Introduction: The Foundation of Consistent 3D Printing

Imagine spending hours carefully adjusting your 3D printer settings to achieve a perfect print. The layer height is dialed in just right, the temperature produces beautiful layer adhesion without stringing, the speed balances quality with reasonable print time, and every other parameter has been fine-tuned through trial and error. Your print comes off the bed looking fantastic. Now imagine having to remember and manually re-enter all those settings the next time you want to print something similar. This tedious scenario is exactly what print profiles were designed to prevent.

A print profile is essentially a saved collection of all the settings that define how your slicer will prepare a 3D model for printing. Think of it as a recipe that captures not just the ingredients but the exact quantities, temperatures, mixing times, and cooking methods needed to recreate a successful result. Just as a chef might have different recipes for different dishes, 3D printing enthusiasts develop different profiles for different situations, materials, quality levels, and printer configurations.

The concept of print profiles might seem straightforward on the surface, but understanding how to effectively create, manage, and use profiles represents one of the most important skills in developing an efficient 3D printing workflow. Profiles aren’t just about convenience, though that’s certainly part of their value. They’re about consistency, repeatability, and building a knowledge base that grows with your experience. When you discover settings that work well for a particular material or application, capturing those settings in a profile means you’re building on your successes rather than starting from scratch each time.

Modern slicing software comes with built-in profiles for common printers and materials, and these provide excellent starting points for beginners. However, as you gain experience, you’ll find that creating custom profiles tailored to your specific equipment, materials, and requirements becomes essential for achieving the best results. Understanding what profiles contain, how they’re organized, and how to systematically develop and refine them transforms 3D printing from a frustrating process of constant adjustment into a predictable, reliable manufacturing method.

This article explores the world of print profiles in depth. We’ll examine what information profiles actually contain, understand the different types of profiles and how they interact, learn strategies for creating effective custom profiles, discover best practices for organizing and managing profile libraries, and explore advanced techniques for optimizing profiles for specific applications. By the end, you’ll have a comprehensive understanding of how profiles work and how to leverage them for consistent, high-quality printing.

What Information Does a Print Profile Actually Contain?

To understand print profiles, you first need to appreciate the sheer number of parameters that influence how a 3D print turns out. When you load a 3D model into slicing software, that software must make hundreds of decisions about how to convert the solid digital model into instructions your printer can follow. Every one of these decisions is controlled by a setting, and all these settings together comprise what gets saved in a profile.

At the most fundamental level, a print profile contains layer height information, which determines how thick each horizontal slice of your print will be. This single parameter has enormous influence over print time, surface quality, and the level of detail that can be achieved. But layer height is just the beginning. The profile also specifies the number of perimeter walls to print around the outside of each layer, controlling the strength and appearance of vertical surfaces. It defines the pattern and density of infill inside the print, determining internal strength while minimizing material use and print time.

Temperature settings form another critical category of information within profiles. The nozzle temperature must be specified for the material being used, as different plastics melt at different temperatures and even the same material from different manufacturers may require slight temperature adjustments. The heated bed temperature, if your printer has one, is similarly specified. Some profiles include separate temperatures for the initial layer versus subsequent layers, recognizing that the first layer often benefits from higher temperatures to improve adhesion to the build surface.

Print speed parameters define how quickly the print head moves during various operations. There isn’t just one print speed but rather a collection of speeds for different purposes. The profile specifies speeds for printing outer perimeters where quality matters most, inner perimeters where speed can be higher, infill where speed can be highest, and top and bottom solid layers that fall somewhere in between. Initial layer speeds are typically slower to ensure proper bed adhesion, while travel moves when the nozzle isn’t extruding can be quite fast since quality during these moves doesn’t matter.

Cooling settings determine how fans are used during the print. The profile specifies when cooling fans should activate, how fast they should spin at various points in the print, and whether cooling should vary based on layer time. Small, detailed layers benefit from more cooling to solidify the plastic quickly before the next layer is added, while large layers with plenty of time to cool naturally might need less fan speed. The balance of cooling affects layer adhesion, bridging performance, and overall print quality in complex ways that profiles help manage.

Support generation parameters tell the slicer when and how to create support structures. The profile defines the maximum overhang angle that can be printed without support, the density and pattern of support material, whether supports should be generated everywhere or only from the build plate, and how supports should attach to the model. For printers with dual extrusion capability, the profile specifies whether to use soluble support material and all the parameters governing that second material.

Retraction settings control how the printer pulls filament back when moving between areas to prevent oozing and stringing. The retraction distance and speed are specified, along with parameters for how retractions interact with other movements. Some profiles include wipe settings where the nozzle makes a small move while retracting to catch any oozing plastic. Z-hop settings, which lift the nozzle slightly during travel moves, can also be part of the profile.

Advanced parameters include things like acceleration and jerk settings that control how aggressively the printer changes speed and direction, combing modes that determine how travel moves are routed to avoid crossing open areas, and special handling for small features or thin walls. Some profiles include advanced features like linear advance values that compensate for pressure buildup in the nozzle, or adaptive layer heights that automatically vary based on model geometry.

The sheer volume of settings might seem overwhelming, and in fact, most slicing programs have dozens or even hundreds of adjustable parameters. The beauty of profiles is that you don’t need to understand or adjust every single parameter to get good results. You can start with a working profile and modify just the settings that matter most for your specific needs, leaving the rest at their proven values. As your understanding grows, you can refine more parameters, but profiles allow you to work at whatever level of complexity matches your current knowledge and requirements.

The Hierarchy of Profiles: Printer, Material, and Quality

Most modern slicing software organizes settings into a hierarchical structure with multiple types of profiles that work together. Understanding this hierarchy is essential for effectively managing your settings and knowing which profile to modify when you need to make changes. The three main categories are printer profiles, material profiles, and quality or print profiles, and they interact in specific ways to determine your final settings.

Printer profiles contain settings specific to your particular 3D printer hardware. These settings define the physical capabilities and characteristics of your machine. The profile includes the build volume dimensions, telling the slicer how large an object you can print and preventing you from trying to print something that won’t fit. It specifies whether your printer has a heated bed, how many extruders it has, and what kind of firmware it runs. The profile defines the printer’s mechanical resolution, the maximum speeds it can safely achieve, and any special features like auto bed leveling or filament runout detection that affect how the slicer generates instructions.

