozzle distance. PEI maintains good adhesion across reasonable first layer height variations, making it beginner-friendly. The flexible varieties can be removed to pop off finished prints, though this repeated flexing can potentially affect leveling over time.

Textured powder-coated surfaces offer similar benefits to PEI with even more aggressive texture that provides strong adhesion. These surfaces are very forgiving of leveling variations, often sticking well even if nozzle distance is slightly off. The disadvantage is that the texture transfers to the bottom of prints, which is desirable for some applications but problematic if you need smooth first layers. The magnetic backing in removable textured surfaces adds thickness that affects Z offset.

Blue painter’s tape applied to the bed surface provides good adhesion for PLA and is cheap and replaceable. However, tape application needs to be smooth without bubbles or wrinkles, and achieving even thickness across the entire bed can be challenging. Any thickness variation from tape overlap or uneven application effectively creates bed irregularities that leveling can’t fix. Despite this, many users successfully print on tape by carefully applying it flat and smooth.

Glue sticks and adhesion promoters applied to bed surfaces help with stick but can create thickness variations if applied unevenly. These shouldn’t be necessary with proper leveling, but they’re often used as workarounds for marginal leveling. A properly leveled bed with clean surface should stick without chemical assistance for most common materials.

Magnetic flexible build plates consist of a magnetic base layer stuck to the bed and a flexible steel sheet with build surface that sits on top. These are popular because you can remove the flexible top sheet to release prints. However, this two-layer system introduces considerations for leveling. The magnetic attraction holds the steel sheet against the base, but if the base isn’t perfectly flat, the steel sheet conforms to those irregularities. Additionally, the magnetic field might not be uniform, creating slight thickness variations in the assembled plate.

Build surface temperature affects adhesion separate from but related to leveling. Even perfectly leveled beds won’t stick if bed temperature is too low for the material. Conversely, too high bed temperature can cause other problems. The temperature interacts with leveling because hotter surfaces provide more adhesion forgiveness for marginal leveling. This is why many troubleshooting guides suggest increasing bed temperature, it’s not fixing leveling but compensating for marginal leveling by improving adhesion.

Surface wear and degradation over time can affect both adhesion and apparent levelness. A worn area of PEI or degraded glass coating might not stick as well as fresh areas, creating the impression that area is high even if leveling is perfect. Replace or refresh worn build surfaces to maintain consistent adhesion across the entire bed.

Changing between build surfaces requires Z offset adjustment because different surface thicknesses put the actual printing surface at different heights. Going from a thin PEI sheet to a thick glass bed might require adjusting Z offset by a millimeter or more. Always recalibrate Z offset when changing surfaces unless you’re swapping identical-thickness surfaces.

Maintaining Good Leveling Long Term

Achieving good bed leveling once is valuable, but maintaining it over time without constant re-leveling represents real mastery. Several strategies and habits help keep your bed leveled longer between adjustments, reducing frustration and improving printing success rates.

Minimizing mechanical disturbance to the bed preserves leveling longer. When removing finished prints, avoid using excessive force or prying aggressively right against the bed surface. Let the bed cool if you’re using a material that releases better cold, then use scrapers or spatulas gently. Each forceful print removal can slightly shift the bed even if you don’t consciously feel it happening. Flexible build plates that you can remove and bend to release prints are valuable because they eliminate force applied directly to the bed.

Thread locking compound applied to leveling adjustment screws prevents them from vibrating loose over time. A tiny drop of removable thread locker keeps adjustments stable while still allowing future changes. This is particularly valuable if your printer vibrates significantly during printing or if adjustment knobs have repeatedly worked loose. Don’t use permanent thread locker as you’ll need to adjust these screws occasionally.

Regular visual checks during first layers catch leveling problems early before they cause failed prints. Getting in the habit of watching the first layer go down every time you start a print lets you spot developing issues immediately. If adhesion starts looking marginal in one area, you know leveling is drifting and can address it before prints start failing entirely.

Periodic re-leveling even when everything seems fine prevents gradual drift from accumulating into serious problems. Many users make leveling part of their routine, perhaps weekly or after every few prints, checking and adjusting as needed even if the previous print looked perfect. This proactive approach catches small changes before they become large problems.

Environmental stability helps maintain consistent leveling. Printers in environments with stable temperature and humidity maintain better dimensional stability than printers subjected to large swings. If your printer lives in a garage that goes from hot to cold daily or a basement with humidity variations, expect more frequent leveling needs. Enclosures help by creating more stable local environments around printers.

Structural improvements to your printer can enhance leveling stability. Upgrading to more rigid bed mounting, replacing weak springs with stiffer ones, or improving frame rigidity all help the bed maintain its adjusted position longer. These modifications require mechanical aptitude and might void warranties, but for users struggling with chronically unstable leveling, they can provide lasting improvement.