Printer profiles also include start and end G-code scripts, which are the commands executed at the beginning and end of every print. The start script typically includes commands to home the printer, heat up the nozzle and bed, prime the extruder to ensure plastic is flowing, and perform any other initialization needed. The end script includes commands to turn off heaters, retract filament, move the print head to a safe position, and disable motors. These scripts are intimately connected to your specific printer model and setup, which is why they live in the printer profile rather than in material or quality profiles.

Material profiles contain settings specific to different types of filament. Each material you use, whether it’s PLA, PETG, ABS, TPU, or any other plastic, has different properties and requires different handling. The material profile specifies the optimal nozzle and bed temperatures for that material. It defines cooling fan speeds, as some materials like PLA benefit from aggressive cooling while others like ABS need minimal cooling to prevent cracking. The material profile includes retraction settings that vary based on the material’s stringing tendency and viscosity.

Material profiles also specify the material’s density, which the slicer uses to calculate how much filament a print will consume and what it will weigh. They may include shrinkage factors that adjust dimensions to compensate for the material contracting as it cools. Some materials require special handling like enclosures to maintain ambient temperature, slower speeds to prevent issues, or specific build surface preparations, and these requirements can be captured in material profiles.

Quality or print profiles define the balance between speed, detail, and strength for a particular printing goal. These profiles contain settings like layer height, infill density and pattern, number of perimeters, and top and bottom layer counts. They specify print speeds for various operations, choosing faster speeds for draft-quality prints or slower speeds for high-detail work. The quality profile determines whether features like adaptive layer heights are enabled and sets thresholds for various quality-related decisions.

The hierarchy works by having these profiles layer on top of each other. You select a printer profile that defines your hardware, a material profile that defines what you’re printing with, and a quality profile that defines how you want to print. Settings in more specific profiles can override settings from more general profiles where appropriate. For example, while print speed is primarily determined by the quality profile, a particularly challenging material might specify maximum speeds in its material profile that override the quality profile’s speeds if they would be too fast for that material.

This hierarchical system provides tremendous flexibility. You can switch between materials by simply selecting a different material profile, and all the material-specific settings change while your quality preferences remain constant. You can switch between draft and high-quality printing by changing the quality profile without losing your material settings. If you upgrade or change printers, you select a different printer profile and your material and quality preferences transfer to the new hardware.

Most slicing programs come with predefined profiles for popular printers and common materials. These provide excellent starting points, but the real power comes from creating custom profiles tailored to your specific situation. You might create material profiles for each brand and color of PLA you regularly use, discovering that they print slightly differently and benefit from individualized settings. You might develop multiple quality profiles ranging from “ultra-fast draft” through “standard” to “maximum detail” to cover your typical printing needs. Understanding the profile hierarchy helps you know where to save these customizations for maximum flexibility and reusability.

Creating Your First Custom Profile: A Systematic Approach

Creating effective custom profiles might seem daunting at first, but following a systematic approach makes the process manageable and builds a solid foundation for continued refinement. The key is to start with a working baseline, make targeted adjustments, test thoroughly, and document what you learn along the way. This methodical process ensures that your custom profiles are genuinely improvements over defaults rather than collections of random changes that might introduce new problems.

Begin by selecting the most appropriate default profile as your starting point. If you’re printing PLA on a common printer like an Ender 3 or Prusa i3, there are likely well-developed default profiles available. Print a test object using this default profile and carefully evaluate the results. Use calibration prints like a calibration cube, temperature tower, or stringing test that help reveal specific aspects of print quality. Take notes about what works well and what could be improved. Is the surface quality acceptable? Are there stringing issues? Does the print match the intended dimensions? This baseline print gives you objective data to compare against as you make modifications.

Once you’ve established your baseline, identify the single most important aspect you want to improve. This focused approach is crucial because changing multiple settings simultaneously makes it difficult to understand what actually caused any improvement or regression in print quality. If surface quality is your primary concern, you might adjust print speeds or cooling settings. If dimensional accuracy needs work, you might modify extrusion multipliers or temperature. If print time is too long, you might increase speeds or layer height. Choose one area to address first.

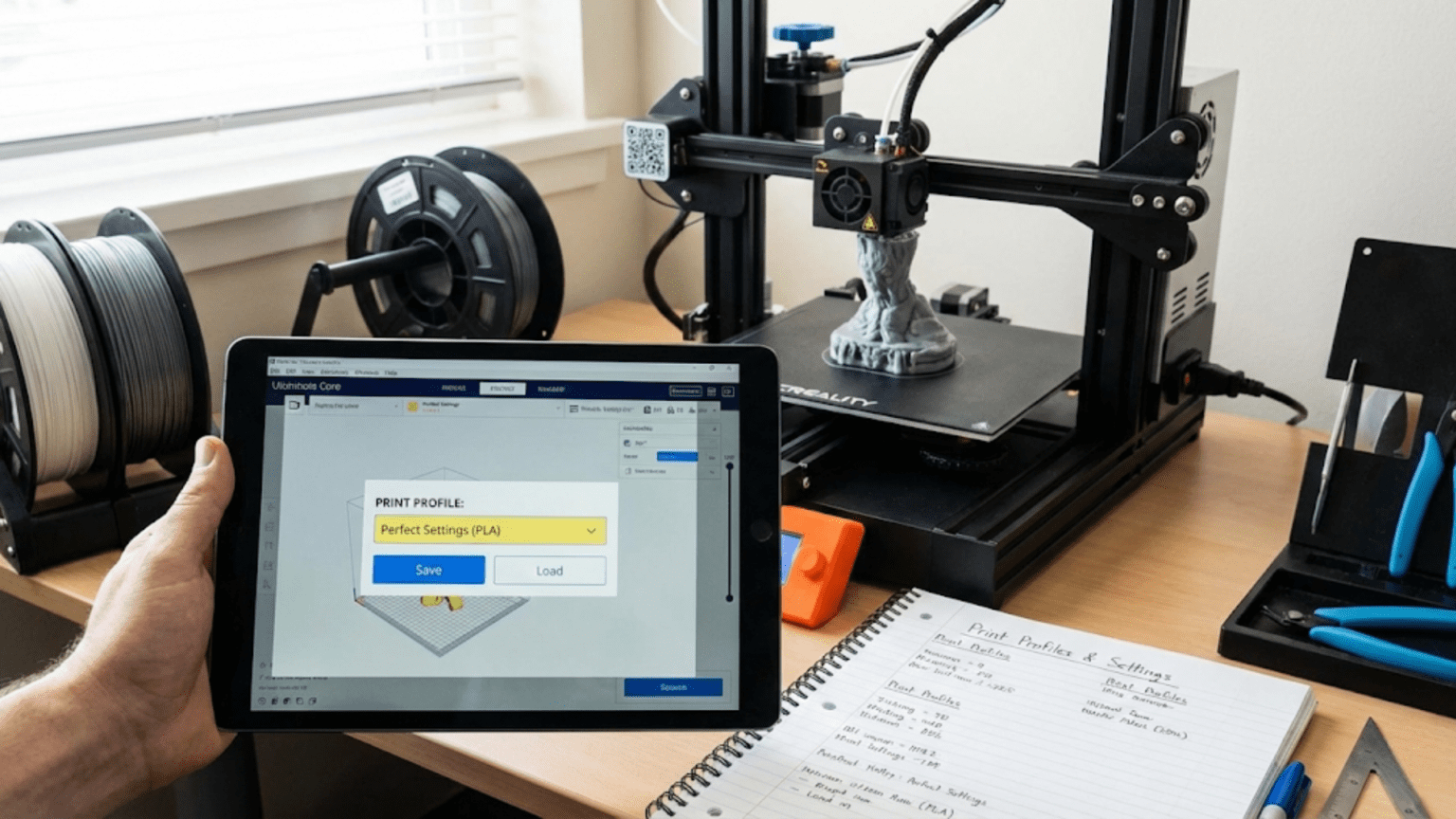

Make a small, deliberate change to the setting you’ve identified. Don’t make dramatic adjustments because subtle changes often have significant effects. If you’re adjusting temperature, try increasing or decreasing by just five degrees. If you’re modifying print speed, change it by ten or twenty percent rather than doubling or halving it. After making your change, save the profile with a descriptive name that indicates what you’ve modified. Something like “PLA – Standard – Slower Perimeters” helps you remember what makes this profile different from your baseline.

Print the same test object again with your modified profile. Compare the results carefully to your baseline print, looking specifically at the aspect you intended to improve. Did the change have the desired effect? Were there any unintended consequences in other areas? Sometimes fixing one issue can create or reveal another. For example, reducing print speed to improve surface quality might increase print time beyond what’s acceptable, or increasing temperature to improve layer adhesion might introduce stringing issues. These trade-offs are normal, and understanding them helps you find the right balance for your needs.

If the change improved things, consider whether further adjustment in the same direction would help more or if you’ve found the optimal setting. If the change made things worse or had no effect, revert to your previous value and try adjusting in the opposite direction or consider a different parameter. This iterative process gradually refines each setting until you’ve achieved a noticeable overall improvement. Some printers and materials respond more dramatically to certain settings than others, so you’re also learning about your specific equipment through this process.

Once you’ve optimized one parameter, move on to the next area for improvement. Work through your priority list systematically, always comparing against your baseline and previous iterations. Keep careful notes about what changes you made and what effects they had. Over time, you’ll develop an intuition for which settings address which issues, but initially, systematic documentation prevents you from forgetting what you’ve learned.

When you’ve achieved results that consistently meet your needs across multiple test prints, you have a solid custom profile. At this point, give it a clear, descriptive name and consider it your new baseline for that material and quality level. You might continue refining it over time as you gain more experience or as you encounter specific challenges, but you now have a reliable starting point that produces known-good results. Creating additional profiles for different materials or quality levels follows the same systematic process, building on the knowledge you’ve gained.

Organizing and Managing Your Profile Library

As you develop custom profiles for different materials, quality levels, printers, and applications, your profile library will grow. Without good organization, you can quickly find yourself confused about which profile to use or unable to locate the specific profile you need. Implementing a systematic approach to profile management from the beginning saves frustration and helps you build an increasingly valuable resource library.

Naming conventions are foundational to good profile organization. Develop a consistent naming scheme that clearly identifies what each profile is for and what makes it unique. A useful pattern includes the material type, the quality or purpose descriptor, and any specific characteristic that distinguishes it. Examples might be “PLA – Draft – Fast,” “PLA – Standard – Balanced,” “PETG – High Detail – Slow Perimeter,” or “TPU – Flexible – Low Retraction.” The names should be descriptive enough that you can identify the appropriate profile at a glance without having to open and examine its settings.

Some users include printer names in their profiles if they have multiple machines, such as “Ender3 – PLA – Standard” versus “Prusa – PLA – Standard.” This approach works well when the same material prints differently on different machines due to hardware differences. Others prefer to maintain separate profile libraries for each printer, keeping the printer identity separate from the profile names. Either approach can work as long as you’re consistent and the organization makes sense to you.

Consider creating a tiered set of profiles for each material you regularly use. A basic set might include a fast draft profile for rapid prototyping, a standard profile for everyday printing, and a high-quality profile for parts where appearance or precision matters most. Some users expand this to include specialized profiles like “Maximum Strength” with high infill and thick walls, “Miniature Detail” with fine layer heights and slow speeds, or “Large Print” with thick layers and robust settings designed to minimize the chance of failure during overnight prints.

Documentation within profiles helps you remember why settings are what they are. Most slicing programs allow you to add notes or descriptions to profiles. Use this feature to record important information like which brand of filament the profile was optimized for, what printer modifications it assumes, or what specific challenges it addresses. You might note something like “Optimized for Prusament PLA – Slower first layer for textured bed – Fan at 100% after layer 3.” These notes become invaluable when you return to a profile months later and need to remember its purpose or limitations.

Regular backups of your profile library protect against loss and enable sharing across computers or with colleagues. Most slicing programs store profiles in accessible folders on your computer, making it straightforward to back them up to cloud storage or an external drive. When you make significant improvements to a profile, creating a backup of the previous version before saving the new one provides a safety net if the changes don’t work out as expected. Some users maintain versioned profiles, keeping “PLA – Standard – v1,” “PLA – Standard – v2,” and so on, though this can lead to clutter if not carefully managed.

Periodic review and consolidation of your profile library prevents it from becoming unwieldy. As you gain experience, you may find that several similar profiles could be merged, or that some profiles you created for specific purposes are no longer needed. A yearly or bi-yearly review where you examine each profile, test whether it still produces good results, and consider whether it’s still useful helps keep your library manageable and relevant. Technology and materials evolve, and settings that were optimal a year ago might need updating based on new firmware, slicer versions, or material formulations.