Firmware settings affecting Z position should remain constant once properly set. Accidentally changing firmware parameters related to steps per millimeter for Z axis, bed leveling mesh, or Z offset will throw off your carefully adjusted leveling. If you’re experimenting with firmware, document your working settings and be prepared to restore them if changes cause leveling problems.

Multiple bed configurations can save time if you use different surfaces or materials regularly. Some printers allow saving multiple bed leveling meshes or Z offsets for different situations. Configure and save settings for each surface or material you use, then load the appropriate configuration when printing rather than re-leveling each time you switch.

Learning your specific printer’s leveling drift patterns helps you predict when re-leveling is needed. You might notice that your printer tends to drift in one corner, or that leveling stays good for exactly ten prints before needing adjustment. This pattern recognition lets you proactively maintain leveling rather than reactively fixing it after problems appear.

Conclusion: The Unshakeable Foundation

Bed leveling stands as the fundamental prerequisite for successful 3D printing, the foundation that must be solid before anything else can work properly. No matter how precisely you’ve tuned temperatures, how perfectly you’ve calibrated extrusion, or how carefully you’ve designed your model, a poorly leveled bed will cause failures that no other optimization can overcome. Conversely, with a properly leveled bed, many other imperfections become manageable or even unnoticeable because the foundation enables the first layer to succeed.

The physics and geometry underlying bed leveling reveal why such precision is necessary. The tiny gap between nozzle and bed, measured in tenths of millimeters, represents the entire working distance for first layer deposition. Variations of even a tenth of a millimeter across that gap can mean the difference between excellent adhesion and complete failure. This sensitivity to distance demands leveling accuracy that matches or exceeds the tolerances of the first layer height itself.

Manual bed leveling techniques provide the fundamental skills every printer operator should master. Understanding the paper drag method, recognizing how adjustment points interact, and developing feel for proper leveling builds competence that remains valuable even when using printers with automatic systems. The ability to manually level a bed when automatic systems fail or when working with printers lacking such features ensures you’re never completely dependent on automation.

Automatic bed leveling systems enhance convenience and can compensate for bed imperfections impossible to fix manually, but they’re not magic solutions that eliminate the need for understanding. You must still ensure the bed is roughly level mechanically before automatic compensation engages, properly configure probe offsets and Z height, and understand the limitations of what compensation can achieve. Automatic systems assist but don’t replace fundamental understanding of what leveling accomplishes.

Recognizing leveling problems through their characteristic signatures, whether poor adhesion in specific regions, incorrect first layer appearance, or consistency issues across the bed, enables rapid diagnosis and targeted fixes. Many beginners waste hours troubleshooting adhesion, temperature, or material problems when leveling is actually the culprit. Learning to see leveling issues for what they are saves enormous time and frustration.

Advanced techniques including mesh visualization, shimming, live Z adjustment, and surface-specific calibration expand your capabilities for handling challenging situations or achieving exceptional precision. These aren’t necessary for everyone or every printer, but knowing they exist and understanding when they’re appropriate adds tools to your problem-solving arsenal.

Build surface selection and maintenance interacts with leveling in ways that affect long-term success. Understanding how different surfaces behave, maintaining surface cleanliness, and properly adjusting for surface changes ensures that leveling efforts translate into actual printing success rather than being undermined by surface issues.

Long-term leveling maintenance through careful print removal, periodic checking, structural stability, and environmental control keeps your bed properly leveled longer between major adjustments. These habits transform leveling from a constant frustration into an occasional maintenance task, freeing you to focus on designing and printing rather than constantly fighting bed adhesion.

The investment you make in truly understanding bed leveling pays dividends every time you print. The five or ten minutes spent carefully checking and adjusting leveling before printing prevents the hour or more wasted on failed prints that desticked halfway through. The deeper understanding of what leveling accomplishes and why it matters helps you diagnose problems quickly and fix them correctly rather than applying random solutions hoping something works.

Looking forward, bed leveling will remain essential even as 3D printing technology advances. While automatic systems become more capable and error-tolerant, and while new bed surfaces and adhesion technologies emerge, the fundamental requirement that the first layer must properly adhere at consistent height across the entire bed will persist. Understanding leveling principles ensures you can work effectively with current equipment and adapt to future innovations.

Bed leveling deserves respect as the single most important setup task in 3D printing. Treat it as the critical foundation it is rather than an annoying preliminary step to rush through. Take the time to level properly, check regularly, and maintain carefully. Your prints will reward this attention with consistent success, clean first layers, and far fewer mysterious failures that waste time and material. The solid foundation of a well-leveled bed supports everything else you do in 3D printing, enabling your skills and optimizations in other areas to shine through in beautiful, successful prints.