Sharing profiles with the community or colleagues creates opportunities to learn from others’ experience. Many slicing programs include features for exporting and importing profiles, making it easy to share your successful configurations. Online communities often share profiles optimized for specific printers or materials, and trying these can provide new insights or serve as starting points for further customization. When sharing profiles, include clear documentation about what printer, modifications, materials, and conditions the profile was designed for to help others adapt it to their situations.

For users managing multiple printers or working in team environments, some advanced slicing programs offer profile synchronization features or centralized profile management. These capabilities ensure that everyone is using the same tested profiles and that improvements made by one person become available to the whole team. Even without specialized software, maintaining a shared folder with the team’s standard profiles and a simple version control system keeps everyone aligned and builds collective knowledge.

Material-Specific Profile Development: Beyond the Defaults

While default material profiles provide good starting points, developing material-specific profiles that account for the particular brands, colors, and batches of filament you actually use can significantly improve print reliability and quality. Different manufacturers formulate their materials with slightly different additives and processing methods, and even different colors from the same manufacturer can print differently due to pigment variations. Understanding how to develop and refine material-specific profiles addresses these real-world variations.

Start by understanding that the key parameters in material profiles are those directly related to the material’s physical properties and behavior during printing. Temperature is the most obvious and often the most impactful. While a material like PLA might have a general recommended temperature range of one hundred ninety to two hundred twenty degrees Celsius, your specific brand and color might print best at two hundred or two hundred five degrees. The optimal temperature balances several factors including flow consistency, layer adhesion, stringing tendency, and the ability to bridge gaps. Temperature towers, which print multiple sections at different temperatures in a single print, help you identify the sweet spot for each specific filament.

Cooling requirements vary significantly between materials and even between brands of the same material. Some PLA filaments print beautifully with maximum cooling, while others develop layer adhesion issues if cooled too aggressively. PETG typically requires moderate cooling, but the exact fan speed that produces the best balance of layer adhesion and bridging performance varies. ABS and other materials prone to warping need minimal cooling or none at all. When developing material profiles, print tests that include overhangs, bridges, and vertical surfaces to evaluate how different cooling settings affect various aspects of print quality.

Retraction settings are another critical area where material-specific tuning pays dividends. Some filaments are more prone to stringing than others due to differences in melt viscosity and formulation. A retraction distance that works perfectly for one brand of PETG might cause grinding with another brand or fail to eliminate stringing with a third. Retraction speed similarly needs adjustment for different materials. Start with conservative settings from a default profile and incrementally adjust based on stringing test results until you find the combination that minimizes stringing without causing extrusion problems.

The relationship between print speed and material behavior often requires material-specific adjustment. Some filaments handle fast printing well, maintaining consistent flow and good layer adhesion at high speeds. Others become unreliable when pushed too fast, developing under-extrusion, poor layer bonding, or visible artifacts. Engineering materials like nylon or polycarbonate often demand slower speeds than standard PLA to achieve good results. Your material profile should reflect realistic maximum speeds for that specific material based on testing rather than assuming all materials can handle the same speeds.

Flow rate or extrusion multiplier adjustments address the fact that not all filaments have exactly the advertised diameter or perfectly consistent diameter throughout the spool. A filament that’s slightly thinner than specification will under-extrude if you use default flow settings, while slightly thicker filament will over-extrude. Printing a single-wall calibration cube and measuring the wall thickness helps you determine if flow adjustment is needed. The material profile should include the flow calibration so that dimensional accuracy is consistent across all prints with that material.

Some materials benefit from special handling captured in material profiles. Flexible filaments like TPU or TPE require slower speeds, careful retraction settings or even disabled retraction, and sometimes adjusted acceleration to prevent buckling in the extruder. Specialty materials like wood-filled, metal-filled, or glow-in-the-dark filaments are abrasive and may require modified settings to account for increased wear on the nozzle. Composite materials with carbon fiber or glass fiber might need specific temperatures and flow adjustments. The material profile is the right place to capture these special requirements so they’re automatically applied whenever you select that material.

Bed adhesion requirements vary by material and should be reflected in material profiles. PLA typically adheres well to many surfaces with minimal preparation. PETG can stick too well and damage some bed surfaces, benefiting from a release agent. ABS requires higher bed temperatures and sometimes adhesion promoters like glue stick. Nylon is notoriously difficult to get to stick and might require specific temperatures, surfaces, or preparations. The material profile should specify bed temperature and can include notes about recommended bed preparation, though the actual bed surface setup is usually handled outside the slicer.

As you accumulate different brands and types of filament, maintaining detailed material profiles for each becomes increasingly valuable. You might have separate profiles for “Generic PLA,” “Prusament PLA,” “Hatchbox PLA,” and “eSun PLA+” if you find they print differently enough to warrant individual optimization. While this creates more profiles to manage, the reliability and quality improvements make the organization effort worthwhile. Each profile represents tested, proven settings that consistently produce good results with that specific material, eliminating guesswork and reducing failed prints.

Quality Profiles: Balancing Speed, Detail, and Strength

Quality profiles define the fundamental balance between competing priorities in 3D printing. The triangle of print speed, surface detail, and part strength represents the core trade-offs you navigate with every print decision. Understanding how to create quality profiles that intelligently balance these factors for different applications is essential for efficient, successful printing.

Layer height is the primary determinant of print speed and detail in quality profiles. Thicker layers mean fewer total layers to reach a given height, directly reducing print time. A twenty millimeter tall object printed at three hundred micron layer height requires about sixty-seven layers, while the same object at one hundred micron layers needs two hundred layers, roughly tripling the print time. However, thicker layers create more visible stepping on curved and angled surfaces and limit the finest details that can be reproduced. Your quality profiles should span this range, with a fast profile using thick layers like two hundred fifty or three hundred microns, a standard profile around one hundred fifty or two hundred microns, and a fine detail profile at one hundred microns or less.

Print speed settings in quality profiles work in concert with layer height to determine overall print time. You can’t just arbitrarily set very fast speeds because the printer has physical limits in how quickly it can melt and deposit material. Volumetric flow rate, measured in cubic millimeters per second, represents the actual limit. This is the product of layer height, line width, and print speed. If you increase layer height for a fast print, you may need to moderate print speeds to stay within your hotend’s maximum flow rate. Conversely, with fine layers, you can often print faster without hitting flow limits. Quality profiles should include tested speed settings that work reliably with their specified layer heights.

Infill density and pattern affect both print time and part strength. Higher infill takes longer to print but creates stronger parts. A fast draft profile might use fifteen or twenty percent infill since internal strength often isn’t critical for prototypes or test fits. A standard profile might use twenty to thirty percent infill providing reasonable strength for typical applications. A strength-focused profile could use fifty percent or even higher infill when maximum mechanical performance is required. The infill pattern also matters, with some patterns like gyroid providing better strength for a given density while others like grid print faster. Quality profiles can match pattern to purpose, using faster patterns for draft prints and stronger patterns for functional parts.

The number of perimeter walls significantly impacts both strength and print time. More walls create stronger parts with better surface quality but take longer to print. A fast profile might use just two perimeters, adequate for non-structural parts. A standard profile typically uses three or four perimeters. A strength-focused profile might use five or more perimeters, creating thick outer shells that dramatically increase part strength. The outermost perimeter is printed most slowly in all profiles to ensure the best surface quality since it’s the visible surface, but inner perimeters can be printed faster.

Top and bottom layer counts work similarly to perimeters. More solid layers on the top and bottom create smoother surfaces and seal the infill more completely but add print time. Fast profiles might use three or four top and bottom layers, while quality profiles might use five to seven layers or more. The appropriate count also depends on your infill pattern and density because some patterns need more solid layers to completely bridge over them. Quality profiles should include tested layer counts that reliably produce solid, closed surfaces without visible infill showing through.

Acceleration and jerk settings affect how aggressively the printer changes speed and direction, influencing both print quality and speed. More aggressive settings allow faster printing because the printer spends less time ramping up and down between moves. However, too-aggressive settings can cause ringing or ghosting artifacts where mechanical vibrations create ripples in the print surface. Fast profiles might use higher acceleration to maximize speed despite some quality compromise. Quality profiles would use more conservative acceleration settings to minimize artifacts. These settings interact with your printer’s mechanical characteristics, so they often benefit from per-printer tuning within quality profiles.

Special features can be enabled or disabled in quality profiles based on their impact on speed and quality. Adaptive layer height, which automatically varies layer height based on geometry, improves quality while moderating the speed penalty of fine layers. A quality profile might enable this feature while a fast draft profile keeps it disabled to simplify processing. Z-hop, which lifts the nozzle during travel moves to prevent collisions, improves reliability but adds time. Quality profiles concerned with consistency might enable it while fast profiles might leave it off. Combing, which routes travel moves through infill to avoid crossing perimeters, improves surface quality but lengthens travel paths. The profile’s priorities determine whether these features are worth their costs.

Creating a family of quality profiles spanning your typical use cases provides tremendous workflow efficiency. Instead of constantly adjusting individual settings, you simply select “Fast Draft” for quick test prints, “Standard” for everyday parts, “High Detail” for display models, or “Maximum Strength” for functional components. Over time, you refine each profile based on experience with various prints, and they become increasingly reliable tools that help you quickly achieve appropriate results for each application. The key is ensuring each profile has a clear purpose and represents a proven combination of settings that reliably delivers results matching that purpose.

Advanced Profile Techniques: Conditional Settings and Modifiers

As you become more comfortable with basic profile management, advanced techniques offer additional control and automation. These approaches use the more sophisticated features of modern slicing software to create profiles that automatically adapt to different situations or that apply special handling to specific regions of a print. Understanding these capabilities can significantly improve your efficiency and the quality of complex prints.

Per-feature speed control represents one powerful advanced technique. Instead of using the same speed for all perimeters or all infill, you can specify different speeds based on the feature type, size, or location. Most slicers allow separate speeds for external perimeters versus internal perimeters, recognizing that the visible outer wall benefits most from slow, careful printing while inner walls can be faster. You can specify different speeds for small perimeters versus large perimeters, slowing down for small, detailed features while maintaining speed on large, simple areas. Overhangs and bridges often have their own speed settings, printing more slowly to improve cooling and reduce sagging.

Layer time adjustments create another dimension of automatic adaptation. When a layer has very little material to deposit and would complete quickly, there may not be sufficient time for the plastic to cool before the next layer is added. This is particularly problematic with small, detailed features or tall, thin objects. Advanced profiles can include minimum layer time settings that automatically slow down the print or pause between layers to ensure adequate cooling time. The inverse is also possible, where very large layers with extended print times might reduce fan speed since the material has plenty of time to cool naturally. These automatic adjustments eliminate the need to manually intervene or create special profiles for different object sizes.

Variable layer height or adaptive layer height is a sophisticated technique where the profile includes rules for automatically varying layer height throughout a print based on geometry. Areas with significant curvature or fine detail use thinner layers to capture detail, while areas with simple, straight geometry use thicker layers for speed. The slicer analyzes the model and makes these decisions automatically based on parameters you specify in the profile. You might set a range like one hundred to two hundred microns and define how aggressively the slicer should vary layers based on geometric features. This creates prints with quality approaching fine-layer settings but time much closer to coarse-layer settings.

Modifiers or per-object settings allow you to override profile settings for specific regions of a print or specific objects when printing multiple items. You might place a modifier box around a small, detailed area of a model and specify that just that region prints with thinner layers or slower speeds. The rest of the model uses your standard profile settings, but the critical area gets special treatment automatically. This is incredibly powerful for parts that have both simple and complex regions, allowing you to optimize each area appropriately without creating entirely separate print jobs. Modifiers can adjust virtually any setting from temperatures to speeds to infill density, creating localized variations as needed.

Sequential printing settings allow printing multiple objects one at a time rather than layer-by-layer across all objects. This can be beneficial when printing multiple small items, as each completes before the next begins, allowing earlier items to be removed and reducing the impact of a mid-print failure. The profile must include clearance settings ensuring the print head can reach all areas of each object without colliding with previously completed objects. This technique requires careful consideration of part placement and printer geometry but can improve efficiency and reliability in production scenarios.

Print scheduling or priority settings in profiles can control the order in which features are printed within a layer. Some profiles might print inner walls before outer walls to allow any imperfections to be smoothed by the outer perimeter. Others might print outer walls first to prevent the nozzle from colliding with inner walls while printing the outer perimeter. Support structures can be scheduled relative to the model features, printed first to provide a clean surface for model features or printed last to minimize the chance of damage during printing. Understanding these ordering options and selecting appropriate settings for your applications improves print quality in subtle but important ways.

Temperature management can extend beyond simple settings to include advanced features like temperature towers built into profiles or automatic temperature variation during prints. Some materials benefit from different temperatures for initial layers versus bulk printing versus final layers. Profiles can specify these progressions. When printing materials prone to heat creep or clogging, gradually decreasing temperature through the print might help. When printing materials requiring annealing, ending with higher temperatures might improve final properties. These advanced thermal profiles require careful testing but can solve specific material challenges.

Support interface layers represent another advanced profile technique. Instead of having support material directly contact your model, which makes it difficult to remove and can damage surfaces, interface layers create thin sacrificial layers between supports and the model. The profile specifies how many interface layers, their density, and often uses different settings making them easier to remove while still providing adequate support. This results in better surface finish on supported areas and easier support removal. Profiles for materials commonly requiring supports benefit greatly from well-tuned interface settings.

Troubleshooting Profile Problems: When Settings Don’t Work

Even carefully developed profiles sometimes produce unexpected results, particularly when conditions change or when applying profiles to new models with different characteristics. Developing troubleshooting skills for profile-related problems helps you quickly identify and resolve issues rather than abandoning working profiles or creating unnecessary variations.

One common problem is discovering that a profile that worked perfectly for one model produces poor results on a different model. This often indicates that the profile’s settings are too narrowly optimized for specific geometric features or print sizes. For example, cooling settings that work well for a large print might be inadequate for a small print where each layer completes quickly. Speed settings appropriate for simple geometry might cause quality issues on intricate details. When a profile fails on a new model, first identify what’s different about the new model compared to where the profile worked. Is it much larger or smaller? Does it have more overhangs? More fine details? Thinner walls? Understanding what differs helps you identify which settings need adjustment.

Layer adhesion problems suggest temperature or cooling issues in your profile. If layers are separating or the print is weak, the material isn’t bonding properly between layers. First verify that temperatures are appropriate for your specific material, as batches can vary. Try increasing the nozzle temperature by five or ten degrees in the material profile. If your print profile includes aggressive cooling, particularly for materials like ABS or ASA that are sensitive to rapid temperature changes, reducing fan speeds might improve adhesion. For PLA having adhesion issues, the opposite might be true, the material might be overheating and benefit from more cooling. Testing with single-variable changes helps identify the right adjustment.

Dimensional accuracy problems where prints are consistently too large or too small indicate flow or temperature issues. If prints are consistently oversized by a small amount all around, you’re likely over-extruding and should reduce the flow rate or extrusion multiplier in your material profile. If prints are undersized, you’re under-extruding and should increase flow. However, if dimensions are correct in XY but wrong in Z, you might have layer height problems or temperature issues affecting layer squish. If specific features like holes are consistently wrong while overall dimensions are correct, you might need to adjust horizontal expansion or hole compensation settings in your printer profile.

Stringing or oozing problems indicate retraction or temperature issues in material profiles. Excessive stringing suggests either temperature is too high, retraction isn’t aggressive enough, or travel speeds are too slow allowing time for oozing. Try reducing temperature first as this often has the biggest impact. If that doesn’t solve it, increase retraction distance or speed. Verify that travel moves are happening at full speed. If you’ve already got aggressive retraction settings and still see stringing, the filament itself might be problematic and need different settings than similar materials. Some filaments string more readily than others, and your material profile needs to account for this.

Inconsistent extrusion or visible variations in line width suggest either flow rate problems or speed-related issues. If some areas of the print look overextruded while others look underextruded, pressure advance or linear advance features might need calibration. These settings in your printer or material profile compensate for lag in pressure buildup in the nozzle. Visible ringing or ghosting from corners spreading across surfaces indicates acceleration or speed settings in your quality profile are too aggressive for your printer’s mechanical capabilities. Reducing speed or acceleration eliminates these artifacts.

First layer adhesion failures could stem from bed leveling issues rather than profile problems, but if leveling is correct, check bed and nozzle temperatures in your material profile. First layer settings often differ from subsequent layers, and these might need adjustment. Some profiles include separate first layer temperatures and speeds. If the first layer isn’t squishing adequately, the nozzle might be too far from the bed, but profile-wise, the first layer height setting might be too large. A first layer around one hundred twenty percent of your regular layer height usually works well, giving good squish without over-compression.

Support removal difficulties or poor surface finish where supports contacted the model suggest support settings in your print profile need refinement. Increasing support-to-model gap distance makes supports easier to remove but might compromise support effectiveness. Support interface layers create a buffer zone that improves surface finish at support contacts. Adjusting support density makes them easier to remove but potentially less stable. Finding the right balance requires testing, but once established, documenting these settings in your profile prevents future issues.

When profile problems persist despite adjustments, sometimes starting fresh with a known-good default profile provides better results than continuing to modify a problematic custom profile. Over-modification can introduce subtle interactions between settings that create hard-to-diagnose issues. Periodically reverting to defaults and rebuilding custom profiles from that clean baseline can reveal if you’ve drifted into problematic territory with accumulated changes. This is why maintaining good documentation of what makes your custom profiles different from defaults helps you rebuild efficiently when needed.

Profile Optimization for Specific Applications

Different applications for 3D printing have different priorities that should be reflected in specialized profiles. Understanding how to optimize profiles for specific use cases helps you build a toolkit of reliable profiles covering your most common printing scenarios. Rather than constantly adjusting settings, you can select the appropriate application-specific profile and trust that it represents tested, proven settings for that purpose.

Prototyping profiles prioritize speed and material efficiency while maintaining enough quality to evaluate form, fit, and function. These profiles typically use coarse layer heights around two hundred fifty to three hundred microns, low infill around fifteen to twenty percent, and just two or three perimeters. Print speeds are aggressive, taking advantage of the coarse layers to minimize time. Support settings favor easy removal over surface quality since prototype surfaces will likely be iterated anyway. The goal is getting test pieces in hand as quickly as possible to evaluate designs and make decisions. These profiles might sacrifice surface finish and dimensional precision for raw speed.

Mechanical parts profiles emphasize strength and dimensional accuracy. These use medium layer heights around one hundred fifty to two hundred microns for a good balance of strength and reasonable print time. Infill density increases to thirty to forty percent or higher, with strong patterns like gyroid or honeycomb. Perimeter counts increase to four or more, creating thick walls that resist stress. Top and bottom layers are generous, fully sealing the interior structure. Temperatures might be slightly higher to ensure excellent layer bonding. Print speeds moderate to maintain dimensional accuracy since parts need to fit together properly. These profiles might include specific adjustments for threads, snap fits, or other mechanical features.

Display model profiles prioritize surface quality and detail over speed or strength. Fine layer heights from fifty to one hundred microns capture surface detail and minimize visible layer lines. Perimeter speeds slow significantly on outer walls to ensure the smoothest possible finish. Cooling settings optimize for surface appearance, often using high fan speeds for PLA to freeze layers quickly and create crisp details. Infill might be relatively low since strength doesn’t matter, or patterns might be chosen for how they’re visible if the model is partially transparent. These profiles accept long print times as necessary for achieving exhibition-quality results.

Miniature and figure profiles represent an extreme of detail-focused printing. Layer heights drop to twenty-five to fifty microns to capture fine features and smooth curves on small objects. Nozzle sizes might be reduced to two tenths of a millimeter for finest detail. Speeds slow dramatically because the features being printed are so small. Cooling runs at maximum to solidify each tiny layer before the next is added. Support settings use dense interfaces and careful placement to preserve surface quality. These profiles can result in extraordinarily long print times, but the detail achieved makes this acceptable for display-quality miniatures.

Flexible material profiles address the specific challenges of printing TPU, TPE, and other elastomers. Speeds reduce dramatically, often to ten or fifteen millimeters per second, because these materials buckle in the extruder if pushed too fast. Retraction often disables entirely or uses minimal distance because flexible materials don’t respond well to retraction. Cooling settings vary by specific material but generally remain moderate. Infill patterns avoid crossing paths that create strings, using rectilinear patterns instead. Flow rates might need adjustment because these materials compress differently than rigid plastics. The profile essentially addresses the unique behavior of flexible materials.

Large format printing profiles optimize for reliability during long prints of big objects. Layer heights increase to two hundred to three hundred microns to make large prints feasible in reasonable time frames. Nozzle sizes might increase to six tenths or eight tenths of a millimeter for faster material deposition. Infill uses patterns and densities providing strength without excessive material consumption. Perimeter counts balance strength and print time. Critical settings like bed adhesion receive extra attention because failures on large prints waste significant time and material. These profiles might enable additional safety features like babystep Z adjustment or filament sensors to catch problems before they ruin hours of printing.

Specialty application profiles address specific use cases like food-safe items requiring particular materials and settings, outdoor parts needing UV-resistant materials and solid construction, or electrical enclosures needing specific materials and design considerations. Each specialty application may warrant a dedicated profile capturing all the requirements specific to that use case. Building this library of application-specific profiles represents accumulated knowledge and testing that makes future similar projects much more efficient.

Sharing and Collaborating: Profile Management in Teams and Communities

The knowledge embedded in well-developed print profiles has value beyond individual use. Sharing profiles within teams, communities, or the broader 3D printing world helps others avoid repeating the same troubleshooting and optimization you’ve already done. Understanding how to effectively share profiles and benefit from others’ shared profiles enhances everyone’s printing experience and accelerates the learning curve for newcomers.

Most slicing software includes export and import functions for profiles, typically saving them as configuration files or packages that bundle multiple related profiles together. When preparing to share a profile, first ensure it’s thoroughly tested and produces consistent results. Document clearly what printer model, firmware version, and any modifications the profile assumes. Specify what material brand and type it’s optimized for, as material variations mean profiles don’t always transfer perfectly between different filaments even of the same generic type. Include notes about any special preparation or conditions the profile requires, like specific bed surfaces, enclosure requirements, or ambient temperature considerations.

Creating comprehensive documentation separate from the profile file itself helps recipients understand when and how to use shared profiles. A simple readme file accompanying the profile might include printer specifications, recommended materials with specific brands, expected print quality level, known limitations, and examples of prints produced with the profile. If you’ve made specific optimizations for certain geometry types or applications, note this so others know if the profile suits their needs. Screenshots of key settings or slicer configuration screens can help recipients verify they’ve imported the profile correctly.

Version control becomes important when sharing profiles that continue to evolve. Consider including version numbers or dates in profile names, and maintain a changelog documenting what changed in each version. This helps users understand whether they should update to a newer version and what improvements or changes to expect. If you discover a problem with a widely-shared profile, clearly communicate the issue and provide an updated version promptly to prevent others from experiencing the same problem.

Online communities and forums dedicated to specific printers or slicing software often have profile repositories where users share their configurations. These can be excellent resources for finding starting points when working with new materials or printers. However, approach shared profiles with some caution. Test them thoroughly on non-critical prints before relying on them for important work. Even well-intentioned profiles might include settings that work well for the original creator’s setup but not for yours due to differences in printer calibration, material batch, environmental conditions, or modifications. Consider shared profiles as recommended starting points rather than definitive solutions.

Team environments benefit greatly from standardized profile libraries that ensure consistent results across multiple printers and operators. In a makerspace, educational setting, or production environment, maintaining a curated set of tested profiles that everyone uses prevents the confusion of dozens of individual variations and ensures that results are predictable regardless of who’s running the print. One person or a small team should be responsible for testing and approving profiles before they’re added to the standard library, ensuring quality control.

Collaboration tools and processes around profile development can include shared folders with version-controlled profiles, documentation wikis explaining profile purposes and settings, testing protocols that new profiles must pass before approval, and feedback mechanisms where users report problems or suggest improvements. Regular review meetings to discuss profile performance, address issues, and incorporate improvements keep the profile library evolving based on collective experience. This systematic approach to profile management transforms profiles from individual preferences into institutional knowledge.

Contributing to manufacturer and community profile development represents another aspect of collaboration. Many popular printers and slicers rely on community-contributed profiles for less common materials or printer configurations. If you develop particularly good profiles for niche applications, contributing them back helps future users and strengthens the community. Most open-source slicing software has processes for submitting profile contributions, often through GitHub or similar collaboration platforms.

When adopting profiles from others, take time to understand what makes them different from defaults rather than just applying them blindly. Examine key settings and compare to your current profiles. Try to understand why certain choices were made. This analysis helps you learn more about the relationships between settings and results, building your own expertise. You might discover approaches you hadn’t considered or identify settings that work particularly well and can be incorporated into your own profiles. Profiles shared by others aren’t just time-savers; they’re learning opportunities.

The Future of Print Profiles: Automation and Intelligence

As 3D printing technology matures and slicing software becomes more sophisticated, the future of print profiles is likely to include more automation, intelligence, and adaptive capabilities that reduce the manual effort currently required for optimization. Understanding emerging trends helps you anticipate future capabilities and appreciate how current profile management skills will remain relevant even as tools evolve.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are beginning to influence slicer development, with the potential to dramatically change how profiles work. An AI-assisted slicer might analyze a model’s geometry and automatically select or generate optimal settings rather than requiring the user to choose from predefined profiles. The system could recognize that one region needs support, another requires fine detail settings, and a third can print quickly with coarse settings, all automatically adjusted. Early implementations of this technology are appearing in some slicing software, and as datasets of successful prints grow, these systems will become increasingly capable.

Automatic calibration procedures are evolving to require less manual intervention. Instead of printing temperature towers and manually evaluating results, future slicers might include closed-loop testing where the printer prints test patterns, uses cameras or sensors to evaluate results, and automatically adjusts settings for optimal outcomes. This automatic calibration could extend to material profiles, printer profiles, and quality profiles, significantly reducing the expertise and time required to achieve good results. The resulting automatically-optimized profiles would still be saved and reused, but their creation would be far more accessible to beginners.

Cloud-based profile libraries represent another emerging trend. Instead of profiles being stored locally on individual computers, they could live in cloud repositories with intelligent search and recommendation systems. You might describe what you’re trying to print and what material you’re using, and the system recommends profiles that have produced successful results for similar situations. User ratings and feedback could help identify the most reliable profiles. Updates and improvements to profiles could propagate automatically to all users. This cloud-based approach would make the collective knowledge of the entire 3D printing community more accessible.

Material identification systems using RFID tags or barcode scanning could automatically select appropriate material profiles when you load a new spool. Instead of manually selecting “PETG – Red” from your profile library, the printer reads the spool’s identifier and automatically loads the correct profile. If you haven’t used that specific material before, the system might download an appropriate profile from a cloud repository or generate one based on similar materials. This automation reduces errors and makes the printing process more foolproof.

Environmental sensing and compensation represents another frontier. Future printers might include humidity and temperature sensors that automatically adjust profile settings to compensate for environmental variations. A material that prints perfectly at twenty degrees Celsius and forty percent humidity might need different settings at thirty degrees and seventy percent humidity. Rather than requiring the user to create separate profiles for different environmental conditions or manually adjust settings, the system would compensate automatically based on current conditions.

Continuous feedback during printing could enable real-time profile adjustment. Cameras monitoring print quality might detect that layer adhesion is marginal and automatically increase temperature or reduce cooling mid-print. Sensors detecting dimensional accuracy issues might adjust flow rates as needed. This would represent a shift from static profiles that define all settings before printing begins to dynamic profiles that serve as starting points but adapt during the print based on observed performance. The successful adaptations would be captured and used to update the base profile for future prints.

Integration with design software could enable profile suggestions during the modeling phase. As you design a part in CAD software, the system might analyze the geometry and suggest appropriate print profiles, or highlight features that will be challenging to print with your available profiles, encouraging design changes to improve manufacturability. This tight integration between design and manufacturing would make 3D printing more accessible and reduce failed prints due to incompatibilities between design and printing capabilities.

Despite these advancing automation capabilities, the fundamental understanding of what profiles contain and how settings interact will remain valuable. Automated systems work best when guided by users who understand the principles behind the settings. When automatic systems produce unexpected results or when working with unusual materials or applications outside the system’s training data, the ability to manually adjust profiles and understand what those adjustments accomplish will continue to be important. The skills you develop in manual profile creation and optimization translate directly into the ability to guide, troubleshoot, and extend automated systems.

Conclusion: Profiles as a Foundation for Printing Success

Print profiles represent far more than simple convenience features in slicing software. They embody the accumulated knowledge and experience you gain as you develop your 3D printing skills, capturing tested, proven combinations of settings that reliably produce desired results. Understanding profiles, how to create them, how to organize them, and how to optimize them for specific applications transforms 3D printing from an unpredictable craft where each print is an experiment into a reliable manufacturing process where results are consistent and predictable.

The journey from using only default profiles to developing comprehensive custom profile libraries mirrors the journey from beginner to experienced 3D printing practitioner. Early on, default profiles provide working starting points that allow you to focus on basic printer operation and understanding fundamental concepts. As you encounter situations where defaults fall short, you begin making adjustments and learning how specific settings affect results. Creating your first custom profiles captures this learning and ensures you can replicate successful outcomes. Over time, your profile library expands to cover the full range of materials, quality levels, printers, and applications you regularly encounter.

The discipline of systematic profile development, careful testing, thorough documentation, and methodical organization pays long-term dividends. Each well-developed profile represents hours of experimentation and refinement that you never have to repeat. When facing a new printing challenge, you start from proven profiles that work rather than from scratch. Your profile library becomes a personal knowledge base documenting what works for your specific equipment, materials, and requirements. This accumulated knowledge makes you progressively more efficient and capable over time.

The collaborative aspects of profile sharing and community resources extend your capabilities beyond your personal experience. Learning from others’ profiles, contributing your own successful configurations, and participating in the collective refinement of printing knowledge benefits everyone in the community. The open-source ethos that characterizes much of the 3D printing world applies to profile development as much as to printer hardware and software. Everyone building on everyone else’s work accelerates progress and makes the technology more accessible.

Looking forward, the increasing sophistication of automation and artificial intelligence in slicing software will make many aspects of profile management easier, particularly for common scenarios and standard materials. However, the fundamental understanding of what profiles contain, how settings interact, and how to optimize for specific requirements will remain valuable. Automated systems work best when they can be guided by users who understand the underlying principles, and unusual situations will always require manual intervention from knowledgeable operators.

Your investment in learning about print profiles, developing systematic approaches to creating and managing them, and building comprehensive profile libraries pays dividends every time you print. Instead of treating each print as a new challenge requiring setting adjustments, you select the appropriate profile and trust that the result will meet your expectations based on previous successes. This reliability transforms 3D printing from a sometimes-frustrating hobby or experimental tool into a practical manufacturing method you can depend on. The confidence that comes from having proven profiles for every common situation you encounter enables you to focus on design, application, and results rather than getting bogged down in troubleshooting and adjustment.

Ultimately, mastering print profiles means mastering the translation between what you want to create and how your equipment can best create it. Profiles are the bridge between intent and execution, between design and physical reality. They capture not just settings but understanding, not just numbers but knowledge gained through experience. Every successful profile in your library represents a solved problem, a conquered challenge, a lesson learned and recorded for future benefit. Building and maintaining this library is one of the most valuable activities you can engage in as you develop your 3D printing capabilities.